Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 9 Quiz

Name: ___________________________________ Date: ______________ 1. The diffusion of authority and power throughout several entities in the executive branch and the bureaucracy is called A) the split executive B) the bureaucratic institution C) the plural executive D) platform diffusion 2. A government organization that implements laws and provides services to individuals is the A) executive branch B) legislative branch C) judicial branch D) bureaucracy 3. What is the ratio of bureaucrats to Texans? A) 1 bureaucrat for every 1,500 Texas residents B) 1 bureaucrat for every 3,500 Texas residents C) 1 bureaucrat for every 4,000 Texas residents D) 1 bureaucrat for every 10,000 Texas residents 4. The execution by the bureaucracy of laws and decisions made by the legislative, executive, or judicial branch, is referred to as A) implementation B) diffusion C) execution of law D) rules 5. How does the size of the Texas bureaucracy compare to other states? A) smaller than most other states B) larger than most other states C) about the same D) Texas does not have a bureaucracy 6. Standards that are established for the function and management of industry, business, individuals, and other parts of government, are called A) regulations B) licensing C) business laws D) bureaucratic law 7. What is the authorization process that gives a company, an individual, or an organization permission to carry out a specific task? A) regulations B) licensing C) business laws D) bureaucratic law 8. The carrying out of rules by an agency or commission within the bureaucracy, is called A) implementation B) rule-making C) licensing D) enforcement 9. -

Texas Legislature, Austin, Texas, April 24, 1967

FOR RELEASE: MONDAY PM's APRIL 24, 1967 REMARKS OF VICE PRESIDENT HUBERT H. HUMPHREY TEXAS STATE LEGISLATURE AUSTIN, TEXAS APRIL 24, 1967 This is a very rare experience for me -- to be able to stand here and look out over all these fine Texas faces. Of course, I have had considerable practice looking into Texas faces -- sometimes I get the feeling that whoev·er wrote "The Eyes of Texas rr had me in mind. But what makes this experience so rare is that, this time, I am doing the talking. And I don't mind telling you: You may be in for it. But you don't need to worry. The point has already been made. One of your fellow Texans reminded me this morning that Austin was once the home of William Sidney Porter who wrote the 0. Henry stories -- and he .observed that 0. Henry and I had much in common: 0. Henry stories al'ltfays have surprise endings and in my speeches, the end is always a surprise, too. I am happy to be in Texas once again. As you realize, one of the duties of a Vice President is to visit the capitals of our friendly allies. Believe me; we are very grateful in Washington to have Texas on our side - that is, whenever you are. I am pleased today to bring to the members of the Legislature warm personal greetings from the President of the United States. He is on a sad mission today to pay the last respects of our nation to one of the great statesmen in the postwar world -- a man who visited Austin six years ago this month -- former Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of Germany. -

SCAS Chronology, 1969.Pdf

WEDNESDAY, January 1, 1969 .. j .""," \. I Tarrant County Junior College was ready to open tts Northeast campus, in the Hurst area, with 3,500 ex pected to enroll; and, the third campus (northwest) was in the early "thinking" stage. Also planned for 1969 opening was Texas Christian University's new science building, with hope that the added facilities and the early graduates of the TCJC system might help boost TCU's slightly-sagging enrollment. it: William Pearce had come from Texas ~' I/ Technological College to the presi dency of Texas Wesleyan NmIDmmnmmm~ " College; there was no plan to try for an enrollment increase (above 1,200), butAto attract better students seek ~r ing a good liberal education. In the "Fort Worth area," the only uncertainty was the legislative action and the recommendations of the < . ) Coordinating Board, Texas College and University System, on questions of UT-Arlington's future. REF: Fort Worth Press, Bronson Havard, "Colleges of FW Area Face Promising Year," 1-1-69. Media used Southwest Center for Ad vanced Studies President Gifford K. Johnson's annual review and report to faculty and staff in news copy and I! editorial statements. REF: Dallas Morning News, Douglas Domeier, "t-Irger of SCAS, UT • .. FRIDAY, January 3, 1969 ~Jd Boost to Area," undated. [email protected]!ffl¥lJlWf9.Imtlll~wm~W!D"9 • Texas should make full use of every available facility, public or private, that can contribute to educational needs, said the Dallas Morning News in an editorial. REF: Dallas Morning News, Editorial. "North Texas Gap," 1-3-6~.,: SUNDAY, January 5, 1969 Rep. -

