Ill Chapter Five OUTER SPACE FANTASY I: SHIKASTA and THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Narrative in Doris Lessing's and J.M. Coetzee's Life Writings

Identity and narrative in Doris Lessing's and J.M. Coetzee's Life Writings ENG-3992 Shkurte Krasniqi Master’s Thesis in English Literature Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education University of Tromsø Spring 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Gerd Karin Bjørhovde for her constructive criticism and for encouraging me to work on this thesis. She is an inspiration to me. I would also like to thank my family for supporting me from afar: you are always on my mind. Last but not least, I am grateful to have my husband Jørn by my side. Abstract The main focus of this thesis is the manner in which Doris Lessing and J.M Coetzee construct their identities in their life writings. While Lessing has written a “classical” autobiography using the first person and past tense, Coetzee has opted for a more fictional version using the third person and the present tense. These different approaches offer us a unique opportunity to look into the manner in which fiction and facts can be combined and used to create works of art which linger permanently between the two. It is also interesting to see how these two writers have dealt with the complications of being raised in Southern Africa and how that influences their social and personal identities. In the Introduction I present the writers and their oeuvres briefly. In Chapter 1, I explain the terms connected with life writing, identity and narrative. In the second chapter I begin by looking into the manner in which their respective life writings begin and what repercussions does using the first and the third person have? In the third chapter I analyse their relational identities, i.e. -

Shikasta: Re, Colonised Planet 5 (Vintage International) by Doris Lessing

Shikasta: Re, Colonised Planet 5 (Vintage International) by Doris Lessing Ebook Shikasta: Re, Colonised Planet 5 (Vintage International) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Shikasta: Re, Colonised Planet 5 (Vintage International) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Vintage International+++Paperback:::: 384 pages+++Publisher:::: Vintage; 1st Vintage Books ed edition (August 12, 1981)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0394749774+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0394749778+++Product Dimensions::::5.2 x 0.9 x 8 inches++++++ ISBN10 0394749774 ISBN13 978-0394749 Download here >> Description: This is the first volume in the series of novels Doris Lessing calls collectively Canopus in Argos: Archives. Presented as a compilation of documents, reports, letters, speeches and journal entries, this purports to be a general study of the planet Shikasta–clearly the planet Earth–to be used by history students of the higher planet Canopus and to be stored in the Canopian archives. For eons, galactic empires have struggled against one another, and Shikasta is one of the main battlegrounds.Johar, an emissary from Canopus and the primary contributor to the archives, visits Shikasta over the millennia from the time of the giants and the biblical great flood up to the present. With every visit he tries to distract Shikastans from the evil influences of the planet Shammat but notes with dismay the ever-growing chaos and destruction of Shikasta as its people hurl themselves towards World War III and annihilation. The Nobel Prize winning author Doris Lessing wrote a series of novels that are illuminating insights based on the idea that we here on planet Earth are but one of hundreds of planetary colonies. -

“A Small Voice for the Earth” – a Romantic and Green Reading of Doris Lessing's Shikasta

“A Small Voice for the Earth” – A Romantic and Green Reading of Doris Lessing’s Shikasta Riikka Siltaoja University of Tampere School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies English Philology Master’s Thesis December 2012 Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö SILTAOJA, RIIKKA: Ekokriittinen ja romanttinen luenta Doris Lessingin romaanista Shikasta Pro gradu-tutkielma, 73 sivua Syksy 2012 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Tutkielmassani tarkastelen Doris Lessingin science fiction-romaania Shikasta (1979) ekokriittisestä näkökulmasta. Pyrin myös osoittamaan sen yhteyden romanttisen luontokirjallisuuden ja pastoraalin perinteeseen. Doris Lessing on tullut tunnetuksi erityisesti vasemmistolaisena kirjailijana, mutta hän on myös tunnettu siitä, miten vaikea hänen töitään on kategorioida. Väitän tutkielmassani, että Shikastassa on havaittavissa paitsi Lessingin pettymys kommunismiin ja puoluepolitiikkaan, myös selkeä filosofinen siirtymä ’punaisesta vihreään’ politiikkaan. Ensin tarkastelen Shikastan sosialistisia piirteitä pohjautuen Terry Eagletonin etiikkaan teoksessa After Theory (2003), erityisesti suhteessa hänen käsitykseensä objektiivisuudesta ja Aristoteelisesta hyveestä, jotka ovat hänen moraalikäsityksensä perustana. Esitän, että Shikastan esittämä yhteiskuntamalli sekä moraalikäsitys ovat ideologialtaan utopistisen sosialistisia. Ne pohjautuvat erityisesti kollektiiviselle rakkaudelle, -

