The Dawn Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wall Free Climb in the World by Tommy Caldwell

FREE PASSAGE Finding the path of least resistance means climbing the hardest big- wall free climb in the world By Tommy Caldwell Obsession is like an illness. At first you don't realize anything is happening. But then the pain grows in your gut, like something is shredding your insides. Suddenly, the only thing that matters is beating it. You’ll do whatever it takes; spend all of your time, money and energy trying to overcome. Over months, even years, the obsession eats away at you. Then one day you look in the mirror, see the sunken cheeks and protruding ribs, and realize the toll taken. My obsession is a 3,000-foot chunk of granite, El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. As a teenager, I was first lured to El Cap because I could drive my van right up to the base of North America’s grandest wall and start climbing. I grew up a clumsy kid with bad hand-eye coordination, yet here on El Cap I felt as though I had stumbled into a world where I thrived. Being up on those steep walls demanded the right amount of climbing skill, pain tolerance and sheer bull-headedness that came naturally to me. For the last decade El Cap has beaten the crap out of me, yet I return to scour its monstrous walls to find the tiniest holds that will just barely go free. So far I have dedicated a third of my life to free climbing these soaring cracks and razor-sharp crimpers. Getting to the top is no longer important. -

Seattle the Potential for More Depth and Richness Than Any Other Culture I Can Think Of

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG ANNUAL REPORT SPECIAL EDITION SPRING 2016 • VOLUME 110 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE The Doug Walker I Knew PAGE 12 Your Go-To Adventure Buddy PAGE 16 Leading the Way - Annual Report PAGES 19 - 40 Rescue on Dome Peak PAGE 41 2 mountaineer » spring 2016 tableofcontents Spring 2016 » Volume 110 » Number 2 Annual Report The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy 19 Leading the Way the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. The Mountaineers Annual Report 2015 Features 12 The Doug Walker I knew a special tribute by Glenn Nelson 16 Your Go-To Adventure Buddy an interview with Andre Gougisha 41 Rescue on Dome Peak Everett Mountaineers save the day 16 Columns 6 PEAK FITNESS reducing knee pain 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Tom Vogl 8 OUTDOOR EDUCATION from camper to pioneer 10 SAFETY FIRST VHF radios and sea kayaking 14 CONSERVATION CURRENTS our four conservation priorities 46 RETRO REWIND Wolf Bauer - a wonderful life 50 BRANCHING OUT your guide to the seven branches 52 GO GUIDE activities and courses listing 60 OFF BELAY 41 celebrating lives of cherished members 63 LAST WORD explore by Steve Scher Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates as Discover The Mountaineers a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various nonprofit If you're thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where organizations. to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of Mountaineer uses: informational meetings at each of our seven branches. -

{PDF} the Push a Climbers Journey of Endurance, Risk, and Going Beyond Limits 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

THE PUSH A CLIMBERS JOURNEY OF ENDURANCE, RISK, AND GOING BEYOND LIMITS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tommy Caldwell | 9780399562709 | | | | | The Push A Climbers Journey of Endurance, Risk, and Going Beyond Limits 1st edition PDF Book Caldwell emerged from these hardships with a renewed sense of purpose and determination. Jul 13, Wendy Gilbert rated it it was amazing. As his heart beats next to mine, my own doubles in size. Read more Read less. Alex Honnold. Children's Books. A New York Times Bestseller A dramatic, inspiring memoir by legendary rock climber Tommy Caldwell, the first person to free climb the Dawn Wall of Yosemite's El Capitan "The rarest of adventure reads: it thrills with colorful details of courage and perseverance but it enriches readers with an absolutely captivating glimpse into how a simple yet unwavering resolve can turn a A New York Times Bestseller A dramatic, inspiring memoir by legendary rock climber Tommy Caldwell, the first person to free climb the Dawn Wall of Yosemite's El Capitan "The rarest of adventure reads: it thrills with colorful details of courage and perseverance but it enriches readers with an absolutely captivating glimpse into how a simple yet unwavering resolve can turn adversity into reward. Caldwell is a fascinating guy. This engrossing memoir chronicles the journey of a boy with a fanatical mountain- guide father who was determined to instill toughness in his son to a teen whose obsessive nature drove him to the top of the sport-climbing circuit. I finished the book in less than two days, excited, cried, inspired, cried again, and now, i am more determined to train! Fiction Books. -

