Anthropocene Or Capitalocene?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Water Use Conflicts to Advance Collaborative Planning

water Article Understanding Water Use Conflicts to Advance Collaborative Planning: Lessons Learned from Lake Diefenbaker, Canada Jania S. Chilima 1,*, Jill Blakley 1,2, Harry P. Diaz 3 and Lalita Bharadwaj 1,4 1 School of Environment and Sustainability, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5C8, Canada; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (L.B.) 2 Department of Geography and Planning, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5C8, Canada 3 Department of Sociology and Social Studies, University of Regina, Regina, SK S4S 0A2, Canada; [email protected] 4 School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 2Z4, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-306-262-6920 Abstract: Conflicts around the multi-purpose water uses of Lake Diefenbaker (LD) in Saskatchewan, Canada need to be addressed to meet rapidly expanding water demands in the arid Canadian prairie region. This study explores these conflicts to advance collaborative planning as a means for improving the current water governance and management of this lake. Qualitative methodology that employed a wide participatory approach was used to collect focus group data from 92 individuals, who formed a community of water users. Results indicate that the community of water users is unified in wanting to maintain water quality and quantity, preserving the lake’s aesthetics, and reducing water source vulnerability. Results also show these users are faced with water resource conflicts resulting from lack of coherence of regulatory instruments in the current governance regime, Citation: Chilima, J.S.; Blakley, J.; and acceptable management procedures of both consumptive and contemporary water uses that Diaz, H.P.; Bharadwaj, L. -

Saskatchewan Water Governance Assessment Final Report

Saskatchewan Water Governance Assessment Final Report Unit 1E Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change Project H. Diaz, M. Hurlbert, J. Warren and D. R. Corkal October 2009 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations ………………………………………………………. 3 I Introduction ………………………………………………………… 5 II Methodology .……………………………………………………….. 5 III Integrative Discussion ……………………………………………… 9 IV Conclusions .………………………………………………………… 54 V References ………………………………………………………….. 60 VI Appendices …………………………………………………………. Appendix 1 - Organizational Overviews ..………………………… 62 Introduction ……………………………………………………… 62 Saskatchewan Watershed Authority ...……..………………….… 63 Saskatchewan Ministry for Environment …..………………….… 76 Saskatchewan Ministry for Agriculture .………………………… 85 SaskWater …………………………………….…………………. 94 Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration……………………… 103 Appendix 2 - Interview Summaries ……………………….……… 115 Saskatchewan Watershed Authority ……………………….……. 116 Saskatchewan Ministry for Environment ….…………………….. 154 Saskatchewan Ministry for Agriculture .…………………….…… 182 SaskWater ………………………………………………….……. 194 Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration …………………….. 210 Irrigation Proponents ……………………………………………. 239 Watershed Advisory Groups ……………………………………. 258 Environment Canada …………………………………………….. 291 SRC ..…………………………………………………………… 298 PPWB …………………………………………………………… 305 Focus Group …………………………………………………….. 308 Appendix 3 - Field Work Guide …………………………………. 318 2 Abbreviations AAFC – Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada ADD Boards – Agriculture Development and Diversification Boards AEGP - Agri-Environmental -

1 Lake Diefenbaker Reservoir Operating Plan Consultation

Lake Diefenbaker Reservoir Operating Plan Consultation Downstream Municipalities Meeting July 16, 2012, Park Town Hotel, Saskatoon Recorders: Robin Tod, Heather Davies Facilitator: Dazawray Landrie-Parker Stakeholders: Name Stakeholder Municipality Ben Boots Buffalo Pound Water Treatment Plant Paul Van Pul Hydraulic Archaeology James Harvey Pike Lake Rick Petrie RM of Canaan #225 Mel Henry RM of Corman Park Randy Ridgewell RM of Fertile Valley Eugene Matwishyn RM of Prince Albert Harvey Pippin RM of Vanscoy Brenda Wallace Saskatoon Galen Heinrichs Saskatoon Twyla Yoss Saskatoon Spencer Early Valley People Association Warren Rutherford Warman Russ McPherson Waterwolf Planning Commission William Lemisko Worldaway Farm Meeting Notes 10:00 am - Dazawray opened the meeting and asked the participants to introduce themselves. Dazawray went through an outline of the agenda. She ensured the stakeholders knew that the primary objective of the response session was to provide stakeholders the opportunity to share and discuss issues they perceive as relevant to the renewal of the Lake Diefenbaker Reservoir Operating Plan. Dazawray also reminded stakeholders to finish and send in their completed questionnaire to Robin Tod. The first part of the meeting was to discuss some of the challenges the downstream municipal stakeholders had related to the operation of Gardiner Dam. Challenges There was some concern that an audio recording of John Pomeroy’s presentation was not posted on the website. 1 Dam Safety o Concern was raised as to whether the Authority is collecting adequate data to ensure that Gardiner dam is safe. There was scepticism by participants that the Authority was providing accurate information when it came to the safety of Gardiner and other dams in the province. -

