The 'World of the Infinitely Little'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stage Is Set

The Stage Is Set: Developments before 1900 Leading to Practical Wireless Communication Darrel T. Emerson National Radio Astronomy Observatory1, 949 N. Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721 In 1909, Guglielmo Marconi and Carl Ferdinand Braun were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy." In the Nobel Prize Presentation Speech by the President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences [1], tribute was first paid to the earlier theorists and experimentalists. “It was Faraday with his unique penetrating power of mind, who first suspected a close connection between the phenomena of light and electricity, and it was Maxwell who transformed his bold concepts and thoughts into mathematical language, and finally, it was Hertz who through his classical experiments showed that the new ideas as to the nature of electricity and light had a real basis in fact.” These and many other scientists set the stage for the rapid development of wireless communication starting in the last decade of the 19th century. I. INTRODUCTION A key factor in the development of wireless communication, as opposed to pure research into the science of electromagnetic waves and phenomena, was simply the motivation to make it work. More than anyone else, Marconi was to provide that. However, for the possibility of wireless communication to be treated as a serious possibility in the first place and for it to be able to develop, there had to be an adequate theoretical and technological background. Electromagnetic theory, itself based on earlier experiment and theory, had to be sufficiently developed that 1. -

Spiritualism and Sir Oliver Lodge

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 SPIRITUALISM AND SIR OLIVER LODGE PREFACE SIR OLIVER LODGE'S book Raymond was sent to me with a request that I would examine and review it. I found it impossible to do so. The sorrow of a bereaved mother is no fit matter for discussion by strangers in the public press. But the book revealed to me such an astounding mental attitude on the part of its author, that I sent for a previous work of his, The Survival of Man, to discover on what ground he, a professor of a certain branch of physical science, and the Principal of a University, speaking with the authority conferred by his occupancy of these positions, could make the assumptions that he does, and promulgate urbi et orbi such extraordinary doctrines. I have been engaged for some forty years in the study of the vagaries of the human mind in health and in disease, and am not easily surprised by witnessing new vagaries ; but I must confess that The Survival of Man did surprise me. Upon inquiry I found that the doctrines and prac- tices therein advocated have attained a very wide vogue. It may almost be said that they are become the rage. There is nothing very surprising in this, for the pursuit of the occult has for from time to time has ages prevailed ; its have spread and become fashionable ; pretensions been it to some exposed ; and has died down, only reappear years afterwards, when the exposure was forgotten. -

Henry Handel Richardson, a Secret Life – by Dr Barbara Finlayson

Henry Handel Richardson, a Secret Life – a talk given by Dr Barbara Finlayson at the Bendigo Philosopher’s Group on July 2, 2018 The background music are songs to which Henry Handel Richardson (HHR mainly from now on) wrote the music, some whilst she was at school, others as a music student at Leipzig. That she wrote music is not well known as was her deep involvement in Spiritualism, the subject of my talk. Firstly though, I shall give a very, very, potted summary about this author Henry Handel Richardson, the nom de plume of Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson. She was born on the 3rd January 1870 in East Melbourne, the eldest daughter of Dr Walter Richardson and his wife Mary. The family lived in various Victorian towns, as well as Melbourne itself during HHR’s childhood and youth. These included Chiltern, Queenscliff, Koroit, and Maldon after her father’s death. Her mother took the family to Europe in 1888 to enable HHR and her sister Lill to continue her musical studies at the Leipzig Conservatorium. HHR married George Robertson who became chair at the University of London and they moved to that city 1903. She published her first novel, Maurice Guest in 1908 and that is when she adopted her pseudonym. (I have included a list of her writing in the hand out.) The best known are The Getting of Wisdom and The Fortunes of Richard Mahony. She died in 1946, aged 76. In Dorothy Green’s book about Henry Handel Richardson, Ulysses Bound, she said, ‘Richardson’s life-long adherence to Spiritualism is a fact which has largely been ignored.’ This book was first published in 1973, and HHR’s involvement in Spiritualism was largely ignored until 1996 when 2 events occurred. -

