“Casting Around”: Hitchcock's Absence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Press Kit With

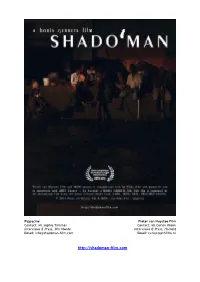

Pippaciné Pieter van Huystee Film Contact: Ms.Sophia Talamas Contact: Ms.Curien Kroon Interviews & Press, Worldwide Interviews & Press, Holland Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] http://shadoman-film.com SHADO’MAN Shot in Freetown, Sierra Leone 87 min, feature length documentary Available on DCP Original language Krio Subtitles English, French or Dutch LOGLINE A community of friends, each facing severe physical and psychological challenges, survives on the nocturnal streets of Freetown, Sierra Leone. The film delves deep into their life, telling a story of humanity and dignity in a world that otherwise offers little consolation. SYNOPSIS A bitter logic lies in the fact that those whom the society does not care to see are living by night. At the junction of Lightfoot-Boston and Wilberforce in downtown Freetown, Sierra Leone the streets of the city are covered in darkness. Only a few street lamps and flares of light from passing cars and motorcycles sporadically illuminate the Dantesque scenery. This is where a group of friends live. They call themselves the Freetown Streetboys, even though some women are among them. They each face enormous physical and psychological challenges. From early childhood when they endured the neglect and scorn of their parents until the present day, their life has been one of social abandonment by the world around them. With no place but the bleak and sleepless streets of the capital city, they are condemned to a life of begging. Shado’man is a cinematic journey undertaken by the filmmaker together with the ‘Streetboys’: Suley, Lama, David, Alfred, Shero and Sarah. -

Johan Van Der Keuken

HIVER 2018 RÉTROSPECTIVE JOHAN VAN DER KEUKEN DU COURT, TOUJOURS NOUVELLES ÉCRITURES DOCUMENTAIRES 1 2 ÉDITO À partir de janvier 2018, la Bibliothèque Organisée en trois grandes saisons publique d’information s’engage dans proposant chacune un cycle phare, un pari un peu fou : proposer chaque la programmation de la Bpi aura jour, aux curieux, aux cinéphiles, à tous, pour objectifs d’accompagner et de venir voir des films documentaires diffuser la création contemporaine, dans les salles du Centre Pompidou. de montrer les films de patrimoine Des films venus du monde entier, sur leur support d’origine et en version des grands classiques aux dernières restaurée, de valoriser et interroger créations, des films pour se donner le des corpus artistiques et thématiques, temps de regarder et penser le monde, à commencer au 1er trimestre 2018 ensemble, au cinéma. par une rétrospective consacrée au cinéaste néerlandais Johan van C’est toute l‘ambition de l’incarnation der Keuken. La cinémathèque du parisienne d’un projet à part, La documentaire à la Bpi proposera cinémathèque du documentaire. aussi des rendez-vous réguliers : courts métrages, nouvelles écritures, En résonance avec la société, ses travaux en cours, fenêtre sur festivals, espoirs, ses rêves, ses inquiétudes, avant-premières…, ainsi qu’un volet la création documentaire connaît d’éducation à l’image destiné aux une effervescence extraordinaire. scolaires. Elle attire un public toujours plus nombreux. Au cinéma, à la télévision, Le cinéma documentaire a toujours sur les réseaux numériques, elle été au cœur de l’identité de la Bpi qui enrichit chaque jour un fonds d’une fut en 1977 la première bibliothèque exceptionnelle diversité de regards, multimédia en France. -

De Grote Vakantie / Die Großen Ferien

7 DE GROTE VAKANTIE Die Großen Ferien The Long Holiday Regie: Johan van der Keuken Land: Niederlande 1999. Produktion: Pietervan Huystee Film & Synopsis TV. Regie, Kamera: )ohan van der Keuken. Ton: Noshka van der In October 1998, Johan van der Keuken called his doc - Lely. Schnitt: Menno Boerema. tor (the head of radiotherapy) at the Academic Hospital Format: 35mm, 1:1.66, Farbe. Länge: 145 Minuten, 25 Bilder/Sek. in Utrecht from Paris and heard that he only had a few- Uraufführung: Januar 2000, Filmfestival Rotterdam. years to live. Prostate cancer cells had taken hold in his Sprachen: Niederländisch, tibetanis< h, englisch, französisi h. son- body. ray, moree. Van der Keuken has travelled the world for years with Ins Drehorte: Nepal, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Brasilien, USA und wife Nosh van der Lely. She held the microphone and die Niederlande. recorder, he wielded the camera. Together they decided Weltvertrieb: Ideale Audience Distribution (Susanna Scott), 13 to spend the rest of their precious time looking and lis• rue Portefoin, 75003 Paris, Frankreich. Tel.: (33-1) 42 77 89 70. tening. At Christmas they set off for Bhutan. Johan van Fax: (33-1) 42 77 36 56. E-mail: [email protected] der Keuken regarded the film they were embarking on as a chronicle of his own view of the world, made all the Inhalt more urgent by his own mortality. Later in the film - and Im Oktober 1998 rief Johan van der Keuken seinen Arzt (den in his life - things take a turn for the better, when Johan ( hefarzt der Abteilung Strahlentherapie) an der Universitätsklinik finds a new medicine in the United States that drastically in Utrecht von Paris aus an und erfuhr, daß er nur noch einige increases his chanc es of sur\ iv al. -