Engaging Macrohistory Through the Present Moment

ARTICLE .3 Engaging Macrohistory through the Present Moment Anthony Judge Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potential Belgium Introduction The question explored here is how the text of macrohistory – and its larger dynamic – gets written It is distinctly presumptuous for a non-historian to into the individual psychic fabric. Can it exist otherwise? comment on issues of macrohistory that are the focus of extensive studies1 – or is it? Is it appropriate to frame macrohistory as only being a matter for historians? As Identifying Longer-term Rhythms with war and other matters, is macrohistory too impor- 2 There has long been a preoccupation with the tant to be left to historians? longer-term rhythms of human existence that only The following is therefore a reflection on the signif- much more recently came to provide a context for icance of the rhythms of macrohistory for lived experi- macrohistory – but were notably neglected despite the ence in the present moment – an experience that is a work of Pitrim Sorokin (Social and Cultural Dynamics feature of the lived reality of all. The question is how do, 1937). Much is made of the capacity of the earliest or could, people engage with macrohistory – without observers to explore astronomical cycles and predict being historians? Responding to the details of macrohis- eclipses – in both cases judged as being determining tory over centuries is naturally disempowering to many. factors in the cycles of society and human experience. It might well be expected to engender a sense of apathy This provided a basis for astrology that remains vitally -- despite the sense of perspective some claim it offers. -

136 Chapter Six OUTER SPACE FANTASY II: the SIRIAN EXPERIMENTS, the MAKING of the REPRESENTATIVE for PLANET 8 and the SENTIMENTA

136 Chapter Six OUTER SPACE FANTASY II: THE SIRIAN EXPERIMENTS, THE MAKING OF THE REPRESENTATIVE FOR PLANET 8 AND THE SENTIMENTAL AGENTS OF THE VOLYEN EMPIRE Nettled by expressions of dissatisfaction after the publication of Shikasta and Marriages, Leasing explains her purpose once again in a preface to the third novel in this series, The Sirian Experiments (1981) . In sum, Lessing invites readers to see the series "as a framework that enables me to tell (I hope) a beguiling tale or two; to put questions both to myself and to others; to explore ideas and sociological possibilities" (1981:12). Lessing, certainly does this in the next three novels of the series—The Sirian Experiments (1981), The Making of the Representative for Planet 8 (1983) ,_and The Sentimental Agents of the Volven Empire (1983). THE SIRIAN EXPERIMENTS The reviewers find ii\any faults with Lessing's The Sirian Experiments. For instance, Edwin Morgan says that the book "is not as well written as it might be. Misplaced particles abound. Singulars and plurals are confounded, sentences are made verbless quite unnecessarily and there is too much reliance on those magic dots..." (TLS, 1981:431). They find her ideas "too near the 137 surface, too little assimilated" (Wilce, 1981:24) but do not explain which ideas they mean, and hastily conclude that the book is "not good science fiction or good Lessing. Fanatics only " (Niccol, 1981:72). However, Robert Alter's review is a perceptive and interesting one. He considers the Canopus in Arqos series to belong to what Northrop Frye called an "anatomy"; that is, "a combination of fantasy and morality" (NYTBR, 1981:1) which "presents a vision of the world in terms of a single intellectual pattern" (NYTBR, 1981:24). -

