Spirited Sexuality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of the Séance: the Scientific Theory of the Spiritualist Movement in Victorian America

1 Hannah Gramson Larry Lipin HIST 491 March 6, 2013 The Science of the Seance: The Scientific Theory of the Spiritualist Movement in Victorian America In 1869, twenty one years after the first “spirit rappings” were heard in the bedroom of two young girls in upstate New York, a well-known Spiritualist medium by the name of Emma Hardinge Britten wrote a book that chronicled the first two decades of a religion she characterized as uniquely American, and what made this religion exceptional was its basis in scientific theory. “[We] are not aware of any other country than America,” Britten claimed, “where a popular religion thus appeals to the reason and requires its votaries to do their own thinking, or of any other denomination than 'American Spiritualists' who base their belief on scientific facts, proven by living witnesses.”1 Britten went on to claim that, as a “unique, concrete, and...isolated movement,” Spiritualism demanded “from historic justice a record as full, complete, and independent, as itself.”2 Yet, despite the best efforts of Spiritualism's followers to carve out a place for it alongside the greatest scientific discoveries in human history, Spiritualism remains a little understood and often mocked religion that, to those who are ignorant 1 Emma Hardinge Britten, Modern American Spiritualism: A Twenty Years' Record of the Communion Between Earth and the World of Spirits,(New York, 1869) 2 Britten, Modern American Spiritualism 2 of it, remains a seemingly paradoxical movement. Although it might be difficult for some to comprehend today, prior to the Civil War, religion and science were not considered adversaries by any means, but rather, were understood to be traveling down a shared path, with ultimately the same destination. -

The History Spiritualism

THE HISTORY of SPIRITUALISM by ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, M.D., LL.D. former President d'Honneur de la Fédération Spirite Internationale, President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science Volume One With Seven Plates PSYCHIC PRESS LTD First edition 1926 To SIR OLIVER LODGE, M.S. A great leader both in physical and in psychic science In token of respect This work is dedicated PREFACE This work has grown from small disconnected chapters into a narrative which covers in a way the whole history of the Spiritualistic movement. This genesis needs some little explanation. I had written certain studies with no particular ulterior object save to gain myself, and to pass on to others, a clear view of what seemed to me to be important episodes in the modern spiritual development of the human race. These included the chapters on Swedenborg, on Irving, on A. J. Davis, on the Hydesville incident, on the history of the Fox sisters, on the Eddys and on the life of D. D. Home. These were all done before it was suggested to my mind that I had already gone some distance in doing a fuller history of the Spiritualistic movement than had hitherto seen the light - a history which would have the advantage of being written from the inside and with intimate personal knowledge of those factors which are characteristic of this modern development. It is indeed curious that this movement, which many of us regard as the most important in the history of the world since the Christ episode, has never had a historian from those who were within it, and who had large personal experience of its development. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/02/2021 09:06:47AM Via Free Access 90 Bridget Bennett Serious Scholarship That Has Been Done on Spiritualism to Date

5 Crossing over: spiritualism and the Atlantic divide Bridget Bennett A joke has it that spiritualists first crossed the water in order to get to the other side. Despite its obvious shortcomings, it does suggest a more serious imperative: the investigation of how reading nineteenth-century spiritualism within a transatlantic context might be a highly revelatory activity, might indeed reveal something more interesting than we have hitherto considered about what crossing the Atlantic meant to spiritual- ists. Nineteenth-century spiritualism is routinely described as a phenom- enon that originated in the United States and spread first across the Atlantic and then world-wide. In this essay I will argue that a transatlan- tic focus challenges existing orthodoxies and suggests new areas of inves- tigation. Yet in describing this agenda for reading spiritualism I am conscious that this chapter asks more questions than it answers (and may, at times, seem to raise issues and give examples only to move elsewhere). Though many American and British spiritualists were more interested in the site of the seance, and the revelations it might contain, rather than its cultural origins, the same cannot be said for many historians of spiri- tualism. A number of historians have argued that spiritualism emerged in America as a discrete cultural phenomenon which needs to be read within its American context in order to make sense of its myth of origin – the ‘Rochester rappings’ of 1848. In such interpretations, American spiritual- ism is read as a culturally specific form that arises from a number of local geographical, cultural and political factors.1 Such an approach, however, does not sufficiently account for the complexities of spiritualism’s inher- itance; it does not consider the heterogeneity of a movement that draws from both sides of the Atlantic, and from European Christian traditions as well as Native American religious practices and, crucially, from the religious beliefs of slaves. -

