Darwin As 'Creative Tropical City'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

Melbourne - Geelong - Waurn Ponds: Regional Rail Link

VC12: MELBOURNE - GEELONG - WAURN PONDS: REGIONAL RAIL LINK BG. DMUs & locomotive-hauled trains. Ag18 Double track to Geelong. Single to Marshall. SG parallel West Werribee Jnc-North Geelong. For Warrnambool trains see VC13. Km. Ht. Open Samples Summary MELBOURNE SOUTHERN CROSS 9 910 930 West Tower Flyover Mon-Fri ex Melbourne Southern Cross: 500 to 015. Spion Kop Parallel to suburban & SG lines Peak: Frequent to Wyndham Vale (3), Geelong, South Geelong, Marshall Bridge over Maribyrnong River or Waurn Ponds. Footscray 16 917u 937u Off-peak: Every 20' alternately to South Geelong or Waurn Ponds. Parallel to suburban & SG lines. Sunshine 12.3 38 2014 922u 942u Mon-Fri ex Geelong: 446 to 2305. Ardeer 15.6 46 Peak: Frequent, most orginating at Waurns Ponds or Marshall, Deer Park 17.8 56 927 some ex South Geelong or Geelong, 4 ex Wyndham Vale. Deer Park Jnc 19.4 1884 Off-peak: Every 20' originating alternately at Waurn Ponds or South Geelong. Tarneit 29.3 935 955 WYNDHAM VALE 40.3 942 1002 Manor Jnc 47.4 2015 Sat ex Melbourne SX: 015, 115, 215 (bus) , 700 to 2325, 010, 110. Parallel to SG line. Every 40', stopping most stations to Waurn Ponds. Little River 55 33 949 Sat. ex Geelong: 531 to 2251. Lara 65 15 1857 955 1013 Every 40' ex Waurn Ponds usually stopping all stations. Corio 71.5 13 959 North Shore 75 15 1019 North Geelong 78 17 1004 1022 Sun ex Melbourne SX: 010, 110, 215 (bus) , 700 to 2110, 2240, 010. GEELONG arr 80.5 17 1866 1008 1027 Every 40' stopping most stations to Waurn Ponds. -

Victoria's Regional Centres – a Generation of Change Overview

Victoria’s regional centres – a generation of change Overview Published by the Department of Planning and Community Development, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne Vic 3002, November, 2010. ©Copyright State Government of Victoria 2010. This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by Justin Madden, Minister for Planning, Melbourne. Printed by Stream Solutions Pty Ltd. DISCLAIMER This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. ACCESSIBILITY If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, such as large print or audio, please telephone a Spatial Analysis and Research officer on 03 9208 3000 or email [email protected]. This publication is also published in PDF and Word formats on www.dpcd.vic.gov.au. Contents Executive summary i-ii 1 Introduction 1 2 The evidence base 2 2.1 Location and settlement pattern 2 2.2 Population change, 1981-2006 3 2.3 Peri-urban growth 4 2.4 Population change - projected 6 2.5 Age structure 7 2.6 Disability and ageing 8 2.7 Overseas born 9 2.8 Dwellings 10 2.9 Labour force 12 2.10 Manufacturing 14 2.11 The knowledge economy 16 2.12 Commuting 20 2.13 Educational attainment 22 2.14 Transport and communications 24 3 Prospects and challenges for the future 25 4 References 27 VICTORIA’S REGIONAL CENTRES – A GENERATION OF CHANGE – OVERVIEW Executive summary The population dynamics of regional centres and their suburbs remain largely under-researched in Australia. -

(LGANT) Annual General Meeting Has Elected a New Leadership Team for the Next Two Years That Includes

