A Beast in the Pews: the Autopsy of Jane Doe - a Contextual Analysis Jeff Als Azar University of Washington-Tacoma, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

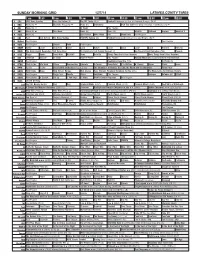

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Torts: Cases and Context Volume One

1 Torts: Cases and Context Volume One Eric E. Johnson Associate Professor of Law University of North Dakota School of Law eLangdell Press 2015 About the Author Eric E. Johnson is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of North Dakota. He has taught torts, intellectual property, sales, entertainment law, media law, sports law, employment law, and writing courses. He has twice been selected by students as the keynote speaker for UND Law’s graduation banquet. His writing on legal pedagogy has appeared in the Journal of Legal Education. With scholarly interests in science and risk, and in intellectual property, Eric’s publications include the Boston University Law Review, the University of Illinois Law Review, and New Scientist magazine. His work was selected for the Yale/Stanford/Harvard Junior Faculty Forum in 2013. Eric’s practice experience includes a wide array of business torts, intellectual property, and contract matters. As a litigation associate at Irell & Manella in Los Angeles, his clients included Paramount, MTV, CBS, Touchstone, and the bankruptcy estate of eToys.com. As in-house counsel at Fox Cable Networks, he drafted and negotiated deals for the Fox Sports cable networks. Eric received his J.D. cum laude from Harvard Law School in 2000, where he was an instructor of the first-year course in legal reasoning and argument. He received his B.A. with Highest and Special Honors from the Plan II program at the University of Texas at Austin. Outside of his legal career, Eric performed as a stand-up comic and was a top-40 radio disc jockey. -

Batman Arkham Asylum Free

FREE BATMAN ARKHAM ASYLUM PDF Dave McKean,Grant Morrison | 224 pages | 18 Nov 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401251246 | English | United States Arkham Asylum - Wikipedia Arkham Asylum first appeared in Batman Arkham Asylum Oct. Arkham Asylum serves as a psychiatric hospital for the Gotham City area, housing patients who are criminally Batman Arkham Asylum. Arkham's high-profile patients are often members of Batman's rogues gallery. Located in Gotham CityArkham Batman Arkham Asylum is where Batman's foes who are considered to be mentally ill are brought as patients other foes are incarcerated at Blackgate Penitentiary. Although it has had numerous administrators, some comic books have featured Jeremiah Arkham. Inspired by the works of H. Lovecraftand in particular his fictional city of Arkham, Massachusetts[2] [3] the asylum was introduced by Dennis O'Neil and Irv Novick and first appeared in Batman October ; much of its back-story was created by Len Wein during the s. Arkham Asylum has a poor security record and high recidivism rate, at least with regard to the high-profile cases—patients, such as Batman Arkham Asylum Joker, are frequently shown escaping at will—and those who are considered to no longer be mentally unwell and discharged tend to re-offend. Furthermore, several staff members, including its founder, Dr. Amadeus Arkhamand his nephew, director Dr. Jeremiah Arkhamas well as staff members Dr. Harleen QuinzelLyle Bolton and, in some incarnations, Dr. Jonathan Crane and Professor Hugo Strangehave become mentally unwell. In addition, prisoners with unusual medical conditions that prevent them from staying in a regular prison are housed in Arkham. -

Jane Doe and the Cradle of All Worlds Teachers Notes

JANE DOE AND THE CRADLE OF ALL WORLDS TEACHERS NOTES Written by Jeremy Lachlan Published by Hardie Grant Egmont in August 2018 SYNOPSIS With its towering columns and crummy stonework, the Manor looks more like an ancient ruin than anything. A gigantic gargoyle crowning the island, born of the cliffs themselves, as old as the sea and sky. Crumbling statues flank its windowless walls. Dying vines creep up its sides. For thousands of years, the people of Bluehaven worshipped it, praised it, journeyed through it to the Otherworlds, but it has stood like this – dormant, lifeless, closed to all – for well over a decade now. Fourteen years to be precise. Ever since me and Dad came to town. Jane Doe is all but alone in a world that hates her. Outcast from the day she and her father tumbled down the sacred steps of the Manor into Bluehaven, bringing earthquakes and destruction to the town, fourteen-year-old Jane is surrounded by people who hold her responsible for their misfortune. She and her father live in a basement owned by the Hollows, a local couple who take every opportunity to remind Jane that she is a curse upon the land. Jane’s only allies are Violet, the Hollows’ precocious and rebellious eight-year-old daughter; and her father, John Doe, who has been trapped, mute and unmoving, inside his own skin for as long as Jane can remember. She can feel an invisible thread connecting them, but her dad is unable to offer her any answers or comfort. The Hollows think she’s a freak, and resent her presence in their lives. -