Spiritualism and Possession

Moshe Sluhovsky. Believe Not Every Spirit: Possession, Mysticism, and Discernment in Early Modern Catholicism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. 384 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-226-76282-1. Reviewed by Marc R. Forster (Department of History, Connecticut College) Published on H-HRE (February, 2008) Spiritualism and Possession Moshe Sluhovsky has wrien an excellent study of ese forms of “passive interiority” were however possession and mysticism in early modern European not just for women and were widely practiced among Catholicism. His elegantly wrien and clearly argued Catholics, including, for example, the Jesuits. However, book, Believe Not Every Spirit, points scholars in some the official church also always considered them suspect. new directions in understanding the meaning of demonic Sluhovsky explains in detail the theological debates that possession. Most importantly, Sluhovsky links cases of aempted to draw lines between acceptable and unac- demonic possession to spiritual developments in Catholi- ceptable (possibly heretical) forms of mysticism. He cism, developments that caused considerable tension and points out, in addition, that mystical practices were in- even confusion for church leaders, while opening both creasingly considered feminine. French mystics of this opportunities and dangers for individual believers, espe- type were sometimes called femmelees, people who cially women, who were inclined toward mystical and lacked the reason and control for proper piety. More sig- interiorized spirituality. nificant for the argument of this book, Sluhovsky empha- Sluhovsky presents a clear narrative of the history of sizes that both practitioners and church leaders consid- diabolic possession. is story is perhaps not surpris- ered the practices of passive interior mysticism fraught ing and mirrors in many ways developments in witch with the danger of diabolical possession. -

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

THE MEDIUMSHIP of ARNOLD CLARE Leader of the Trinity of Spiritual Fellowship

THE MEDIUMSHIP OF ARNOLD CLARE Leader of the Trinity of Spiritual Fellowship by HARRY EDWARDS Captain, Indian Army Reserve of Officers. Lieutenant, Home Guard. Parliamentary Candidate North Camberwell 1929 and North-West Camberwell 1936. London County Council Candidate 1928, 1931, 1934, 1937. Leader of the Balham Psychic Research Society. Author of ‘The Mediumship of Jack Webber’ First Published by: THE PSYCHIC BOOK CLUB 144 High Holborn, London, W.C. 1 FOREWORD Apart from the report by Mr. W. Harrison of the early development of Mr. Arnold Clare's mediumship, the descriptions of the séances, the revelations of Peter and the writing of this book took place during the war years 1940-41. As enemy action on London intensified, the physical séances ceased and in the autumn of 1940 were replaced by discussion circles. The first few circles took place in the author's house before a company of about twenty people. It was soon appreciated that the intelligence (known as Peter), speaking through the entranced medium, was of a high order and worthy of reporting. So these large discussion groups gave way to a small circle held in the medium's house, attended by Mr. and Mrs. Clare, Mr. and Mrs. Hart, Mrs. Edwards and the author, an occasional visitor and with Mrs. W. B. Cleveland as stenographer. The procedure at these circles would be that, in normal white light, Mr. Clare would enter into a trance state. His Guide, Peter, taking control, would discourse upon the selected topic answering all questions fluently and without hesitation. Frequently, during these sittings, the air-raid sirens would be heard and the local anti- aircraft guns would be in action. -