View this email in your browser The Local Government Association of the Northern Territory (LGANT) Annual General Meeting has elected a new leadership team for the next two years that includes: President Lord Mayor Kon Vatskalis City of Darwin Vice-President Municipal Vice-President Regional Councillor Kirsty Sayers-Hunt Councillor Peter Clee Litchfield Council Wagait Shire Council Executive Members Councillor Kris Civitarese Barkly Regional Council Deputy Mayor Peter Gazey Katherine Town Council Mayor Judy MacFarlane Roper Gulf Regional Council Councillor Georgina Macleod Victoria Daly Regional Council Deputy Mayor Peter Pangquee City of Darwin Councillor Bobby Wunungmurra East Arnhem Regional Council The LGANT Secretariat looks very much forward to working with the new President. He has a track record of getting things done, is an expert negotiator with an extensive network within the Territory and across Australia and will have a focus on equity, fairness, and good governance. There are six first-timers on the Executive drawn from all parts of the Territory, all bringing a unique set of skills and experience, with Mayor MacFarlane, Deputy Mayor Pangquee and Councillor Wunungmurra re- elected from the previous Board. The LGANT Executive will meet every month and has on its agenda advocacy on issues such as water security, housing, climate change adaptation, cyclone shelters, connectivity, infrastructure funding and working with the Territory and Commonwealth governments, councils, land councils and communities to assist in the progression of closing the gap targets. The election in Alice Springs marked the end of the tenure of Mayor Damien Ryan as President after ten years on the Executive and eight of those as President. -

Geelong Ballarat Bendigo Gippsland Western Victoria Northern Victoria

Project Title Council Area Grant Support GEELONG Growth Areas Transport Infrastructure Strategy Greater Geelong (C) $50,000 $50,000 Stormwater Service Strategy Greater Geelong (C) $100,000 Bannockburn South West Precinct Golden Plains (S) $60,000 $40,000 BALLARAT Ballarat Long Term Growth Options Ballarat (C) $25,000 $25,000 Bakery Hill Urban Renewal Project Ballarat (C) $150,000 Latrobe Street Saleyards Urban Renewal Ballarat (C) $60,000 BENDIGO Unlocking Greater Bendigo's potential Greater Bendigo (C) $130,000 $135,000 GIPPSLAND Wonthaggi North East PSP and DCP Bass Coast (S) $25,000 Developer Contributions Plan - 5 Year Review Baw Baw (S) $85,000 South East Traralgon Precinct Structure Plan Latrobe (C) $50,000 West Sale Industrial Area - Technical reports Wellington (S) $80,000 WESTERN VICTORIA Ararat in Transition - an action plan Ararat (S) $35,000 Portland Industrial Land Strategy Glenelg (S) $40,000 $15,000 Mortlake Industrial Land Supply Moyne (S) $75,000 $25,000 Southern Hamilton Central Activation Master Plan $90,000 Grampians (S) Allansford Strategic Framework Plan Warrnambool (C) $30,000 Parwan Employment Precinct Moorabool (S) $100,000 $133,263 NORTHERN VICTORIA Echuca West Precinct Structure Plan Campaspe (S) $50,000 Yarrawonga Framework Plan Moira (S) $50,000 $40,000 Shepparton Regional Health and Tertiary Grt. Shepparton (C) $30,000 $30,000 Education Hub Structure Plan (Shepparton) Broadford Structure Plan – Investigation Areas Mitchell (S) $50,000 Review Seymour Urban Renewal Precinct Mitchell (S) $50,000 Benalla Urban -