ALP 48 Caldwell.Pdf

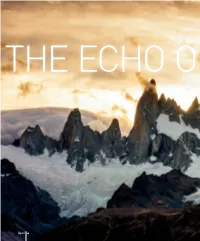

THE ECHO OF THE WIND 84 THE ECHO OF THE WIND TOMMY CALDWELL PHOTOS BY AUSTIN SIADAK “I DON’T KNOW ABOUT THIS,” I SAY. HUGE BLOBS OF RIME CLING TO THE WALL ABOVE. A WATERFALL RUNS OUT FROM A HOLE IN THE MOUNTAIN THAT RESEMBLES THE MOUTH OF A DRAGON. ICICLES GLISTEN LIKE GIANT TEETH. THE AIR IS STILL, BUT IN MY MIND, THE MEMORY OF THE WIND ROARS LIKE A DIN OF INHUMAN VOICES AND A RATTLE OF ICE AND STONES. 85 I look down at Alex Honnold for reassurance. get there,” Topher said, “we’re going to have to go His back has stiffened; his eyebrows are slightly straight into the mountains and start climbing.” furrowed. “Dude, you got this,” he says. “You’re a He was already dressed in his ratty synthetic pants total boss.” What have I gotten us into? I wonder. and a polypro shirt. I forced my eyelids shut. I Just three days ago, we were walking down the woke up when the rattling stopped. newly paved streets of El Chaltén, our footsteps From a distance, the peaks were hard to com- quick with anticipation. Alex had never been to prehend. Tumbling glaciers and jagged shapes Patagonia before. made a strange contrast to the desert plains that To the west, the evening sky washes in pale surrounded them. We dragged our duffel bags past purple. Far below, the shadow of the Fitz Roy a few scattered buildings. As plumes of dust blew massif stretches across the eastern plains: steep, in, we pulled our collars over our noses. -

Rock Climbing Fundamentals Has Been Crafted Exclusively For

Disclaimer Rock climbing is an inherently dangerous activity; severe injury or death can occur. The content in this eBook is not a substitute to learning from a professional. Moja Outdoors, Inc. and Pacific Edge Climbing Gym may not be held responsible for any injury or death that might occur upon reading this material. Copyright © 2016 Moja Outdoors, Inc. You are free to share this PDF. Unless credited otherwise, photographs are property of Michael Lim. Other images are from online sources that allow for commercial use with attribution provided. 2 About Words: Sander DiAngelis Images: Michael Lim, @murkytimes This copy of Rock Climbing Fundamentals has been crafted exclusively for: Pacific Edge Climbing Gym Santa Cruz, California 3 Table of Contents 1. A Brief History of Climbing 2. Styles of Climbing 3. An Overview of Climbing Gear 4. Introduction to Common Climbing Holds 5. Basic Technique for New Climbers 6. Belaying Fundamentals 7. Climbing Grades, Explained 8. General Tips and Advice for New Climbers 9. Your Responsibility as a Climber 10.A Simplified Climbing Glossary 11.Useful Bonus Materials More topics at mojagear.com/content 4 Michael Lim 5 A Brief History of Climbing Prior to the evolution of modern rock climbing, the most daring ambitions revolved around peak-bagging in alpine terrain. The concept of climbing a rock face, not necessarily reaching the top of the mountain, was a foreign concept that seemed trivial by comparison. However, by the late 1800s, rock climbing began to evolve into its very own sport. There are 3 areas credited as the birthplace of rock climbing: 1. -

