Local Governments and Community-Based Response to Changes in Socio-Economic Structures Due to Flood Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1

COST OF DOING BUSINESS IN THE PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2017 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1 2 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 F O R E W O R D The COST OF DOING BUSINESS is Iloilo Provincial Government’s initiative that provides pertinent information to investors, researchers, and development planners on business opportunities and investment requirements of different trade and business sectors in the Province This material features rates of utilities, such as water, power and communication rates, minimum wage rates, government regulations and licenses, taxes on businesses, transportation and freight rates, directories of hotels or pension houses, and financial institutions. With this publication, we hope that investors and development planners as well as other interested individuals and groups will be able to come up with appropriate investment approaches and development strategies for their respective undertakings and as a whole for a sustainable economic growth of the Province of Iloilo. Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 3 4 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword I. Business and Investment Opportunities 7 II. Requirements in Starting a Business 19 III. Business Taxes and Licenses 25 IV. Minimum Daily Wage Rates 45 V. Real Property 47 VI. Utilities 57 A. Power Rates 58 B. Water Rates 58 C. Communication 59 1. Communication Facilities 59 2. Land Line Rates 59 3. Cellular Phone Rates 60 4. Advertising Rates 61 5. Postal Rates 66 6. Letter/Cargo Forwarders Freight Rates 68 VII. -

Philippines: Typhoon Fengshen

Emergency appeal n° MDRPH004 Philippines: GLIDE n° TC-2008-000093-PHL Operations update n° 4 31 December 2008 Typhoon Fengshen Period covered by this Ops Update: 24 September to 15 December 2008 Appeal target (current): CHF 8,310,213 (USD 8 million or EUR 5.1 million); with this Operations Update, the appeal has been revised to CHF 1,996,287 (USD 1,878,149 or EUR 1,343,281) <click here to view the attached Revised Emergency Appeal Budget> Appeal coverage: To date, the appeal is 87%. Funds are urgently needed to enable the Philippine National Red Cross to provide assistance to those affected by the typhoon.; <click here to go directly to the updated donor response A transitional shelter house in the midst of being built in the municipality of report, or here to link to contact Santa Barbara, Ilo Ilo province. Photo: Philippine National Red Cross. details > Appeal history: • A preliminary emergency appeal was launched on 24 June 2008 for CHF 8,310,213 (USD 8 million or EUR 5.1 million) for 12 months to assist 6,000 families. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 200,000 was allocated from the International Federation’s DREF. Summary: The onslaught of typhoon Fengshen which hit the Philippines on 18 June 2008, followed by floods and landslides, have left in its wake urgent needs among poverty-stricken communities. According to the National Disaster Coordinating Council (NDCC), approximately four million people have been affected through out the country by typhoon Fengshen. More than 81,000 houses were totally destroyed and a further 326,321 seriously damaged. -

Iloilo Provincial Profile 2012

PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile TIUY Research and Statistics Section i Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile P R E F A C E The Annual Iloilo Provincial Profile is one of the endeavors of the Provincial Planning and Development Office. This publication provides a description of the geography, the population, and economy of the province and is designed to principally provide basic reference material as a backdrop for assessing future developments and is specifically intended to guide and provide data/information to development planners, policy makers, researchers, private individuals as well as potential investors. This publication is a compendium of secondary socio-economic indicators yearly collected and gathered from various National Government Agencies, Iloilo Provincial Government Offices and other private institutions. Emphasis is also given on providing data from a standard set of indicators which has been publish on past profiles. This is to ensure compatibility in the comparison and analysis of information found therewith. The data references contained herewith are in the form of tables, charts, graphs and maps based on the latest data gathered from different agencies. For more information, please contact the Research and Statistics Section, Provincial Planning & Development Office of the Province of Iloilo at 3rd Floor, Iloilo Provincial Capitol, and Iloilo City with telephone nos. (033) 335-1884 to 85, (033) 509-5091, (Fax) 335-8008 or e-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also visit our website at www.iloilo.gov.ph. Research and Statistics Section ii Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Message of the Governor am proud to say that reform and change has become a reality in the Iloilo Provincial Government. -

Disaster Preparedness Level, Graph Showed the Data in %, Developed on the Basis of Survey Conducted in Region Vi

2014 Figures Nature Begins Where Human Predication Ends Typhoon Frank (Fengshen) 17th to 27th June, 2008 Credit: National Institute of Geological Sciences, University of the Philippines, 2012 Tashfeen Siddique – Research Fellow AIM – Stephen Zuellig Graduate School of Development Management 8/15/2014 Nature Begins Where Human Predication Ends Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations: ...................................................................................................... iv Brief History ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Philippines Climate ........................................................................................................................... 2 Chronology of Typhoon Frank ....................................................................................................... 3 Forecasting went wrong .................................................................................................................. 7 Warning and Precautionary Measures ...................................................................................... 12 Typhoon Climatology-Science ..................................................................................................... 14 How Typhoon Formed? .............................................................................................................. 14 Typhoon Structure ..................................................................................................................... -