2021 Schedule P1

DATE HOME TEAM VISITOR WOMEN MEN VENUE DATE HOME TEAM VISITOR WOMEN MEN VENUE Sat 17 Apr Melbourne Tigers Sandringham Sabres 4:00pm 6:00pm MSAC Fri 14 May Hobart Chargers Diamond Valley Eagles 6:00pm 8:00pm KIN Sat 17 Apr Hobart Chargers Launceston / NW Tasmania 5:00pm 7:00pm KIN Sat 15 May Geelong Supercats Melbourne Tigers 5:00pm 7:00pm GEE Sat 17 Apr Frankston Blues Nunawading Spectres 5:30pm 7:30pm FRA Sat 15 May Albury Wodonga Bandits Waverley Falcons 6:00pm 8:00pm LJSC Sat 17 Apr Knox Raiders Geelong Supercats 5:30pm 7:30pm SBC Sat 15 May Bendigo Braves Eltham Wildcats 6:00pm 8:00pm BSL Sat 17 Apr Albury Wodonga Bandits Ballarat Miners/Rush 6:00pm 8:00pm LJSC Sat 15 May Dandenong Rangers Frankston Blues 6:00pm 8:00pm DAN ROUND 1 Sat 17 Apr Diamond Valley Eagles Dandenong Rangers 6:00pm 8:00pm CBS Sat 15 May Kilsyth Cobras Nunawading Spectres 6:00pm 8:00pm KIL Sat 17 Apr Eltham Wildcats Ringwood Hawks 6:00pm 8:00pm ELT Sat 15 May Ringwood Hawks Ballarat Miners/Rush 6:00pm 8:00pm RIN ROUND 5 Sat 17 Apr Kilsyth Cobras Waverley Falcons 6:00pm 8:00pm KIL Sat 15 May Mt Gambier Pioneers Knox Raiders 6:15pm 8:15pm MTG Sat 17 Apr Mt Gambier Pioneers Bendigo Braves 6:15pm 8:15pm MTG Sat 15 May Launceston / NW Tasmania Diamond Valley Eagles 7:00pm 7:30pm LAU/OBC Sun 16 May Eltham Wildcats Sandringham Sabres 12:00pm 2:00pm ELT Fri 23 Apr Bendigo Braves Frankston Blues 6:00pm 8:00pm BSL Sun 16 May Frankston Blues Bendigo Braves 12:30pm 2:30pm FRA Fri 23 Apr Hobart Chargers Ballarat Miners/Rush 6:00pm 8:00pm KIN Sun 16 May Melbourne Tigers Dandenong -

The Key to a Better City

THE KEY TO A BETTER CITY “It is time to ensure that Darwin has all the essential ingredients of a great city – and a plan to deliver for them” A MESSAGE FROM OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Darwin is currently facing significant economic challenges following the wind-down of the Ichthys Inpex construction phase and the decline of the mining sector. CBD office vacancies have risen once again and have been the highest in the nation with the lowest demand for three consecutive years. City retailers face stiff competition from expanding “This is a thought suburban centres, and the growth in the CBD residential population is slowing. piece presenting However, it is in such times where the opportunities and ideas rather than drive for change can be the greatest. fixed solutions. This thought piece sets out initiatives to help overcome economic challenges and trigger renewed focus on There is no silver Darwin CBD as the hub for economic growth in the NT. bullet.” The Property Council of Australia is committed to driving discussion on a range of matters to ensure the CBD is thriving for the benefit of its residents, visitors, traders and property owners. This thought piece presents ideas rather than fixed solutions. There is no silver bullet. What is clear is that a unified vision and approach is essential if we are to position the city for its future. Darwin is at a crossroads. After a historic residential, commercial, retail and industrial construction boom, our city is under pressure. Despite a rush of major projects and development, there is an overwhelming sense that there is something of a vacuum, with no clear vision or focus on how the city should move forward. -

2019/20 Darwin First

2019/20 ANNUAL REPORT DARWIN FIRST CITY OF DARWIN ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 INTRODUCTION ©2020 City of Darwin This work is copyright. Permission to reproduce information contained in this report must be obtained from: City of Darwin GPO Box 86, Darwin NT 0801 Phone: +61 8 8930 0300 Web: www.darwin.nt.gov.au Annual Report Legend This year, City of Darwin has utilised icons throughout the Annual Report to denote reference to other information or programs and projects impacted by Coronavirus as follows: CASE STUDY Indicates performance through a case study and may include references to other information or external websites. REFERENCE TO ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Indicates a reference or link to additional information which can be found on Council’s website www.darwin.nt.gov.au or other external website. COVID-19 Indicates where a program or project performance has been impacted by Coronavirus (COVID-19). The following icons are utilised throughout the report to demonstrate the level of performance that has been achieved in 2019/20. Definitions of performance are outlined below and commentary has been provided throughout the report to substantiate Council’s assessment of performance. This icon demonstrates Council’s programs or This icon demonstrates monitoring of Council’s deliverables are on track or projects have been performance for deliverables and projects is completed within budget and on schedule required. It may also indicate that a program or where Council has achieved its deliverables project did not achieve the desired result. or where a project has been completed. This icon demonstrates Council’s programs This icon demonstrates that a deliverable or or deliverables are in progress and project has not yet commenced, has been projects are almost complete. -