L'œuvre De Johan Van Der Keuken Et Son Contexte : Contre Le Documentaire, Tout Contre

L'œuvre de Johan van der Keuken et son contexte : contre le documentaire, tout contre. Par Robin Dereux La position de Johan van der Keuken par rapport au genre documentaire ne peut pas se résumer en une phrase. Elle est complexe, variable selon les époques, et lui-même donne régulièrement l’impression d’entretenir une certaine ambiguïté par rapport à cette question. D’autre part, on sent bien que ce qu’il expose dans les entretiens avec la presse repose largement sur des malentendus et sur l’attente de son interlocuteur. Les historiens y verront peut-être une attitude paradoxale: van der Keuken critique souvent le genre mais inscrit aussi ses films dans des “festivals documentaires”. S’il cite souvent en référence des cinéastes emblématiques (Leacock par exemple), et d’autres qui ont pu, à un moment ou à un autre, être assimilés au “documentaire”, bien que leur travail transcende les genres (comme Ivens ou Rouch), il se réfère au moins autant à des cinéastes de fiction (Hitchcock, Resnais), et parfois également à des cinéastes expérimentaux (Jonas Mekas, Yervant Gianikian et Angela Ricci Luchi). Tout est donc question de point de vue, et van der Keuken donne souvent l’impression, dans ses textes et entretiens, de ménager les différentes interprétations. Son attitude, à la fois volontaire et douce, l’amène parfois au sentiment d’être incompris, quand la distance est trop grande entre sa recherche et les questions qui lui sont posées. Il ne lui reste alors plus qu’à répéter toujours la même phrase: “on ne peut pas se contenter d’une description primaire du réel”, que l’on peut interpréter comme une mise en garde contre l’assimilation trop rapide à un genre avec lequel il se débat. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics Rusch, L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rusch, L. (2016). "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 "Our Subcultural Shit-Music": Dutch Jazz, Representation, and Cultural Politics ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op dinsdag 17 mei 2016, te 14.00 uur door Loes Rusch geboren te Gorinchem Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. -

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de kunsten: audiovisuele kunsten Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Doctor of Arts: Audiovisual Arts Academic year 2017- 2018 Doctorandus: Stoffel Debuysere Promotors: Prof. Dr. Steven Jacobs, Ghent University, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Dr. An van. Dienderen, University College Ghent School of Arts Editor: Rebecca Jane Arthur Layout: Gunther Fobe Cover design: Gitte Callaert Cover image: Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep (1977). Courtesy of Charles Burnett and Milestone Films. This manuscript partly came about in the framework of the research project Figures of Dissent (KASK / University College Ghent School of Arts, 2012-2016). Research financed by the Arts Research Fund of the University College Ghent. This publication would not have been the same without the support and generosity of Evan Calder Williams, Barry Esson, Mohanad Yaqubi, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Sarah Vanhee, Christina Stuhlberger, Rebecca Jane Arthur, Herman Asselberghs, Steven Jacobs, Pieter Van Bogaert, An van. Dienderen, Daniel Biltereyst, Katrien Vuylsteke Vanfleteren, Gunther Fobe, Aurelie Daems, Pieter-Paul Mortier, Marie Logie, Andrea Cinel, Celine Brouwez, Xavier Garcia-Bardon, Elias Grootaers, Gerard-Jan Claes, Sabzian, Britt Hatzius, Johan Debuysere, Christa -