Polders of the World Final Report

POLDERS OFTH E WORLD FINAL REPORT INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM LELYSTAD THE NETHERLANDS 1983 THE SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZATION - Department of Civil Engineering- Delf t"Universit yo fTechnolog y - IJsselmeerpoldersDevelopmen t Authority -Ministr y ofTranspor t and PublicWork s - Committee forHydrologica l ResearchTN O -Associatio n forWate rManagemen t andLan d UsePlannin g CO-SPONSORS OFTH E SYMPOSIUM INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS - ^ood andAgricultur e Organization of theUnite d Nations (FAO) -Unite d NationsEducationa l Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) - Commission Internationale duGéni eRura l (CIGR) - International Association forHydrauli c Research (IAHR) - InternationalAssociatio n ofHydrologica l Sciences (IAHS) - International Association ofHydrogeologist s (IAH) - International Commission on Irrigation andDrainag e (ICID) - International Society of Soil Science (ISSS) - International Water ResourcesAssociatio n (IWRA) ORGANIZATIONS INTH ENETHERLAND S -Agricultura l University Wageningen - DelftHydraulic s Laboratory - International Institute forLan d Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI) - International Institute forHydrauli c andEnvironmenta l Engineering (IHE) - Joint CivilEngineerin g Organizations -Ministr y ofAgricultur e andFisheries : ForeignMarketin g andEconomi c CoooerationServic e Government Service forLan d andWate rUs e -Ministr y ofEconomi cAffairs : TheNetherland sForeig n TradeAgenc y -Ministr y ofEducatio n andScience : Directorate-General forScienc ePolic y -Ministr y ofTranspor t and PublicWork s Exposition CentreNe wLan d Information Division Rijkswaterstaat,Directorat e ofWate rManagemen tan d Hydraulic Research Rijkswaterstaat,Zuyde r ZeeProjec t Authority " Netherlands Engineering Consultants (NEDECO) - Research Institute forNatur eManagemen t (RIN) - Royal Institute ofEngineer s inTh eNetherland s (KIVI) - RoyalNetherland s Society forAgricultura l Science - Union ofWate r Boards EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 'POLDERSO FTH EWORLD ' Prof. Ir.W .A . Segeren,chairma n Ir.E .Schultz ,secretar y Mrs.W.J.M . -

Imagining the Dutch Polder Landscape: a Design by OMA from 1986

Journal of Landscape Architecture ISSN: 1862-6033 (Print) 2164-604X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjla20 Imagining the Dutch polder landscape: a design by OMA from 1986 Christophe Van Gerrewey To cite this article: Christophe Van Gerrewey (2015) Imagining the Dutch polder landscape: a design by OMA from 1986, Journal of Landscape Architecture, 10:3, 20-27, DOI: 10.1080/18626033.2015.1094900 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2015.1094900 Published online: 23 Sep 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjla20 Download by: [EPFL Bibliothèque] Date: 07 October 2015, At: 00:38 Imagining the Dutch polder landscape: a design by OMA from 1986 Christophe Van Gerrewey École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland Abstract Introduction: OMA and the Haarlemmermeerpolder In 1986, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) / Rem Koolhaas In 1986, Rem Koolhaas and OMA made a design for the Haarlemmer- created a landscape design for the Haarlemmermeerpolder, located between meerpolder, a large site in the heart of the Netherlands, with a complex Amsterdam, Leiden, and Haarlem. They were invited by urbanists and and emblematic history. This polder, almost 200 square kilometres in size, planners wanting to denounce the urban policy in the 1980s. Dutch spatial was, until the nineteenth century, the largest Dutch lake, nicknamed the Downloaded by [EPFL Bibliothèque] at 00:38 07 October 2015 development, once characterized by reclamation and bold city planning, ‘Waterwolf’due to its wild character. -

Water Management, Governance, and Heritage in Venice and Amsterdam

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2017 Cultural Heritage and Rising Seas: Water Management, Governance, and Heritage in Venice and Amsterdam Katherine D. Mitchell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Mitchell, Katherine D., "Cultural Heritage and Rising Seas: Water Management, Governance, and Heritage in Venice and Amsterdam" (2017). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 161. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/161 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Cultural Heritage and Rising Seas Water Management, Governance, and Heritage in Venice and Amsterdam Katherine Mitchell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Environmental Program College of Arts and Sciences Honors College University of Vermont May 2017 Advisors Kelley DiDio, PhD, University of Vermont Brendan Fisher, PhD, University of Vermont 2 Abstract Global climate change poses threats, including sea level rise, that will affect cultural heritage. Cultural heritage is “the legacy of physical artifacts and intangible heritage attributes of a group or society that are inherited from past generations, maintained in the present, and bestowed for the benefit of future generations” (UNESCO Office in Cairo, 2016).Venice and Amsterdam are two cities with cultural heritage sites and vulnerability to flooding as a result of geography and rising sea levels. -