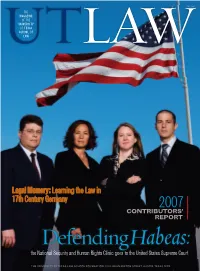

Fall 2007 Issue of UT Law Magazine

FALL 2007 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SCHOOL OF UTLAW LAW 2007 CONTRIBUTORS’ REPORT Defending Habeas: the Nationalational Security and Human Rights CCliniclinic ggoesoes ttoo tthehe United States SuSupremepreme CCourtourt THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS LAW SCHOOL FOUNDATION, 727 E. DEAN KEETON STREET, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 UTLawCover1_FIN.indd 2 11/14/07 8:07:37 PM 22 UTLAW Fall 2007 UTLaw01_FINAL.indd 22 11/14/07 7:46:29 PM InCamera Immigration Clinic works for families detained in Taylor, Texas The T. Don Hutto Family Residential Facility in Taylor, Texas currently detains more than one hundred immigrant families at the behest of the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. The facility, a former medium security prison, is the subject of considerable controversy regarding the way detainees are treated. For the past year, UT Law’s Immigration Clinic has worked to improve the conditions at Hutto. In this photograph, (left to right) Farheen Jan,’08, Elise Harriger,’08, Immigration Clinic Director and Clinical Professor Barbara Hines, Matt Pizzo,’08, Clinic Administrator Eduardo A Maraboto, and Kate Lincoln-Goldfi nch, ’08, stand outside the Hutto facility. Full story on page 16. Photo: Christina S. Murrey FallFall 2007 2007 UT UTLAWLAW 23 1 UTLaw01_FINAL.indd 23 11/14/07 7:46:50 PM 6 16 10 4 Home to Texas 10 Legal Memory: 16 Litigation, Activism, In the Class of 2010—students who Learning the Law in and Advocacy: entered the Law School in fall 2007— thirty-eight percent are Texas residents 17th-Century Germany Immigration Clinic works who left the state for their undergradu- ate educations and then returned for One of the remarkable books in the for detained families law school. -

Connelly's Return to Texas

4 ,(// Connelly's Return to Texas John 13:onnally is going back to the Lone Star 'State—and according to one of your reporters: "The decision was almost incomprehen- sible at a time when Connally seemed to be at the zenith of his power not only as the economic mastermind of the administra- tion, but also as a key foreign policy ad- viser." (Washington Post, Wednesday, May 17, 1972.) 1 hold that John B. Connally was waiting for the proper moment to leave the adminis- tration because he had already made all the hard-nosed, often unpopular, domestic and foreign economic policy decisions that Presi- dent Nixon wanted. As a student of Texas politics, let me pro- pose that his decision, to leaVe Washington crystallized when his political machine was sidetracked during the recent Texas Demo- cratic primary. Being the political operator that he is, how can Connally assure Presi- dent Nixon Texas support for his re-election with a hobbled political machine? Texas is a key state with 28 electoral votes. Nixon lost these to Humphrey in 1968. His beatable, Unbeatable protege Lt. Gov. Ben Barnes lost his bid for governor with a third place finish in a seven-man field. The incumbent Gov. Preston Smith did not carry a single one of the 254 counties in Texas, even with the shenanigans that took place in Duval County (shades of LW). Texas voters also ousted 18 or 17 other state legislators and the state's attorney general. That's not all: former Senator Ralph Yar- borough, a liberal by Texas standards, forced LBJ'a onetime aide "Barefoot" Sand- ers into a runoff. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