Arkham Asylum: a Serious House on Serious Earth

ARKHAM ASYLUM: A SERIOUS HOUSE ON SERIOUS EARTH Adapted to script by Pedro F. Lopez Jr. Based on the graphic novel by Grant Morrison & Dave McKean [email protected] FADE IN: TEXT: ‘But I don’t want to go among mad people’, Alice remarked. ‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat, ‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” ‘How do you know I’m mad?’, Said Alice. ‘You must be’, said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’ Lewis Carroll “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” Like a ghostly apparition, the TEXT withers away. FADE IN: EXT. ARKHAM HOUSE - ROOFTOP - 1901 We open with a shot of the moon, caught in between two back lit statues of ANUBIS. It’s stormy. The sky’s stressed. The puddles on the roof reflect a semi-circular window. Mirroring the moon. EXT. ARKHAM HOUSE - ESTABLISHING The mansion broods in Gothic silence. It’s uninviting. ARKHAM (V.O.) From the journals of Amadeus Arkham. We experience a long CROSS-FADE: INT. ARKHAM HOUSE - CORRIDOR A young BOY, Amadeus ARKHAM, walks through a large corridor carrying a tray of tea and food. He’s dwarfed by his shadow. ARKHAM (V.O.) In the years following my Father’s death, I think it’s true to say that the house became my whole world. He walks up the stairs. 2. ARKHAM (V.O.) During the long period of mother’s illness, the house often seemed so vast, so confidently real, that by comparison, I felt little more than a ghost, haunting its corridors scarcely aware that anything could exist beyond those melancholy walls. -

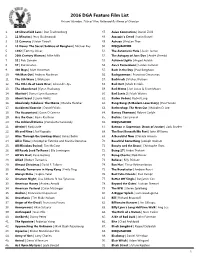

2016 DGA Feature Film List Entrant Number, Title of Film, Followed by Name of Director

2016 DGA Feature Film List Entrant Number, Title of Film, Followed By Name of Director 1.10 Cloverfield Lane | Dan Trachtenberg 47. Asian Connection | Daniel Zirilli 2.11 Minutes | Jerzy Skolimowski 48. Assassin's Creed | Justin Kurzel 3.13 Cameras | Victor Zarcoff 49. Astraea | Kristjan Thor 4.13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi | Michael Bay 50. DISQUALIFIED 5.1982 | Tommy Oliver 51. The Automatic Hate | Justin Lerner 6.20th Century Women | Mike Mills 52. The Autopsy of Jane Doe | André Øvredal 7.31 | Rob Zombie 53. Autumn Lights | Angad Aulakh 8.37 | Puk Grasten 54. Ava's Possessions | Jordan Galland 9.400 Days | Matt Osterman 55. Back in the Day | Paul Borghese 10.4th Man Out | Andrew Nackman 56. Backgammon | Francisco Orvananos 11.The 5th Wave | J Blakeson 57. Backtrack | Michael Petroni 12.The 9th Life of Louis Drax | Alexandre Aja 58. Bad Hurt | Mark Kemble 13.The Abandoned | Eytan Rockaway 59. Bad Moms | Jon Lucas & Scott Moore 14.Abattoir | Darren Lynn Bousman 60. Bad Santa 2 | Mark Waters 15.About Scout | Laurie Weltz 61. Baden Baden | Rachel Lang 16.Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie | Mandie Fletcher 62. Bang Gang (A Modern Love Story) | Eva Husson 17.Accidental Exorcist | Daniel Falicki 63. Barbershop: The Next Cut | Malcolm D. Lee 18.The Accountant | Gavin O'Connor 64. Barney Thomson | Robert Carlyle 19.Ace the Case | Kevin Kaufman 65. Baskin | Can Evrenol 20.The Adderall Diaries | Pamela Romanowsky 66. DISQUALIFIED 21.Aferim! | Radu Jude 67. Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice | Zack Snyder 22.Ali and Nino | Asif Kapadia 68. The Beat Beneath My Feet | John Williams 23.Alice Through the Looking Glass | James Bobin 69. -

CC Nov 05.Qxd

“where a good crime C r i m e can be had by all” c h r o n i c l e Issue #238 November 2005 P D JAMES Garry DISHER The Lighthouse 323pp Tp 29.95 Snapshot 337pp Tp 29.95 Combe Island, off the Cornish Coast, The neat suburban homes of the has a bloodstained history of piracy peninsula seem like an improbable and cruelty. Now privately owned, it setting for sex parties, blackmail and offers respite to over-stressed people in murder. Winter is closing in on the positions of high authority who coastal community of Waterloo. require privacy and guaranteed Behind closed doors, its residents security. But the peace of Combe is have some peculiar ways of keeping violated when a distinguished visitor warm. When Detective Inspector Hal is bizarrely murdered. Adam Dalgleish Challis is called to investigate the is called in to solve the mystery quickly brutal murder of Janine McQuarrie, and discreetly, but it is a difficult time shot in a deserted country lane as her for him and his depleted team. seven-year-old daughter looked on, Dalgleish is uncertain about his future with Emma Lavenham, his progress is hampered by lies and secrets. It doesn’t help that the woman he loves, while Detective Inspector Kate Miskin has Challis’s superior - bureaucrat, golfer and toady Superintendent her own emotional problems and the ambitious Anglo-Indian, McQuarrie - is Janine’s father-in-law. Or that Challis has his own Sergeant Francis Benton-Smith, is worried about working under personal demons to confront. -

