CASE STUDY: Jalaud, Barotac Nuevo, Iloilo Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1

COST OF DOING BUSINESS IN THE PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2017 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1 2 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 F O R E W O R D The COST OF DOING BUSINESS is Iloilo Provincial Government’s initiative that provides pertinent information to investors, researchers, and development planners on business opportunities and investment requirements of different trade and business sectors in the Province This material features rates of utilities, such as water, power and communication rates, minimum wage rates, government regulations and licenses, taxes on businesses, transportation and freight rates, directories of hotels or pension houses, and financial institutions. With this publication, we hope that investors and development planners as well as other interested individuals and groups will be able to come up with appropriate investment approaches and development strategies for their respective undertakings and as a whole for a sustainable economic growth of the Province of Iloilo. Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 3 4 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword I. Business and Investment Opportunities 7 II. Requirements in Starting a Business 19 III. Business Taxes and Licenses 25 IV. Minimum Daily Wage Rates 45 V. Real Property 47 VI. Utilities 57 A. Power Rates 58 B. Water Rates 58 C. Communication 59 1. Communication Facilities 59 2. Land Line Rates 59 3. Cellular Phone Rates 60 4. Advertising Rates 61 5. Postal Rates 66 6. Letter/Cargo Forwarders Freight Rates 68 VII. -

Iloilo Provincial Profile 2012

PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile TIUY Research and Statistics Section i Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile P R E F A C E The Annual Iloilo Provincial Profile is one of the endeavors of the Provincial Planning and Development Office. This publication provides a description of the geography, the population, and economy of the province and is designed to principally provide basic reference material as a backdrop for assessing future developments and is specifically intended to guide and provide data/information to development planners, policy makers, researchers, private individuals as well as potential investors. This publication is a compendium of secondary socio-economic indicators yearly collected and gathered from various National Government Agencies, Iloilo Provincial Government Offices and other private institutions. Emphasis is also given on providing data from a standard set of indicators which has been publish on past profiles. This is to ensure compatibility in the comparison and analysis of information found therewith. The data references contained herewith are in the form of tables, charts, graphs and maps based on the latest data gathered from different agencies. For more information, please contact the Research and Statistics Section, Provincial Planning & Development Office of the Province of Iloilo at 3rd Floor, Iloilo Provincial Capitol, and Iloilo City with telephone nos. (033) 335-1884 to 85, (033) 509-5091, (Fax) 335-8008 or e-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also visit our website at www.iloilo.gov.ph. Research and Statistics Section ii Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Message of the Governor am proud to say that reform and change has become a reality in the Iloilo Provincial Government. -

Notice to the DEPOSITORS of the Closed Bangko Buena Consolidated Inc. (A Rural Bank)

PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION Notice to the DEPOSITORS of the Closed Bangko Buena Consolidated Inc. (A Rural Bank) Bangko Buena Consolidated, Inc. (A Rural Bank) [Bank] with Head Office address at #23 Valeria St. cor. Rizal St., Brgy. Nonoy, City of Iloilo has been prohibited from doing business in the Philippines by the Monetary Board of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in accordance with Section 30 of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 7653 (New Central Bank Act) (Resolution No. 1194.A dated July 26, 2018). R.A. No. 3591, as amended (PDIC Charter), mandates the PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION (PDIC), as Deposit Insurer, to pay all valid deposit accounts and insurance claims up to the maximum deposit insurance coverage of PhP500,000.00. The PDIC will conduct an onsite servicing of deposit insurance claims of depositors of the Bank from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM. PAYOUT SITES FOR DEPOSIT INSURANCE CLAIMS: Banking Office / Branch Date Address Head Office BankingAugust Office 29 & 30, 2018 #23 Valeria St. cor. Rizal St. Brgy.Payout Nonoy, City ofSite Iloilo Bacolod August 29, 2018 San Juan – Burgos29-A CarandangSt., Brgy. 10, St.,Bacolod Barangay City C (Poblacion), Head Office Rosario, Batangas Barotac Nuevo August 29 & 30, 2018 M. H. del Pilar St., Brgy. Ilaud Poblacion, Barotac Nuevo, Iloilo Buenavista Santa TeresitaAugust 29, Branch 30 & 31, 2018 Agri-Eco Hall,Brgy. Guimaras Bihis, State Santa College Teresita, Batangas Culasi August 29, 30 & 31, 2018 Brgy. Centro Sur (Pob.), Culasi, Antique Dao August 29, 30 & 31, 2018 Brgy. Poblacion Ilaya, Dao, Capiz Lambunao August 29, 30 & 31, 2018 Coalition St. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