CASE STUDY: Jalaud, Barotac Nuevo, Iloilo Province

CASE STUDY: Jalaud, Barotac Nuevo, Iloilo Province Background Barotac Nuevo is a second-class municipality in the province of Iloilo, Philippines (Figure 1). The town is surrounded by the municipality of Pototan in the west, Dingle to the northwest, Anilao to the northeast, and Dumangas to the South. It has a population of 51,867 residents in 2010 census subdivided into 29 barangays, namely: Acuit, Agcuyawan Calsada, Agcuyawan Pulo, Bagongbong, Baras, Bungca, Cabilauan, Cruz, Guintas, Igbong, Ilaud Poblacion, Ilaya Poblacion, Jalaud, Lagubang, Lanas, Lico-an, Linao, Monpon, Palaciawan, Patag, Salihid, So-ol, Sohoton, Tabuc-Suba, Tabucan, Talisay, Tinorian, Tiwi, and Tubungan (Province of Iloilo, 2018). Figure 1. Location profile of Barotac Nuevo (Barotac Nuevo Iloilo, 2018) The Barotac Nuevo mangrove rehabilitation site was originally planted with species such as bakhaw, bungalon, pagatpat, and lapis-lapis. However, due to government lease agreements, the mangrove forest was destroyed and converted to fishponds. Table 1 shows the timeline of the status of mangroves in Barotac Nuevo from 1970s to present. According to a focus group discussion conducted among community members in Jalaud, Barotac Nueva, productive fishponds were present from 1970-1989. The community benefited from marine products such as fishes (e.g. milkfish), crab, shells, and shrimps (pasayan). Dikes were built during this time and fishpond lease agreements (FLAs) were established. However, the fishponds were abandoned in 1990 due to the destruction of the main dike brought about by strong waves. The local government unit (LGU) was later notified by the community on the presence of the abandoned and unutilized fishponds. This gave way to the reversion of the site back into mangroves. -

Notice to the DEPOSITORS of the Closed Bangko Buena Consolidated Inc. (A Rural Bank)

PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION Notice to the DEPOSITORS of the Closed Bangko Buena Consolidated Inc. (A Rural Bank) Bangko Buena Consolidated, Inc. (A Rural Bank) [Bank] with Head Office address at #23 Valeria St. cor. Rizal St., Brgy. Nonoy, City of Iloilo has been prohibited from doing business in the Philippines by the Monetary Board of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in accordance with Section 30 of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 7653 (New Central Bank Act) (Resolution No. 1194.A dated July 26, 2018). R.A. No. 3591, as amended (PDIC Charter), mandates the PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION (PDIC), as Deposit Insurer, to pay all valid deposit accounts and insurance claims up to the maximum deposit insurance coverage of PhP500,000.00. The PDIC will conduct an onsite servicing of deposit insurance claims of depositors of the Bank from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM. PAYOUT SITES FOR DEPOSIT INSURANCE CLAIMS: Banking Office / Branch Date Address Head Office BankingAugust Office 29 & 30, 2018 #23 Valeria St. cor. Rizal St. Brgy.Payout Nonoy, City ofSite Iloilo Bacolod August 29, 2018 San Juan – Burgos29-A CarandangSt., Brgy. 10, St.,Bacolod Barangay City C (Poblacion), Head Office Rosario, Batangas Barotac Nuevo August 29 & 30, 2018 M. H. del Pilar St., Brgy. Ilaud Poblacion, Barotac Nuevo, Iloilo Buenavista Santa TeresitaAugust 29, Branch 30 & 31, 2018 Agri-Eco Hall,Brgy. Guimaras Bihis, State Santa College Teresita, Batangas Culasi August 29, 30 & 31, 2018 Brgy. Centro Sur (Pob.), Culasi, Antique Dao August 29, 30 & 31, 2018 Brgy. Poblacion Ilaya, Dao, Capiz Lambunao August 29, 30 & 31, 2018 Coalition St. -

REGION 6 Address: Quintin Salas, Jaro, Iloilo City Office Number: (033) 329-6307 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: Dianne A