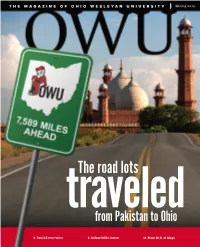

PDF Version of This Issue

THE MAGAZINE OF OHIO WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY Spring 2019 traveledThe road lots from Pakistan to Ohio 6 Touchdown twins 8 Indomitable intern 16 Mom M.D. at Mayo Students celebrate the Indian Holi festival March 22, organized by Horizons International Club, welcoming the coming beauty of spring. (Photo by Kit Weber ’20) 8 10 16 Features 8 Comfort Zones Anna L. Davies ’19 has made herself at home many places during her four years at OWU: in a Small Living Unit, as a Kappa Kappa Gamma, as a member of President’s Club, and as part of this magazine’s masthead. We crash her senior single in the Gillespie Honors House. 10 Bishops of Pakistan More than one-quarter of OWU’s current international student population comes from Pakistan, a tradition that goes back decades and has produced some truly remarkable alumni. 16 Solving maternal mortality at Mayo Katherine White Arendt ’98 has made it her life’s work to advocate for pregnant women through medicine, overseeing a team of more than 400 at the prestigious Mayo Clinic. Departments 02 LEADER’S LETTER 07 OWU TIMESCAPES 25 CALENDAR 04 FROM THE JAYWALK 22 FACULTY NOTES 26 CLASS NOTES 06 BISHOP BATTLES 24 ALUMNI HAPPENINGS 48 THE FINAL WORD ON THE COVER: Photo illustration by Jennifer Brinckerhoff Leader’s Letter International students and cultural events enrich campus s long ago as the 1890s, Ohio Wesleyan University attracted Astudents from South Asia. The flow of students from the subcontinent began as a result of OWU alumni who joined Methodists in establishing schools and other education centers all around the world. -

Annual Report

AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION 1-800-AHA-USA1 heart.org AMERICAN STROKE ASSOCIATION A division of the American Heart Association 1-888-4-STROKE (1-888-478-7653). For more information on life after stroke, ask for the stroke family “Warmline.” StrokeAssociation.org NATIONAL CENTER 7272 Greenville Avenue • Dallas, TX • 75231-4596 The American Heart Association is an Equal Opportunity Employer. ANNUAL REPORT ©2014, American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use prohibited. 11/14KB0747 “After a near-death experience and recovery from a debilitating illness, I have regained hope thanks to the support of the American Heart Association. Being able to share my story with others has been a major part of the healing process. I appreciate the AHA promoting survivors, their stories and their lives ongoing.” Cheryl Lawson of The Colony, Texas, who went into cardiac arrest triggered by a stress-induced condition known as “broken heart syndrome.” After receiving two stents to prop open arteries, her right main artery collapsed; her doctor said she was the first person he’d seen survive that. Lifestyle changes are a major part of her recovery, as is advocating for women to understand and improve their heart health. “Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women, yet too many of us ignore or downplay our symptoms, especially while pregnant. I’m living proof that the American Heart Association saves and improves lives. My husband, daughter and I are forever grateful.” Jill Russell of Woodridge, Ill., who went into heart failure while pregnant. Days after giving birth, her symptoms worsened. The problem finally was traced and treatment began. -

Hm Baggarly: One of the Last Of

H. M. BAGGARLY: ONE OF THE LAST OF THE PERSONAL JOURNALISTS by ILA MARGARET CRAWFORD, B.S., A.B., M.A. A THESIS IN MASS COMMUNICATIONS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Accepted Graduate School December, 1978 i\ryi'Oa^ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply indebted to Professor Ralph Sellmeyer for his direction of this thesis and to the other members of my committee. Professors Bill Dean and Philip Isett, for their helpful criticism. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE EARLY YEARS 9 III. POLITICAL ANALYST AND ADVOCATE 24 The Election of 1952 31 Dwight D. Eisenhower 32 The Election of 1960 35 John F. Kennedy 36 Lyndon B. Johnson 39 The Farm Problem 46 Richard M. Nixon 47 Gerald Ford 50 The Election of 1976 50 Jimmy Carter 52 IV. LOYAL TEXAS DEMOCRAT 57 Allan Shivers 63 Price Daniel 65 John Connally 67 Preston Smith 6 9 Dolph Briscoe 71 iii Ralph Yarborough 73 Lloyd Bentsen 77 Election of 1978 77 V. CITIZEN BAGGARLY, EDITOR AND MAN 79 VI. CONCLUSION 104 NOTES 106 SOURCES CONSULTED 122 IV CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Not many small-town editors are given the oppor tunity to work for a President of the United States. Yet, H. M. Baggarly, self-styled "country editor" and publisher of The Tulia Herald, once declined President Lyndon Johnson's offer to join his White House Staff as personal adviser and writer. Fervent in his loyalty to the Democratic Party and torn between his admiration for Johnson, his love for his community, and his concern for his newspaper, 'Baggarly described his decision as the most painful choice he ever had to make. -