I PfV- A:Cr~qq0 :D;J b3 9 I I I FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCEPTANCE AND CONTINUATION I OFIUD A COMPARATIVE STUDY I PHILIPPINES I FmalReport I I ASIA & NEAR EAST OPERATIONS RESEARCH AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT I FAMILY PLANNING OPERATIONS RESEARCH I AND TRAINING (FPORT) PROGRAM PopulatIOn CouncIl, ManIla I m collaboratIOn with the Department of Health I USAID Contract No DPE-C-OO-90-0002-10 I StrategIes for Improvmg FamIly Plannmg ServIce DelIvery I July 1998 I I I I I I ACKNOWLEDGMENT I Tills project was conducted by Populatlon CouncIl-Mamla, m collaboratIOn wIth the Department of Health under the ANE ORiTA Project wIth support from the Office of I PopulatIOn Health and NutntIOn (OPHN), US Agency for International Development, Contract No DPE-3030-C-OO-90-0002-1 0 I PopulatIOn CouncIl, ManIla would hke to acknowledge the mdIvIduals and I mstltutIOns who helped m carrymg out thIS project • Dr Magdalena C Cab arab an, the head of the research team and the overall I coordmator ofthe study m ItS two study SItes, Mlsamls On ental and IloIlo • Dr Jayantl Tuladhar, PopulatIOn CouncIl, New Delln for ills techmcal aSSIstance m I the questIOnnaire deSIgn and data analYSIS for the modified SA used m tills study • Dr Josefina Cablgon for her asSIstance m data analYSIS and Mr FIono Argmllas ills I work m the data management and programmmg • The Research InstItute ofMmdanao Culture, as represented by Mrs Manlou Tabor, Operatlons Manager, who handled the admmlstratlve aspects of the project and the I recruItment of project staff • The SOCIal SCIence -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register Summary 85 84 4 04-2015 301 B1 023545 1 -4 0 0 5 3818 29 22 4 05-2015 301 B1

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MAY 2015 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3818 023545 BACOLOD CITY HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 84 5 0 0 -4 1 85 3818 023547 BACOLOD CITY SUGARLANDIA PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 22 4 0 3 0 7 29 3818 023586 ILOILO HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 88 0 0 0 -16 -16 72 3818 023600 MOUNT KANLAON PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 85 15 0 3 -11 7 92 3818 023603 OCCIDENTAL NEGROS HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 68 2 0 0 -18 -16 52 3818 029600 BACOLOD CITY CAPITOL PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 26 2 0 0 -1 1 27 3818 030211 BACOLOD CITY BACOLOD AIRPORT PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 21 10 0 1 -9 2 23 3818 031135 BACOLOD CITY MT KANLANDOG PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 56 5 0 0 -2 3 59 3818 031712 ILOILO CITY EXECUTIVE PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 32 0 0 0 -3 -3 29 3818 031713 POTOTAN PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 60 6 0 0 -6 0 60 3818 031888 CAPIZ L C PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 28 17 0 0 0 17 45 3818 033755 ILOILO FORT SAN PEDRO PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 18 0 0 0 0 0 18 3818 034135 BACOLOD KATIPUNAN PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 11 0 0 0 0 0 11 3818 037381 ILOILO CITY INTEGRATED PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 43 8 0 0 -1 7 50 3818 041571 ILOILO CITY METRO PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 46 10 2 0 -2 10 56 3818 045379 BACOLOD TRADERS PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 28 5 0 0 0 5 33 3818 047751 ILOILO CITY PROFESSIONAL PHILIPPINES 301 B1 -

