THE LUNAR EXCURSION MODULE by ROBERT K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company/Ann Arbor, Michigan

1 72-4602^ FAPO, Haim Benzion, 1932- OPTIMAL SELENODETIC CONTROL. The Ohio State University, Ph.Dl, i'971‘ Geodesy University Microfilms, A X E R O X Company /Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED ! OPTIMAL SELENODETIC CONTROL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by • Halm Benzion Papo, B.Sc., M.Sc. The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by f U l t U , /■ llU 'gsileA ^ Advisor Department of Geodetic Science To Viola ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ' « ‘ It gives me a great pleasure to be able to extend my gratitude and appreciation to the many persons without whom this work would not have * been possible. From my parents I inherited a deep and sincere love for learning and an acute curiosity for the unknown and the unsurveyed. The Technion, Israels Institute of Technology and The Ohio State University provided me with the best education one could ask for in my field. Working in Room 231, Lord Hall on the OSU campus with other graduate students like myself has been a wonderful experience. There was an atmosphere of enthusiastic learning, of a fruitful exchange of ideas, of sharing ones excitement over finding an answer to a problem, of true friendship of people working together. The OSU Computer Center provided me generously with computer time needed for the study and through the invaluable assistance of Mr. John M. Snowden, I was able to make full use of its excellent facilities. Discussions on many conceptual and practical problems with Doctors Peter Meissl, Dean C. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

.72-4480 FAJEMIROKUN, Francis Afolabi, 1941- APPLICATION OF NEW OBSERVATIONAL SYSTEMS FOR SELENODETIC CONTROL. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Geodesy University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED APPLICATION OF NEW OBSERVATIONAL SYSTEMS FOR SELENODETIC CONTROL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Francis Afolabi Fajemirokun, B. Sc., M. Sc. The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by l/m /• A dviser Department of Geodetic Science PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have indistinct p rin t. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS To Ijigbola, Ibeolayemi and Oladunni ACKNOW LEDGEME NTS The author wishes to express his deep gratitude to the many persons, without whom this work would not have been possible. First and foremost, the author is grateful to the Department of Geodetic Science and themembers of its staff, for the financial support and academic guidance given to him during his studies here. In particular, the author wishes to thank his adviser Professor Ivan I. Mueller, for his encouragement, patience and guidance through the various stages of this work. Professors Urho A. Uotila, Richard H. Rapp and Gerald H. Newsom served on the author’s reading committee, and offered many valuable suggestions to help clarify many points. The author has also enjoyed working with other graduate students in the department, especially with the group at 231 Lord Hall, where there was always an atmosphere of enthusiastic learning and of true friendship. The author is grateful to the various scientists outside the department, with whom he had discussions on the subject of this work, especially to the VLBI group at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Ma s sachu s s etts . -

0 Lunar and Planetary Institute Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System THORIUM CONCENTRATIONS : IMBRIUM and ADJACENT REGIONS

THORIUM CONCENTRATIONS IN THE IMBRIUM AND ADJACENT REGIONS OF THE MOON. A1 bert E. Metzger, Eldon L. Haines*, Maria I. Etchegaray-Ramirez, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91103, and B. Ray Hawke, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822. The orbital gamma-ray spectrometer deconvolution technique restores some of the inherent spatial resolution and contrast lost because of the substan- tial field of view of the instrument. The technique has previously been applied to the observed Th distributions in the Aristarchus, Apennine, and Smythii regions of the Moon overflown by Apollo (1,2). Application has now been made to the Imbrium region using that portion of the data field extending from 10°W - 42OW, over which the data coverage lies between 18ON and 30°N. The area enclosed not only fills in the interval between the Aristarchus- and Apennine-centered regions previously reported but also provides overlap regions which serve as a test of consistency. It is characterized by basalt flows of various ages, depths, and spectral proper- ties, craters of Copernican and Eratosthenian age, and probable areas of pyroclastic mantling . The Aristarchus and Apennine regions contain two of the three areas of maximum radioactivity observed along the Apollo 15 and 16 data tracks. For both regions the undeconvolved values for the 2' x 2" pixels comprising the data base, range over a factor of 3-4 with maximum values in excess of 8.5 ppm. By comparison, the Imbrium field contains a contrast of only 1.5, the values being more uniformly high, but with an upper limit of about 6.5 ppm. -

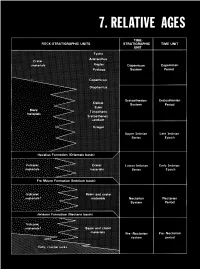

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

Testing Hypotheses for the Origin of Steep Slope of Lunar Size-Frequency Distribution for Small Craters

