Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IBM Z Systems Introduction May 2017

IBM z Systems Introduction May 2017 IBM z13s and IBM z13 Frequently Asked Questions Worldwide ZSQ03076-USEN-15 Table of Contents z13s Hardware .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 z13 Hardware ........................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Performance ............................................................................................................................................................................ 19 z13 Warranty ............................................................................................................................................................................ 23 Hardware Management Console (HMC) ..................................................................................................................... 24 Power requirements (including High Voltage DC Power option) ..................................................................... 28 Overhead Cabling and Power ..........................................................................................................................................30 z13 Water cooling option .................................................................................................................................................... 31 Secure Service Container ................................................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 1: Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.6 – 1.7: Performance and Power

Chapter 1: Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.6 – 1.7: Performance and power ITSC 3181 Introduction to Computer Architecture https://passlaB.githuB.io/ITSC3181/ Department of Computer Science Yonghong Yan [email protected] https://passlab.github.io/yanyh/ Lectures for Chapter 1 and C Basics Computer Abstractions and Technology • Lecture 01: Chapter 1 – 1.1 – 1.4: Introduction, great ideas, Moore’s law, aBstraction, computer components, and program execution • Lecture 02: C Basics; Memory and Binary Systems • Lecture 03: Number System, Compilation, Assembly, Linking and Program Execution ☛• Lecture 04: Chapter 1 – 1.6 – 1.7: Performance, power and technology trends • Lecture 05: – 1.8 - 1.9: Multiprocessing and Benchmarking 2 § 1.6 Performance 1.6 Defining Performance • Which airplane has the best performance? Boeing 777 Boeing 777 Boeing 747 Boeing 747 BAC/Sud BAC/Sud Concorde Concorde Douglas Douglas DC- DC-8-50 8-50 0 100 200 300 400 500 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 Passenger Capacity Cruising Range (miles) Boeing 777 Boeing 777 Boeing 747 Boeing 747 BAC/Sud BAC/Sud Concorde Concorde Douglas Douglas DC- DC-8-50 8-50 0 500 1000 1500 0 100000 200000 300000 400000 Cruising Speed (mph) Passengers x mph 3 Response Time and Throughput • Response time çè Latency – How long it takes to do a task • Throughput çè Bandwidth – Total work done per unit time • e.g., tasks/transactions/… per hour • How are response time and throughput affected by – Replacing the processor with a faster version? – Adding more processors? • We’ll focus on response time for now… 4 Relative Performance • Define Performance = 1/Execution Time • “X is n time faster than Y”, i.e. -

Computer Organization and Architecture Designing for Performance Ninth Edition

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION AND ARCHITECTURE DESIGNING FOR PERFORMANCE NINTH EDITION William Stallings Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Editorial Director: Marcia Horton Designer: Bruce Kenselaar Executive Editor: Tracy Dunkelberger Manager, Visual Research: Karen Sanatar Associate Editor: Carole Snyder Manager, Rights and Permissions: Mike Joyce Director of Marketing: Patrice Jones Text Permission Coordinator: Jen Roach Marketing Manager: Yez Alayan Cover Art: Charles Bowman/Robert Harding Marketing Coordinator: Kathryn Ferranti Lead Media Project Manager: Daniel Sandin Marketing Assistant: Emma Snider Full-Service Project Management: Shiny Rajesh/ Director of Production: Vince O’Brien Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Managing Editor: Jeff Holcomb Composition: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Production Project Manager: Kayla Smith-Tarbox Printer/Binder: Edward Brothers Production Editor: Pat Brown Cover Printer: Lehigh-Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Manufacturing Buyer: Pat Brown Text Font: Times Ten-Roman Creative Director: Jayne Conte Credits: Figure 2.14: reprinted with permission from The Computer Language Company, Inc. Figure 17.10: Buyya, Rajkumar, High-Performance Cluster Computing: Architectures and Systems, Vol I, 1st edition, ©1999. Reprinted and Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Figure 17.11: Reprinted with permission from Ethernet Alliance. Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on the appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2013, 2010, 2006 by Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. -