Johan Van Der Keuken's Global Amsterdam

7. Form, Punch, Caress: Johan van der Keuken’s Global Amsterdam Patricia Pisters After many years of travelling the world with his camera, in the early 1990s doc- umentary filmmaker Johan van der Keuken expressed his surprise at the many changes that had taken place in his hometown of Amsterdam: ‘To tell the truth, I didn’t recognize all the cultures that had settled there in the past few decades, nor the subcultures and “gangs” that had sprung up’. At the same time, he realized that ‘my city, Amsterdam, was the place where everything that I could see eve- rywhere else was represented’, and that in order to understand the world, all he needed to do was direct his camera to his own neighbourhood (van der Keuken, qtd. in Albera 2006, 16). This is when he decided to make Amsterdam Global Village, a four-hour documentary filmed in Amsterdam in the mid-1990s. He made it in his characteristic fashion, travelling through the city with his camera, visiting some of its inhabitants in their homes, listening to their stories, and some- times following them to places elsewhere in the world – but always to return. Johan van der Keuken captured Amsterdam with his camera from the very start of his career, following his studies at the Institut des Hautes Études Ciné- matographiques (IDHEC) in Paris in the late 1950s. As he regularly applied his camera to Amsterdam through several decades, his work forms a rich – and very personal – archive of historical impressions of an ever-changing city. Looking at some key films situated in Amsterdam, such as Beppie (1965), Four Walls (1965), Iconoclasm – A Storm of Images (1982), and Amsterdam Global Village (1996), this essay presents a double portrait of the Amsterdam corpus within van der Keuken’s oeuvre. -

Virtuose Et Moderne · Photo Bernard Prim LE GENOU DE CLAIRE

janvier - février 2018 · NOS PHOTOS DE TOURNAGE · ANNE-MARIE MIÉVILLE · PROJECTIONS FAMILLE · FILMS NOIRS, FILMS D’ANGOISSE · COMBIEN D’ENTRE NOUS ? : LES FILMS DE GHASSAN SALHAB 18 janvier — 5 février virtuose et moderne Photo Bernard Prim · LE GENOU DE CLAIRE CINEMATHEQUE.QC.CA RENSEIGNEMENTS HEURES D’OUVERTURE INFO-PROGRAMMATION : CINEMATHEQUE.QC.CA ou 514.842.9763 BILLETTERIE : DROITS D’ENTRÉE1 : ADULTES 10 $ LUNDI À VENDREDI DÈS 10 h 4-16 ANS, ÉTUDIANTS ET AÎNÉS 9 $2 · 1-3 ANS GRATUIT SAMEDI ET DIMANCHE DÈS 14 h FAMILLE 3 PERSONNES 20 $ · FAMILLE 4 PERSONNES 25 $ EXPOSITIONS : MEMBRE ET ABONNEMENT RÉGULIER3 : 1 PERSONNE 120 $ / 1 AN LUNDI À VENDREDI DE MIDI À 21 h ABONNEMENT ÉTUDIANT3 : 1 PERSONNE 99 $ / 1 AN SAMEDI ET DIMANCHE DE 14 h À 21 h PROGRAMMATION ART ET ESSAI : MÉDIATHÈQUE GUY-L.-COTÉ : 12 $ / TARIF RÉGULIER · 9 $ / TARIF AINÉS, ÉTUDIANTS, MEMBRES ET ABONNÉS MARDI À VENDREDI DE 9 h 30 À 17 h EXPOSITIONS : ENTRÉE LIBRE BAR SALON : 1. Taxes incluses. Le droit d’entrée peut différer dans le cas de certains programmes spéciaux. LUNDI DE 10 h 15 À 18 h 2. Sur présentation d’une carte d’étudiant ou d’identité. 3. Accès illimité à la programmation régulière. MARDI À VENDREDI DE 10 h 15 À 22 h CINÉMATHÈQUE QUÉBÉCOISE : 335, boul. de Maisonneuve Est, Montréal (Québec) Canada H2X 1K1 · Métro Berri-UQAM Distribué par Publicité sauvage DESIGN AGENCE CODE Imprimé au Québec sur papier québécois recyclé à 100 % (post-consommation) MA NUIT CHEZ MAUD Rohmer, virtuose et moderne Photo Bernard Prim LE GENOU DE CLAIRE ·: DU 18 JANVIER AU 5 FÉVRIER :· Au début des années 1960, le futur cinéaste Barbet Schroeder a créé pour Eric Rohmer la société de production des Films du Losange, tou- jours active aujourd’hui, accompagnatrice de nombreux cinéastes mar- quants, dont Michael Haneke. -