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Earth Planets Space, 55, 39–51, 2003 Testing hypotheses for the origin of steep slope of lunar size-frequency distribution for small craters Noriyuki Namiki1 and Chikatoshi Honda2 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kyushu University, Hakozaki 6-10-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan 2The Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Yoshinodai 3-1-1, Sagamihara 229-8510, Japan (Received June 13, 2001; Revised June 24, 2002; Accepted January 6, 2003) The crater size-frequency distribution of lunar maria is characterized by the change in slope of the population between 0.3 and 4 km in crater diameter. The origin of the steep segment in the distribution is not well understood. Nonetheless, craters smaller than a few km in diameter are widely used to estimate the crater retention age for areas so small that the number of larger craters is statistically insufficient. Future missions to the moon, which will obtain high resolution images, will provide a new, large data set of small craters. Thus it is important to review current hypotheses for their distributions before future missions are launched. We examine previous and new arguments and data bearing on the admixture of endogenic and secondary craters, horizontal heterogeneity of the substratum, and the size-frequency distribution of the primary production function. The endogenic crater and heterogeneous substratum hypotheses are seen to have little evidence in their favor, and can be eliminated. The primary production hypothesis fails to explain a wide variation of the size-frequency distribution of Apollo panoramic photographs. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Lunar Distances Final

A (NOT SO) BRIEF HISTORY OF LUNAR DISTANCES: LUNAR LONGITUDE DETERMINATION AT SEA BEFORE THE CHRONOMETER Richard de Grijs Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, Balaclava Road, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract: Longitude determination at sea gained increasing commercial importance in the late Middle Ages, spawned by a commensurate increase in long-distance merchant shipping activity. Prior to the successful development of an accurate marine timepiece in the late-eighteenth century, marine navigators relied predominantly on the Moon for their time and longitude determinations. Lunar eclipses had been used for relative position determinations since Antiquity, but their rare occurrences precludes their routine use as reliable way markers. Measuring lunar distances, using the projected positions on the sky of the Moon and bright reference objects—the Sun or one or more bright stars—became the method of choice. It gained in profile and importance through the British Board of Longitude’s endorsement in 1765 of the establishment of a Nautical Almanac. Numerous ‘projectors’ jumped onto the bandwagon, leading to a proliferation of lunar ephemeris tables. Chronometers became both more affordable and more commonplace by the mid-nineteenth century, signaling the beginning of the end for the lunar distance method as a means to determine one’s longitude at sea. Keywords: lunar eclipses, lunar distance method, longitude determination, almanacs, ephemeris tables 1 THE MOON AS A RELIABLE GUIDE FOR NAVIGATION As European nations increasingly ventured beyond their home waters from the late Middle Ages onwards, developing the means to determine one’s position at sea, out of view of familiar shorelines, became an increasingly pressing problem. -

Topographic Characterization of Lunar Complex Craters Jessica Kalynn,1 Catherine L

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 40, 38–42, doi:10.1029/2012GL053608, 2013 Topographic characterization of lunar complex craters Jessica Kalynn,1 Catherine L. Johnson,1,2 Gordon R. Osinski,3 and Olivier Barnouin4 Received 20 August 2012; revised 19 November 2012; accepted 26 November 2012; published 16 January 2013. [1] We use Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter topography data [Baldwin 1963, 1965; Pike, 1974, 1980, 1981]. These studies to revisit the depth (d)-diameter (D), and central peak height yielded three main results. First, depth increases with diam- B (hcp)-diameter relationships for fresh complex lunar craters. eter and is described by a power law relationship, d =AD , We assembled a data set of young craters with D ≥ 15 km where A and B are constants determined by a linear least and ensured the craters were unmodified and fresh using squares fit of log(d) versus log(D). Second, a change in the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Wide-Angle Camera images. d-D relationship is seen at diameters of ~15 km, roughly We used Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter gridded data to coincident with the morphological transition from simple to determine the rim-to-floor crater depths, as well as the height complex craters. Third, craters in the highlands are typically of the central peak above the crater floor. We established deeper than those formed in the mare at a given diameter. power-law d-D and hcp-D relationships for complex craters At larger spatial scales, Clementine [Williams and Zuber, on mare and highlands terrain. Our results indicate that 1998] and more recently, Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter craters on highland terrain are, on average, deeper and have (LOLA) [Baker et al., 2012] topography data indicate that higher central peaks than craters on mare terrain. -

Science Concept 3: Key Planetary

Science Concept 6: The Moon is an Accessible Laboratory for Studying the Impact Process on Planetary Scales Science Concept 6: The Moon is an accessible laboratory for studying the impact process on planetary scales Science Goals: a. Characterize the existence and extent of melt sheet differentiation. b. Determine the structure of multi-ring impact basins. c. Quantify the effects of planetary characteristics (composition, density, impact velocities) on crater formation and morphology. d. Measure the extent of lateral and vertical mixing of local and ejecta material. INTRODUCTION Impact cratering is a fundamental geological process which is ubiquitous throughout the Solar System. Impacts have been linked with the formation of bodies (e.g. the Moon; Hartmann and Davis, 1975), terrestrial mass extinctions (e.g. the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary extinction; Alvarez et al., 1980), and even proposed as a transfer mechanism for life between planetary bodies (Chyba et al., 1994). However, the importance of impacts and impact cratering has only been realized within the last 50 or so years. Here we briefly introduce the topic of impact cratering. The main crater types and their features are outlined as well as their formation mechanisms. Scaling laws, which attempt to link impacts at a variety of scales, are also introduced. Finally, we note the lack of extraterrestrial crater samples and how Science Concept 6 addresses this. Crater Types There are three distinct crater types: simple craters, complex craters, and multi-ring basins (Fig. 6.1). The type of crater produced in an impact is dependent upon the size, density, and speed of the impactor, as well as the strength and gravitational field of the target.