Osu1199254932.Pdf (640.26

FROM MUSE TO MILITANT: FRANCOPHONE WOMEN NOVELISTS AND SURREALIST AESTHETICS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mary Anne Harsh, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Danielle Marx-Scouras, Advisor Professor Karlis Racevskis ______________________________ Advisor Professor Sabra Webber French and Italian Graduate Program ABSTRACT In 1924, André Breton launched the Surrealist movement in France with his publication of Manifeste du surréalisme. He and his group of mostly male disciples, prompted by the horrors of World War I, searched for fresh formulas for depicting the bizarre and inhumane events of the era and for reviving the arts in Europe, notably by experimenting with innovative practices which included probing the unconscious mind. Women, if they had a role, were viewed as muses or performed only ancillary responsibilities in the movement. Their participation was usually in the graphic arts rather than in literature. However, in later generations, francophone women writers such as Joyce Mansour and Suzanne Césaire began to develop Surrealist strategies for enacting their own subjectivity and promoting their political agendas. Aside from casual mention, no critic has formally investigated the surreal practices of this sizeable company of francophone women authors. I examine the literary production of seven women from three geographic regions in order to document the enduring capacity of surrealist practice to express human experience in the postcolonial and postmodern era. From the Maghreb I analyze La Grotte éclatée by Yamina Mechakra and L'amour, la fantasia by Assia Djebar, and from Lebanon, L'Excisée by Evelyne Accad. -

Palmistry: Science Or Hand-Jive?

the Skeptical Inquirer PALMISTRY: SCIENCE OR HAND-JIVE? SRI GELLER TEST / LOCHNESS TREE TRUNK / A PILOT'S UFO WHY SKEPTICS ARE SKEPTICAL VOL. VII No. 2 WINTER 191 Published by the Committee lor the Scientific Investigation of :of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board George Abell. Martin Gardner. Ray Hyman. Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge. John Boardman, Milbourne Christopher. John R. Cole. Richard de Mille, C.E.M. Hansel, E.C. Krupp. James Oberg. Robert Sheaffer. Assistant Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Production Editor Belsy Offermann. Business Manager Lynette Nisbet. Office Manager Mary Rose Hays Staff Idelle Abrams. Judy Hays. Alfreda Pidgeon Cartoonist Rob Pudim The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher. State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Executive Director; philosopher, Medaille College. Fellows of the Committee: George Abed, astronomer, UCLA; James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, chemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist. SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Bart J. Bok, astronomer. Steward Observatory, Univ. of Arizona; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; Milbourne Christopher, magician, author; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, European Editor, Omni; Paul Edwards, philosopher. Editor, Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Charles Fair, author, Antony Flew, philosopher, Reading Univ., O.K.: Kendrick Frazier, science writer. Editor. THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER; Yves Galifret, Exec. Secretary, I'Union Rationaliste; Martin Gardner, author. -

Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701

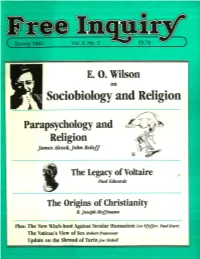

LmAA_____., Fir ( Spring 1985 E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Parapsychology and Religion James Alcock, John Beloff The Legacy of Voltaire Paul Edwards The Origins of Christianity R. Joseph Hoffmann Plus: The New Witch-hunt Against Secular Humanism Leo Pfeffer, Paul Kurtz The Vatican's View of Sex Robert Francoeur Update on the Shroud of Turin joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701 VOL. 5, NO. 2 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 EDITORIALS 8 ON THE BARRICADES ARTICLES 10 Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell 11 The Vatican's View of Sex: The Inaccurate Conception Robert T. Francoeur 15 An Interview with E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Jeffrey Saver RELIGION AND PARAPSYCHOLOGY 25 Parapsychology: The "Spiritual" Science James E. Alcock 36 Science, Religion and the Paranormal John Beloff 42 The Legacy of Voltaire (Part I) Paul Edwards 50 The Origins of Christianity: A Guide to Answering Fundamentalists R. Joseph Hoffmann BOOKS 57 Humanist Solutions Vern Bullough 58 Doomsday Environmentalism and Cancer Rodger Pirnie Doyle 59 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Gordon Stein, Lee Nisbet, Steven L. Mitchell, Doris Doyle Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Contributing Editors: Lionel Abel, author, critic, SUNY at Buffalo; Paul Beattie, president, Fellowship of Religious Humanists; Jo-Ann Boydston, director, Dewey Center; Laurence Briskman, lecturer, Edinburgh University, Scotland; Vern Bullough, historian, State University of New York College at Buffalo; Albert Ellis, director, -