A Glimpse at Spiritualism

A GLIMPSE AT SPIRITUALISM P.V JOITX J. BIRCH ^'*IiE term Spiritualism, as used by philosophical writers denotes the opposite of materialism., but it is also used in a narrower sense to describe the belief that the spiritual world manifests itself by producing in the physical world, effects inexplicable by the known laws of natural science. Many individuals are of the opinion that it is a new doctrine: but in reality the belief in occasional manifesta- tions of a supernatural world has probably existed in the human mind from the most primitive times to the very moment. It has filtered down through the ages under various names. As Haynes states in his book. Spirifttallsiii I'S. Christianity, 'Tt has existed for ages in the midst of heathen darkness, and its presence in savage lands has been marked by no march of progress, bv no advance in civilization, by no development of education, by no illumination of the mental faculties, by no increase of intelligence, but its acceptance has been productive of and coexistent with the most profound ignor- ance, the most barbarous superstitions, the most unspeakable immor- talities, the basest idolatries and the worst atrocities which the world has ever known."' In Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Greece and Rome such things as astrology, soothsaying, magic, divination, witchcraft and necromancy were common. ]\ loses gives very early in the history of the human race a catalogue of spirit manifestations when he said: "There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daugh- ter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch, or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a necromancer. -

Issue-05-9.Pdf

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO| • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD, biochemist president of ZOL James E- Oberg, science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York. NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Loren Pankratz. psychologist. Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro. science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ., Vancouver, B.C.. Canada Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist Univ. of Chicago Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Wallace Sampson. M.D.. clinical professor of medi California and professor of history of science, Harvard Univ. cine. Stanford Univ.. editor, Scientific Review of Susan Blackmore, Visiting Lecturer, Univ. of the Ray Hyman,' psychologist. -

Physiology Or Psychic Powers? William Carpenter and the Debate Over Spiritualism in Victorian Britain

Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences xxx (2014) 1e10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc Physiology or psychic powers? William Carpenter and the debate over spiritualism in Victorian Britain Shannon Delorme History of Science, University of Oxford, New College, Holywell Street, OX1 3BN Oxford, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: This paper analyses the attitude of the British Physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter (1813e1885) to Available online xxx spiritualist claims and other alleged psychical phenomena in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. It argues that existing portraits of Carpenter as a critic of psychical studies need to be refined so as to Keywords: include his curiosity about certain ‘unexplained phenomena’, as well as broadened so as to take into Spiritualism account his overarching epistemological approach in a context of theological and social fluidity within Psychical research nineteenth-century British Unitarianism. Carpenter’s hostility towards spiritualism has been well Neurophysiology documented, but his interest in the possibility of thought-transference or his secret fascination with the Unitarianism ’ William B. Carpenter medium Henry Slade have not been mentioned until now. This paper therefore highlights Carpenter s Religious naturalism ambivalences and focuses on his conciliatory attitude towards a number of heterodoxies while sug- gesting that his Unitarian faith offers the keys to understanding his unflinching rationalism, his belief in the enduring power of mind, and his effort to resolve dualisms. Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. When citing this paper, please use the full journal title Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 1. -

Osu1199254932.Pdf (640.26

FROM MUSE TO MILITANT: FRANCOPHONE WOMEN NOVELISTS AND SURREALIST AESTHETICS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mary Anne Harsh, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Danielle Marx-Scouras, Advisor Professor Karlis Racevskis ______________________________ Advisor Professor Sabra Webber French and Italian Graduate Program ABSTRACT In 1924, André Breton launched the Surrealist movement in France with his publication of Manifeste du surréalisme. He and his group of mostly male disciples, prompted by the horrors of World War I, searched for fresh formulas for depicting the bizarre and inhumane events of the era and for reviving the arts in Europe, notably by experimenting with innovative practices which included probing the unconscious mind. Women, if they had a role, were viewed as muses or performed only ancillary responsibilities in the movement. Their participation was usually in the graphic arts rather than in literature. However, in later generations, francophone women writers such as Joyce Mansour and Suzanne Césaire began to develop Surrealist strategies for enacting their own subjectivity and promoting their political agendas. Aside from casual mention, no critic has formally investigated the surreal practices of this sizeable company of francophone women authors. I examine the literary production of seven women from three geographic regions in order to document the enduring capacity of surrealist practice to express human experience in the postcolonial and postmodern era. From the Maghreb I analyze La Grotte éclatée by Yamina Mechakra and L'amour, la fantasia by Assia Djebar, and from Lebanon, L'Excisée by Evelyne Accad. -