The HOT LIST

INSERT BACKGROUND IMAGE The HOT LIST March 2021 Melbourne, Victoria The Hot List Table of Contents Table of ● Key Pillar & Themes Indicator – 3 ● Upcoming Festival & Events – 4 contents ● New Tourism Products & Experiences – 6 ● Food & Drink Openings – 29 ● New Accommodation – 45 ● Future Accommodation Announcements – 63 The Hot List Key Pillars Tourism Products Food & Drink New Key & Experiences Openings Accommodation Pillars NATURE & WILDLIFE BAR & DINING HOTELS BOUTIQUE & LUXURY AQUATIC & COASTAL BARS HOTELS FOOD & DRINK RESTAURANTS HOSTELS MODERN & INDIGENOUS WINERIES, BREWERIES & GLAMPING & CAMPING CULTURE DISTILLERIES CAFÉS, BAKERIES & ECO-RESORTS & LODGES DESSERT SUSTAINABILITY Dark Mofo Festival, Tasmania INSERT BACKGROUND IMAGE FESTIVALS & EVENTS The Hot List Upcoming Festivals & Events UPCOMING April May June ● Brisbane Cycling Festival - Brisbane, ● Mountain Bike trails in Alice Springs - ● Sydney Solstice - Sydney Harbour, New Queensland (24 March - 12 April) Alice Springs, Northern Territory (1-4 South Wales (8 June - 20 June) FESTIVALS May) ● Field to Forest Festival - Oberon, New ● Noosa Eat & Drink Festival - Noosa, South Wales (1 - 30 April) ● Dark Skies Festival - Alice Springs, Queensland (10-13 June) Northern Territory (6 - 14 May) & EVENTS ● ● Sydney Royal Easter Show - Sydney, Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings - New South Wales (1 - 12 April) ● YIRRAMBOI Festival - Melbourne, Sydney, New South Wales (12 June - 19 Victoria (6 - 16 May) September) ● Thredbo Easter Adventure Carnival - Thredbo, New South Wales (2 - 18 April) ● Bendigo Writers Festival - Bendigo, ● Darwin Triple Crown Supercars - Please check event and Victoria (7 - 9 May) Darwin, Northern Territory (18 - 20 festival websites for further ● Four Winds Festival - Bermagui, New June) information around ticketing South Wales (2 - 4 April) ● Bass in the Grass - Darwin, Northern and bookings. -

Deakin University Geelong, Melbourne Or Warrnambool, Australia

[email protected] Deakin University Geelong, Melbourne or Warrnambool, A u s t r a l i a Comprehensive University, including courses on Australian culture Deakin's semester or academic year program study abroad program enriches the academic experience as it challenges a student to embrace a new culture and experience Australia while earning academic credit towards a Winthrop degree. Deakin has three principal campuses - from the busy multiculturalism of Melbourne, to the distinctive regional flavor of the bayside and coastal campuses of Geelong and Warrnambool. Website link: http://www.deakin.edu.au/future-students/international/study-abroad/sa-at- deakin/index.php Internships: As a Study Abroad student you are eligible to apply for internships provided you are in at least your third year of study, with a substantial portion of your major completed. The internship usually accounts for a quarter of a full-time semester study load. Currently internships are available in the areas of Social Work, Sociology, History, Journalism, Environmental Science, Public Relations, Media Arts, Policy, Graphic Design, Performing Arts (Dance/Drama) and Business. Website link: http://www.deakin.edu.au/future-students/international/study- abroad/internships.php Semester Dates (includes orientation) Application Deadline Fall: early July–early November Mar 1 for Fall study Spring: early February-late June Oct 1 for Spring study Location Facts Deakin University is located in Victoria, Australia's smallest mainland state. Victoria has Australia's second largest population with more than 4.5 million people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. It is a place of great contrasts - of ocean beaches and mountain ranges, deserts and forests, volcanic plains and vast sheep and wheat farms. -