Times Gone By

CAT-TALES TTIMES GGONE BBY CAT-TALES TTIMES GGONE BBY By Chris Dee Edited by David L. COPYRIGHT © 2002 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION TIMES GONE BY “But seas between us braid hae roar’d Sin auld lang syne.” --Robert Burns, Auld Lang Syne Tim and Stephanie were not prone to the angst-ridden tribulations of the older couples. It was New Year’s Eve and their conversation was devoted to the most famous song no one knows the words too: Auld Lang Syne. Robin had won the toss and he and Spoiler were stationed in a prime position overlooking Gotham Plaza, while the others patrolled less interesting parts of the city. At 12:01, Robin indulged in the common dating maneuver of quoting famous movies. In particular, Billy Crystal, When Harry Met Sally, 1989: “What does this song mean? My whole life, I don’t know what this song means…” It would have brought at least a chuckle from any girl in Gotham—except Stephanie Brown, whose father was the Cluemaster and whose mother was a teacher of English Literature and of Scottish descent. Her parents’ disparate interests in obscure trivia, Celtic pride, and a fierce admiration of the poet Burns meant that Steph was able to provide from memory the original 18th Century transcription and a modern translation of all four verses of the classic song. “It means Times Gone By.” “Isn’t that Casablanca?” Robin asked. “That’s AS Time GOES By.” “Oh. -

Results Sporting Spaniels (Cocker) Black 9 BB/G1 GCHG CH Conquest's Maze Runner

Warren County KC Sunday, April 4th, 2021 Group Results Sporting Spaniels (Cocker) Black 9 BB/G1 GCHG CH Conquest's Maze Runner. SR90376305 Spaniels (English Springer) 9 BB/G2 GCHB CH Crossroad Jockeyhill My Shot. SS01468001 Pointers (German Shorthaired) 28 BB/G3 GCHB CH Shadowland K Stardust On Fire JH. SS04214801 Vizslas 19 BB/G4 GCHS CH Hilldale Cmf Steichen's Studio Leitz JH BCAT. SR84099507 Hound Ibizan Hounds 7 BB/G1 CH Nahala's Winter Dragon TKN. HP55526405 Basenjis 11 BB/G2 GCHS CH Dark Moon's Project Mayhem. HP52043407 Beagles (15 Inch) 14 BB/G3 GCHS CH Glade Mill Goddess Of The Night. HP56901602 Dachshunds (Smooth) 15 BB/G4 CH Pipers Brisket Ms. HP57655601 Working Newfoundlands 9 BB/G1/RBIS GCHS CH Pouch Cove's Alright Alright Alright. WS59130701 Great Pyrenees 21 BB/G2 GCH CH Brynjulf Don't Cross The Streams CGC. WS60285104 Saint Bernards 7 BB/G3 GCHB CH Opdyke's Sesto Elemento. WS58133203 Cane Corso 9 BB/G4 GCHS CH Bravado's Mambo Italiano. WS61951701 Terrier Miniature Bull Terriers 5 BB/G1 GCH CH Aberdeen Spitfire Calling Norman Picklestripes @Bs. RN34080601 Border Terriers 17 BB/G2 GCH CH Sparravohn Cadence TKI. RN31830603 Kerry Blue Terriers 7 BB/G3 GCH CH Rocky Mountain Cross Into The Blue RN FDC CA BCAT RATN CGC Parson Russell Terriers 5 BB/G4 GCHB CH Highland Downs Perfectly Normal. RN32629402 Toy Havanese 5 BB/G1 GCHS CH That's Fire Power At Enginuity. TS29720001 Italian Greyhounds 26 BB/G2 CH Kashmir's Poppet. TS45104102 Pugs 7 BB/G3 CH Broughcastl's Bourne Id. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical REGISTRAR’S PERIODICAL, JULY 15, 2014 SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 0698009 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1817828 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2014 JUN 05 Registered Address: 133 Corporation Incorporated 2014 JUN 10 Registered COVEPARK CRESCENT NE, CALGARY ALBERTA, Address: 43 MCKINLEY WAY SE, CALGARY T3K5X7. No: 2118269402. ALBERTA, T2Z 1V6. No: 2018178281. 0815433 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1818877 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2014 JUN 02 Registered Address: 5233 - Corporation Incorporated 2014 JUN 02 Registered 49TH AVENUE, RED DEER ALBERTA, T4N6G5. Address: 1601, 333 - 11TH AVENUE S.W., CALGARY No: 2118252978. ALBERTA, T2R 1L9. No: 2018188777. 0846041 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1819160 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2014 JUN 02 Registered Address: 23007 Corporation Incorporated 2014 JUN 01 Registered TWP RD. 560, STURGEON COUNTY ALBERTA, Address: 1123 BELLEVUE AVE SE, CALGARY T0A1N1. No: 2118262712. ALBERTA, T2G 4L2. No: 2018191607. 0904442 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1819576 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2014 JUN 06 Registered Address: SUITE Corporation Incorporated 2014 JUN 03 Registered 2500, 10104 - 103 AVE, EDMONTON ALBERTA, Address: 1601, 333 - 11TH AVENUE S.W., CALGARY T5J1V3. No: 2118272505. ALBERTA, T2R 1L9. No: 2018195764. 0931503 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1819944 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2014 JUN 13 Registered Address: 542 Corporation Incorporated 2014 JUN 06 Registered SUNRISE WAY, TURNER VALLEY ALBERTA, Address: 1215 - 14 AVENUE SW, CALGARY T0L2A0. -