River Basins Organizations

1 River Basin Organizations Author: Jerome Delli Priscoli1 1. North America2 1.1. The United States The United States operates under two major systems of water rights: riparian doctrine in the East and prior appropriation in the West. The quantifying of Native American tribal rights and their integration into these systems is becoming more important. The acequia system found in the Southwest is one of a few hybrids. It was inherited from the Spanish, who brought it from the Arab world. The United States of America is a federal system. The states are sovereign entities and they have control over water resources. Like other large countries in the world, river basin operations and organizations revolve first around the alignment of powers among these sovereign entities, which rarely fit river boundaries. Second, they revolve around the exercise of bureaucratic power within the federal and state governments. Multiple agencies work with water usually within their own mandates and sector. However, there are major federal interests affecting water distribution and use. In fact, one of the U.S.’s earliest court decisions was confining the power of the federal government to regulate commerce involving water navigation. Beyond interstate commerce, federal control over water has been established in a variety of areas, such as for emergencies, flood control, irrigation, public health, environmental issues, and fish and wildlife. Many of these interests have been institutionalized in numerous federal agencies, which present a formidable coordination task. Complex formulas for the mix of federal and state money in water resources development have evolved for different project purposes and water uses, such as flood control, navigation, recreation, water supply for irrigation, and hydroelectric power. -

How Narrative Water Ethics Contributes to Re-Theorizing Water Politics

water Article I Want to Tell You a Story: How Narrative Water Ethics Contributes to Re-theorizing Water Politics Simon P. Meisch 1,2 1 Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS), Berliner Str. 30, 14467 Potsdam, Germany; [email protected]; Tel.: +49-331-28822-491 2 International Centre for Ethics in the Sciences and Humanities (IZEW), University of Tuebingen, Wilhelmstr. 19, 72074 Tuebingen, Germany Received: 2 January 2019; Accepted: 25 March 2019; Published: 27 March 2019 Abstract: This paper explores potential contributions of narrative ethics to the re-theorization of the political in water governance, particularly seeking to rectify concerns regarding when water is excluded from cultural contexts and issues of power and dominance are ignored. Against this background, this paper argues for a re-theorization of the political in water governance, understood as the way in which diverse ideas about possible and desirable human-water relationships and just configurations for their institutionalization are negotiated in society. Theorization is conceived as the concretization of reality rather than its abstraction. Narrative ethics deals with the narrative structure of moral action and the significance of narrations for moral action. It occupies a middle ground and mediates between descriptive ethics that describe moral practices, and prescriptive ethics that substantiate binding norms. A distinguishing feature is its focus on people’s experiences and their praxis. Narrative water ethics is thus able to recognize the multitude of real and possible human-water relationships, to grasp people’s entanglement in their water stories, to examine moral issues in their cultural contexts, and, finally, to develop locally adapted notions of good water governance. -

Table of Contents

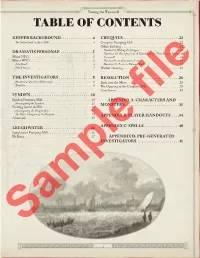

Taming the Waterwolf TABLE OF CONTENTS KEEPER BACKGROUND � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �4 CRUQUIUS � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �22 The Netherlands in April 1849 . 4 Cruquius Pumping Mill . .22 Office Building . .22 Handout 8: Waking the Dragon . 24 DRAMATIS PERSONAE � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �5 Handout 10: Excerpts from A Hand-book for Travellers in Devon & Major NPCs . .5 Cornwall . 24 Minor NPCs ���������������������������������������������������������������������������6 Handout 9: an Anonymous Letter . 24 John Knill . 6 Handout 11: Letter to Edward Knill . 24 Dutch Names . 7 Worker Housing . .25 THE INVESTIGATORS � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 RESOLUTION � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �26 Handout 2: The Cruel Waterwolf . 8 Back into the Mists ���������������������������������������������������������������26 Timeline . 8 The Opening of the Cruquius Mill . .28 Conclusion . .30 LYNDEN � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �10 Lynden Pumping Mill �����������������������������������������������������������10 APPENDIX A: CHARACTERS AND Investigating the Symbols . 12 MONSTERS � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �31 Finding Gerrit de Wit �����������������������������������������������������������13 Investigating the Dragón Rojo . 14 The Water Dungeon of the Rasphuis . 15 APPENDIX B: PLAYER HANDOUTS � � � �34 Aftermath . .15 LEEGHWATER � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �16 APPENDIX C: SPELLS � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Decision Making on Flood Management in the Meuse River