Canopus in Argos: Archives : “Outer” Space Science Fiction Exploring the “Inner” Space Travel Through Eastern Concept of “Planes of Existence”

CANOPUS IN ARGOS: ARCHIVES : “OUTER” SPACE SCIENCE FICTION EXPLORING THE “INNER” SPACE TRAVEL THROUGH EASTERN CONCEPT OF “PLANES OF EXISTENCE” SUMAN CHAUDHARY Research Scholar MGS University Bikaner (Rajasthan) (INDIA) Doris Lessing, a self-proclaimed space science fiction author through a dry, archival format of her five-novel science fiction series, Canopus in Argos: Archives interrogates metaphorical “inner” spiritual space into the cosmic “outer” space. The paper attempts at delineation of this attainment of spiritual advancement of soul through drawing parallels between author’s Cosmological planes with the “Planes of Existence” in Eastern philosophy. Lessing’s Cosmological planes are the real Zones with their physical boundaries, their own government, their weather, and rules. The paper represents that each Zone in Lessing’s world is at certain spiritual level that corresponds to a plane of existence in Esoteric philosophy, and Hindu occultism. The age-old insularities of the Zones are finally broken into achievement of spiritual growth of their inhabitant’s inner soul, and final communion with the “One” or “Brahaman”. Key Words – Planes of Existence, Lokas in Hinduism, Cosmological Zones Introduction Science fiction authors have been delving into the areas of “outer” space from times immemorial, but the 2007 Nobel Prize winner, Doris Lessing has been attempting to fathom the “inner” space metaphor too. Canopus in Argos: Archives is truly a remarkable series of the science fiction genre, with its narrative style too matching the dry, archival and report format of a physicist. Lessing is an unbiased teacher, and thus mentions in the Preface to her opening novel of the series, Shikasta: “The sacred literatures of all races and nations have many things in common. -

Accelerating Evolution of Species in Doris Lessing Canopus in Argos : a Critique

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) ACCELERATING EVOLUTION OF SPECIES IN DORIS LESSING CANOPUS IN ARGOS : A CRITIQUE Dr. D. N. Ganjewar Associate Professor, Research Guide & Head Department of English Arts, Comm. & Science College Kille Dharur Dist. Beed [M.S.] Abstract The present research paper is a critique of Doris Lessing’s Canopus in Argos as a sequence of novels in search of the evolution being aided by advanced species for less advanced species and societies. The novels take place in the same future history. The novels give a detailed picture of requisition of scientific evolution from the beginning to the contemporary status of the species. It no doubt provides the origin and evolution of humanity and their consequences. Thus, the paper applies to the history and its causes for the evolution of species in the world. It is the first part of the Critique as regards the first three sequence novels of Doris Lessing in Canopus in Argos. Keywords: Doris Lessing, Evolution, species, origin of humanity. Doris Lessing is a distinguished Nobel Prize in Literature-winning novelist. Her novel, Canopus in Argos is a sequence of five science fiction books. Their major thrust is to depict a number of societies at different stages of development, over a great period of time. The focus here is no doubt on accelerated evolution being aided by advanced species for less advanced species and societies. The novels take place in the same future history. Each novel covers unrelated events, with the exception of Shikasta and The Sirian Experiments. -

