Identifying with Superman: Addressing Superman's Career Through Burkean Identification Ryan Hoyle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the Represe

Research Space Journal article ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Goodrum, M. Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Goodrum, M. (2018) ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women. Gender & History, 30 (2). ISSN 1468-0424. Link to official URL (if available): https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12361 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Michael Goodrum Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane ran from 1958-1974 and stands as a microcosm of contemporary debates about women and their place in American society. The title itself suggests many of the topics about which women were concerned, or at least were supposed to concern them: the mediation of identity through heterosexual partnership, the pressure to marry and the simultaneous emphasis placed on individual achievement. Concerns about marriage and Lois’ ability to enter into it routinely provide the sole narrative dynamic for stories and Superman engages in different methods of avoiding the matrimonial schemes devised by Lois or her main romantic rival, Lana Lang. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

AKA Clark Kent) Middle Name Is Joseph

Superman’s (AKA Clark Kent) Middle Name Is Joseph. What’s that?! There in the sky? Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No! It’s the Man of Tomorrow! Superman has gone by many names over the years, but one thing has remained the same. He has always stood for what’s best about humanity, all of our potential for terrible destructive acts, but also our choice to not act on the level of destruction we could wreak. Superman was first created in 1933 by Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, the writer and artist respectively. His first appearance was in Action Comics #1, and that was the beginning of a long and illustrious career for the Man of Steel. In his unmistakable blue suit with red cape, and the stylized red S on his chest, the figure of Superman has become one of the most recognizable in the world. The original Superman character was a bald telepathic villain that was focused on world domination. It was like a mix of Lex Luthor and Professor X. Superman’s powers include incredible strength, the ability to fly. X-ray vision, super speed, invulnerability to most attacks, super hearing, and super breath. He is nearly unstoppable. However, Superman does have one weakness, Kryptonite. When exposed to this radioactive element from his home planet, he becomes weak and helpless. Superman’s alter ego is mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. He lives in the city of Metropolis and works for the newspaper the Daily Planet. Clark is in love with fellow reporter Lois Lane. -

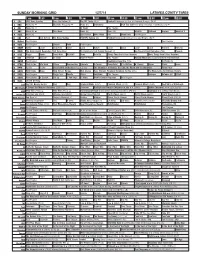

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Download Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3Rd Edition Pdf Ebook by Frank Miller

Download Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3rd Edition pdf ebook by Frank Miller You're readind a review Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3rd Edition ebook. To get able to download Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3rd Edition you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Sin City Volume 5: Family Values (3rd Edition) 128 pages Publisher: Dark Horse Books; 2nd Revised ed. edition (November 9, 2010) Language: English ISBN-10: 159307297X ISBN-13: 978-1593072971 Product Dimensions:6 x 0.4 x 9 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 3847 kB Description: Frank Millers first—ever original graphic novel is one of Sin Citys nastiest yarns to date! Starring fan—favorite characters Dwight and Miho, this newly redesigned edition sports a brand—new cover by Miller, some of his first comics art in years!Theres a kind of debt you cant ever pay off, not entirely. And thats the kind of debt Dwight owes Gail.... Review: Family Values is the 5th book in the fantastic Sin City series of graphic novels written and illustrated by mad comic book genius Frank Miller. Its a brief and uncharacteristically straightforward jaunt starring Basin Citys premiere anti-hero Dwight and the biggest/smallest bada$z ever to hit the pulp, deadly little Miho. Sin City began once Miller... Ebook File Tags: sin city pdf, yellow bastard pdf, frank miller pdf, -

Torts: Cases and Context Volume One

1 Torts: Cases and Context Volume One Eric E. Johnson Associate Professor of Law University of North Dakota School of Law eLangdell Press 2015 About the Author Eric E. Johnson is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of North Dakota. He has taught torts, intellectual property, sales, entertainment law, media law, sports law, employment law, and writing courses. He has twice been selected by students as the keynote speaker for UND Law’s graduation banquet. His writing on legal pedagogy has appeared in the Journal of Legal Education. With scholarly interests in science and risk, and in intellectual property, Eric’s publications include the Boston University Law Review, the University of Illinois Law Review, and New Scientist magazine. His work was selected for the Yale/Stanford/Harvard Junior Faculty Forum in 2013. Eric’s practice experience includes a wide array of business torts, intellectual property, and contract matters. As a litigation associate at Irell & Manella in Los Angeles, his clients included Paramount, MTV, CBS, Touchstone, and the bankruptcy estate of eToys.com. As in-house counsel at Fox Cable Networks, he drafted and negotiated deals for the Fox Sports cable networks. Eric received his J.D. cum laude from Harvard Law School in 2000, where he was an instructor of the first-year course in legal reasoning and argument. He received his B.A. with Highest and Special Honors from the Plan II program at the University of Texas at Austin. Outside of his legal career, Eric performed as a stand-up comic and was a top-40 radio disc jockey. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Master Comics #127 Pdf Free Download

