Allsun O'malley Thesis Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

A Cognitive Approach to Gestural Life in Stephen Sondheim's Musical Genres

“MY ARM IS COMPLETE”: A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO GESTURAL LIFE IN STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S MUSICAL GENRES by Diana Louise Calderazzo AB, Smith College, 1999 MA, University of Central Florida, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE ARTS This dissertation was presented by Diana Louise Calderazzo It was defended on July 11, 2012 and approved by Marlene Behrmann, Professor, Department of Psychology, Carnegie Melon University Atillio Favorini, Professor, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Pittsburgh Kathleen George, Professor, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Director: Bruce McConachie, Professor, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright by Diana Louise Calderazzo 2012 iii “MY ARM IS COMPLETE”: A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO GESTURAL LIFE IN STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S MUSICAL GENRES Diana Louise Calderazzo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Traditionally, musical theatre has been accepted more as a practical field than an academic one, as demonstrated by the relative scarcity of lengthy theory‐based publications addressing musicals as study topics. However, with increasing scholarly application of cognitive theories to such fields as theatre and music theory, musical theatre now has the potential to become the topic of scholarly analysis based on empirical data and scientific discussion. This dissertation seeks to contribute such an analysis, focusing on the implied gestural lives of the characters in three musicals by Stephen Sondheim, as these lives exemplify the composer’s tendency to challenge traditional audience expectations in terms of genre through his music and lyrics. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

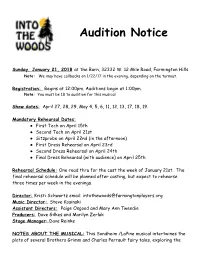

Audition Notice

Audition Notice Sunday, January 21, 2018 a t the Barn, 32332 W. 12 Mile Road, Farmington Hills Note: We may have callbacks on 1/22/17 in the evening, depending on the turnout. Registration: Begins at 12:00pm. Auditions begin at 1:00pm. Note: You must be 18 to audition for this musical. Show dates: April 27, 28, 29, May 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19. Mandatory Rehearsal Dates: ● First Tech on April 15th ● Second Tech on April 21st ● Sitzprobe on April 22nd (in the afternoon) ● First Dress Rehearsal on April 23rd ● Second Dress Rehearsal on April 24th ● Final Dress Rehearsal (with audience) on April 25th Rehearsal Schedule: One read thru for the cast the week of January 21st. The final rehearsal schedule will be planned after casting, but expect to rehearse three times per week in the evenings. Director: Kristi Schwartz email: [email protected] Music Director: Steve Kosinski Assistant Directors: Paige Osgood and Mary Ann Tweedie Producers: D ave Gilkes and Marilyn Zerlak Stage Manager: D ave Reinke NOTES ABOUT THE MUSICAL: This Sondheim /LaPine musical intertwines the plots of several Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault fairy tales, exploring the consequences of the characters‛ wishes and dreams. When a childless baker and his wife embark on a quest to begin a family, they interact with storybook characters from “Little Red Riding Hood”, “Jack and the Beanstalk”, “Rapunzel”, and “Cinderella”, during their journey. Will their wishes come true? And do they really want them to? Preparing for Auditions There will be two parts to the audition process for I nto the Woods . -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

Interview with Frank Oppenheimer

FRANK OPPENHEIMER (1912-1985) INTERVIEWED BY JUDITH R. GOODSTEIN November 16, 1984 Image courtesy of the San Francisco Exploratorium ARCHIVES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California Subject area Physics Abstract The younger brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Frank Friedman Oppenheimer was born in 1912 in New York City. After graduating as a bachelor of science in physics from Johns Hopkins in 1933, Oppenheimer traveled to Europe where he studied at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and Florence’s Istitudo di Arceti from 1933-35. He then entered the California Institute of Technology from where he received his doctoral degree in physics in 1939. Before joining his brother in Los Alamos in 1943, Oppenheimer held positions at Stanford, Berkeley’s Radiation Laboratory and the Y-12 Plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Following the http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechOH:OH_Oppenheimer_F War, Oppenheimer returned to Berkeley but then moved to the University of Minnesota where he embarked on studies of cosmic radiation. His research ended abruptly in 1949 after he was required to give testimony to the House Committee on Un-American Activities regarding his communist activities as a graduate student at Caltech. Not until 1961 did he return to university life at the University of Colorado. There he developed a variety of innovative teaching techniques, many of which were later incorporated in his design of the Exploratorium in San Francisco where Oppenheimer served as director. He died in Sausalito, California, in 1985. Conducted at the Exploratorium, this interview focuses on Oppenheimer’s years at the California Institute of Technology. Oppenheimer describes his work on beta- and gamma-ray spectroscopy and reminisces about C. -