Doris Lessing At

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS Shikasta presents a revised version of Earth in the titular planet. Reports written by colonial servants of the galactic empire Canopus, historical texts, accounts and case studies create a diffuse narrative. There are echoes of Southern Rhodesia, where white settlers had seeded themselves at the end of the nineteenth century: Lessing described it as “a very nasty little police state”. For instance, native people on Rohanda (a col ony that reappears in the more sociological BILD VIA GETTY SCHIFFER-FUCHS/ULLSTEIN third book, The Sirian Experiments) are subjected to “an allout booster, TopLevel Priority, ForcedGrowth Plan”, an explicit imperialist project. The second book, The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five, set in ‘zones’ of civilization circling Shikasta, is an intense and explosive explo ration of gender dynamics and stereotypical interactions between men and women. In The Making of the Representative for Planet 8, Lessing examines human behaviour in the face of a brutal ice age. The inhabitants of Planet 8 must ultimately accept climate based extinction, aided by a Canopean Doris Lessing, photographed in 1990. official, Doeg. This mythic apocalyptic par able was influenced by Anna Kavan’s 1967 FICTION scifi novel Ice, as well as the death of British explorer Robert Falcon Scott in Antarctica in 1912, which fascinated Lessing. Towards the end, echoing current perceptions of plane Doris Lessing at 100: tary fragility, an inhabitant notes that “what we were seeing now with our new eyes was that all the planet had become a fine frail web roving time and space or lattice, with the spaces held there between the patterns of the atoms”. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9218972 The path of love: Sufism in the novels of Doris Lessing Galin, Muge N., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

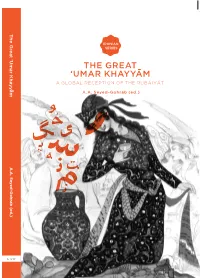

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Fictions of Time and Space: from Realism to Utopia in Doris Lessing's the Four-Gated City.'

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Society and Culture 2021-06-01 'Fictions of Time and Space: From Realism to Utopia in Doris Lessing's The Four-Gated City.' Sergeant, DRC http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/13113 10.1215/0041462X-9084315 Twentieth-Century Literature Duke University Press All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. FICTIONS OF TIME AND SPACE: FROM REALISM TO UTOPIA IN DORIS LESSING’S THE FOUR-GATED CITY Doris Lessing’s most famous work remains The Golden Notebook (1962). Partly this is the legacy of its reception as a feminist landmark – a legacy not diminished by Lessing’s own scepticism about such a reading. Partly, however, it is because The Golden Notebook constitutes a marker in twentieth-century fiction, as a writer previously known for her commitment to realism seemed to depart into more experimental modes; a fact not diminished – possibly, even, enhanced – by the nature of this departure being so unclear. As Tonya Krouse has described, a recognition of the novel’s experimentalism was ‘forestall[ed]’ (115) by Lessing’s 1971 Preface, which belatedly positioned it as a continuation of the work of Tolstoy and Stendhal; while critics such as Nick Bentley and Alice Ridout have continued to emphasise the novel’s engagement with that legacy. -

Spiritual Intuition in Lessing's Shikasta

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 4, Issue 10, October 2014 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Paradise Regained: Spiritual Intuition in Lessing’s Shikasta Hossein Shamshiri Department of English Literature, The University of Guilan, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The Noble Prize winning Doris Lessing created a flurry of discussion about her relevance to spiritualism, mysticism, and Sufism after her turn from realism to speculative fiction. It is the purpose of this study to show that Lessing’s proclivity for portraying imagined worlds in her later speculative space fiction reflects a paradigm shift that sheds light on the contemporary apocalyptic climate of clashing moral certainties. In her space fiction novels, the most important of which is Shikasta, Lessing, like a prophet, captured a zeitgeist and unveiled the wounds of our time. By analyzing the narrative techniques that Lessing uses in Shikasta I try to prove that Shikasta is central in Lessing’s prolific oeuvre because it so clearly sets forth the basic terms of her debate about universal identity and the way that it can be represented through fiction. My main discussion is that Lessing’s epistemology and ontology can be embodied in her belief in the Utopian future of the earth; the narrative structure of Shikasta shows that such a Utopia or Paradise can be regained by practicing the spiritual practices of Sufism. Index Terms: Mysticism, Narrative Technique, Collective Identity, Prophet, Utopia 1. Introduction Take warning from the misfortunes of others, so that others need not have to take warning from your own. - Saadi, Rose Garden1 Doris Lessing won the noble prize in literature in 2007; the year that marked the 800th birthday of Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi2 (1207-1273).