MASTER COMICS #127 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Fawcett Publications | 38 pages | 28 Jul 2016 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781535560764 | English | none Master Comics #127 PDF Book Label Shipping and handling. Sort by A-Z Price. Label FC05E After managing to unmask Clark Kent in front of Lana Lang and others by machine-gunning him and revealing his costume beneath his clothes, the Toyman and the Prankster are captured by Superman. Other offers may also be available. Some scratches in the cardboard, but the piece was never taken out of the box for display and is in excellent condition. His power is incalculable. Distributed in the United Kingdom England. Earn up to 5x points when you use your eBay Mastercard. After a training session ends with the Torch complaining about Mr. Senor, the Senior Developer of the team. Toon meer Toon minder. He repeatedly asked Schott to "team up", but Schott refused. Items On Sale. Retrieved October 31, Contact the seller - opens in a new window or tab and request shipping to your location. We had a blast at C2E2!!! Orr to deploy his genetically engineered hero Hope, [9] but she almost kills the villain, until Superman saved him. Categories :. We know when you get your hands on this bad boy, you too will be saying "Man this thing is a Tank! If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. Universal Conquest Wiki. A female version of the Toyman named the Toywoman appears in Superman July Similar sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Similar sponsored items. -

Lois Lane Would Identify Clark Kent As Superman by His Body Language 1 November 2016

Lois Lane would identify Clark Kent as Superman by his body language 1 November 2016 understand that we're using information other than faces so we can get an insight into how we achieve this unique skill. "Our results show that we are able to use body motion when other cues are ambiguous or unavailable—so we basically assume that we can use body motion as a reliable cue to identity when other information is less available or reliable such as when a person is far away or when they're in bad lighting conditions. "I've always questioned why Lois Lane doesn't recognise Clark Kent or why Bruce Wayne has never been identified as Batman—now we know that they should be recognised based on their body motion!" Credit: University of Aberdeen More information: Karin S. Pilz et al. Idiosyncratic body motion influences person recognition, Visual Cognition (2016). DOI: Researchers from the University of Aberdeen have 10.1080/13506285.2016.1232327 found evidence that suggests that superheroes would be identifiable as their alter-ego personalities due to their unique body movements. Provided by University of Aberdeen The study published in the journal Visual Cognition, investigated how we are able to identify our peers, and found that when facial information is not available we can use body motion instead. The study was the first of its kind to use life-like avatars to get to the bottom of how we are so good at recognising each other. Dr Karin Pilz, from the School of Psychology at the University of Aberdeen said: "The current perception is that identity recognition is usually done on faces alone but obviously body motion is also important because we usually see people as whole bodies! "Even in difficult conditions, we are really good at person recognition and so, I think it's important to 1 / 2 APA citation: Lois Lane would identify Clark Kent as Superman by his body language (2016, November 1) retrieved 24 September 2021 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2016-11-lois-lane-clark-kent- superman.html This document is subject to copyright. -

A Celebration of Superheroes Virtual Conference 2021 May 01-May 08 #Depaulheroes

1 A Celebration of Superheroes Virtual Conference 2021 May 01-May 08 #DePaulHeroes Conference organizer: Paul Booth ([email protected]) with Elise Fong and Rebecca Woods 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This has been a strange year, to be sure. My appreciation to everyone who has stuck with us throughout the trials and tribulations of the pandemic. The 2020 Celebration of Superheroes was postponed until 2021, and then went virtual – but throughout it all, over 90% of our speakers, both our keynotes, our featured speakers, and most of our vendors stuck with us. Thank you all so much! This conference couldn’t have happened without help from: • The College of Communication at DePaul University (especially Gina Christodoulou, Michael DeAngelis, Aaron Krupp, Lexa Murphy, and Lea Palmeno) • The University Research Council at DePaul University • The School of Cinematic Arts, The Latin American/Latino Studies Program, and the Center for Latino Research at DePaul University • My research assistants, Elise Fong and Rebecca Woods • Our Keynotes, Dr. Frederick Aldama and Sarah Kuhn (thank you!) • All our speakers… • And all of you! Conference book and swag We are selling our conference book and conference swag again this year! It’s all virtual, so check out our website popcultureconference.com to see how you can order. All proceeds from book sales benefit Global Girl Media, and all proceeds from swag benefit this year’s charity, Vigilant Love. DISCORD and Popcultureconference.com As a virtual conference, A Celebration of Superheroes is using Discord as our conference ‘hub’ and our website PopCultureConference.com as our presentation space. While live keynotes, featured speakers, and special events will take place on Zoom on May 01, Discord is where you will be able to continue the conversation spurred by a given event and our website is where you can find the panels.