Education Resource Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine

Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine INTO THE WOODS Education Resource Theatre Studies INTO THE WOODS RESOURCE – VCE THEATRE STUDIES UNIT 4 INTRODUCTION Figure 1: Victorian Opera - Into the Woods © Jeff Busby “A gem of a fairy tale with a soundscape of soaring melodies, shimmering colours and extraordinarily witty and moving lyrics.”– Richard Mills A darkly enchanting story about life after the ‘happily ever after’. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine reimagine the magical world of fairy tales as the classic stories of Jack and the Beanstalk, Cinderella, Little Red Ridinghood and Rapunzel collide with the lives of a childless baker and his wife. A brand new production of an unforgettable Tony award-winning musical. Into the Woods | Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine. 19 – 26 July 2014 | Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine By arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd Exclusive agent for Music Theatre International (NY) 2 hours and 50 minutes including one interval. Victorian Opera 2014 – Into the Woods Theatre Studies Resource 1 Figure 2: Victorian Opera - Into the Woods © Jeff Busby Into the woods and down the dell, The path is straight, I know it well. Into the woods, and who can tell What's waiting on the journey? In the Prologue to Into the Woods, the main characters sing these words and a magical quest begins. In many ways the experience you will have seeing Into the Woods will be similar. The audience must go ‘on the journey’ with the characters to truly experience the production; the audience’s presence ensures the characters’ reality. -

THE SINGER's MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Mezzo-Soprano/Belter Volumes

THE SINGER’S MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Series Guide and Indexes for Mezzo-Soprano/Belter Volumes • Alphabetical Song Index • Alphabetical Show Index Updated October 2019 KEY Accompaniment Book CDs Book/Online Audio S1 = Soprano, Volume 1 00361071 00740227 00000483 S2 = Soprano, Volume 2 00747066 00740228 00000488 S3 = Soprano, Volume 3 00740122 00740229 00000493 S4 = Soprano, Volume 4 00000393 00000397 00000497 S5 = Soprano, Volume 5 00001151 00001157 00001162 S6 = Soprano, Volume 6 00145258 00151246 00145264 S7 = Soprano, Volume 7 00287553 00293737 00293731 ST = Soprano, Teen's Edition 00230043 00230051 00230047 S16 = Soprano, 16-Bar Audition 00230039 - - Accompaniment Book CDs Book/Online Audio M1 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 1 00361072 00740230 00000484 M2 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 2 00740313 00740231 00000489 M3 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 3 00740123 00740232 00000494 M4 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 4 00000394 00000398 00000498 M5 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 5 00001152 00001158 00001163 M6 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 6 00145259 00151247 00145265 M7 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 7 00287554 00293738 00293734 MT = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Teen's Edition 00230044 00230052 00230048 M16 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, 16-Bar Audition 00230040 - - Accompaniment Book CDs Book/Online Audio T1 = Tenor, Volume 1 00361073 00740236 00000485 T2 = Tenor, Volume 2 00747032 00740237 00000490 T3 = Tenor, Volume 3 00740124 00074238 00000495 T4 = Tenor, Volume 4 00001153 00001160 00001164 T5 = Tenor, Volume 5 00001153 00001160 00001164 T6 = Tenor, -

SINGER's MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Master Index, All Volumes

