On Autistic Representation in Superhero Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man #16 Fantastic Four #7 Daredevil #2 Avengers No Road Home #3 (of 10) Superior Spider-Man #3 Age of X-Man X-Tremists #1 (of 5) Captain America #8 Captain Marvel Braver & Mightier #1 Savage Sword of Conan #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Betrayed #1 ($1) Invaders #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Avenger #1 ($1) Black Panther #9 X-Force #3 Marvel Comics Presents #2 True Believers Captain Marvel New Ms Marvel #1 ($1) West Coast Avengers #8 Spider-Man Miles Morales Ankle Socks 5-Pack Star Wars Doctor Aphra #29 Black Panther vs. Deadpool #5 (of 5) Marvel Previews Captain Marvel 2019 Sampler (FREE) Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #40 Mr. and Mrs. X Vol. 1 GN Spider-Geddon Covert Ops GN Iron Fist Deadly Hands of Kung Fu Complete Collection GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Peyer & Gutierrez GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Heroes in Crisis #6 (of 9) Flash #65 "The Price" part 4 (of 4) Detective Comics #999 Action Comics #1008 Batgirl #32 Shazam #3 Wonder Woman #65 Martian Manhunter #3 (of 12) Freedom Fighters #3 (of 12) Batman Beyond #29 Terrifics #13 Justice League Odyssey #6 Old Lady Harley #5 (of 5) Books of Magic #5 Hex Wives #5 Sideways #13 Silencer #14 Shazam Origins GN Green Lantern by Geoff Johns Book 1 GN Superman HC Vol. 1 "The Unity Saga" DC Essentials Nightwing Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Man-Eaters #6 Die Die Die #8 Outcast #39 Wicked & Divine #42 Oliver #2 Hardcore #3 Ice Cream Man #10 Spawn #294 Cold Spots GN Man-Eaters Vol. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

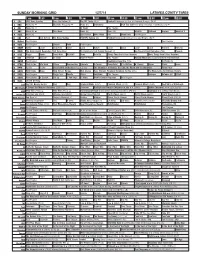

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Avengers Epic Collection: Once an Avenger Free

FREE AVENGERS EPIC COLLECTION: ONCE AN AVENGER PDF Stan Lee,Roy Thomas,Don Heck | 440 pages | 29 Nov 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785195825 | English | New York, United States Marvel Ultimate Collection, Complete Epic and Epic Collection lines - Wikipedia Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out Avengers Epic Collection: Once an Avenger date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Stan Lee was the former head writer, editorial and art director, publisher, and chairman of Marvel Comics, where he created or co-created enduring characters including Spider-Man, the X-Men, the Incredible Hulk, the Fantastic Four and many others. As the defining editorial voice for Marvel he introduced a generation to a new, more humanized approach to superheroes. Home 1 Kids' Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Avengers Epic Collection: Once an Avenger save with free shipping everyday! See details. Overview When Stan Lee turned the super-hero world on its head replacing Avengers founders Iron Man, Thor, Giant-Man and the Wasp with a trio of former super villains, readers thought he'd gone mad. As it turned out the only thing crazy was how insanely exciting the line-up of Captain America, Hawkeye, Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch would become! Despite the unbelievable heights the Avengers had reached under Lee, when he passed the title to Roy Thomas, the sky was the limit! Product Details About the Author. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Torts: Cases and Context Volume One

1 Torts: Cases and Context Volume One Eric E. Johnson Associate Professor of Law University of North Dakota School of Law eLangdell Press 2015 About the Author Eric E. Johnson is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of North Dakota. He has taught torts, intellectual property, sales, entertainment law, media law, sports law, employment law, and writing courses. He has twice been selected by students as the keynote speaker for UND Law’s graduation banquet. His writing on legal pedagogy has appeared in the Journal of Legal Education. With scholarly interests in science and risk, and in intellectual property, Eric’s publications include the Boston University Law Review, the University of Illinois Law Review, and New Scientist magazine. His work was selected for the Yale/Stanford/Harvard Junior Faculty Forum in 2013. Eric’s practice experience includes a wide array of business torts, intellectual property, and contract matters. As a litigation associate at Irell & Manella in Los Angeles, his clients included Paramount, MTV, CBS, Touchstone, and the bankruptcy estate of eToys.com. As in-house counsel at Fox Cable Networks, he drafted and negotiated deals for the Fox Sports cable networks. Eric received his J.D. cum laude from Harvard Law School in 2000, where he was an instructor of the first-year course in legal reasoning and argument. He received his B.A. with Highest and Special Honors from the Plan II program at the University of Texas at Austin. Outside of his legal career, Eric performed as a stand-up comic and was a top-40 radio disc jockey. -

