Stock Status of Atlantic Salmon in the Miramichi River 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Aucoin, F., D. Caissie, N. El-Jabi and N. Turkkan Department of Fisheries and Oceans Gulf Region Oceans and Science Branch Diadromous Fish Section P.O. Box 5030, Moncton, NB, E1C 9B6 2011 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Rapport technique canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropriés pour la publication dans un journal scientifique. -

Striped Bass Morone Saxatilis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence Population St. Lawrence Estuary Population Bay of Fundy Population SOUTHERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE POPULATION - THREATENED ST. LAWRENCE ESTUARY POPULATION - EXTIRPATED BAY OF FUNDY POPULATION - THREATENED 2004 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 43 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jean Robitaille for writing the status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Claude Renaud the COSEWIC Freshwater Fish Species Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation de bar rayé (Morone saxatilis) au Canada. Cover illustration: Striped Bass — Drawing from Scott and Crossman, 1973. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/421-2005E-PDF ISBN 0-662-39840-8 HTML: CW69-14/421-2005E-HTML 0-662-39841-6 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2004 Common name Striped Bass (Southern Gulf of St. -

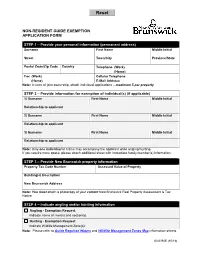

Non-Resident Guide Exemption Application Form

NON-RESIDENT GUIDE EXEMPTION APPLICATION FORM STEP 1 – Provide your personal information (permanent address) Surname First Name Middle Initial Street Town/City Province/State Postal Code/Zip Code Country Telephone (Work) (Home) Fax (Work) Cellular Telephone (Home) E-Mail Address Note: In case of joint ownership, attach individual applications – maximum 5 per property STEP 2 – Provide information for exemption of individual(s) (if applicable) 1) Surname First Name Middle Initial Relationship to applicant 2) Surname First Name Middle Initial Relationship to applicant 3) Surname First Name Middle Initial Relationship to applicant Note: Only one individual at a time may accompany the applicant while angling/hunting. If you require more space, please attach additional sheet with immediate family member(s) information. STEP 3 – Provide New Brunswick property information Property Tax Code Number Assessed Value of Property Building(s) Description New Brunswick Address Note: You must attach a photocopy of your current New Brunswick Real Property Assessment & Tax Notice STEP 4 – Indicate angling and/or hunting information Angling - Exemption Request Indicate name of river(s) and section(s). Hunting - Exemption Request Indicate Wildlife Management Zone(s). Note: Please refer to Guide Required Waters and Wildlife Management Zones Map information sheets 60-6392E (10/18) STEP 5 – Indicate your application method Option A Option B Option C Application by mail Application by fax Application in person at ERD, Fish & Wildlife Branch STEP 6 – Indicate your payment method Annual fee of $150 Canadian Funds (no tax) Check only one box. Cash Cheque Money Order Visa MasterCard Note: Do not send cash by mail. Please make cheque or money order payable in the amount of $150 Canadian Funds to the Minister of Finance, Province of New Brunswick. -

ATLANTIC SALMON INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN 2008-2012 GULF REGION Adult

ATLANTIC SALMON INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN 2008-2012 GULF REGION Adult Smolt Spawning Eggs Parr Eyed Eggs Fry Alevin Did you know that… • Salmon eggs are spawned in freshwater during the fall, incubate during the winter, and hatch in the spring. • Eggs hatch as fry and develop into parr over their first 2-4 years of life in freshwater. • Parr develop into smolts which leave their freshwater environment in the spring and migrate to the ocean. • Smolts that grow in the ocean for 1 year before they return to their native rivers to spawn are called grilse but smolts that grow in the ocean for 2 or more years before returning to spawn are called salmon. • After spawning in the fall, salmon and grilse are called kelts or black salmons and remain in rivers under the cover of ice until spring at which time they return to the ocean environment. • Salmon and grilse can spawn multiple times during their life. ATLANTIC SALMON INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN GULF REGION PLAN OVERVIEW The future well-being of the Atlantic salmon resource depends upon all parties working together through an integrated approach and in a harmonized manner. The Atlantic Salmon Integrated Management Plan for the Gulf Region is a five-year plan designed to engage the parties interested in the sustainable and orderly management of Atlantic salmon. It aim at strengthening their participation and to improve communications towards this endeavour. Engagement of the public and its community representatives should lead to better predictability and transparency in the decision making process. It is also meant to be an umbrella plan that allows for an adaptive and inclusive management approach based on the stakeholders' capacity. -