THE SINGER’S MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY SERIES GUIDE AND INDEXES FOR ALL VOLUMES • Alphabetical Song Index • Alphabetical Show Index Updated September 2016 Key Accompaniment Book Only CDs Book/Audio S1 = Soprano, Volume 1 00361071 00740227 00000483 S2 = Soprano, Volume 2 00747066 00740228 00000488 S3 = Soprano, Volume 3 00740122 00740229 00000493 S4 = Soprano, Volume 4 00000393 00000397 00000497 S5 = Soprano, Volume 5 00001151 00001157 00001162 S6 = Soprano, Volume 6 00145258 00151246 00145264 ST = Soprano, Teen's Edition 00230043 00230051 00230047 S16 = Soprano, 16-Bar Audition 00230039 NA NA M1 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 1 00361072 00740230 00000484 M2 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 2 00747031 00740231 00000489 M3 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 3 00740123 00740232 00000494 M4 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 4 00000394 00000398 00000498 M5 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 5 00001152 00001158 00001163 M6 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 6 00145259 00151247 00145265 MT = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Teen's Edition 00230044 00230052 00230048 M16 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, 16-Bar Audition 00230040 NA NA T1 = Tenor, Volume 1 00361073 00740236 00000485 T2 = Tenor, Volume 2 00747032 00740237 00000490 T3 = Tenor, Volume 3 00740124 00740238 00000495 T4 = Tenor, Volume 4 00000395 00000401 00000499 T5 = Tenor, Volume 5 00001153 00001160 00001164 T6 = Tenor, Volume 6 00145260 00151248 00145266 TT = Tenor, Teen's Edition 00230045 00230053 00230049 T16 = Tenor, 16-Bar Audition 00230041 NA NA B1 = Baritone/Bass, Volume 1 00361074 00740236 00000486 B2 = Baritone/Bass, -

Disturbia 1 the House Down the Street: the Suburban Gothic In

Notes Introduction: Welcome to Disturbia 1. Siddons, p.212. 2. Clapson, p.2. 3. Beuka, p.23. 4. Clapson, p.14. 5. Chafe, p.111. 6. Ibid., p.120. 7. Patterson, p.331. 8. Rome, p.16. 9. Patterson, pp.336–8. 10. Keats cited in Donaldson, p.7. 11. Keats, p.7. 12. Donaldson, p.122. 13. Donaldson, The Suburban Myth (1969). 14. Cited in Garreau, p.268. 15. Kenneth Jackson, 1985, pp.244–5. 16. Fiedler, p.144. 17. Matheson, Stir of Echoes, p.106. 18. Clapson; Beuka, p.1. 1 The House Down the Street: The Suburban Gothic in Shirley Jackson and Richard Matheson 1. Joshi, p.63. Indeed, King’s 1979 novel Salem’s Lot – in which a European vampire invades small town Maine – vigorously and effectively dramatises this notion, as do many of his subsequent narratives. 2. Garreau, p.267. 3. Skal, p.201. 4. Dziemianowicz. 5. Cover notes, Richard Matheson, I Am Legend, (1954: 1999). 6. Jancovich, p.131. 7. Friedman, p.132. 8. Hereafter referred to as Road. 9. Friedman, p.132. 10. Hall, Joan Wylie, in Murphy, 2005, pp.23–34. 11. Ibid., p.236. 12. Oppenheimer, p.16. 13. Mumford, p.451. 14. Donaldson, p.24. 15. Clapson, p.1. 201 202 Notes 16. Ibid., p.22. 17. Shirley Jackson, The Road Through the Wall, p.5. 18. Friedman, p.79. 19. Shirley Jackson, Road, p.5. 20. Anti-Semitism in a suburban setting also plays a part in Anne Rivers Siddon’s The House Next Door and, possibly, in Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (in which the notably Aryan hero fends off his vampiric next-door neighbour with a copy of the Torah). -

INTO the WOODS Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine

INTO THE WOODS Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theaters Originally Produced by the Old Glober Theater, San Diego, CA Director Shawn K. Summerer Musical Director Choreographer Catherine Rahm Alison Mattiza Producers Lori A. Marple-Pereslete and Tony Pereslete Set Design Lighting Design Costume Design Tony Pereslete Robert Davis Kathy Dershimer Elizabeth Summerer and Jon Sparks Cast (in order of appearance) Narrator/Mysterious Man ................................................................................................. Ben Lupejkis Cinderella ..................................................................................................................... Heather Barnett Jack .............................................................................................................................. Brad Halvorsen Jack's Mother ................................................................................................................. Patricia Butler Milky White/Snow White ................................................................................................. Brandie June Baker ........................................................................................................................... Terry Delegeane Baker's Wife .......................................................................................................................