University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advances in the Interpretation and Analysis of Lunar Occultation Light Curves

A&A 538, A56 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118476 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Advances in the interpretation and analysis of lunar occultation light curves A. Richichi1,2 and A. Glindemann2 1 National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, 191 Siriphanich Bldg., Huay Kaew Rd., Suthep, Muang, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany Received 18 November 2011 / Accepted 23 December 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The introduction of fast 2D detectors and the use of very large telescopes have significantly advanced the sensitivity and accuracy of the lunar occultation technique. Recent routine observations at the ESO Very Large Telescope have yielded hundreds of events with results, especially in the area of binary stars, which are often beyond the capabilities of any other techniques. Aims. With the increase in the quality and in the number of the events, subtle features in the light curve patterns have occasionally been detected which challenge the standard analytical definition of the lunar occultation phenomenon as diffraction from an infinite straight edge. We investigate the possible causes for the observed peculiarities. Methods. We have evaluated the available statistics of distortions in occultation light curves observed at the ESO VLT, and compared it to data from other facilities. We have developed an alternative approach to model and interpret lunar occultation light curves, based on 2D diffraction integrals describing the light curves in the presence of an arbitrary lunar limb profile. We distinguish between large limb irregularities requiring the Fresnel diffraction formalism, and small irregularities described by Fraunhofer diffraction. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company/Ann Arbor, Michigan

1 72-4602^ FAPO, Haim Benzion, 1932- OPTIMAL SELENODETIC CONTROL. The Ohio State University, Ph.Dl, i'971‘ Geodesy University Microfilms, A X E R O X Company /Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED ! OPTIMAL SELENODETIC CONTROL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by • Halm Benzion Papo, B.Sc., M.Sc. The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by f U l t U , /■ llU 'gsileA ^ Advisor Department of Geodetic Science To Viola ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ' « ‘ It gives me a great pleasure to be able to extend my gratitude and appreciation to the many persons without whom this work would not have * been possible. From my parents I inherited a deep and sincere love for learning and an acute curiosity for the unknown and the unsurveyed. The Technion, Israels Institute of Technology and The Ohio State University provided me with the best education one could ask for in my field. Working in Room 231, Lord Hall on the OSU campus with other graduate students like myself has been a wonderful experience. There was an atmosphere of enthusiastic learning, of a fruitful exchange of ideas, of sharing ones excitement over finding an answer to a problem, of true friendship of people working together. The OSU Computer Center provided me generously with computer time needed for the study and through the invaluable assistance of Mr. John M. Snowden, I was able to make full use of its excellent facilities. Discussions on many conceptual and practical problems with Doctors Peter Meissl, Dean C. -

0 Lunar and Planetary Institute Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System THORIUM CONCENTRATIONS : IMBRIUM and ADJACENT REGIONS

THORIUM CONCENTRATIONS IN THE IMBRIUM AND ADJACENT REGIONS OF THE MOON. A1 bert E. Metzger, Eldon L. Haines*, Maria I. Etchegaray-Ramirez, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91103, and B. Ray Hawke, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822. The orbital gamma-ray spectrometer deconvolution technique restores some of the inherent spatial resolution and contrast lost because of the substan- tial field of view of the instrument. The technique has previously been applied to the observed Th distributions in the Aristarchus, Apennine, and Smythii regions of the Moon overflown by Apollo (1,2). Application has now been made to the Imbrium region using that portion of the data field extending from 10°W - 42OW, over which the data coverage lies between 18ON and 30°N. The area enclosed not only fills in the interval between the Aristarchus- and Apennine-centered regions previously reported but also provides overlap regions which serve as a test of consistency. It is characterized by basalt flows of various ages, depths, and spectral proper- ties, craters of Copernican and Eratosthenian age, and probable areas of pyroclastic mantling . The Aristarchus and Apennine regions contain two of the three areas of maximum radioactivity observed along the Apollo 15 and 16 data tracks. For both regions the undeconvolved values for the 2' x 2" pixels comprising the data base, range over a factor of 3-4 with maximum values in excess of 8.5 ppm. By comparison, the Imbrium field contains a contrast of only 1.5, the values being more uniformly high, but with an upper limit of about 6.5 ppm. -

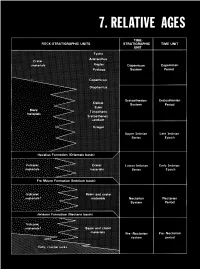

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

Testing Hypotheses for the Origin of Steep Slope of Lunar Size-Frequency Distribution for Small Craters

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Earth Planets Space, 55, 39–51, 2003 Testing hypotheses for the origin of steep slope of lunar size-frequency distribution for small craters Noriyuki Namiki1 and Chikatoshi Honda2 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kyushu University, Hakozaki 6-10-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan 2The Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Yoshinodai 3-1-1, Sagamihara 229-8510, Japan (Received June 13, 2001; Revised June 24, 2002; Accepted January 6, 2003) The crater size-frequency distribution of lunar maria is characterized by the change in slope of the population between 0.3 and 4 km in crater diameter. The origin of the steep segment in the distribution is not well understood. Nonetheless, craters smaller than a few km in diameter are widely used to estimate the crater retention age for areas so small that the number of larger craters is statistically insufficient. Future missions to the moon, which will obtain high resolution images, will provide a new, large data set of small craters. Thus it is important to review current hypotheses for their distributions before future missions are launched. We examine previous and new arguments and data bearing on the admixture of endogenic and secondary craters, horizontal heterogeneity of the substratum, and the size-frequency distribution of the primary production function. The endogenic crater and heterogeneous substratum hypotheses are seen to have little evidence in their favor, and can be eliminated. The primary production hypothesis fails to explain a wide variation of the size-frequency distribution of Apollo panoramic photographs. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