Lofoten Climbs

1 Lofoten Climbs The West The Chris Craggs and Thorbjørn Enevold Henningsvær Rock Climbing on Lofoten and Stetind in Arctic Norway Kalle Text and route information by Chris Craggs and Thorbjørn Enevold All uncredited photos by Chris Craggs Other photography as credited Kabelvåg Edited by Alan James Technical Editor Stephen Horne Printed in Europe on behalf of LF Book Services (ISO 14001 and EMAS certified printers) Distributed by Cordee (cordee.co.uk) Svolvær All maps by ROCKFAX Some maps based on original source data from openstreetmap.org Published by Rockfax in May 2017 © ROCKFAX 2017, 2008 rockfax.com NortheastThe All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library. This book belongs to: Stetind This book is printed on FSC certified paper made from 100% virgin fibre sourced from sustainable forestry ISBN 978 1 873341 23 0 Cover - Mike Brumbaugh on the slanting corner of Vestpillaren Direct (N6) - page 175 - on Presten. Photo: Andrew Burr Walking Peaks Walking This page: Johan Hvenmark on Himmelen kan vente (N6+) - page 179 - on Presten. Photo: Jonas Paulsson Contents Lofoten Climbs 3 Lofoten Climbs Introduction ... 4 The West ...............68 The Rockfax App ............ 8 Vinstad................72 Symbol, Map and Topo Key.... 9 Helvetestinden ..........73 A Brief History ............. 10 Stamprevtinden .........79 Nord Norsk Klatreskole . 22 Merraflestinden .........80 Advertiser Directory......... 24 Breiflogtinden...........82 West The Acknowledgments .......... 26 Branntuva .............85 Lofoten Logistics .......... -

Reel Rock Press Release

It’s been a big year in climbing – from Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s epic saga on the Dawn Wall to the tragic loss of Dean Potter, one of the sport’s all-time greats. In our 10th year, the REEL ROCK Film Tour will celebrate them all with an incredible lineup of films that go beyond the headlines to stories that are both intimate and awe-inspiring. REEL ROCK 10 FILM LINEUP A LINE ACROSS the SKY 35 mins The Fitz Roy traverse is one of the most sought after achievements in modern alpinism: a gnarly journey across seven jagged summits and 13,000 vertical feet of climbing. Who knew it could be so much fun? Join Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold on the inspiring – and at times hilarious – quest that earned the Piolet d’Or, mountaineering’s highest prize. HIGH and MIGHTY 20 mins High ball bouldering – where a fall could lead to serious injury – is not for the faint of heart. Add to the equation a level of difficulty at climbing’s cutting edge, and things can get downright out of control. Follow Daniel Woods’ epic battle to conquer fear and climb the high ball test piece The Process. SHOWDOWN at HORSESHOE HELL 20 mins 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell is the wildest event in the climbing world; a mash-up of ultramarathon and Burning Man where elite climbers and gumbies alike go for broke in a sun-up to sun-down orgy of lactic acid and beer. But all fun aside, the competition is real: Can the team of Nik Berry and Mason Earle stand up Clockwise from top left: Alex Honnold at 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell; adventure sport icon Dean Potter; against the all-powerful Alex Honnold? Kevin Jorgeson on the Dawn Wall in Yosemite; Tommy Caldwell on the Dawn Wall in Yosemite DEAN POTTER TRIBUTE DAWN WALL: FIRST LOOK 6 mins 15 mins Dean Potter was the most iconic vertical adventurer of a Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s epic final push to free climb generation. -