Active River Area

Active River Area (ARA) Framework Refinement: Developing Frameworks for Terrace and Meander Belt Delineation and Defining Optimal Digital Elevation Model for Future ARA Delineation by Shizhou Ma Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2020 © Copyright by Shizhou Ma, 2020 i Table of Contents List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... v List of Figures ................................................................................................................... vi Abstract ........................................................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations Used .............................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... x Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Motivation ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Problem to be Addressed........................................................................................ 3 1.3 Research Questions and Objectives ...................................................................... 6 1.4 Context -

Update of Indicators to 2017 of Adult Atlantic Salmon for the Miramichi River

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Gulf Region Science Response 2017/043 UPDATE OF INDICATORS TO 2017 OF ADULT ATLANTIC SALMON FOR THE MIRAMICHI RIVER (NB), SALMON FISHING AREA 16, DFO GULF REGION Context The last assessment of stock status of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) for Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Gulf Region was completed after the 2013 return year (DFO 2014) and updates on stock status for each of the four Salmon Fishing Areas (SFA 15-18) were prepared in 2014, 2015, and 2016 (DFO 2015a; DFO 2015b; DFO 2016; DFO 2017). DFO Fisheries and Aquaculture Management requested an update of the status of the Atlantic Salmon stock in the Miramichi River for 2017. Indicators for adult Atlantic Salmon for the Miramichi River are provided in this report. This Science Response Report results from the Science Response peer review meeting held in Moncton (N.B.) on December 19, 2017. No other publications will be produced from this science response process. Background All rivers flowing into the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence are included in DFO Gulf Region. Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) management areas in DFO Gulf Region are defined by four salmon fishing areas (SFA 15 to 18) encompassing portions of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and all of Prince Edward Island (Fig.1). The Miramichi River is the largest river in SFA 16 and DFO Gulf Region. Figure 1. Salmon Fishing Areas in the DFO Gulf Region. For management purposes, Atlantic Salmon are categorized as small salmon (grilse; fish with a fork length less than 63 cm) and large salmon (fish with a fork length equal to or greater than 63 cm). -

A Report on Recapture from a 1968 Native Salmon Smolt Tagging

RESTRICTED THE NORTHWEST ATLANTIC FISHERIES INTERNA nONAl COMMISSION FOR ICES/ICNAF Salmon Doc. 71/15 Serial No. 2541 (also ICNAF Res.Doc. 71/71) (B.g.14) ANNUAL MEETING - JUNE 1971 A Report on Recapture from a 1968 Native Salmon Smolt Tagging Project on the Miramichi River by G.E. Turner Resource Development Branch Department of Fisheries and Forestry of Canada Halifax, Nova Scotis l.t INTRODUCTION A program to evaluate the contribution of hatchery reared salmon smolts to sport and commercial fisheries in the Atlantic region was started in 196B. Part of this program included the tagging of wild native smolts in selected.rivers for comparison of returns with hatchery releases. This report presents results on 1969 and 1970 recaptures of wild native smolts tagged and released in the Miramichi River in 196B. The Miramichi River (Figure 1) is located in New Brunswick, has a drainage area of over 5,500 square miles and empties into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. 2.0 METHODS AND MATERIALS The native smolts used for the tagging project were captured in the estuary on their seaward migration and are representativ~ of the whole river and not one particular tributary. Fish were selected for tagging because of their vigor and good physical appearance (lack of scaled areas, abrasions, fun gal growth or'decayed fins). Although size was not a determining factor in selection of smolts for tagging, those under 12 cm. were culled as a precaution against damage from tagging needles. Tags used on all smolts were the modified Carlin type tied with black monofilament nylon twine and applied with a double needle tagging jig. -

