Harry Hems and St Peter's Revelstoke, Noss Mayo, Devon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document For

South Hams Development Management Committee Title: Agenda Date: Wednesday, 15th March, 2017 Time: 10.00 am Venue: Council Chamber - Follaton House Full Members: Chairman Cllr Steer Vice Chairman Cllr Foss Members: Cllr Bramble Cllr Hodgson Cllr Brazil Cllr Holway Cllr Cane Cllr Pearce Cllr Cuthbert Cllr Rowe Cllr Hitchins Cllr Vint Interests – Members are reminded of their responsibility to declare any Declaration and disclosable pecuniary interest not entered in the Authority's Restriction on register or local non pecuniary interest which they have in any Participation: item of business on the agenda (subject to the exception for sensitive information) and to leave the meeting prior to discussion and voting on an item in which they have a disclosable pecuniary interest. Committee Kathy Trant, Specialist - Democratic Services 01803 861185 administrator: Page No 1. Minutes 1 - 10 To approve as a correct record and authorise the Chairman to sign the minutes of the meeting of the Committee held 15 February 2017. 2. Urgent Business Brought forward at the discretion of the Chairman; 3. Division of Agenda to consider whether the discussion of any item of business is likely to lead to the disclosure of exempt information; 4. Declarations of Interest Members are invited to declare any personal or disclosable pecuniary interests, including the nature and extent of such interests they may have in any items to be considered at this meeting; 5. Public Participation The Chairman to advise the Committee on any requests received from members of the public -

Puss in Boots

For the People of Modbury & Brownston Volume 18, Issue 233 September 2018 MODBURY WI - JANET WINS THE CUP Janet Thomas was the first winner of the trophy in the new WI Craft Class at this year’s Modbury Fruit and Produce Show. Janet submitted a bag she had woven in a complex checked pattern and made up herself, which was a real tour de force and a very worthy winner. Our new programme starts in September after an August meeting break and we will meet on the first Tuesday evening of the month from now on, which we hope will encourage new members as Friday evenings have proved problematic in the past. The next meeting will take place at 7.30pm on Tuesday, 4th September in the MARS Pavilion, Queen Elizabeth II Recreation Ground, Chatwell Lane, Modbury when the speaker will be hypotherapist Grace Jones from Elegant Thinking. In addition to our monthly meetings we have book, craft, walking and cinema going groups as well as visits to places of interest in the locality. Why not come along as a guest to the next meeting to see for yourself what Modbury WI has to offer? Please contact me at [email protected] if you would like to find out more. Rosemary Parker The Modbury Pantomime returns with Puss in Boots on 3, 4, 5 January 2019 Anyone interested in being: onstage, backstage, costume, music, singing, dancing ** Support or Star** Please come to an Open Meeting at 11:00 on Saturday 15 September in Modbury Memorial Hall Nigel & Felicity Guild look forward to seeing you then; and/or contact us any time: 20 Church Street Page 1 thebrownstongallery ANTHONY AMOS (1950 - 2010) Master Marine Artist 15 - 29 September art prints sculpture jewellery www.thebrownstongallery.co.uk I’ve got money 4 U Any person residing in Modbury Parish who is leaving school to start higher/further education or a training scheme is ENTITLED to a small, one off, grant from the Modbury Education Foundation Please apply by 1st October 2018. -

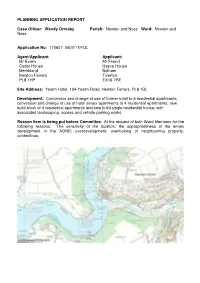

Newton and Noss Ward: Newton and Noss

PLANNING APPLICATION REPORT Case Officer: Wendy Ormsby Parish: Newton and Noss Ward: Newton and Noss Application No : 170607 0607/17/FUL Agent/Applicant: Applicant: Mr Evans Mr Friend Cedar House Hayne House Membland Bolham Newton Ferrers Tiverton PL8 1HP EX16 7RE Site Address: Yealm Hotel, 104 Yealm Road, Newton Ferrers, PL8 1BL Development: Conversion and change of use of former hotel to 6 residential apartments; conversion and change of use of hotel annex apartments to 4 residential apartments; new build block of 4 residential apartments and new build single residential house; with associated landscaping, access and vehicle parking works. Reason item is being put before Committee. At the request of both Ward Members for the following reasons: The sensitivity of the location; the appropriateness of the annex development in the AONB; overdevelopment; overlooking of neighbouring property, contentious. Recommendation: That delegated authority be given to the COP Lead Development Management, in consultation with the Chairman of Development Management Committee, to grant conditional approval subject to satisfactory completion of a section 106 agreement to secure the following: • Off-site contribution towards affordable housing: £122,710 • Education infrastructure: £49,322 (secondary school only) • Education transport: £9,291 • Early years education: £3,750 • Contribution of £14,441.35 towards improvements to play and sports facilities in Butts park, Newton Ferrers. • Contribution of £485.65 towards the Yealm Estuary Environmental Management -

