Background I. Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Localizing Into Chinese: the Two Most Common Questions White Paper Answered

Localizing into Chinese: the two most common questions White Paper answered Different writing systems, a variety of languages and dialects, political and cultural sensitivities and, of course, the ever-evolving nature of language itself. ALPHA CRC LTD It’s no wonder that localizing in Chinese can seem complicated to the uninitiated. St Andrew’s House For a start, there is no single “Chinese” language to localize into. St Andrew’s Road Cambridge CB4 1DL United Kingdom Most Westerners referring to the Chinese language probably mean Mandarin; but @alpha_crc you should definitely not assume this as the de facto language for all audiences both within and outside mainland China. alphacrc.com To clear up any confusion, we talked to our regional language experts to find out the most definitive and useful answers to two of the most commonly asked questions when localizing into Chinese. 1. What’s the difference between Simplified Chinese and Traditional Chinese? 2. Does localizing into “Chinese” mean localizing into Mandarin, Cantonese or both? Actually, these are really pertinent questions because they get to the heart of some of the linguistic, political and cultural complexities that need to be taken into account when localizing for this region. Because of the important nature of these issues, we’ve gone a little more in depth than some of the articles on related themes elsewhere on the internet. We think you’ll find the answers a useful starting point for any considerations about localizing for the Chinese-language market. And, taking in linguistic nuances and cultural history, we hope you’ll find them an interesting read too. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Sinitic Language and Script in East Asia: Past and Present

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 264 December, 2016 Sinitic Language and Script in East Asia: Past and Present edited by Victor H. Mair Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

History of China and Japan from 1900To 1976 Ad 18Bhi63c

HISTORY OF CHINA AND JAPAN FROM 1900TO 1976 A.D 18BHI63C (UNIT II) V.VIJAYAKUMAR 9025570709 III B A HISTORY - VI SEMESTER Yuan Shikai Yuan Shikai (Chinese: 袁世凱; pinyin: Yuán Shìkǎi; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty, becoming the Emperor of the Empire of China (1915–1916). He tried to save the dynasty with a number of modernization projects including bureaucratic, fiscal, judicial, educational, and other reforms, despite playing a key part in the failure of the Hundred Days' Reform. He established the first modern army and a more efficient provincial government in North China in the last years of the Qing dynasty before the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor, the last monarch of the Qing dynasty, in 1912. Through negotiation, he became the first President of the Republic of China in 1912.[1] This army and bureaucratic control were the foundation of his autocratic. He was frustrated in a short-lived attempt to restore hereditary monarchy in China, with himself as the Hongxian Emperor (Chinese: 洪憲皇帝). His death shortly after his abdication led to the fragmentation of the Chinese political system and the end of the Beiyang government as China's central authority. On 16 September 1859, Yuan was born as Yuan Shikai in the village of Zhangying (張營村), Xiangcheng County, Chenzhou Prefecture, Henan, China. The Yuan clan later moved 16 kilometers southeast of Xiangcheng to a hilly area that was easier to defend against bandits. There the Yuans had built a fortified village, Yuanzhaicun (Chinese: 袁寨村; lit. -

Basis Technology Unicode対応ライブラリ スペックシート 文字コード その他の名称 Adobe-Standard-Encoding A

Basis Technology Unicode対応ライブラリ スペックシート 文字コード その他の名称 Adobe-Standard-Encoding Adobe-Symbol-Encoding csHPPSMath Adobe-Zapf-Dingbats-Encoding csZapfDingbats Arabic ISO-8859-6, csISOLatinArabic, iso-ir-127, ECMA-114, ASMO-708 ASCII US-ASCII, ANSI_X3.4-1968, iso-ir-6, ANSI_X3.4-1986, ISO646-US, us, IBM367, csASCI big-endian ISO-10646-UCS-2, BigEndian, 68k, PowerPC, Mac, Macintosh Big5 csBig5, cn-big5, x-x-big5 Big5Plus Big5+, csBig5Plus BMP ISO-10646-UCS-2, BMPstring CCSID-1027 csCCSID1027, IBM1027 CCSID-1047 csCCSID1047, IBM1047 CCSID-290 csCCSID290, CCSID290, IBM290 CCSID-300 csCCSID300, CCSID300, IBM300 CCSID-930 csCCSID930, CCSID930, IBM930 CCSID-935 csCCSID935, CCSID935, IBM935 CCSID-937 csCCSID937, CCSID937, IBM937 CCSID-939 csCCSID939, CCSID939, IBM939 CCSID-942 csCCSID942, CCSID942, IBM942 ChineseAutoDetect csChineseAutoDetect: Candidate encodings: GB2312, Big5, GB18030, UTF32:UTF8, UCS2, UTF32 EUC-H, csCNS11643EUC, EUC-TW, TW-EUC, H-EUC, CNS-11643-1992, EUC-H-1992, csCNS11643-1992-EUC, EUC-TW-1992, CNS-11643 TW-EUC-1992, H-EUC-1992 CNS-11643-1986 EUC-H-1986, csCNS11643_1986_EUC, EUC-TW-1986, TW-EUC-1986, H-EUC-1986 CP10000 csCP10000, windows-10000 CP10001 csCP10001, windows-10001 CP10002 csCP10002, windows-10002 CP10003 csCP10003, windows-10003 CP10004 csCP10004, windows-10004 CP10005 csCP10005, windows-10005 CP10006 csCP10006, windows-10006 CP10007 csCP10007, windows-10007 CP10008 csCP10008, windows-10008 CP10010 csCP10010, windows-10010 CP10017 csCP10017, windows-10017 CP10029 csCP10029, windows-10029 CP10079 csCP10079, windows-10079 -