Frances Farenthold: Texas’ Joan of Arc

FRANCES FARENTHOLD: TEXAS’ JOAN OF ARC Stephanie Fields-Hawkins Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2012 APPROVED: Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Major Professor Randolph B. Campbell, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Fields-Hawkins, Stephanie. Frances Farenthold: Texas’ Joan of Arc. Master of Arts (History), December 2012, 141 pp., bibliography, 179 titles. Born in 1926, Frances “Sissy” Tarlton Farenthold began her exploration of politics at a young age. In 1942, Farenthold graduated from Hockaday School for Girls. In 1945, she graduated from Vassar College, and in 1949, she graduated from the University of Texas School of Law. Farenthold was a practicing lawyer, participated in the Corpus Christi Human Relations Commission from 1964 to 1969, and directed Nueces County Legal Aid from 1965 to 1967. In 1969, she began her first term in the Texas House of Representatives. During her second term in the House (1971-1972), Farenthold became a leader in the fight against government corruption. In 1972, she ran in the Democratic primary for Texas governor, and forced a close run-off vote with Dolph Briscoe. Soon afterwards in 1972, she was nominated as a Democratic vice- presidential candidate at the Democratic convention, in addition to her nomination as the chairperson of the National Women’s Political Caucus. Farenthold ran in the Democratic primary for governor again in 1974, but lost decisively. From 1976 until 1980, she was the first woman president of Wells College, before coming back to Texas and opening a law practice. -

CITY of HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Ernest L. Shult-John B. Connally Jr. House AGENDA ITEM: III.b OWNERS: Stephen and Kaye Horn HPO FILE NO: 11L248 APPLICANTS: Same DATE ACCEPTED: Dec-22-2010 LOCATION: 2411 River Oak Boulevard - River Oaks HAHC HEARING: Jul-14-2011 SITE INFORMATION: Tract 32, Block 23, River Oaks Section Four, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a two-story, stucco clad single family residence. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The modern Ernest L. Shult-John B. Connally Jr. House was built in 1959 by Houston architect Ernest L. Shult as his own residence. Shult was born in Wharton County in 1901 and graduated from Rice University in 1923. By 1930, he was practicing as an architect in Houston, and during the 1940s and 50s, had his own architectural office on Fannin Street. Shult was also a longtime associate of Alfred C. Finn, a major Houston architect. Texas Governor John Connally Jr. and Nellie Connally moved into 2411 River Oaks Boulevard in January 1969 as their first private home after living in the Governor’s Mansion in Austin. Connally rose from humble farm boy roots to become a major figure in business, politics and government for half a century, during which time he served four U. S. Presidents. He was a lifelong friend and public servant with President Lyndon B. Johnson. He won the Bronze Star and the Legion of Merit after service in the U.S. Navy during WWII, where he rose in rank from ensign to lieutenant commander. -

The University of Texas at Austin GOV312L Professor Jim Enelow

The University of Texas at Austin GOV312L Professor Jim Enelow TEXAS POLITICAL HISTORY THIRD EXAM 1. Match the following names and identifications A William Hobby 1 elected Governor twice in the 1920s B Charles Culberson 2 U.S. Senator who retired after 1922 C Pat Neff 3 defeated in 1922 U.S. Senate run-off primary D Jim Ferguson 4 elected Governor in 1918 (a) A4, B3, C1, D2 (b) A4, B2, C1, D3 (c) A1, B2, C4, D3 (d) A4, B1, C2, D3 (e) A2, B4, C1, D3 2. Which of the following statements is correct? (a) During World War I, the Texas Legislature passed a law allowing women to serve on juries (b) In a special session in 1918, the Texas Legislature approved a 10-mile "dry zone" around Texas military bases (c) In 1919, Texas voters defeated a state constitutional amendment establishing the statewide prohibition of alcohol (d) During World War I, the Texas Legislature refused to pass a law making it a criminal offense to criticize the U.S. government (e) In 1919, the Texas Legislature refused to ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving women the vote 3. During the 1920s (a) Ma Ferguson was elected Governor twice on a platform of honesty in government (b) the Texas Legislature passed a law banning the teaching of evolution in the Texas public schools (c) the Ku Klux Klan became an important political force in Texas state politics, electing a U.S. Senator, members of the Texas Legislature, and taking control of several Texas cities (d) Pat Neff fought against the Ku Klux Klan, denouncing the Klan for a crime wave which had swept the state (e) Dan Moody used favoritism in awarding state contracts, leading to his defeat by Ma Ferguson in the 1928 governor's race 4.