Examining the Viability of FPGA Supercomputing

1 Examining the Viability of FPGA Supercomputing Stephen D. Craven and Peter Athanas Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 USA email: {scraven,athanas}@vt.edu Abstract—For certain applications, custom computational hardware created using field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) produces significant performance improvements over processors, leading some in academia and industry to call for the inclusion of FPGAs in supercomputing clusters. This paper presents a comparative analysis of FPGAs and traditional processors, focusing on floating- point performance and procurement costs, revealing economic hurdles in the adoption of FPGAs for general High-Performance Computing (HPC). Index Terms— computational accelerator, digital arithmetic, Field programmable gate arrays, high- performance computing, supercomputers. I. INTRODUCTION Supercomputers have experienced a recent resurgence, fueled by government research dollars and the development of low-cost supercomputing clusters. Unlike the Massively Parallel Processor (MPP) designs found in Cray and CDC machines of the 70s and 80s, featuring proprietary processor architectures, many modern supercomputing clusters are constructed from commodity PC processors, significantly reducing procurement costs. In an effort to improve performance, several companies offer machines that place one or more FPGAs in each node of the cluster. Configurable logic devices, of which FPGAs are one example, permit the device’s hardware to be programmed multiple times after manufacture. A wide body of research over two decades has repeatedly demonstrated significant performance improvements for certain classes of applications when implemented within an FPGA’s configurable logic [1]. Applications well suited to speed-up by FPGAs typically exhibit massive parallelism and small integer or fixed-point data types. -

Trends in Electrical Efficiency in Computer Performance

ASSESSING TRENDS IN THE ELECTRICAL EFFICIENCY OF COMPUTATION OVER TIME Jonathan G. Koomey*, Stephen Berard†, Marla Sanchez††, Henry Wong** * Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Stanford University †Microsoft Corporation ††Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory **Intel Corporation Contact: [email protected], http://www.koomey.com Final report to Microsoft Corporation and Intel Corporation Submitted to IEEE Annals of the History of Computing: August 5, 2009 Released on the web: August 17, 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Information technology (IT) has captured the popular imagination, in part because of the tangible benefits IT brings, but also because the underlying technological trends proceed at easily measurable, remarkably predictable, and unusually rapid rates. The number of transistors on a chip has doubled more or less every two years for decades, a trend that is popularly (but often imprecisely) encapsulated as “Moore’s law”. This article explores the relationship between the performance of computers and the electricity needed to deliver that performance. As shown in Figure ES-1, computations per kWh grew about as fast as performance for desktop computers starting in 1981, doubling every 1.5 years, a pace of change in computational efficiency comparable to that from 1946 to the present. Computations per kWh grew even more rapidly during the vacuum tube computing era and during the transition from tubes to transistors but more slowly during the era of discrete transistors. As expected, the transition from tubes to transistors shows a large jump in computations per kWh. In 1985, the physicist Richard Feynman identified a factor of one hundred billion (1011) possible theoretical improvement in the electricity used per computation. -

Computer Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking

Computer Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking EE 382M Dr. Lizy Kurian John Evolution of Single-Chip Microprocessors 1970’s 1980’s 1990’s 2010s Transistor Count 10K- 100K-1M 1M-100M 100M- 100K 10 B Clock Frequency 0.2- 2-20MHz 20M- 0.1- 2MHz 1GHz 4GHz Instruction/Cycle < 0.1 0.1-0.9 0.9- 2.0 1-100 MIPS/MFLOPS < 0.2 0.2-20 20-2,000 100- 10,000 Hot Chips 2014 (August 2014) AMD KAVERI HOT CHIPS 2014 AMD KAVERI HOTCHIPS 2014 Hotchips 2014 Hotchips 2014 - NVIDIA Power Density in Microprocessors 10000 Sun’s Surface 1000 Rocket Nozzle ) 2 Nuclear Reactor 100 Core 2 8086 10 Hot Plate 8008 Pentium® Power Density (W/cm 8085 4004 386 Processors 286 486 8080 1 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Source: Intel Why Performance Evaluation? • For better Processor Designs • For better Code on Existing Designs • For better Compilers • For better OS and Runtimes Design Analysis Lord Kelvin “To measure is to know.” "If you can not measure it, you can not improve it.“ "I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely in your thoughts advanced to the state of Science, whatever the matter may be." [PLA, vol. 1, "Electrical Units of Measurement", 1883-05-03] Designs evolve based on Analysis • Good designs are impossible without good analysis • Workload Analysis • Processor Analysis Design Analysis Performance Evaluation -

Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks

9 Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks Kaivalya M. Dixit IBM Corporation “The reputation of current benchmarketing claims regarding system performance is on par with the promises made by politicians during elections.” Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC) was founded in October, 1988, by Apollo, Hewlett-Packard,MIPS Computer Systems and SUN Microsystems in cooperation with E. E. Times. SPEC is a nonprofit consortium of 22 major computer vendors whose common goals are “to provide the industry with a realistic yardstick to measure the performance of advanced computer systems” and to educate consumers about the performance of vendors’ products. SPEC creates, maintains, distributes, and endorses a standardized set of application-oriented programs to be used as benchmarks. 489 490 CHAPTER 9 Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks 9.1 Historical Perspective Traditional benchmarks have failed to characterize the system performance of modern computer systems. Some of those benchmarks measure component-level performance, and some of the measurements are routinely published as system performance. Historically, vendors have characterized the performances of their systems in a variety of confusing metrics. In part, the confusion is due to a lack of credible performance information, agreement, and leadership among competing vendors. Many vendors characterize system performance in millions of instructions per second (MIPS) and millions of floating-point operations per second (MFLOPS). All instructions, however, are not equal. Since CISC machine instructions usually accomplish a lot more than those of RISC machines, comparing the instructions of a CISC machine and a RISC machine is similar to comparing Latin and Greek. 9.1.1 Simple CPU Benchmarks Truth in benchmarking is an oxymoron because vendors use benchmarks for marketing purposes. -

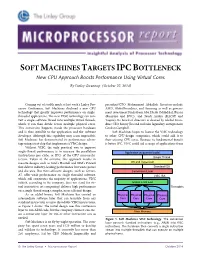

Soft Machines Targets Ipcbottleneck

SOFT MACHINES TARGETS IPC BOTTLENECK New CPU Approach Boosts Performance Using Virtual Cores By Linley Gwennap (October 27, 2014) ................................................................................................................... Coming out of stealth mode at last week’s Linley Pro- president/CTO Mohammad Abdallah. Investors include cessor Conference, Soft Machines disclosed a new CPU AMD, GlobalFoundries, and Samsung as well as govern- technology that greatly improves performance on single- ment investment funds from Abu Dhabi (Mubdala), Russia threaded applications. The new VISC technology can con- (Rusnano and RVC), and Saudi Arabia (KACST and vert a single software thread into multiple virtual threads, Taqnia). Its board of directors is chaired by Global Foun- which it can then divide across multiple physical cores. dries CEO Sanjay Jha and includes legendary entrepreneur This conversion happens inside the processor hardware Gordon Campbell. and is thus invisible to the application and the software Soft Machines hopes to license the VISC technology developer. Although this capability may seem impossible, to other CPU-design companies, which could add it to Soft Machines has demonstrated its performance advan- their existing CPU cores. Because its fundamental benefit tage using a test chip that implements a VISC design. is better IPC, VISC could aid a range of applications from Without VISC, the only practical way to improve single-thread performance is to increase the parallelism Application (sequential code) (instructions per cycle, or IPC) of the CPU microarchi- Single Thread tecture. Taken to the extreme, this approach results in massive designs such as Intel’s Haswell and IBM’s Power8 OS and Hypervisor that deliver industry-leading performance but waste power Standard ISA and die area. -

Performance Scalability of N-Tier Application in Virtualized Cloud Environments: Two Case Studies in Vertical and Horizontal Scaling

PERFORMANCE SCALABILITY OF N-TIER APPLICATION IN VIRTUALIZED CLOUD ENVIRONMENTS: TWO CASE STUDIES IN VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL SCALING A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Junhee Park In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 Copyright c 2016 by Junhee Park PERFORMANCE SCALABILITY OF N-TIER APPLICATION IN VIRTUALIZED CLOUD ENVIRONMENTS: TWO CASE STUDIES IN VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL SCALING Approved by: Professor Dr. Calton Pu, Advisor Professor Dr. Shamkant B. Navathe School of Computer Science School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Professor Dr. Ling Liu Professor Dr. Edward R. Omiecinski School of Computer Science School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Professor Dr. Qingyang Wang Date Approved: December 11, 2015 School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Louisiana State University To my parents, my wife, and my daughter ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My Ph.D. journey was a precious roller-coaster ride that uniquely accelerated my personal growth. I am extremely grateful to anyone who has supported and walked down this path with me. I want to apologize in advance in case I miss anyone. First and foremost, I am extremely thankful and lucky to work with my advisor, Dr. Calton Pu who guided me throughout my Masters and Ph.D. programs. He first gave me the opportunity to start work in research environment when I was a fresh Master student and gave me an admission to one of the best computer science Ph.D. -

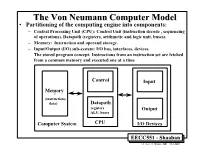

Clock Rate Improves Roughly Proportional to Improvement in L • Number of Transistors Improves Proportional to L2 (Or Faster)