Secret Wars II Free

FREE SECRET WARS II PDF Jim Shooter,Al Milgrom | 264 pages | 28 Dec 2011 | Marvel Comics | 9780785158301 | English | New York, United States Secret Wars II () Values & Price Guide Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Al Milgrom Illustrator. Last time Earth's heroes encountered the Beyonder, they fought for their lives. This time, they fight for all existence! A year after kidnapping the most powerful beings on Earth and pitting them against one another in a "Secret War" on a distant world, the omnipotent Beyonder comes to Earth Secret Wars II continue his study of humanity. As the Beyonder's understanding slowly grows, so too do his own desires - and even the lord of lies, Mephisto, fears what the Beyonder might finally decide he desires. Because if the Beyonder decides he wants to end all that is, even the combined might of Secret Wars II universe's Secret Wars II powers might not be enough to stop him! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published December 28th by Marvel first published March More Details Secret Wars 2Marvel Universe Events. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To Secret Wars II other readers questions about Secret Wars IIplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. -

Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee

NOTES CARDS WITH LINKS TO PICS (BLUE), FOLLOWED BY THOSE LISTED IN BOLD ARE HIGHEST PRIORITY I NEED MULTIPLES OF EVERY CARD LISTED, AS WELL AS PACKS, DECKS, UNCUT SHEETS, AND ENTIRE COLLECTIONS Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee - Character 5 Multipower Power Card Black Cat - Femme Fatale 8 Anypower Card Cyclops - Remove Visor 6 Anypower + 2 Basic Universe (Power Blast - Spawn) Ghost Rider - Hell on Wheels Any Character's - Flight, Massive Muscles, & Super Speed Human Torch - Character Artifacts (Linkstone, Myrlu Symbiote, The Witchblade) Iceman - Character Backlash - Mist Body Iron Man - Character Brass - Armored Powerhouse & Weapons Array Jubilee - Prismatic Flare Curse - Brutal Dissection Juggernaut - Battering Ram Darkness - Demigod of the Dark Rogue - Mutant Misslile Events - Witchblade on the Scene Scarlet Witch - Hex Power & Sorceress Slam (Non-Error) Grifter - Nerves of Steel Grunge - Danger Seeker IQ Killrazor - Outer Fury Any Hero - Power Leech Malebolgia - Character & Signed in Blood Apocalypse - Character Overtkill - One-Man Army Bishop - Character & Temporal Anomaly Ripclaw - Character & Native Magic Cable - Character & Askani' Son Shadowhawk - Backsnap & Brutal Revenge Carnage - Anarchy Spawn - Protector of the Innocent Deadpool - Don't Lose Your Head! Stryker - Armed and Dangerous Doctor Doom - Character & Diplomatic Immunity Tiffany - Character & Heavenly Agent Dr. Strange - Character Velocity - Internal Hardware, Quick Thinking, & Speedthrough Iron Man Character Violator - Darklands Army Ghost Rider - Character Voodoo -

The Muppets Take the Mcu

THE MUPPETS TAKE THE MCU by Nathan Alderman 100% unauthorized. Written for fun, not money. Please don't sue. 1. THE MUPPET STUDIOS LOGO A parody of Marvel Studios' intro. As the fanfare -- whistled, as if by Walter -- crescendos, we hear STATLER (V.O.) Well, we can go home now. WALDORF (V.O.) But the movie's just starting! STATLER (V.O.) Yeah, but we've already seen the best part! WALDORF (V.O.) I thought the best part was the end credits! They CHORTLE as the credits FADE TO BLACK A familiar voice -- one we've heard many times before, and will hear again later in the movie... MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) And lo, there came a day like no other, when the unlikeliest of heroes united to face a challenge greater than they could possibly imagine... STATLER (V.O.) Being entertaining? WALDORF (V.O.) Keeping us awake? MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) Look, do you guys mind? I'm foreshadowing here. Ahem. Greater than they could possibly imagine... CUT TO: 2. THE MUPPET SHOW COMIC BOOK By Roger Langridge. WALTER reads it, whistling the Marvel Studios theme to himself, until KERMIT All right, is everybody ready for the big pitch meeting? INT. MUPPET STUDIOS The shout startles Walter, who tips over backwards in his chair out of frame, revealing KERMIT THE FROG, emerging from his office into the central space of Muppet Studios. The offices are dated, a little shabby, but they've been thoroughly Muppetized into a wacky, cozy, creative space. SCOOTER appears at Kermit's side, and we follow them through the office.