Magicians on the Paranormal: an Essay with a Review of Three Books

Magicians on the Paranormal: An Essay with a Review of Three Books GEORGE P. HANSEN’ ABSTRACT: Conjurors have written books on the paranormal since the 1500s. A number of these books are listed and briefly discussed herein, including those of both skeptics and proponents. Lists of magicians on both sides of the psi controversy are provided. Although many people perceive conjurors to be skeptics and debunkers, some of the most prominent magicians in history have endorsed the reality of psychic phenomena. The reader is warned that conjurors’ public statements asserting the reality of psi are sometimes difficult to eval- uate. Some mentalists publicly claim psychic abilities but privately admit that they do not believe in them; others privately acknowledge their own psychic experiences. Thme current books are fully reviewed: EntraSensory Deception by Henry Gordon (1987), Forbidden Knowledge by Bob Couttie (1988), and Secrets of the Supernatural by Joe Nickel1 (with Fischer, 1988). The books by Gordon and Couttie contain serious errors and are of little value, but the work by Nickel1 is a worthwhile contribution, though only partially concerned with psi. Magicians have been involved with paranormal controversies for cen- turies, and their participation has been far more complex and multifaceted than the usual stereotype of magicians as skeptical debunkers. In this paper, I review three fairly recent skeptical books by magicians, but before these are discussed, some remarks are in order concerning conjurors’ in- volvement with psi and psi research because there has been little useful discussion of the topic in the parapsychology literature.’ It is important to understand this background because several magicians have had an impact on scientists’ and the general public’s perception of psychical research, and some have played a major role in the modem-day skeptical movement (Hansen, 1992). -

Modernscience

386 Book Reviews Modern Science Annette Müllberger (ed.) Los límites de la ciencia. Espiritismo, hipnotismo y el estudio de los fenómenos para- normales (1850–1930). Madrid: Consejo superior de investigaciones científicas, 2016, 346 pp., 30€, ISBN: 978-84-00-10053-7. In the last few years, the history of science has been showing a particular inter- est in the field of psychical research, metapsychics and all that today is defined as parapsychology. The works of historians of science like Ruth Brandon, John Cerullo, Alex Owen and most recently those of Sofie Lachapelle, Régine Plas, Christine Blondel, Heather Wolffram and Andreas Sommer, only to name a few, have overcome the initial historians’ mistrust towards to this complex and var- iegated range of phenomena, thus considering it as a proper epistemic object. Less rigid definitions of “science” and “rationality” have been provided, which have called into question the structure of an allegedly real and objective knowl- edge. Even the debate among those who declared themselves interested in rethinking and expanding the limits of science and those who, on the contrary, were claiming that the study of the paranormal should be left out from the def- inition of “science”, has become the subject of these investigations of historical nature. Science is indubitably the result of a complex process. The outcome of this process is a totality of statements about reality that calls for trust and faith. Science creates convictions and beliefs. Spiritualism wished to generate convictions too, and the believer who welcomed such convictions found itself part of the epistemological process of creation of belief, in addition to being receptor of the “truths” in question. -

Dalrev Vol1 Iss2 Pp151 159.Pdf (886.7Kb)

SPIRITUALISM AND IMMORTALITY j. M. SHAW Professor of Systematic Theology, Pine Hill College N a recent widely-read book entitled The Road to Endor I an intensely interesting account is given of how two British officers won their way to freedom from a Turkish prisoner-of-war camp by the use of methods usually described as "spiritualistic." The attitude of the author towards the phenomena so described may already be guessed from the title of his work, borrowed as it is from Mr. Rudyard Kipling's satiric lines: Oh, the road to En-dor is the oldest road And the craziest road of all ! Straight it runs to the Witch's abode, AB it did in the days of Saul, And nothing is changed of the sorrow in store For such as go down on the road to En-dor!- It is thus explicitly set forth in the Preface (p. ix): "If this book saves one widow from lightly trusting the exponents of a creed that is crass and vulgar and in truth nothing better than a confused materialism, or one bereaved mother from preferring the unwhole some excitement of the seance and the trivial babble of a hired trickster to the healing power of moral and religious reflection on the truths that give to human life its stability and worth, then the miseries and sufferings through which we passed in our struggle for freedom will indeed have had a most ample reward." I On the other hand, in an even more widely-read publication of a year or two earlier the distinguished author excuses himself in his Preface for his seeming obtrusion of private family affairs and revelations upon the attention of the general public, on the ground of the comfort the facts narrated are calculated to afford to those who like himself have suffered bereavement through the Great War. -