Infrastructure

Infrastructure Php 3,968.532 M Roads & Bridges Php 2,360.126 M Sch bldgs/classrooms Php 958.116 M Electrical Facilities 297.400 M Health Facilities and Others Php 352.891M Cost of Assistance Provided by Government Agencies/LGUs/NGOs (TAB E) NDCC - Php 16,233,375 DSWD - Php 26,018,019 DOH - Php 15,611,099 LGUs - Php 19,874,903 NGOs - Php 2,595,130 TOTAL - Php 80,332,527 International and Local Assistance/Donations (Tab F) Total International/Donations Cash - US $ 510,000 Aus $ 500,000. In kind - Php 8,000,000 (generator sets, and other non-food items NFI’s) US $ 650,000 (relief flight) Local Assistance/Donations Cash - Php 1,025,000 In Kind - Php 95,539 (assorted relief commodities) 90 sets disaster kits Areas Declared under a State of Calamity by their respective Sanggunians : 10 Provinces Albay, Antique, Iloilo, Aklan, Capiz, Sarangani, Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, Marinduque and Romblon 8 Municipalities Paombong and Obando in Bulacan; Carigara, Leyte; and Lake Sebu, Surallah, Sto. Nino and Tiboli in South Cotabato, and San Fernando, Romblon 3 Cities Cotabato City, Iloilo City and Passi City 9 Barangays (Zamboanga City) – Vitali, Mangusu, San Jose Gusu, Tugbungan, Putik, Baliwasan, Tumaga, Sinunuc and Sta. Catalina 2 II. Actions Taken and Resources Mobilized by Agencies: Relief and Recovery Operations NDCC-OPCEN Facilitated release of 17,790 sacks of rice in 11 regions (I – 200, III – 950, IV-A – 1,300, IV-B – 1,150, V – 250, VI – 11,300, VII – 500, VIII – 500, XII – 740, NCR – 300, ARMM – 600) amounting to P16,233,375.00 AFP-PAF Disaster Response Transported the 15 th sortie (assorted goods and medicine boxes) from DZRH & PAGCOR to Iloilo III. -

The Role of Local Institutions in Reducing Vulnerability to Recurrent Natural Disasters and in Sustainable Livelihoods Development Philippines

INSTITUTIONS FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT 8 CASE STUDY The role of local institutions in reducing vulnerability to recurrent natural disasters and in sustainable livelihoods development Philippines Prepared by the Asian Disaster preparedness Center Under the overall technical guidance and supervision from Stephan Baas Rural Institutions and Participation Service FAO Rural Development Division ASIAN DISASTER PREPAREDNESS CENTER FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2006 The Institutions for Rural Development Series includes four categories of documents (Conceptual Notes, Guidelines, Case Studies, Working Papers) aiming at supporting efforts by countries and their development partners to improve institutions, be they public, private, centralized or decentralized. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ISBN 978-92-5-105636-3 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: Chief Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch Information Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to: [email protected] © FAO 2006 The Role of Local Institutions in Reducing Vulnerability to Natural Hazard PREFACE The Global data show that natural hazards are increasing in frequency and intensity. -

Last Name) (First Name)

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT Regional Office No. VI Special Program for Employment of Students (SPES) List of SPES Beneficiaries CY 2018 As of DECEMBER 31, 2019 ACCOMPLISH IN CAPITAL LETTERS Name of Student No. Province Employer Address (Last Name) (First Name) 1 AKLAN LGU BALETE ARANAS CYREL KATE ARANAS, BALETE, AKLAN 2 AKLAN LGU BALETE DE JUAN MA. JOSELLE MAY MORALES, BALETE, AKLAN 3 AKLAN LGU BALETE DELA CRUZ ELIZA CORTES, BALETE, AKLAN 4 AKLAN LGU BALETE GUIBAY RESIA LYCA CALIZO, BALETE, AKLAN 5 AKLAN LGU BALETE MARAVILLA CHRISHA SEPH ALLANA POBLACION, BALETE, AKLAN 6 AKLAN LGU BALETE NAGUITA QUENNIE ANN ARCANGEL, BALETE, AKLAN 7 AKLAN LGU BALETE NERVAL ADE FULGENCIO, BALETE, AKLAN 8 AKLAN LGU BALETE QUIRINO PAULO BIANCO ARANAS, BALETE, AKLAN 9 AKLAN LGU BALETE REVESENCIO CJ POBLACION, BALETE, AKLAN 10 AKLAN LGU BALETE SAUZA LAIZEL ANNE GUANKO, BALETE, AKLAN 11 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE AMBAY MA. JESSA CARMEN, PANDAN, ANTIQUE 12 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE ARCEÑO SHAMARIE LYLE ANDAGAO, KALIBO, AKLAN 13 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BAUTISTA CATHERINE MAY BACHAO SUR, KALIBO, AKLAN 14 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BELINARIO JESSY ANNE LOUISE TAGAS, TANGALAN, AKLAN 15 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BRACAMONTE REMY CAMALIGAN, BATAN, AKLAN 16 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE CONTRATA MA. CRISTINA ASLUM, IBAJAY, AKLAN 17 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE CORDOVA MARVIN ANDAGAO, KALIBO, AKLAN 18 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DE JUAN CELESTE TAGAS, TANGALAN, AKLAN 19 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DELA CRUZ RALPH VINCENT BUBOG, NUMANCIA, AKLAN 20 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DELIMA BLESSIE JOY POBLACION, LIBACAO, AKLAN 21 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DESALES MA. -