The American Alpine Club Guidebook to Membership Alpinist Magazine

THE AMERICAN ALPINE CLUB GUIDEBOOK TO MEMBERSHIP ALPINIST MAGAZINE ith each print edition of Alpinist, we aim to create a work of art, paying attention to every detail— from our extended photo captions to our carefully Wselected images and well-crafted stories. Inside our pages, we strive to offer our readers an experience like that of exploratory climbing, a realm of words and images where they can wander, discover surprising new viewpoints, and encounter moments of excitement, humor, awe and beauty. By publishing the work of climbers from a wide range of ages, technical abilities, nations and cultures—united by their passion for adventure and wild places—we hope to reflect and enhance the sense of community within the climbing life. Over time, back issues have become collectors’ items, serving as historical references and ongoing inspirations. Like our readers, we believe that great writing and art about climbing demand the same boldness, commitment and vision as the pursuit itself. JOIN US. Exclusive AAC Member Pricing 1 Year - $29.95 | 2 Years - $54.95 Alpinist.com/AAC ALPINIST IS A PROUD PARTNER OF THE AMERICAN ALPINE CLUB Stay Connected! @AlpinistMag @Alpinist @AlpinistMag ALP_2019_AAC Ad FIN.indd 1 6/26/19 4:14 PM WELCOME, ALL 5 You Belong Here ARTIST SPOTLIGHT 8 Brooklyn Bell on Art for the In-betweens MEMBERSHIP THROUGH THE LENS 10 Inspiration, Delivered Directly NAVAJO RISING 23 An Indigenous Emergence Story WHEN WOMEN LEAD 27 Single Pitch Instructors for the 21st Century GLACIAL VIEWS 29 A Climate Scientist Reflects & Other Research Stories CLIMBERS FOR CLIMATE 32 Taking a Stand on Climate Change, Together 1CLIMB, INFINITE POTENTIAL 34 Kevin Jorgeson Breaks Down Walls by Building Them ON PUSHING 37 24 Hours Into the Black, the AAC Grief Fund AN ODE TO MOBILITY 40 The Range of Motion Project Tackles Cotopaxi YOSEMITE'S CAMP 4 43 The Center of the Climbing Universe REWIND THE CLIMB 47 The Tragedy of the 1932 American K2 Expedition BETA 48 Everything a Club Member Needs to Know PARTING SHOT 72 Jeremiah Watt on Travel & Life a Greg Kerzhner climbing Mr. -

Genre Bending Narrative, VALHALLA Tells the Tale of One Man’S Search for Satisfaction, Understanding, and Love in Some of the Deepest Snows on Earth

62 Years The last time Ken Brower traveled down the Yampa River in Northwest Colorado was with his father, David Brower, in 1952. This was the year his father became the first executive director of the Sierra Club and joined the fight against a pair of proposed dams on the Green River in Northwest Colorado. The dams would have flooded the canyons of the Green and its tributary, Yampa, inundating the heart of Dinosaur National Monument. With a conservation campaign that included a book, magazine articles, a film, a traveling slideshow, grassroots organizing, river trips and lobbying, David Brower and the Sierra Club ultimately won the fight ushering in a period many consider the dawn of modern environmentalism. 62 years later, Ken revisited the Yampa & Green Rivers to reflect on his father's work, their 1952 river trip, and how we will confront the looming water crisis in the American West. 9 Minutes. Filmmaker: Logan Bockrath 2010 Brower Youth Awards Six beautiful films highlight the activism of The Earth Island Institute’s 2011 Brower Youth Award winners, today’s most visionary and strategic young environmentalists. Meet Girl Scouts Rhiannon Tomtishen and Madison Vorva, 15 and 16, who are winning their fight to green Girl Scout cookies; Victor Davila, 17, who is teaching environmental education through skateboarding; Alex Epstein and Tania Pulido, 20 and 21, who bring urban communities together through gardening; Junior Walk, 21 who is challenging the coal industry in his own community, and Kyle Thiermann, 21, whose surf videos have created millions of dollars in environmentally responsible investments. -

Climbing.Com Helmets 317.Pdf

HEAD TRAUMA IS AMONG THE MOST FEARED AND CATASTROPHIC INJURIES IN CLIMBING. SO WHy aren’T MORE ROCK CLIMBERS WEARING HELMETS? By Dougald MacDonald Photography by Ben Fullerton ¬No-Brainer 40 | AUGUST 2013 CLIMBING.COM | 41 BetH RoddeN didN’t expect tRouBle oN tHe trad route, the long, easy east face of the is more dangerous: If you venture above mostly in the lower extremities. In 2009, Second Flatiron in Boulder, Colorado. base camp on Annapurna, you’ve got about the American Journal of Preventive Medi- ceNtRal pillaR of fReNzy Near the top, her partner asked if she’d a 1 in 25 chance of dying. By contrast, fa- cine published a study by Nicolas Nelson oN yosemite’s middle like to lead a short step. Barnes fell part- talities in rock climbing and bouldering are and Lara McKenzie of U.S. Consumer Prod- catHedRal Rock. afteR all, tHe 33-yeaR-old way up the pitch, popping out her naively very uncommon. Statistically, rock climbing uct Safety Commission data on climbers placed pro, and tumbled down the slab. is nowhere near as dangerous as the main- admitted to emergency rooms. Injuries to She sprained both ankles, strained a knee stream media (or your mom) would believe. the lower extremities accounted for nearly supeRstaR Had fRee climBed tHe and thumb, and chomped a big chunk out An average of about 30 climbers of all half of the climber ER visits between 1990 of her tongue. Before she came to a stop, disciplines die each year in the United and 2007, with ankles bearing the brunt of Nose of el cap she smacked the side of her head just States, from falling, rockfall, or any other the damage. -