Newspaper, Spiritualism, and British Society, 1881 - 1920

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2009 'Light, More Light': The 'Light' Newspaper, Spiritualism, and British Society, 1881 - 1920. Brian Glenney Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Glenney, Brian, "'Light, More Light': The 'Light' Newspaper, Spiritualism, and British Society, 1881 - 1920." (2009). All Theses. 668. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "LIGHT, MORE LIGHT”: The “Light” Newspaper, Spiritualism and British Society, 1881-1920. A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters in History by Brian Edmund Glenney December, 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Michael Silvestri, Committee Chair Dr. Alan Grubb Dr. Megan Taylor Shockley i ABSTRACT This thesis looks at the spiritualist weekly Light through Late Victorian, Edwardian, and World War I Britain. Light has never received any extended coverage or historical treatment yet it was one of the major spiritualist newspapers during this part of British history. This thesis diagrams the lives of Light ’s first four major editors from 1881 till the end of World War I and their views on the growth of science, God, Christ, evolution, and morality. By focusing on one major spiritualist newspaper from 1881 till 1920, this thesis attempts to bridge the gap in spiritualist historiography that marks World War I as a stopping or starting point. -

Christopher Hartney

OF SEANCE AND SURREALISM, POETRY AND CRISIS Christopher Hartney When asked by a bureaucrat what purpose poetry served a nation, A. D. Hope quipped that it justifies its existence. This might seem an exuberant claim, but in conservative titnes it is sometimes hard to discern the value to society of the poetic quest. 1 This paper is an examination of that period between the Great War and the onset of the Great Depression when poetry became a centre of certainty in the lives of those lost in the maelstrom of the times. It may be a broad comparison to draw, but I have chosen to look at Vietnam and its colonial master of the period, France. It is in the t\venties that these two nations became the focal point for two highly influential social movements that sought to revi vify not just national existence but the human spirit. In France this revitalisation was effected via the movement kno\vn as surrealism. Clearly it was a secular movement, and yet its poetic quest had much in common \vith religious developments bursting onto the scene in Vietnam at the same time; in particular a new religious movement called Caodaism. The twenties were crucible years; after the Great War, many assumptions about life and civilisation had to be rethought. In France, Surrealism would create a vital social space \vithin which this rethinking could take place. Artistically, Surrealism's primary source of influence was Dada, but Surrealists also couched the movement's heritage I For example, a current indication of the place of poetry in Australia, Rosanna 1Y1cGlone-Healy writes in the Sydney fl;lorning Herald, 29-30 Septelnber 200 I (Spectrum 6) 'The support for literature is smalL and the place of poetry in the national psyche is negligible.' 355 CHRIS HARTNEY as coming from the growing scientific tradition of psychoanalysis. -

Prophetess of the Spirits: Mother Leaf Anderson and the Black Spiritual Churches of New Orleans

SIXTEEN Prophetess of the Spirits Mother Leaf Anderson and the Black Spiritual Churches of New Orleans Yvonne Chireau Mother Leaf Anderson, a thirty-two-year-old missionary, preacher, and proph etess, went to New Orleans, Louisiana, in 19 ig to establish a church that would reflect her distinctive vision of sacred reality. In 1927, when she died, she left a legacy of women’s leadership and spiritual innovation that had transformed the religious landscape of the city for both blacks and whites. Anderson, a woman of African and Native American ancestry, founded a religion that would carry her signature into the present day. Leaf Anderson’s role in the formation of the New Orleans black Spiritual churches reveals the unusual and complex cultural configurations that she embodied in both her life and her ministry. The ways that she redefined gender and religious empower ment for women in the Spiritual tradition influenced all who came after her. This essay considers gender and race as intersecting categories in its analy sis of the churches established by Anderson, a network of congregations that synthesized elements of Protestantism, Catholicism, nineteenth-century American spiritualism, and neo-African religions. My focus on African Amer ican women serves as a counterbalance to interpretations of religious his tory that fail to account for race, class, and gender as determinants of female subjectivity. The contrasting social and cultural realities for black and white women underscore the differences in the religious options that both groups have historically sought and chosen. The black Spiritual movement is one product of those differences.