2021 Afl Fixture

MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND 2021 AFL FIXTURE RD DATE MATCH TIME 1 THURSDAY, MAR 18 (THU N) RICHMOND VS. CARLTON 7:25PM 1 FRIDAY, MAR 19 (FRI N) COLLINGWOOD VS. WESTERN BULLDOGS 7:50PM 1 SATURDAY, MAR 20 (SAT EARLY) MELBOURNE VS. FREMANTLE 1:45PM 2 THURSDAY, MAR 25 (THU N) CARLTON VS. COLLINGWOOD 7:20PM 2 SUNDAY, MAR 28 (SUN AFT) HAWTHORN VS. RICHMOND 1:10PM 3 SATURDAY, APR 3 (SAT EARLY) RICHMOND VS. SYDNEY SWANS 1:45PM 3 MONDAY, APR 5 (MON D) GEELONG CATS VS. HAWTHORN 3:20PM 4 SATURDAY, APR 10 (SAT N) COLLINGWOOD VS. GWS GIANTS 7:25PM 4 SUNDAY, APR 11 (SUN AFT) MELBOURNE VS. GEELONG CATS 3:20PM 5 SATURDAY, APR 17 (SAT N) CARLTON VS. PORT ADELAIDE 7:25PM 5 SUNDAY, APR 18 (SUN AFT) HAWTHORN VS. MELBOURNE 3:20PM 6 SATURDAY, APR 24 (SAT N) MELBOURNE VS. RICHMOND 7:25PM 6 SUNDAY, APR 25 (SUN AFT) COLLINGWOOD VS. ESSENDON 3:20PM 7 FRIDAY, APR 30 TO SUNDAY, MAY 2 RICHMOND VS. WESTERN BULLDOGS 7 FRIDAY, APR 30 TO SUNDAY, MAY 2 ESSENDON VS. CARLTON 7 FRIDAY, APR 30 TO SUNDAY, MAY 2 COLLINGWOOD VS. GOLD COAST SUNS 8 FRIDAY, MAY 7 TO SUNDAY, MAY 9 RICHMOND VS. GEELONG CATS 8 FRIDAY, MAY 7 TO SUNDAY, MAY 9 MELBOURNE VS. SYDNEY SWANS 8 FRIDAY, MAY 7 TO SUNDAY, MAY 9 HAWTHORN VS. WEST COAST EAGLES 9 FRIDAY, MAY 14 TO SUNDAY, MAY 16 MELBOURNE VS. CARLTON 10 FRIDAY, MAY 21 TO SUNDAY, MAY 23 CARLTON VS. HAWTHORN 10 FRIDAY, MAY 21 TO SUNDAY, MAY 23 COLLINGWOOD VS. -

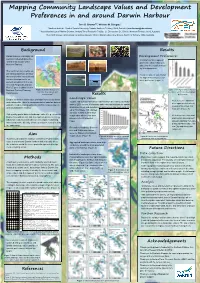

New PPGIS Research Identifies Landscape Values and Development

Mapping Community Landscape Values and Development Preferences in and around Darwin Harbour Tom D. Brewera,b, Michael M. Douglasc a Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0909, Australia ([email protected]). b Australian Institute of Marine Science, Arafura Timor Research Facility, 23 Ellengowan Dr., Brinkin, Northern Territory, 0810, Australia. a Research Institute of Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0909, Australia. Background Results Darwin Harbour is a highly val- Development Preferences ued and contested place; the A total of 647 development ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the preference sticker dots were Northern Territory. placed on the supplied maps by 80 respondents. The catchment is currently ex- periencing significant develop- ‘No development’ was, by far, ment and further industrial and the highest scoring develop- tourism development is ex- ment preference (Figure 7). pected, as outlined in the cur- rent draft Regional Land Use Plan1 (Figure 1) tabled by the Northern Territory Planning Figure 1. Darwin Harbour sec- Figure 7. Average scores (of a possi- tion of the development plan ble 100) for each of the development Commission. overview map1 Results preferences. Landscape Values Despite its obvious iconic value and significant use by locals Preference for industrial and visitors alike, there is no representative baseline data on To date 136 surveys have been returned from the mail-out question- development is clustered what the residents living within the catchment most value in naire to 2000 homes. Preliminary data entry and analysis for spatial around Palmerston and and around Darwin Harbour. landscape values and development preferences has been conduct- East Arm (Figure 8).