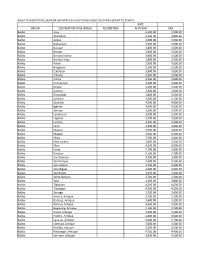

Point to Point Pick Up/Drop Off Rates Kalibo to Any

POINT TO POINT PICK UP/DROP OFF RATES KALIBO TO ANY POINT OF PANAY (POINT TO POINT) RATE ORIGIN DESTINATION (VISE VERSA) KILOMETERS AUV/VAN CAR Kalibo Ajuy 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Alimodian 4,100.00 3,800.00 Kalibo Anilao 4,000.00 3,700.00 Kalibo Badiangan 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Balasan 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Banate 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Barotac Nuevo 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Barotac Viejo 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Batad 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Bingawan 3,100.00 2,900.00 Kalibo Cabatuan 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Calinog 3,200.00 3,000.00 Kalibo Carles 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Concepcion 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Dingle 3,400.00 3,100.00 Kalibo Duenas 3,300.00 3,000.00 Kalibo Dumangas 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Estancia 4,000.00 3,700.00 Kalibo Guimbal 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Igbaras 4,600.00 4,300.00 Kalibo Janiuay 3,600.00 3,300.00 Kalibo Lambunao 3,500.00 3,200.00 Kalibo Leganes 3,700.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Lemery 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Leon 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Maasin 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Miagao 4,600.00 4,300.00 Kalibo Mina 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo New Lucena 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Oton 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Pavia 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Pototan 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo San Dionisio 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo San Enrique 3,400.00 3,100.00 Kalibo San Joaquin 4,700.00 4,400.00 Kalibo San Miguel 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo San Rafael 3,500.00 3,200.00 Kalibo Santa Barbara 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Sara 4,100.00 3,800.00 Kalibo Tigbauan 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Tubungan 4,500.00 4,200.00 Kalibo Zarraga 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo -

Iloilo Capiz Antique Aklan Negros Occidental

PHILIPPINES: Summary of Planned Cash Activities in REGION VI (Western Visayas) (as of 24 Feb 2014) Malay Planned Cash Activities 0 Buruanga Nabas 1 - 5 6 - 10 11 - 20 Libertad Ibajay Aklan > 20 Pandan Tangalan Numancia Makato Kalibo Lezo New Washington Malinao Banga Capiz Sebaste Roxas City Batan Panay Carles Balete Altavas Ivisan Sapi-An Madalag Pilar Balasan Estancia Panitan Mambusao Sigma Culasi Libacao Pontevedra President Roxas Batad Dao Jamindan Ma-Ayon San Dionisio Cuartero Tibiao Dumalag Sara Barbaza Tapaz Antique Dumarao Lemery Concepcion Bingawan Passi City Laua-An Calinog San Rafael Ajuy Lambunao San Enrique Bugasong Barotac Viejo Duenas Banate Negros Valderrama Dingle Occidental Janiuay Anilao Badiangan Mina Pototan Patnongon Maasin Iloilo Manapla Barotac Nuevo San Remigio Cadiz City Alimodian Cabatuan Sagay City New Lucena Victorias City Leon Enrique B. Magalona ¯ Belison Dumangas Zarraga Data Source: OCHA 3W database, Humanitarian Cluster lead organizations, GADMTubungan Santa Barbara Created 14 March 2014 San Jose Sibalom Silay City Escalante City 0 3 6 12 Km Planned Cash Activities in Region VI by Province, Municipality and Type of Activity as of 24 February 2014 Cash Grant/ Cash Grant/ Cash for Work Province Municipality Cash Voucher Transfer TOTAL (CFW) (conditional) (unconditional) BALETE 0 5 0 0 5 IBAJAY 0 0 0 1 1 AKLAN LIBACAO 0 1 0 0 1 MALINAO 0 8 0 1 9 BARBAZA 0 0 0 1 1 CULASI 0 0 0 1 1 LAUA-AN 0 0 0 1 1 ANTIQUE SEBASTE 0 0 0 1 1 TIBIAO 0 0 0 1 1 not specified 0 1 0 0 1 CUARTERO 0 0 0 1 1 DAO 0 6 0 0 6 JAMINDAN -