Implement Bopomofo by Opentype Font Feature.Key

Implement Bopomofo by OpenType font feature Bobby Tung 董福興 @W3C Digital Publishing Workshop KEIO Univ. Mita campus 2018/9/19 What is Bopomofo? • A phonetic system for Mandarin education in Taiwan. • Major input method for Han characters. → Layout Rules for Bopomofo • Bopomofo Ruby - implement and requirement W3C ebooks and i18n workshop 2013/6/4 https://bit.ly/2w3LEph • "The Manual of The Phonetic Symbols of Mandarin Chinese" Ministry of Education, Taiwan https://bit.ly/2htvssE HTML Markup Light tone <ruby>過<rt>˙ㄍㄨㄛ</rt></ruby> 2nd, 3rd, 4th tone marks <ruby>醒<rt>ㄒㄧㄥˇ</rt></ruby> Tabular ruby markup model(Only support by Firefox) <ruby><rb>你<rb>好<rb>嗎<rt>ㄋㄧˇ<rt>ㄏㄠˇ<rt>˙ㄇㄚ</ruby> → HTML Ruby Markup Extensions CSS Ruby Layout Module ruby-position: inter-character; is support by Webkit. Glyph issue Helvetica Source Han Sans ˙ U+02D9 DOT ABOVE ˊ U+02CA MODIFIER LETTER ACUTE ACCENT ˇ U+02C7 CARON ˋ U+02CB MODIFIER LETTER GRAVE ACCENT Source Han Sans traditional Chinese build fixed the glyphs of tone marks Last step: position of tone marks on browser spec on browser spec Tone marks' position when Bopomofo placed on the top It's ok but not readable for readers Last step: position of tone marks on browser spec on browser spec Tone marks' position when Bopomofo placed on the right side 2nd, 3rd, 4th tone marks should be placed to right side OpenType feature? • Which OpenType feature should we use? • Should we apply for new feature? • Do browsers support those features? Take a try! Hard to imply with Layout Ask expert for advice. -

Learning Chinese

Learning Chinese Chinese is the native language of over a billion speakers, more Language Family people than any other language. It is spoken in China, Singapore, Sino-Tibetan Malaysia, and in many overseas Chinese communities. Dialect 4UBOEBSE.BOEBSJOJTCBTFEPO/PSUIFSO Writing Systems: Chinese dialects. Standard Mandarin is Simplified, Traditional, and Pinyin the language of business, education, and the media in all regions of China, and is tSimplified Chinese (e.g. 汉语) characters are widely used in the People’s widely understood in almost every corner Republic of China. They are based on and share most of their characters of the Chinese-speaking world. with traditional Chinese characters. t Traditional Chinese (e.g. 漢語) characters are in widespread use in Your Learning Options Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and in many overseas Chinese communities. t3PTFUUB4UPOFPGGFSTZPVUIFDIPJDFPG Knowledge of traditional characters will also allow you to recognize many Simplified or Traditional characters characters in classical Chinese texts. for your course. Simplified Traditional tPinyin (e.g. hàn yǔ) is a method of writing Chinese using the Roman alphabet. Pinyin is a transliteration of characters into the Roman script and is used for teaching the language phonetically and for typing Chinese. t3PTFUUB4UPOFBMTPBMMPXTZPVUPMFBSOUP speak and understand spoken Chinese Language Tips without learning Chinese characters. t$IJOFTFJTXSJUUFOXJUIOPTQBDFTCFUXFFOXPSET If this is your objective, you can study your course in the pinyin script. t&BDIDIBSBDUFSJO$IJOFTFDPSSFTQPOETUPBTJOHMFTZMMBCMF tThe meaning of a Chinese syllable depends on the tone with which it is spoken. Chinese has four tones: t3PTFUUB4UPOFHJWFTZPVUIFBCJMJUZUP mā má mǎ mà view pinyin along with the characters. steady high 2 high rising 3 low falling-rising 4 falling You can use this feature as a t"UPOFNBZDIBOHFTMJHIUMZEFQFOEJOHPOUIFUPOFTPGJUTOFJHICPSJOH pronunciation guide for the characters you encounter in the course. -

Chinese Writing Written Mandarin As Noted Above, Mandarin Is Often Used to Refer to the Written Language of China As Well As to the Standard Spoken Language

Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin Julian K. Wheatley, MIT 3. Chinese writing Written Mandarin As noted above, Mandarin is often used to refer to the written language of China as well as to the standard spoken language. This is the language of composition learned in school and used by all educated Chinese regardless of the particular variety or regional languages that they speak. A Cantonese, for example, speaking Taishan Cantonese (Hoisan) at home and in the neighborhood, speaking something closer to standard Cantonese when s/he goes to Canton (city), and speaking Cantonese flavored Mandarin in certain formal or official situations, is taught to write a language that is different in terms of vocabulary, grammar and usage from both Hoisan and standard Cantonese. Even though s/he would read it aloud with Cantonese pronunciation, it would in fact be more easily relatable to spoken Mandarin in lexicon, grammar, and in all respects other than pronunciation. From Classical Chinese to modern written Chinese Written language always differs from spoken, for it serves quite different functions. But in the case of Chinese, the difference was, until the early part of the 20th century, extreme. For until then, most written communication, and almost all printed matter, was written in a language called Wényán in Chinese (‘literary language’), and generally known in English as Classical Chinese. As noted earlier, it was this language that served as a medium of written communication for the literate classes Classical Chinese was unlikely ever to have been a close representation of a spoken language. It is thought to have had its roots in the language spoken some 2500 years ago in northern China. -

International Language Environments Guide

International Language Environments Guide Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. Part No: 806–6642–10 May, 2002 Copyright 2002 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. All rights reserved. This product or document is protected by copyright and distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of this product or document may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Sun and its licensors, if any. Third-party software, including font technology, is copyrighted and licensed from Sun suppliers. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, docs.sun.com, AnswerBook, AnswerBook2, Java, XView, ToolTalk, Solstice AdminTools, SunVideo and Solaris are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon an architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. SunOS, Solaris, X11, SPARC, UNIX, PostScript, OpenWindows, AnswerBook, SunExpress, SPARCprinter, JumpStart, Xlib The OPEN LOOK and Sun™ Graphical User Interface was developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. for its users and licensees. Sun acknowledges the pioneering efforts of Xerox in researching and developing the concept of visual or graphical user interfaces for the computer industry. -

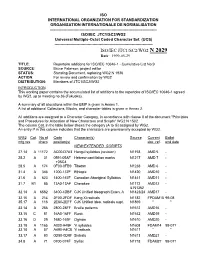

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

Generating Classical Chinese Poems from Vernacular Chinese

Generating Classical Chinese Poems from Vernacular Chinese Zhichao Yang1,∗ Pengshan Cai1∗, Yansong Feng2, Fei Li1, Weijiang Feng3, Elena Suet-Ying Chiu1, Hong Yu1 1 University of Massachusetts, MA, USA fzhichaoyang, [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] hong [email protected] 2 Institute of Computer Science and Technology, Peking University, China [email protected] 3 College of Computer, National University of Defense Technology, China [email protected] Abstract Since users could only interfere with the semantic of generated poems using a few input words, mod- Classical Chinese poetry is a jewel in the trea- els control the procedure of poem generation. In sure house of Chinese culture. Previous poem this paper, we proposed a novel model for classical generation models only allow users to employ Chinese poem generation. As illustrated in Figure keywords to interfere the meaning of gener- ated poems, leaving the dominion of gener- 1, our model generates a classical Chinese poem ation to the model. In this paper, we pro- based on a vernacular Chinese paragraph. Our ob- pose a novel task of generating classical Chi- jective is not only to make the model generate aes- nese poems from vernacular, which allows thetic and terse poems, but also keep rich semantic users to have more control over the semantic of the original vernacular paragraph. Therefore, of generated poems. We adapt the approach our model gives users more control power over the of unsupervised machine translation (UMT) to semantic of generated poems by carefully writing our task. We use segmentation-based padding and reinforcement learning to address under- the vernacular paragraph. -

Global Chinese 2018; 4(2): 217–246

Global Chinese 2018; 4(2): 217–246 Don Snow*, Shen Senyao and Zhou Xiayun A short history of written Wu, Part II: Written Shanghainese https://doi.org/10.1515/glochi-2018-0011 Abstract: The recent publication of the novel Magnificent Flowers (Fan Hua 繁花) has attracted attention not only because of critical acclaim and market success, but also because of its use of Shanghainese. While Magnificent Flowers is the most notable recent book to make substantial use of Shanghainese, it is not alone, and the recent increase in the number of books that are written partially or even entirely in Shanghainese raises the question of whether written Shanghainese may develop a role in Chinese print culture, especially that of Shanghai and the surrounding region, similar to that attained by written Cantonese in and around Hong Kong. This study examines the history of written Shanghainese in print culture. Growing out of the older written Suzhounese tradition, during the early decades of the twentieth century a distinctly Shanghainese form of written Wu emerged in the print culture of Shanghai, and Shanghainese continued to play a role in Shanghai’s print culture through the twentieth century, albeit quite a modest one. In the first decade of the twenty-first century Shanghainese began to receive increased public attention and to play a greater role in Shanghai media, and since 2009 there has been an increase in the number of books and other kinds of texts that use Shanghainese and also the degree to which they use it. This study argues that in important ways this phenomenon does parallel the growing role played by written Cantonese in Hong Kong, but that it also differs in several critical regards.