06 Bacque¦Ü Du Cine¦Üma E Final

From Documentary Film to Video Essay: The Invention of Screen Realism Bertrand Bacqué From its earliest days, documentary cinema has dealt with history, both on a small and a large scale, with identity, intimacy, and that which can best be described as otherness. When Louis Lumière filmed his family, his factory, or a train pulling into the station at La Ciotat, he invented at one and the same time the home movie, the publicity film, and the news reel. Almost immediately, however, this Lyon businessman became more ambitious, sending cameramen to film important events such as the coronation of Czar Nicolas II in May 1896. This was to result in the first example of censorship in the history of cinema.1 While the origins of cinema and filmed documentaries are generally attributed to the Lumière brothers, the name of Méliès, better known for his Voyage dans la lune and Quatre cents farces du diable, is frequently forgotten in this context. His works of “reconstituted actuality” include The Dreyfus Affair (1899), one of the first politically committed films in the history of cinema, in which Méliès defends the unjustly accused French officer, setting out the events that had taken place a short time before the invention of cinematography. Similarly and so as not to get in the way of the ceremony, Méliès filmed, in advance, a reconstruction of the coronation of Edward VII in his studios outside Paris. The day after the coronation, the delighted king declared: “I recognized myself immediately, and the queen too. If I were not sure of the contrary, I should have said we were watching ourselves.”2 Even 1 Two days after the official ceremonies, the czar appeared before the people. -

Coffrets Johan Van Der Keuken : Le Testament D'un Cinéaste

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 21:22 24 images Coffrets Johan van der Keuken Le testament d’un cinéaste Robert Daudelin Court métrage Québec Numéro 131, mars–avril 2007 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/12734ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (imprimé) 1923-5097 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Daudelin, R. (2007). Coffrets Johan van der Keuken : le testament d’un cinéaste. 24 images, (131), 50–52. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2007 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ CHRONIQIIF Coffrets Johan van der Keuken Le testament d'un cinéaste par Robert Daudelin ien qu'il ait parfois eu l'impres sion de « prêcher à des conver tis », retrouvant les mêmes fidè les spectateurs à chaque nouvelle visitBe à Montréal, à Toronto, à Buffalo, à Minneapolis, à Berkeley, à Bruxelles ou à Paris, Johan van der Keuken, compte tenu du créneau exigeant (documentaires/essais) où se situent ses films, n'en était pas moins un cinéaste reconnu au moment de sa dis parition, en janvier 2001. -

64-71 Hitchcock.Qxp

Master of SUSPENSE Alfred Hitchcock always said shooting was his least favorite part of the job. But you’d never know it to see him engaged in the process of directing in this series of rare set shots. FEATHERED FRIENDS: (left) Even the non-actors sit up and take direction along with the cast in The Birds (1963). Hitchcock disliked shooting on location and much of the film was shot in the studio. (above) Cary Grant is a gambler who may or may not be planning to kill his new wife Joan Fontaine in Suspicion (1941), Hitchcock’s first film as a director/producer. 64 dga quarterly Photos: (above) Universal/MPTV.net; (right) AMPAS dga quarterly 65 MURDER MOST FOUL: Staged around a dead body concealed in a trunk during a dinner party, Rope (1948) was shot as a series of four- to-ten-minute takes, with only two intentionally visible cuts. It was the director’s first color film. LISTEN UP: Hitchcock monitors the sound in Blackmail (1929), generally considered the first British talkie. Much of the picture was orig- inally filmed silent and then re-shot with the advent of sound. SUNBLOCK: Hitchcock seems out of place instructing Grace Kelly how to get a tan on the beach in Nice for the Riviera caper, To Catch a Thief (1955). Photos: (top and opposite) AMPAS; (bottom) DGA Archives 66 dga quarterly VOYEUR: Injured photographer JUST SO: Gregory Peck plays a Jimmy Stewart imagines a murder lawyer defending a woman accused plot while peering into the courtyard of murdering her husband in The of his building in Rear Window Paradine Case (1947). -

Entretien Avec Johan Van Der Keuken Michel Coulombe

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 16:10 Ciné-Bulles Le cinéma d’auteur avant tout Entretien avec Johan van der Keuken Michel Coulombe Volume 5, numéro 4, mai–juillet 1986 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/34463ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (imprimé) 1923-3221 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce document Coulombe, M. (1986). Entretien avec Johan van der Keuken. Ciné-Bulles, 5(4), 20–23. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 1986 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Entretien avec Johan van der Keuken études cinématographiques (I.D.H.E.C.) à Paris de 1956 à 1958. On y enseignait sur tout le cinéma classique, avec une forte divi sion du travail. Je me sentais un peu mal à l'aise là-dedans, aussi ai-je continué à faire de la photographie. J'ai commencé par faire de petits films, caméra à la main. Avec James Michel Coulombe Blue, documentariste américain — décédé depuis — j'ai tourné, Paris à l'aube.