PSYPIONEER JOURNAL Volume 7, No 8: August 2011

PSYPIONEERF JOURNAL Founded by Leslie Price Edited by Archived by Paul J. Gaunt Garth Willey EST 2004 VolumeAmalgamation 7, No 8:of Societies August 2011 Evan Powell the Welsh Physical Medium - Psychic Science 235 Origins and Editorship of Light – Paul J. Gaunt 243 The Jubilee of Light – Light 244 Some reminiscences of “Light” and the L.S.A. – Light 245 The late Mr. Henry Withall – Dawson Rogers 246 Decease of Mr. Henry Withall – Light 248 Transition of Mrs. Withall – Light 250 Hannen Swaffer “Swaff” 251 Who’s Who in the S.N.U. Hannen Swaffer, esq., Honorary President S.N.U – The National Spiritualist 252 How I Became a Spiritualist (Hannen Swaffer) – The National Spiritualist 254 Facts from the History of Miss Wood’s Development as a Medium by Mrs. Mould – Medium and Daybreak 257 Some books we have reviewed 265 How to obtain this Journal by email 266 ============================ 234 Evan Powell (1881-1958) In the last issue of Psypioneer we published “Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Evan Powell”.1 We continue in this issue with Evan Powell’s earlier life and his mediumship as recorded at the British College of Psychic Science (BCPS);2 this is published below. In the next issue we will conclude our research into this once well-known and respected Spiritualist medium. Paul J. Gaunt. 1 See Psypioneer Volume 7, No.7:—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Evan Powell – Paul J. Gaunt; and Evan Powell’s Mediumship – Leslie Curnow, pages 219-227:— http://www.woodlandway.org/PDF/PP7.7July2011.pdf 2 See Psypioneer Volume 7, No.2:—Whatever happened to the British College? - The International Institute for Psychic Investigation (IIPI), pages 35-46:—http://woodlandway.org/PDF/PP7.2February2010.pdf 235 EVAN POWELL THE WELSH PHYSICAL MEDIUM Psychic Science:—3 By the Hon. -

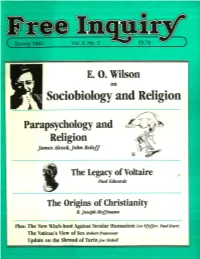

Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701

LmAA_____., Fir ( Spring 1985 E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Parapsychology and Religion James Alcock, John Beloff The Legacy of Voltaire Paul Edwards The Origins of Christianity R. Joseph Hoffmann Plus: The New Witch-hunt Against Secular Humanism Leo Pfeffer, Paul Kurtz The Vatican's View of Sex Robert Francoeur Update on the Shroud of Turin joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701 VOL. 5, NO. 2 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 EDITORIALS 8 ON THE BARRICADES ARTICLES 10 Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell 11 The Vatican's View of Sex: The Inaccurate Conception Robert T. Francoeur 15 An Interview with E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Jeffrey Saver RELIGION AND PARAPSYCHOLOGY 25 Parapsychology: The "Spiritual" Science James E. Alcock 36 Science, Religion and the Paranormal John Beloff 42 The Legacy of Voltaire (Part I) Paul Edwards 50 The Origins of Christianity: A Guide to Answering Fundamentalists R. Joseph Hoffmann BOOKS 57 Humanist Solutions Vern Bullough 58 Doomsday Environmentalism and Cancer Rodger Pirnie Doyle 59 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Gordon Stein, Lee Nisbet, Steven L. Mitchell, Doris Doyle Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Contributing Editors: Lionel Abel, author, critic, SUNY at Buffalo; Paul Beattie, president, Fellowship of Religious Humanists; Jo-Ann Boydston, director, Dewey Center; Laurence Briskman, lecturer, Edinburgh University, Scotland; Vern Bullough, historian, State University of New York College at Buffalo; Albert Ellis, director,