Technology in Society XX (2006) xxx-xxx Flood safety in the Netherlands: Authors'copy the Dutch response to Hurricane Katrina Anna J. Wesselink* Dept. of Water Engineering and Management, University of Twente, PO Box 217, 7500 AE Enschede, The Netherlands _______________________________________________________________________ Abstract In this paper I discuss why the Dutch culture, although highly technological, remains vulnerable to flooding, with no apparent choice except to continue with its historically developed system for flood risk management. I show that this vulnerability is socially constructed. It has arisen as a result of a long history of technological choices, the current political decisions related to financing and a general lack of risk awareness. The question whether there is a need or even a possibility to escape from the present technological lock-in seems to remain out of bounds for a society that imagines flood protection to be absolute. The need for similar absolute protection was demanded in New Orleans shortly after Hurricane Katrina caused extensive flooding there. Because of its circumstances and its much shorter history, New Orleans appears to have an opportunity to deal with flood risk in more creative ways. Key words: Technological lock-in; Vulnerability; Flood management; Risk management __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. The Netherlands: flood defense as technological lock-in Ever since ancient Dutch society decided to start draining the coastal wetlands of what is now the Netherlands, it has gradually maneuvered itself into what is now a technological lock-in. This decision to drain began about the year 1000, but evidence of even earlier local efforts also has been found [1,2]. -

Martijn F Van Staveren

BRINGING IN THE FLOODS BRINGING IN THE FLOODS A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON CONTROLLED FLOODING IN THE DUTCH, BANGLADESH AND VIETNAMESE DELTAS Martijn F van Staveren Martijn F van Martijn F van Staveren Propositions 1. Understanding flooding as being harmful obscures thinking about the potential benefits it can bring. (this thesis) 2. Flood management challenges lie in the future, solutions can be found in the past. (this thesis) 3. The need in science to publish unique material invokes academic protectionism. 4. The use of infographics to improve the dissemination and uptake of research findings is compromised by word count 'penalties' and color printing charges as is common practice among scientific journals. 5. Completing a PhD with delay is a proxy of perseverance. 6. Comparing the Netherlands, Bangladesh and Vietnam is like comparing soccer, cricket and table tennis: all ball sports but the number of players, the size of the field, and the rules of the game are different. Propositions belonging to the thesis, entitled ‘Bringing in the floods. A comparative study on controlled flooding in the Dutch, Bangladesh and Vietnamese deltas.’ Martijn Floris van Staveren Wageningen, 8 November 2017 Bringing in the floods A comparative study on controlled flooding in the Dutch, Bangladesh and Vietnamese deltas Martijn F. van Staveren Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr J.P.M. van Tatenhove Personal chair at the Environmental Policy Group Wageningen University & Research Co-promotors Dr J.F. Warner Associate professor, Sociology of Development and Change Group Wageningen University & Research Dr P. Wester Chief Scientist Water Resources Management International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) Affiliated researcher Water Resources Management Group Wageningen University & Research Other members Prof. -

Anthropocene Or Capitalocene?

Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism Edited by Jason W. Moore Contents acknowledgments xi introduction Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism 1 Jason W. Moore PART I THE ANTHROPOCENE AND ITS DISCONTENTS: TOWARD CHTHULUCENE? one On the Poverty of Our Nomenclature 14 Eileen Crist two Staying with the Trouble: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene 34 Donna J. Haraway PART II HISTORIES OF THE CAPITALOCENE three The Rise of Cheap Nature 78 Jason W. Moore four Accumulating Extinction: Planetary Catastrophism in the Necrocene 116 Justin McBrien five The Capitalocene, or, Geoengineering against Capitalism’s Planetary Boundaries 138 Elmar Altvater PART III CULTURES, STATES, AND ENVIRONMENT-MAKING six Anthropocene, Capitalocene, and the Problem of Culture 154 Daniel Hartley seven Environment-Making in the Capitalocene: Political Ecology of the State 166 Christian Parenti references 185 contributors 210 index 213 Acknowledgments It was a spring day in southern Sweden in 2009. I was talking with Andreas Malm, then a PhD student at Lund University. “Forget the Anthropocene,” he said. “We should call it the Capitalocene!” At the time, I didn’t pay much attention to it. “Yes, of course,” I thought. But I didn’t have a sense of what the Capitalocene might mean, beyond a reasonable—but not particularly interesting—claim that capitalism is the pivot of today’s biospheric crisis. This was also a time when I began to rethink much of environmental studies’ conventional wisdom. This conventional wisdom had become atmospheric. It said, in effect, that the job of environmental studies schol- ars is to study “the” environment, and therefore to study the environmen- tal context, conditions, and consequences of social relations.