Ivybridge Deanery Review Report January 2018

Ivybridge Deanery Review Report January 2018 Mrs Gillian Parker QPM, retired Chief Constable, Churchwarden of Holne with Huccaby The Revd Prebendary Nick Shutt LLM, Rector of the West Dartmoor Mission Community The Venerable Douglas Dettmer, Archdeacon of Totnes INTRODUCTION 4 IVYBRIDGE DEANERY 4 METHODOLOGY 5 FINDINGS 5 DEANERY 6 DEANERY SYNOD & DEANERY PASTORAL COMMITTEE 6 RECOMMENDATION 1 6 MISSION COMMUNITIES 6 PARISHES 7 WEMBURY 7 RECOMMENDATION 2 8 BRIXTON 8 RECOMMENDATION 3 9 YEALMPTON 9 RECOMMENDATION 4 10 NEWTON FERRERS 10 REVELSTOKE/NOSS MAYO 11 HOLBETON (AND ERMINGTON) 11 RECOMMENDATION 5 12 SPARKWELL 13 RECOMMENDATION 6 14 CORNWOOD 14 RECOMMENDATION 7 14 HARFORD 14 RECOMMENDATION 8 14 IVYBRIDGE 15 RECOMMENDATION 9 16 CLERGY PROVISION AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF PASTORAL REORGANISATION 17 2 IMPACT ON NEIGHBOURING PARISHES, DEANERIES, AND ARCHDEACONRIES 17 DEANERY IMPACT 17 RECOMMENDATION 10 18 DIOCESAN AND ARCHDEACONRY IMPACT 18 RECOMMENDATION 11 18 NEXT STEPS 18 TIMING 21 RECOMMENDATION 12 21 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 22 RECOMMENDATION 1 22 RECOMMENDATION 2 22 RECOMMENDATION 3 22 RECOMMENDATION 4 22 RECOMMENDATION 5 23 RECOMMENDATION 6 23 RECOMMENDATION 7 23 RECOMMENDATION 8 23 RECOMMENDATION 9 24 RECOMMENDATION 10 24 RECOMMENDATION 11 24 RECOMMENDATION 12 24 APPENDIX A – LETTER FROM THE BISHOP OF EXETER 25 APPENDIX B – INTERVIEWS AND MEETINGS & OTHER CORRESPONDENTS 27 APPENDIX C – 2018 COMMON FUND ASSESSMENT & PARTICIPANTS 29 APPENDIX D – COMMON FUND PAYMENTS 2017 31 3 Introduction The vision of the Diocese of Exeter is to be people who together are growing in prayer, making new disciples, and serving the people of Devon with joy. These aims are implicit in the following document and form the basis of its recommendations. -

Yealm Bioblitz Report Compressed.Pdf

Life on the Yealm Initiative Report on the first 6 months of activities Newton and Noss Environment Group Written by John Green & Chris McGimpsey “I saw several lines of children going to and from visits. They were all having a great time. There was a lovely sight under the tree outside on Friday when a lady was sat in a chair with 20 enthralled children around her.” Raymond Wergan , Yealm estuary, July 2018 Lee Bay Bioblitz 2017 Eggs of the Atlantic bobtail squid Sepiola atlantica Photo by Dave Fenwick The Life on the Yealm initiative With its seagrass beds, creeks, sea cliffs and ancient woodlands, the Yealm estuary is a haven for a diverse range of species. The Marine Biological Association of the UK (MBA) chose the estuary and the parish of Newton and Noss to host its 10th BioBlitz, as part of a local initiative to celebrate the area’s wildlife. The Life on the Yealm initiative has involved providing training and activities for school children, teachers and the local community. Steered by the interests and aspirations of local residents, events have been organised by the MBA with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, The Yealm Waterside Homes, the Royal Society of Biology and Plymouth Radio. The Yealm BioBlitz, held on 13th & 14th July, was the focal point for the initiative, enabling participants of all levels of expertise and ages to take part in a wide range of fun, educational and scientific data collection activities, which helped to identify and record the wide range of species living in the area. -

