Understanding the “Galakei” Appeal; a Study of Language and Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

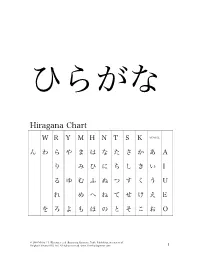

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text. -

Implementing Cross-Locale CJKV Code Conversion

Implementing Cross-Locale CJKV Code Conversion Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/ujip/unicode/iuc13-c2-paper.pdf ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/ujip/unicode/iuc13-c2-slides.pdf Code Conversion Basics dc • Algorithmic code conversion — Within a single locale: Shift-JIS, EUC-JP, and ISO-2022-JP — A purely mathematical process • Table-driven code conversion — Required across locales: Chinese ↔ Japanese — Required when dealing with Unicode — Mapping tables are required — Can sometimes be faster than algorithmic code conversion— depends on the implementation September 10, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Adobe Systems Incorporated Code Conversion Basics (Cont’d) dc • CJKV character set differences — Different number of characters — Different ordering of characters — Different characters September 10, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Adobe Systems Incorporated Character Sets Versus Encodings dc • Common CJKV character set standards — China: GB 1988-89, GB 2312-80; GB 1988-89, GBK — Taiwan: ASCII, Big Five; CNS 5205-1989, CNS 11643-1992 — Hong Kong: ASCII, Big Five with Hong Kong extension — Japan: JIS X 0201-1997, JIS X 0208:1997, JIS X 0212-1990 — South Korea: KS X 1003:1993, KS X 1001:1992, KS X 1002:1991 — North Korea: ASCII (?), KPS 9566-97 — Vietnam: TCVN 5712:1993, TCVN 5773:1993, TCVN 6056:1995 • Common CJKV encodings — Locale-independent: EUC-*, ISO-2022-* — Locale-specific: GBK, Big Five, Big Five Plus, Shift-JIS, Johab, Unified Hangul Code — Other: UCS-2, UCS-4, UTF-7, UTF-8, -

Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: From

al Ab gic no lo rm o a h l i c t y i e s s Ogawa et al., J Psychol Abnorm Child 2014, 3:3 P i Journal of Psychological Abnormalities n f o C l DOI: 10.4172/2329-9525.1000126 h a i n l d ISSN:r 2329-9525 r u e o n J in Children Research Article Open Access Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: from the Viewpoint of the Japanese Feature Shino Ogawa1*, Miwa Fukushima-Murata2, Namiko Kubo-Kawai3, Tomoko Asai4, Hiroko Taniai5 and Nobuo Masataka6 1Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan 2Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 3Faculty of Psychology, Aichi Shukutoku University, Aichi, Japan 4Nagoya City Child Welfare Center, Aichi, Japan 5Department of Pediatrics, Nagoya Central Care Center for Disabled Children, Aichi, Japan 6Section of Cognition and Learning, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Aichi, Japan Abstract This study identified the individual differences in the effects of Japanese Dyslexia. The participants consisted of 12 Japanese children who had difficulties in reading and writing Japanese and were suspected of having developmental disorders. A test battery was created on the basis of the characteristics of the Japanese language to examine Kana’s orthography-to-phonology mapping and target four cognitive skills: analysis of phonological structure, letter-to-sound conversion, visual information processing, and eye–hand coordination. An examination of the individual ability levels for these four elements revealed that reading and writing difficulties are not caused by a single disability, but by a combination of factors. -

Japanese Language and Culture

NIHONGO History of Japanese Language Many linguistic experts have found that there is no specific evidence linking Japanese to a single family of language. The most prominent theory says that it stems from the Altaic family(Korean, Mongolian, Tungusic, Turkish) The transition from old Japanese to Modern Japanese took place from about the 12th century to the 16th century. Sentence Structure Japanese: Tanaka-san ga piza o tabemasu. (Subject) (Object) (Verb) 田中さんが ピザを 食べます。 English: Mr. Tanaka eats a pizza. (Subject) (Verb) (Object) Where is the subject? I go to Tokyo. Japanese translation: (私が)東京に行きます。 [Watashi ga] Toukyou ni ikimasu. (Lit. Going to Tokyo.) “I” or “We” are often omitted. Hiragana, Katakana & Kanji Three types of characters are used in Japanese: Hiragana, Katakana & Kanji(Chinese characters). Mr. Tanaka goes to Canada: 田中さんはカナダに行きます [kanji][hiragana][kataka na][hiragana][kanji] [hiragana]b Two Speech Styles Distal-Style: Semi-Polite style, can be used to anyone other than family members/close friends. Direct-Style: Casual & blunt, can be used among family members and friends. In-Group/Out-Group Semi-Polite Style for Out-Group/Strangers I/We Direct-Style for Me/Us Polite Expressions Distal-Style: 1. Regular Speech 2. Ikimasu(he/I go) Honorific Speech 3. Irasshaimasu(he goes) Humble Speech Mairimasu(I/We go) Siblings: Age Matters Older Brother & Older Sister Ani & Ane 兄 と 姉 Younger Brother & Younger Sister Otooto & Imooto 弟 と 妹 My Family/Your Family My father: chichi父 Your father: otoosan My mother: haha母 お父さん My older brother: ani Your mother: okaasan お母さん Your older brother: oniisanお兄 兄 さん My older sister: ane姉 Your older sister: oneesan My younger brother: お姉さ otooto弟 ん Your younger brother: My younger sister: otootosan弟さん imooto妹 Your younger sister: imootosan 妹さん Boy Speech & Girl Speech blunt polite I/Me = watashi, boku, ore, I/Me = watashi, washi watakushi I am going = Boku iku.僕行 I am going = Watashi iku く。 wa. -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets............................................................................................................. -