February 2008 .A SHOOTING in SIN CITY

MercantileEXCITINGSee section our NovemberNovemberNovember 2001 2001 2001 CowboyCowboyCowboy ChronicleChronicleChronicle(starting on PagepagePagePage 92) 111 The Cowboy Chronicle~ The Monthly Journal of the Single Action Shooting Society ® Vol. 21 No. 2 © Single Action Shooting Society, Inc. February 2008 .A SHOOTING IN SIN CITY . 6th Annual SASS Convention & Wild West Convention By Billy Dixon, SASS Life/Regulator #196 Photos by Black Jack McGinnis, SASS #2041 dress in funny old See HIGHLIGHTS on pages 74, 75 clothes, and some join to do some seri- and singles wearing their very best. ous costuming. Ladies adorned in close-fitting white From Wednes- or pearl satin and silk, or dazzling day evening when the eye in unexpected contrasts of Sugar Britches and I purple and green, or hand rolled yel- checked into the low roses on gun metal blue. Men as Riviera Hotel and strutted as peacocks in charcoal gray L Vegas, Casino we never set Prince Albert frocks over blood red Nevada – Well, the 6th Annual foot outside the vests. Long, trimmed moustaches SASS Convention & Wild West hotel until Sunday were shadowed by wide brimmed Christmas is added to the pages of morning when we Stetsons or tall silk stovepipe hats. history, and I for one am changed by checked out and The smell of exotic perfumes and its passing. Being wrong is a hateful departed for home. after-shaves wafted by with each experience for me, and I’ve been Between arrival and passing reveler. Layers of starched wrong. Having attended various departure, we had silk petticoats rustled with every Ends of Trail and other SASS func- one of the greatest step, while bustles added shape and tions for more than 20 years now, I SASS experiences texture to mystery. -

District Attorney Orange County, California Todd Spitzer

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA TODD SPITZER April 3, 2019 Sheriff Don Barnes Orange County Sheriff’s Department 550 N. Flower Street Santa Ana, CA 92703 Re: Deputy-Involved Shooting on January 19, 2018 Non-Fatal Incident involving Randall Wayne Allen District Attorney Investigations Case # S.A. 18-002 Orange County Sherriff’s Department Case # 18-002705 Orange County Crime Laboratory FR # 18-41247 Dear Sheriff Barnes, Please accept this letter detailing the Orange County District Attorney’s Office’s (OCDA) Investigation and legal conclusion in connection with the above listed incident involving on-duty Orange County Sheriff’s Department (OCSD) Deputies Robert Tomasko and Anthony Garza. Randall Wayne Allen, 23, survived his injuries. This incident occurred in the City of Lake Forest on January 19, 2018. OVERVIEW This letter contains a description of the scope and the legal conclusions resulting from the OCDA’s investigation of the January 19, 2018, non-fatal, officer-involved shooting of Randall Wayne Allen. The letter includes an overview of the OCDA’s investigative methodology and procedures employed, as well as a description of the relevant evidence examined, witnesses interviewed, factual findings, and legal principles applied in analyzing the incident and determining whether there was criminal culpability on the part of the OCSD deputies involved in the shooting. The format of this document was developed by the OCDA, at the request of many Orange County police agencies, to foster greater accountability and transparency in law enforcement. On January 19, 2018, Investigators from the OCDA Special Assignment Unit (OCDASAU) responded to this incident.