TheThe VonVon NeumannNeumann ComputerComputer ModelModel • Partitioning of the computing engine into components: – Central Processing Unit (CPU): Control Unit (instruction decode , sequencing of operations), Datapath (registers, arithmetic and logic unit, buses). – Memory: Instruction and operand storage. – Input/Output (I/O) sub-system: I/O bus, interfaces, devices. – The stored program concept: Instructions from an instruction set are fetched from a common memory and executed one at a time Control Input Memory - (instructions, data) Datapath registers Output ALU, buses Computer System CPU I/O Devices EECC551 - Shaaban #1 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 Generic CPU Machine Instruction Execution Steps Instruction Obtain instruction from program storage Fetch Instruction Determine required actions and instruction size Decode Operand Locate and obtain operand data Fetch Execute Compute result value or status Result Deposit results in storage for later use Store Next Determine successor or next instruction Instruction EECC551 - Shaaban #2 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 HardwareHardware ComponentsComponents ofof AnyAny ComputerComputer Five classic components of all computers: 1. Control Unit; 2. Datapath; 3. Memory; 4. Input; 5. Output } Processor Computer Keyboard, Mouse, etc. Processor Memory Devices (active) (passive) Control Input (where Unit programs, data Disk Datapath live when Output running) Display, Printer, etc. EECC551 - Shaaban #3 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 CPUCPU OrganizationOrganization • Datapath Design: – Capabilities & performance characteristics of principal Functional Units (FUs): • (e.g., Registers, ALU, Shifters, Logic Units, ...) – Ways in which these components are interconnected (buses connections, multiplexors, etc.). – How information flows between components. • Control Unit Design: – Logic and means by which such information flow is controlled. – Control and coordination of FUs operation to realize the targeted Instruction Set Architecture to be implemented (can either be implemented using a finite state machine or a microprogram). -

An Algorithmic Theory of Caches by Sridhar Ramachandran

An algorithmic theory of caches by Sridhar Ramachandran Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY. December 1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1999. All rights reserved. Author Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Jan 31, 1999 Certified by / -f Charles E. Leiserson Professor of Computer Science and Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Arthur C. Smith Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students MSSACHUSVTS INSTITUT OF TECHNOLOGY MAR 0 4 2000 LIBRARIES 2 An algorithmic theory of caches by Sridhar Ramachandran Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineeringand Computer Science on Jan 31, 1999 in partialfulfillment of the requirementsfor the degree of Master of Science. Abstract The ideal-cache model, an extension of the RAM model, evaluates the referential locality exhibited by algorithms. The ideal-cache model is characterized by two parameters-the cache size Z, and line length L. As suggested by its name, the ideal-cache model practices automatic, optimal, omniscient replacement algorithm. The performance of an algorithm on the ideal-cache model consists of two measures-the RAM running time, called work complexity, and the number of misses on the ideal cache, called cache complexity. This thesis proposes the ideal-cache model as a "bridging" model for caches in the sense proposed by Valiant [49]. A bridging model for caches serves two purposes. It can be viewed as a hardware "ideal" that influences cache design. On the other hand, it can be used as a powerful tool to design cache-efficient algorithms. -

Atmega165p Datasheet

Features • High Performance, Low Power Atmel® AVR® 8-Bit Microcontroller • Advanced RISC Architecture – 130 Powerful Instructions – Most Single Clock Cycle Execution – 32 × 8 General Purpose Working Registers – Fully Static Operation – Up to 16 MIPS Throughput at 16 MHz – On-Chip 2-cycle Multiplier • High Endurance Non-volatile Memory segments – 16 Kbytes of In-System Self-programmable Flash program memory – 512 Bytes EEPROM – 1 Kbytes Internal SRAM 8-bit – Write/Erase cyles: 10,000 Flash/100,000 EEPROM(1)(3) – Data retention: 20 years at 85°C/100 years at 25°C(2)(3) Microcontroller – Optional Boot Code Section with Independent Lock Bits In-System Programming by On-chip Boot Program with 16K Bytes True Read-While-Write Operation – Programming Lock for Software Security In-System • JTAG (IEEE std. 1149.1 compliant) Interface – Boundary-scan Capabilities According to the JTAG Standard Programmable – Extensive On-chip Debug Support – Programming of Flash, EEPROM, Fuses, and Lock Bits through the JTAG Interface Flash • Peripheral Features – Two 8-bit Timer/Counters with Separate Prescaler and Compare Mode – One 16-bit Timer/Counter with Separate Prescaler, Compare Mode, and Capture Mode – Real Time Counter with Separate Oscillator –Four PWM Channels ATmega165P – 8-channel, 10-bit ADC – Programmable Serial USART ATmega165PV – Master/Slave SPI Serial Interface – Universal Serial Interface with Start Condition Detector – Programmable Watchdog Timer with Separate On-chip Oscillator – On-chip Analog Comparator Preliminary – Interrupt and Wake-up