In DFO Gulf Region (New Brunswick Salmon Fishing Areas 15 And

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Gulf Region Science Response 2015/008 UPDATE OF STOCK STATUS OF ATLANTIC SALMON (SALMO SALAR) IN DFO GULF REGION (NEW BRUNSWICK SALMON FISHING AREAS 15 AND 16) FOR 2014 Context The last assessment of stock status of Atlantic salmon for Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Gulf Region was completed after the 2013 return year (DFO 2014). DFO Fisheries and Aquaculture Management (FAM) requested an update of the status of the Atlantic Salmon stocks in DFO Gulf Region for 2014. Indicators for adult and juvenile Atlantic Salmon stocks of the Restigouche River (Salmon Fishing Area 15) and the Miramichi River (SFA 16) are provided in this report. Juvenile indices for the Buctouche River (SFA 16) are also provided. This Science Response Report results from the Science Response Process of December 11, 2014 on Indicators for Atlantic Salmon for Gulf New Brunswick rivers (SFA 15, 16). No additional publications from this process are anticipated. Background All rivers flowing into the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence are included in DFO Gulf Region. Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) management areas in DFO Gulf Region are defined by four salmon fishing areas (SFA 15 to 18) encompassing portions of the three Maritime provinces (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island). For management purposes, Atlantic Salmon are categorized as small salmon (grilse; fish with a fork length less than 63 cm) and large salmon (fish with a fork length equal to or greater than 63 cm). Analysis and Response Abundance indices of adult salmon Information on adult salmon abundance is provided for the Restigouche River of SFA 15 and the Miramichi River of SFA 16. -

Brief Presentation to the House of Common's Standing Committee On

Brief Presentation to the House of Common’s Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans on the Impact of the Rapid Increase of the Striped Bass in The Miramichi River and the Gulf of St. Lawrence BY: John Bagnall, Chair, Fisheries Committee, the New Brunswick Salmon Council DATE: March 4, 2019 The New Brunswick Salmon Council (the NBSC) is an Atlantic salmon conservation coalition comprised of 25 fish & game, environmental and First Nations organizations. A large majority of the members of our component organizations are primarily Atlantic salmon sport fishery participants and proponents, and they view wild salmon conservation as a means to achieve better recreational fishing results. Many also fish for other species, and support the establishment and maintenance of “good” fishing for species such as striped bass, brook trout, and smallmouth bass as well as salmon. As an introduction, the following is an explanation of the differences between recreationally fishing for Atlantic salmon and striped bass, and a discussion of what differentiates “good” from “bad” fishing for each. Fishing for “bright” Atlantic salmon (as opposed to post-spawned “black” salmon or kelts) is not for the impatient. Sea-run Atlantic salmon sport fishing in eastern Canada is conducted only by means of fly-fishing, a technique that takes patience for an angler to rise above even the level of ineptitude. “Bright” salmon are on their spawning run, and in fresh water do not feed. Therefore, even when employing proper fly-fishing techniques, it can be extremely difficult for anglers, to hook them. Salmon fishing occurs above the tidal limit in flowing water. -