Dovecote House Dovecote House Membland, Newton Ferrers, PL8 1HP Village Centre 1 Mile Plymouth 10 Miles Exeter 43 Miles

Dovecote House Dovecote House Membland, Newton Ferrers, PL8 1HP Village Centre 1 mile Plymouth 10 miles Exeter 43 miles • Pretty South Hams Hamlet • Sought After Area • Large Historic Property with Character and Charm • Beautifully Refurbished to a Very High Standard Throughout • Very Flexible Accommodation • Parking and Glorious Gardens Guide price £650,000 SITUATION Dovecote House sits in the middle of the pretty hamlet of Membland, which itself sits on the outskirts of the highly sought after creekside villages of Noss Mayo and Newton Ferrers. Steeped in history, this property perfectly complements its stunning South Devon surroundings. It is easy to understand why this part of the South Hams is so desirable, gorgeous rural scenery, beautiful beaches with waterside walks and sleepy, pretty little villages. Despite this rural idyll, the village has good access to the local towns and cities such as Plymouth, Modbury, Kingsbridge, Totnes and, slightly further afield, Exeter. An immaculate beautifully refurbished Grade II Listed 4 bed DESCRIPTION Dovecote House is a truly unique 18th century property that offers c. 4400 sq ft property in a stunning South Hams location. of contemporary beautifully refurbished space which marries harmoniously the old with the new. This semi detached property currently has 2 large bedrooms and 2 beautiful bathrooms in the main house and a further 2 bedrooms and bathroom in an attached annexe. The 2 properties, however, could easily be incorporated into one, if required. There is currently a huge studio room which offers a vast array of possibilities. The ground floor of the main property is beautifully arranged and it would be easy to knock through into the existing garage which would create a wonderfully large ground floor living area. -

South Devon and Dorset Coastal Aaadvisoryadvisory Group (SDADCAG)

South Devon and Dorset Coastal AAAdvisoryAdvisory Group (SDADCAG) Shoreline Management Plan Review (SMP2) Durlston Head to Rame Head Shoreline Management Plan (Final) June 2011 Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Page deliberately left blank for doubledouble----sidedsided printing Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Approved by 1 0 Draft – for Public Consultation 14/04/2009 HJ 2 0 Draft – working version for CSG 11/12/2009 JR 3 0 Draft Final – re-issued to NQRG 17/08/2010 JR 4 0 Final 06/01/2011 JR Halcrow Group Limited Ash House, Falcon Road, Sowton, Exeter, Devon EX2 7LB Tel +44 (0)1392 444252 Fax +44 (0)1392 444301 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their client, South Devon and Dorset Coastal Advisory Group, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2011 Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Page deliberately left blank for doubledouble----sidedsided printing Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Table of CCContentsContents 111 INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................... -

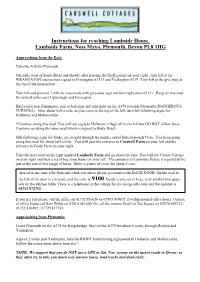

Instructions for Reaching Lambside Corner Cottage

Instructions for reaching Lambside House, Lambside Farm, Noss Mayo, Plymouth, Devon PL8 1HG Approaching from the East: Take the A38 for Plymouth. One mile west of South Brent and shortly after passing the Shell garage on your right , turn left at the WRANGATON intersection signed to Ermington A3121 and Yealmpton A379. Turn left at the give way at the top of the intersection. Turn left and proceed 1 mile to crossroads with give-way sign and turn right onto A3121. Keep on this road for several miles past Ugborough and Ermington. Half a mile past Ermington, stop at halt sign and turn right on the A379 towards Plymouth (DANGEROUS TURNING). After about half a mile, as you come to the top of the hill, turn left following signs for Holbeton and Mothecombe. *Continue along this road. You will see signs to Holbeton village off to the left but DO NOT follow these. Continue on along the same road which is signed to Stoke Beach. Still following signs for Stoke, go straight through the hamlet called Battisborough Cross. You keep going along this road for about half a mile. You will pass the entrance to Carswell Farm on your left and the entrance to Poole Farm on your right. Take the next road on the right marked Lambside Farm and go down the lane. You will see Corner Cottage on your right and then a set of big stone barns on your left. The entrance to Lambside House is a gravel drive just at the end of this range of barns. -