Iloilo Antique Negros Occidental Capiz Aklan Guimaras

Pilar Buruanga Makato Kalibo New Washington Sigma Humanity First PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC IOM Citizens' Disaster Response Center IOM Emergency Shelter PRCS - IFRC Humanity First PRCS - IFRC Banga Tangalan IOM Welt Hunger Hilfe Activities by Municipality Malay IOM PRCS - IFRC Balete PRAY ShelterBox PRCS -IFRC PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC World Vision (Roxas) Buruanga Nabas Numancia Welt Hunger Hilfe Ivisan Roxas City Ibajay PRCS - IFRC Carles 3W map summary Libertad Altavas IOM Citizens' Disaster Response Center DFID - HMS Illustrious IOM PRAY Humanity First DfID (British Navy) Pandan Tangalan PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC IOM MSF-CH Produced April 15, 2014 Numancia Batan PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC Lezo Makato Kalibo IOM Save the Children Panay Pontevedra This map depicts data PRCS - IFRC Lezo PRCS - IFRC Humanity First Humanity First Balasan gathered by the Shelter Approx. 75km Sebaste Malinao World Vision New Washington IOM IOM PRCS - IFRC Cluster about agencies Caluya Sapi-An PRAY PRAY who are responding to Sebaste Malinao Banga Save the Children DFID - HMS Illustrious IOM PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC Typhoon Yolanda. PRAY IOM PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC Roxas City ShelterBox ShelterBox Balete Estancia Batan Carles Any agency listed may Panay DFID - HMS Illustrious Ivisan have projects at different Madalag Altavas IOM Aklan Sapi-An stages of completion (e.g. Madalag Pilar MSF-CH Antique completed, ongoing or PRCS - IFRC Pontevedra Balasan Save the Children Jamindan Mambusao Panitan planned interventions). Sigma President Roxas Estancia Libacao World Vision Batad Culasi Culasi Jamindan Libacao Handicap International IOM IOM Capiz President Roxas Batad PRCS - IFRC IOM PRCS - IFRC Dao MSF-CH Who What Where (3W) information on shelter activities ShelterBox ShelterBox Ma-Ayon Save the Children represents agency information reported to the Shelter Cluster by Green Forum Western Visayas UNHCR San Dionisio April 13, 2014. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register Summary 53 66 4 06-2016 301 B1 023545 -13 -13 0 0 0 3818 29 29 4 06-2016

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JUNE 2016 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3818 023545 BACOLOD CITY HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 66 0 0 0 -13 -13 53 3818 023547 BACOLOD CITY SUGARLANDIA PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 29 1 0 0 -1 0 29 3818 023586 ILOILO HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2016 62 6 1 0 0 7 69 3818 023600 MOUNT KANLAON PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 83 8 1 0 -19 -10 73 3818 023603 OCCIDENTAL NEGROS HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2016 50 4 0 0 -2 2 52 3818 029600 BACOLOD CITY CAPITOL PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2016 27 0 0 0 0 0 27 3818 030211 BACOLOD CITY BACOLOD AIRPORT PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2016 18 1 0 0 -4 -3 15 3818 031135 BACOLOD CITY MT KANLANDOG PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 40 7 3 0 -3 7 47 3818 031712 ILOILO CITY EXECUTIVE PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2016 26 0 0 0 0 0 26 3818 031713 POTOTAN PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 48 6 0 0 -14 -8 40 3818 031888 CAPIZ L C PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 45 1 0 0 -21 -20 25 3818 033755 ILOILO FORT SAN PEDRO PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2016 18 1 0 0 0 1 19 3818 034135 BACOLOD KATIPUNAN PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 11 0 0 0 0 0 11 3818 037381 ILOILO CITY INTEGRATED PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 46 10 0 0 -4 6 52 3818 041571 ILOILO CITY METRO PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 57 2 0 0 -10 -8 49 3818 045379 BACOLOD TRADERS PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 06-2016 29 0 0 0 -5 -5 24 3818 047751 ILOILO CITY PROFESSIONAL PHILIPPINES 301