A Literary and Historical Atlas of America

EVERYMAN .1 WILL? GO V-* ~~^--m^r >* IN THY MOST NEED THEE & BE THY GUIDE O GO BY THY SIDE ^OVyfcxvJL Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO by Sybille Pantazzi EVERYMAN'S LIBRARY EDITED BY ERNEST RHYS REFERENCE A L I TE R A R Y AND HISTORICAL ATLAS OF NORTH & SOUTH AMERICA THE PUBLISHERS OF LlBT^ATty WILL BE PLEASED TO SEND FREELY TO ALL APPLICANTS A LIST OF THE PUBLISHED AND PROJECTED VOLUMES TO BE COMPRISED UNDER THE FOLLOWING THIRTEEN HEADINGS: TRAVEL ^ SCIENCE ^ FICTION THEOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY HISTORY ^ CLASSICAL FOR YOUNG PEOPLE ESSAYS $ ORATORY POETRY & DRAMA BIOGRAPHY REFERENCE ROMANCE IN FOUR STYLES OF BINDING; CLOTH, FLAT BACK, COLOURED TOP; LEATHER, ROUND CORNERS, GILT TOP; LIBRARY BINDING IN CLOTH, & QUARTER PIGSKIN LONDON: J. M. DENT & SONS, LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO. I ALITERARYS HISTORICAL ATLAS OF AMERICA? J G.BARTHOLOMEW LL.D LONLON:PUBL4SHED hyJMDENTS-SONS^ ANP IN NEW YORK BYE-P DUTTONSCO / INTRODUCTION WHEN General Hamilton spoke in the Federalist over a " century ago of an empire, in many respects the most inter- esting in the world," meaning the United States of America, he did not, he could not, foresee the vast growth of his country and its northern and southern neighbours which this book portrays. The volume is the third in a series of small atlases, meant to cover in turn the whole globe, and to do it in a way to knit up geographical and historical knowledge with the facts of commerce and the literary record of each land or region. One chief purpose of these maps is to trace clearly " the development of the United States, beginning with the " most remarquable parts of the New England of the Pilgrim Fathers, described by Captain John Smith in 1614, and not forgetting the territories of the old American-Indian nations. -

Stock Status of Atlantic Salmon in the Miramishi River, 1995

Not to be cited without Ne pas citer sans permission of the authors' autori sation des auteurs ' DFO Atlantic Fisheries MPO Pêches de l'Atlantique Research Document 96/124 Document de recherche 96/124 Stock status of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in the Miramichi River, 1995 by G. Chaput, M. Biron, D. Moore, B. Dube2, C. Ginnish', M. Hambrook, T. Paul`, and B . Scott Dept. of Fisheries and Oceans Science Branch P.O. Box 5030 Moncton, NB E 1 C 9B6 'New Brunswick Dept . of Natural Resources and Energy Miramichi, NB 'Eel Ground First Nations Eel Ground, N B 4 Red Bank First Nations Red Bank, NB 'This series documents the scientific basis 'La présente série documente les bases for the evaluation of fisheries resources in scientifiques des évaluations des ressources Atlantic Canada . As such, it addresses the halieutiques sur la côte atlantique du issues of the day in the time frames required Canada. Elle traite des problèmes courants and the documents it contains are not selon les échéanciers dictés . Les documents intended as definitive statements on the qu'elle contient ne doivent pas être subjects addressed but rather as progress considérés comme des énoncés définitifs sur reports on ongoing investigations. les sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports d'étape sur les études en cours . Research documents are produced in the Les Documents de recherche sont publiés official language in which they are provided dans la langue officielle utilisée dans le to the secretariat . manuscrit envoyé au secrétariat . 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT . .. .. .... .... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. ... ... .... .. ... .... .. 3 SUMMARY SHEETS . .... ... .. ...... .... .. .... .... ... .... ... ... .... ..4 INTRODUCTION . ... .... .... ... .... .. ... .... .... ... .... .. ... 7 DESCRIPTION OF FISHERIES . -

Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations Règlement De Pêche Des Provinces Maritimes TABLE of PROVISIONS TABLE ANALYTIQUE

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Maritime Provinces Fishery Règlement de pêche des Regulations provinces maritimes SOR/93-55 DORS/93-55 Current to September 11, 2021 À jour au 11 septembre 2021 Last amended on May 14, 2021 Dernière modification le 14 mai 2021 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. ... [...] Inconsistencies in