REGION 6 Address: Quintin Salas, Jaro, Iloilo City Office Number: (033) 329-6307 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: Dianne A. Silva Mobile Number: 0917 311 5085 Asst. Regional Director: Lolita V. Paz Mobile Number: 0917 179 9234 Provincial Office : Aklan Provincial Office Address : Linabuan sur, Banga, Aklan Office Number : (036) 267 6614 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Benilda T. Fidel Mobile Number : 0915 295 7665 Buying Station : Aklan Grains Center Location : Linabuan Sur, Banga, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Ruben Gerard T. Tubao Mobile Number : 0929 816 4564 Service Areas : Municipalities of New Washington, Banga, Malinao, Makato, Lezo, Kalibo Buying Station : Oliveros Warehouse Location : Makato, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Iris Gail S. Lauz Mobile Number : 0906 042 8833 Service Areas : Municipalities of Makato and Lezo Buying Station : Magdael Warehouse Location : Lezo, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Ruben Gerard T. Tubao Mobile Number : 0929 816 4564 Service Areas : Municipalities of Malinao and Lezo Buying Station : Ibajay Buying Station Location : Ibajay, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Iris Gail S. Laus Mobile Number : 0906 042 8833 Service Areas : Municipality of Ibajay Buying Station : Mobile Procurement Team - 5 Location : Team Leader : Cristine B. Penuela Mobile Number : 0929 530 3103 Service Areas : Municipalities of Malinao and Ibajay Provincial Office : Antique Provincial Office Address : San Fernando, San Jose, antique Office Number : (036) 540-3697 / 0927 255 8191 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Ma. Theresa O. Alarcon Mobile Number : 0917 596 1732 Buying Station : GID Camp Fullon Location : San Fernando, San Jose, Antique Warehouse Supervisor : Judy F. Devera Mobile Number : 0916 719 8151 Service Areas : Municipalities in Cental and Southern Antique Buying Station : GID Culasi Location : Caridad, Culasi Warehouse Supervisor : Ma. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

I PfV- A:Cr~qq0 :D;J b3 9 I I I FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCEPTANCE AND CONTINUATION I OFIUD A COMPARATIVE STUDY I PHILIPPINES I FmalReport I I ASIA & NEAR EAST OPERATIONS RESEARCH AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT I FAMILY PLANNING OPERATIONS RESEARCH I AND TRAINING (FPORT) PROGRAM PopulatIOn CouncIl, ManIla I m collaboratIOn with the Department of Health I USAID Contract No DPE-C-OO-90-0002-10 I StrategIes for Improvmg FamIly Plannmg ServIce DelIvery I July 1998 I I I I I I ACKNOWLEDGMENT I Tills project was conducted by Populatlon CouncIl-Mamla, m collaboratIOn wIth the Department of Health under the ANE ORiTA Project wIth support from the Office of I PopulatIOn Health and NutntIOn (OPHN), US Agency for International Development, Contract No DPE-3030-C-OO-90-0002-1 0 I PopulatIOn CouncIl, ManIla would hke to acknowledge the mdIvIduals and I mstltutIOns who helped m carrymg out thIS project • Dr Magdalena C Cab arab an, the head of the research team and the overall I coordmator ofthe study m ItS two study SItes, Mlsamls On ental and IloIlo • Dr Jayantl Tuladhar, PopulatIOn CouncIl, New Delln for ills techmcal aSSIstance m I the questIOnnaire deSIgn and data analYSIS for the modified SA used m tills study • Dr Josefina Cablgon for her asSIstance m data analYSIS and Mr FIono Argmllas ills I work m the data management and programmmg • The Research InstItute ofMmdanao Culture, as represented by Mrs Manlou Tabor, Operatlons Manager, who handled the admmlstratlve aspects of the project and the I recruItment of project staff • The SOCIal SCIence -