Climbs and Expeditions 2004

156 CLIMBS AND EXPEDITIONS 2004 Accounts from the various climbs and expeditions of the world are listed geographically from north to south and from west to east within the noted countries. We begin our coverage with the Contiguous United States and move to Alaska in order for the climbs in Alaska’s Wrangell–St. Elias Mountains to segue into the St. Elias climbs in Canada. We encourage all climbers to submit accounts of notable activity, especially long new routes (generally defined as U.S. commitment Grade IV—full-day climbs—or longer). Please submit reports as early as possible (see Submissions Guidelines at www.AmericanAlpineClub.org). For conversions of meters to feet, multiply by 3.28; for feet to meters, multiply by 0.30. Unless otherwise noted, all reports are from the 2003 calendar year. NORTH AMERICA CONTIGUOUS UNITED STATES Washington Washington, trends and new routes. The summer of 2003 unfolded as the driest in a century, with rainfall 70-85% below normal. Seattle temperatures topped 70 degrees for a record 61 consecutive days. The unusual number of hot, dry days resulted in closed campgrounds, limited wilderness access, and fire bans. Pesky fires like the Farewell Creek in the Pasayten Wilderness, which was spotted June 29, obscured views throughout the Cascades, burned until autumn rains, and exhausted federal funds. Alpine glaciers and snow routes took on new character, as new climbing options appeared in the receding wake. A project by Lowell Skoog documented change by retracing, 50 years to the date, the photography of Tom Miller and the Mountaineers’ crossing of the Ptarmigan Traverse (www.alpenglow.org/climbing/ptarmigan-1953/index.html). -

5 Star Routes

1 | CALIFORNIA CLIMBER | | SPRING 2014 | 2 Climbingthat Solutions fit all your needs. ClimbTech’s Cable Draws ClimbTech’s permanent draws – Permadraws – are designed to be long-life rock climbing quickdraws that don’t wear or deteriorate like traditional nylon draws. Sustainable solutions and ClimbTech’s Legacy Bolt The new Legacy Bolt’s sleeve anchor now makes it possible to be installed and removed, allowing the same bolt hole to be used for rebolting. No need for a hammer, tighten down and you’re done! See new Legacy Bolt product videos at: Innovations climbtech.com/videos in climbing hardware. AWARD WINNER ClimbTech’s Wave Bolt The Wave Bolt is a glue-in rock climbing anchor, offering tremendous strength and increased resistance to corrosion. It combines the strength of glue-ins with the convenience of pitons. When installed in overhung terrain, the wavebolt will not slide out of the hole – like other glue-in bolts do – prior to the glue hardening. Power-Bolt™ Sleeve Anchor The Power-BoltTM is a heavy duty sleeve style anchor. Expansion is created by tightening a threaded bolt which draws a tapered cone expanding a sleve against the walls of the hole. These are the standard in new routing, available at climbtechgear.com ClimbTech’s Hangers A climbing hanger that combines the long life of stainless steel and strength in compliance with CE and UIAA standards. ClimbTech hangers are smooth to mitigate wear and tear on your carabiners. More at climbtechgear.com Follow us on Facebook Check us out on Vimeo /climbtech /climbtech 3 | CALIFORNIA CLIMBER | | SPRING 2014 | 4 photos: Merrick Ales & Felimon Hernandez California Climber CALIFORNIACLIMBERMAGAZINE.COM NO.