Media Pustikelin London, 2001

Media Pustikelin London, 2001. European Centre for War Peace and the News Media dzutimasa khatar i Evropaki Kulturani Fondacia thaj o OSI editoro Milica Pesic lakhavnenda Lesley Abdela and Tim Symonds Eyecatcher Training INKERIMATA 1 TRANSLATORESKI VORBA 3 jekhto kotor SAR TE VAZDES EFEKTIVNE MEDIAKE RELACII 4 dujto kotor INTERJU ANDI TELEVIZIA THAJ ANDO RADIO 10 trito kotor SAR TE KERES ZURALI KAMPANJA E MEDIASA ANDO VAST 15 shtarto kotor E VAZHNE DZENENGO XUTERIPEN 22 pandzto kotor LILA E EDITORESKE,LILA E PRESSAKE tmd. 23 appendikso MEDIA RELACIENGI BUTJI ASTARDINDOS, tmd. 32 LAV E LAKHAVNENDAR 39 ECWPNM 39 Media Pustikelin drago drabarno, E idea vash o Media Pustikelin avili ande jekh khatar mashkarthemutni konfer- encia vash e Romane zhurnalisti thaj Romane Khetanimatange Sherutne, kerdo khatar o Open Society Institute (Budapest) ando Ohrid, Macedonia, februari, 1999. Diskussie mashkar e maj but sar 80 konferenciake dzene khatar 20 Evropake thema dine i vorba, ke o post-kommunisto vaxt na lokharel e Romengi situacia, ba shol le ando maj pharo trajo. Maj agressivo rassizmo resel len, anglikrisipen thaj diskriminacia. E butipnaski, gadzikani media bari rola sikavdas (thaj vi sikavel) ando kado processo te del stereotipikano sikavipe pe e Roma, butivar bi direktno kontakto e romane populaciasa. E diskussia ando Ohrid vi kodo svato phuterdas ke ando divesutno trajo naj but direktno kontakto mashkar e Roma thaj i gadzikani populacia. Misalake, jekh rodipe, so kerdas o Roma Press Centro ando Budapest, kasko sherutno sas andi konferencia, sikavdas ke e maj but rakle nivar na maladjon e romane sikljar- nenca andi shkola. Kado si mamuj o fakto, ke buteder sar 10% mashkar e cha- vorra ande 900 elementarne shkoli si romane sikle ando Ungriko Them. -

Like Mother, Like Daughters Kerr County I Hunting: Sisters, Mother Run West Kerr Ranch

Like mother, like daughters Kerr County I Hunting: Sisters, mother run West Kerr Ranch By Thomas Phillips Times Sports Design Editor thomas.ph [email protected] The pickup eases to a stop, and Ashley Kana peers into the brush outside. She grew up at the West Kerr Ranch and lives and works here full time now. She knows just about every bush, rock and shadow. This time, what has caught her eye is alive: A small group of elk shuffles Thomas Phillips/Times Sports Design Editor,[email protected] amidst cedar a few dozen yards away. Ashley Kana stands on a deck at her family's West Kerr Ranch. Ashley, The cows nervously trot off, and a her sister, Kelcie, and mother, Barbara, manage the 1O,SOO-acrespread . , lone bull tries to hold his ground but and guide hunters for white-tailed deer and exotics. relents to follow his harem. The West Kerrpresents so many in- fallow, Aoudad sheep, elk and black made since 1luIl's purchase, Ashley ~vt teresting angles. buck antelope. The exotics, except for Kana said. • Winner of the statewide Excel- the elk, carne with the property when 1luIl managed the West Kerr for lence in Range Management and Lone Barbara Kana's father,' Bob Trull, livestock. cattle and goats decimated Star Land Steward awards; bought it from the YO - legendary the vegetation, and in 1990 Barbara • A massive, 1O,SOO-acrtracte split for its exotics - in 1976. received permission to manage 2,500 offfrom the YORanch; The elk were introduced later, and • Run by two sisters and their no other exotic additions have been mother.