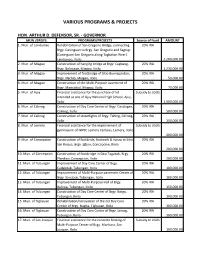

Various Programs & Projects

VARIOUS PROGRAMS & PROJECTS HON. ARTHUR D. DEFENSOR, SR. - GOVERNOR MUN./BRGYS. PROGRAMS/PROJECTS Source of Fund AMOUNT 1. Mun. of Lambunao Rehabilitation of San Gregorio Bridge, connecting 20% IRA Brgy. Caninguan to Brgy. San Gregorio and Sagcup (Caninguan-San Gregorio along Tagbakan River) Lambunao, Iloilo 2,200,000.00 2. Mun. of Miagao Construction of hanging bridge at Brgy. Cagbang- 20% IRA Brgy. Bolocaue, Miagao, Iloilo 1,230,000.00 3. Mun. of Miagao Improvement of footbridge of Sitio Buenapantao, 20% IRA Brgy. Naclub, Miagao, Iloilo 50,000.00 4. Mun. of Miagao Construction of the Multi-Purpose pavement of 20% IRA Brgy. Maricolcol, Miagao, Iloilo 70,000.00 5. Mun. of Ajuy Financial assistance for the purchase of lot Subsidy to LGUS intended as site of Ajuy National High School, Ajuy, Iloilo 1,000,000.00 6. Mun. of Calinog Construction of Day Care Center of Brgy. Caratagan, 20% IRA Calinog, Iloilo 500,000.00 7. Mun. of Calinog Construction of streetlights of Brgy. Tahing, Calinog, 20% IRA Iloilo 150,000.00 8. Mun. of Lemery Financial assistance for the improvement of Subsidy to LGUS gymnasium of NIPSC Lemery Campus, Lemery, Iloilo 400,000.00 9. Mun. of Concepcion Construction of footbride, footwalk & riprap at Sitio 20% IRA San Roque, Brgy. Igbon, Concepcion, Iloilo 200,000.00 10. Mun. of Concepcion Construction of footbridge in Sitio Tagabak, Brgy. 20% IRA Plandico, Concepcion, Iloilo 200,000.00 11. Mun. of Tubungan Improvement of Day Care Center of Brgy. 20% IRA Cadabdab, Tubungan, Iloilo 100,000.00 12. Mun. of Tubungan Improvement of Multi-Purpose pavement Center of 20% IRA Brgy. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register Summary 85 84 4 04-2015 301 B1 023545 1 -4 0 0 5 3818 29 22 4 05-2015 301 B1

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MAY 2015 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3818 023545 BACOLOD CITY HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 84 5 0 0 -4 1 85 3818 023547 BACOLOD CITY SUGARLANDIA PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 22 4 0 3 0 7 29 3818 023586 ILOILO HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 88 0 0 0 -16 -16 72 3818 023600 MOUNT KANLAON PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 85 15 0 3 -11 7 92 3818 023603 OCCIDENTAL NEGROS HOST PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 68 2 0 0 -18 -16 52 3818 029600 BACOLOD CITY CAPITOL PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 26 2 0 0 -1 1 27 3818 030211 BACOLOD CITY BACOLOD AIRPORT PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 21 10 0 1 -9 2 23 3818 031135 BACOLOD CITY MT KANLANDOG PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 56 5 0 0 -2 3 59 3818 031712 ILOILO CITY EXECUTIVE PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 32 0 0 0 -3 -3 29 3818 031713 POTOTAN PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 60 6 0 0 -6 0 60 3818 031888 CAPIZ L C PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 28 17 0 0 0 17 45 3818 033755 ILOILO FORT SAN PEDRO PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 18 0 0 0 0 0 18 3818 034135 BACOLOD KATIPUNAN PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 04-2015 11 0 0 0 0 0 11 3818 037381 ILOILO CITY INTEGRATED PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 43 8 0 0 -1 7 50 3818 041571 ILOILO CITY METRO PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 46 10 2 0 -2 10 56 3818 045379 BACOLOD TRADERS PHILIPPINES 301 B1 4 05-2015 28 5 0 0 0 5 33 3818 047751 ILOILO CITY PROFESSIONAL PHILIPPINES 301 B1 -

Biosecurity for Shrimp Farms

Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Aquaculture Department SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository http://repository.seafdec.org.ph 01 SEAFDEC/AQD Publications Brochures and flyers 2007 Biosecurity for shrimp farms Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center http://hdl.handle.net/10862/630 Downloaded from http://repository.seafdec.org.ph, SEAFDEC/AQD's Institutional Repository Farm personnel should: 3 When proven to be infected by WSSV or other shrimp viral diseases, eradicate hosts (shrimp Not have visited other shrimp culture sites or facilities stock and other crustaceans) mechanically and hold rearing within the past 24 hours water for at least a week. Sell the shrimp if big enough, but gather the remaining crustaceans and burn Change into a work uniform and foot gear before entry into areas where shrimp are raised Bear in mind though that any uncooked, infected shrimp or its washings are potential sources of the virus Under some conditions, shower in addition to changing clothes, prior to entering the shrimp Ideally, crusticide treatment should be applied to affected ponds production facilities before disinfection and release of water 4 SEAFDEC will report this disease outbreak to the Department of Agriculture Local Government Units (DA-LGU) 3 Monitor the presence of viruses by sending tissue samples regularly to a disease 5 DA-LGU will inform other farms in the locality diagnostic laboratory of the outbreak to prevent the spread of diseases DURING disease outbreak AFTER disease outbreak 1 Do not drain contaminated pond water To avoid recurrence: 2 Report immediately the disease outbreak 1 Review your operations. Did you do GMPs? Were the to either: biosecurity measures in place? Was your monitoring adequate? SEAFDEC Dumangas Brackishwater Station, Dumangas, Iloilo 2 Modify culture system (use of greenwater, reservoir; closed/ Telefax no.