Hc010211pra Holbeton

EEC/11/28/HQ Public Rights of Way Committee 3 March 2011 Definitive Map Review 2010 – 2011 Parish of Holbeton Report of the Executive Director of Environment, Economy and Culture Please note that the following recommendation is subject to consideration and determination by the Committee before taking effect. Recommendation: It is recommended that a Modification Order be made to modify the Definitive Map and Statement by adding a restricted byway in respect of Suggestion 1 between points A and B as shown on drawing no. EEC/PROW/10/94. 1. Summary The report examines the Definitive Map Review in the Parish of Holbeton in the District of South Hams, including a Schedule 14 application made by the Trail Riders Fellowship for the addition of a byway open to all traffic from the county road near Pool Mill Farm to the county road near Henna Mill. 2. Background The original survey under s. 27 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 revealed five footpaths and three bridleways in Holbeton, which were recorded on the Definitive Map and Statement with a relevant date of 11 October 1954. The review of the Definitive Map, under s. 33 of the 1949 Act, which commenced in the 1970s but was never completed, produced one valid proposal for change to the Definitive Map at that time, namely the addition of a bridleway from Pool Mill to Henna Mill, which is discussed in this report. The Limited Special Review of RUPPs, carried out in the 1970s, did not affect the parish. The following Agreements and Orders have been made: Plympton St Mary Creation Agreement 1966 in respect of Footpath No. -

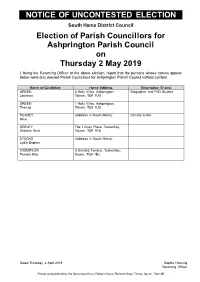

Notice of Uncontested Election Results 2019

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ashprington Parish Council on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ashprington Parish Council without contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) GREEN 8 Holly Villas, Ashprington, Biographer and PhD Student Laurence Totnes, TQ9 7UU GREEN 1 Holly Villas, Ashprington, Thomas Totnes, TQ9 7UU PEAREY (Address in South Hams) Climate Crisis Mike SEELEY Flat 1 Quay Place, Tuckenhay, Sheelah Ruth Totnes, TQ9 7EQ STOCKS (Address in South Hams) Lydia Daphne THOMPSON 9 Orchard Terrace, Tuckenhay, Pamela May Devon, TQ9 7EJ Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Sophie Hosking Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Follaton House, Plymouth Road, Totnes, Devon, TQ9 5NE NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aveton Gifford Parish Council on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aveton Gifford Parish Council without contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BROUSSON 5 Avon Valley Cottages, Aveton Ros Gifford, TQ7 4LE CHERRY 46 Icy Park, Aveton Gifford, Sue Kingsbridge, Devon, TQ7 4LQ DAVIS-BERRY Homefield, Aveton Gifford, TQ7 David Miles 4LF HARCUS Rock Hill House, Fore Street, Sarah Jane Aveton Gifford, -

Descendants of William Croker

Descendants of William Croker Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of William Croker 1-William Croker William married someone. He had one son: William. 2-William Croker William married someone. He had one son: John. 3-Sir John Croker John married Agnes Churchill, daughter of Giles Churchill. They had one son: John. 4-Sir John Croker John married "The Heiress" Of Corim. They had one son: John. 5-Sir John Croker John married "The Heiress" Of Dawnay. They had one son: John. 6-Sir John Croker, son of Sir John Croker and "The Heiress" Of Dawnay, died on 14 May 1508 in Lyneham, Devon. Noted events in his life were: • Miscellaneous: Cup & Standard Bearer to King Edward IV. John married Elizabeth Yeo, daughter of Robert Yeo and Alice Walrond. They had one son: John. 7-Sir John Croker was born in 1458 in Lyneham, Devon and died about 1547 in Lyneham, Devon about age 89. John married Elizabeth Pollard, daughter of Sir Lewis Pollard and Agnes Exte. Elizabeth was born in Girleston and died on 21 May 1531 in Lyneham, Devon. They had one son: John. 8-John Croker was born in 1515 and died on 30 Jun 1560 in Lyneham at age 45. John married Elizabeth Strode, daughter of Richard Strode and Agnes Milliton. They had two children: John and Thomas. 9-John Croker was born in 1532 in Lyneham and died on 18 Nov 1614 in Lyneham at age 82. John married Agnes Servington, daughter of John Servington Of Tavistock and Agnes Arscott. They had one son: Hugh.