Water on the Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity

Water on The Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity Arlin Crotts (Columbia University) For centuries some scientists have argued that there is activity on the Moon (or water, as recounted in Parts I & II), while others have thought the Moon is simply a dead, inactive world. [1] The question comes in several forms: is there a detectable atmosphere? Does the surface of the Moon change? What causes interior seismic activity? From a more modern viewpoint, we now know that as much carbon monoxide as water was excavated during the LCROSS impact, as detailed in Part I, and a comparable amount of other volatiles were found. At one time the Moon outgassed prodigious amounts of water and hydrogen in volcanic fire fountains, but released similar amounts of volatile sulfur (or SO2), and presumably large amounts of carbon dioxide or monoxide, if theory is to be believed. So water on the Moon is associated with other gases. Astronomers have agreed for centuries that there is no firm evidence for “weather” on the Moon visible from Earth, and little evidence of thick atmosphere. [2] How would one detect the Moon’s atmosphere from Earth? An obvious means is atmospheric refraction. As you watch the Sun set, its image is displaced by Earth’s atmospheric refraction at the horizon from the position it would have if there were no atmosphere, by roughly 0.6 degree (a bit more than the Sun’s angular diameter). On the Moon, any atmosphere would cause an analogous effect for a star passing behind the Moon during an occultation (multiplied by two since the light travels both into and out of the lunar atmosphere). -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Arxiv:2107.09416V1

Draft version July 21, 2021 A Typeset using L TEX twocolumn style in AASTeX631 Estimation of the Eclipse Solar Radius by Flash Spectrum Video Analysis Luca Quaglia,1 John Irwin,2 Konstantinos Emmanouilidis,3 and Alessandro Pessi4 1Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 2Guildford, England, United Kingdom 3Thessaloniki, Greece 4Milan, Italy ABSTRACT The value of the eclipse solar radius during the 2017 August 21st total solar eclipse was estimated to be S⊙ = (959.95±0.05)”at 1 au with no significant dependence on wavelength. The measurement was obtained from the analysis of a video of the eclipse flash spectrum recorded at the southern limit of the umbral shadow path. Our analysis was conducted by extracting light curves from the flash spectrum and comparing them to simulated light curves. Simulations were performed by integrating the limb darkening function (LDF) over the exposed area of photosphere. These numerical integrations relied upon very precise computations of the relative movement of the lunar and solar limbs. Keywords: Solar radius (1488) — Solar eclipses (1489) — Flash spectrum (541) — Light curves (918) — Astronomical simulations (1857) 1. INTRODUCTION rameters is now below the milliarcsecond level while the accuracy of UT1 determination is well below the mil- The value of the solar radius at unit distance S⊙ is one of the fundamental quantities needed to perform very lisecond level. Satellite missions in the last decade have precise eclipse computations. Some of the other required vastly improved the knowledge of the topography of the inputs are: accurate ephemerides for the position of the Moon (Smith et al. 2017) to better than 10 m (corre- centres of mass of the Sun and Moon; accurate models sponding to about 5 mas at the mean geocentric dis- for the orientation of the Earth and Moon; and detailed tance of the Moon), allowing accurate computations of data on the topography of the Moon and Earth. -

INTERAGENCY REPORT: ASTROGEOLOGY 7 ADVANCED SYSTEMS TRAVERSE RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT by G

INTERAGENCY REPORT: ASTROGEOLOGY 7 ADVANCED SYSTEMS TRAVERSE RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT By G. E. Ulrich With a Section on Problems for Geologic Investigations of the Orientale Region of the Moon By R. S. Saunders July 1968 CONTENTS Page Abs tract . ............. 1 Introduct ion . •• # • ••• ••• .' • 2 Physiographic subdivision of the lunar surface 3 Site selection and preliminary traverse research. 8 Lunar topographic data •••••••.•.•••••• 17 Objectives and evaluation of traverse concepts • 20 Recommendations for continued traverse research .••• 26 Problems for geologic investigations of the Orientale region of the Moon, by R. S. Saunders 30 Introduct ion •.•• •••. 30 Physiography 30 Pre-Orbiter observations and i~terpretations 35 Geologic interpretations based on Orbiter photography ••••••••• 38 Conelusions •••• .•••. 54 References 56 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map and index to photographs of Orientale basin region ••••.•••••• 4 2. Crater-size frequency distributions of Orientale basin terrain units •••••• 11 3. Orientale basin region showing pre- liminary traverse evaluation areas ••••• 14 4. Effect of photographic exposure on shadow measurements 15 5. Alternate traverse areas for short and intermediate duration missions. North eastern sector of central Orientale basin ................... 24 6. Preliminary photogeologic map of the Orientale basin region. .•• .. .. 32 iii Page Figure 7. Sketch map of Mare Orientale region prepared from Earth-based telescopic photography • 36 8-21. Orbiter IV photographs of Orientale basin region showing-- . 8. Part of wr{nk1e ridge . 41 9. Slump scarps around steptoe and collapse depression . 44 10. Slump scarps along margin of central mare basin outlining collapse depression • • . • 44 11. Possible caldera 45 12. Northeast quadrant of inner ring showing central basin material and mare units 45 13.