The King's Choice – 10Th of April 1940 Alf R. Jacobsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norges Postvesen 1932

OGES OISIEE SAISIKK I 1 OGES OSESE 193 (Statistique postale pour l'année 1932) Ugi a EAEMEE O AE SØA IUSI ÅEK OG ISKEI POSTSTYRET OSLO I KOMMISJON HOS H. ASCHEHOUG & CO. 1933 For årene 1884-1899, se Norges Offisielle Statistikk, rekke III. For årene 1900-1904, se rekke IV, senest nr. 120. For årene 1905-1912, se rekke V, senest nr. 204. For årene 1913-1919, se rekke VI, senest nr. 180. For året 1920, se rekke VII, nr. 18. For året 1921, se rekke VII, nr. 50. For aret 1922, se rekke VII, nr. 87. For aret 1923, se rekke VII, nr. 126. For året 1924, se rekke VII, nr. 171. For året 1925, se rekke VII, nr. 197. For året 1926, se rekke VIII, nr. 27. For året 1927, se rekke VIII, nr. 61. For aret 1928, se rekke VIII, nr. 95. For året 1929. se rekke VIII, nr. 126. For året 1930, se rekke VIII, nr. 159. For aret 1931, se rekke VIII, nr. 187. J. Chr. Gundersen Boktrykkeri, Oslo Innholdsfortegnelse. Side Fransk innholdsoversikt V Tekst: I. Innledning 1 II. Poststeder og postkasser 3 III. Personale og undervisningsvesen IV. Postførsel 13 V. Posttrafikk 22 VI. Økonomiske resultater 42 VII. Postlov, postoverenskomster og postreglement 53 VIII. Poststyre og postdistrikter 54 IX. Pensjons- og understøttelseskasser 55 X. Internasjonal poststatistikk 55 Tabeller: Tab. 1. Almindelige og rekommanderte brevpostforsendelser, verdibrev, pakker, aviser og postopkrav 56 • 2. Postanvisninger 68 D 3. Post til utlandet 74 • 4. Post fra utlandet . 76 • 5. De enkelte poststeders frimerkesalg og avsendte brevpostmengde 78 • 6. Poststeder og tjenestemenn etc. -

Takstprotokoller 2008 Utg 2 M Foto

Jernbaneverket. Biblioteket Takstprotokoller Katalog over dokumenter for ekspropriasjon av grunn for jernbane mv. Tore H Vigerust Oslo 2008 1 INNHOLD Dovrebanen. Hovedbanen (Christiania-Eidsvold). 1854-1960………………….. 4 Rørosbanen i Hedmark amt/fylke og i Akershus. Hamar-Elverum-Jernbanen, Grundset-Aamot Jernbanen, Støren-Aamot Jernbaneanlæg, Hamar-Eidsvoldbanen (Hedemarksbanen). 1858-2008 …………………………………… 6 Kongsvingerbanen. Solørbanen (Kongsvinger-Flisenbanen, Flisen-Elverumbanen). Vestmarkalinjen (Skotterud-Vestmarka). Urskog-Hølandsbanen. 1858-1974…………………………………………………. 9 Østfoldbanen (Sydbanen, Smaalensbanen, Østre Linie). 1874-1989……………… 13 Dovrebanen. Hamar-Selbanen. Otta-Dombåsbanen. Raumabanen. 1891-1950………………………………………………………….. 18 Gjøvikbanen. Valdresbanen (Eina-Fagernes). Alnabanen, Forbindelsen Roa-Hønefoss (Bergensbanen østenfjelds). Røykenvikbanen, Skreiabanen (Reinsvollbanen). 1896-1960………………………………………… 22 Drammenbanen (Kristiania - Drammen). 1870-1986…………………………….. 26 Bergensbanen. Randsfjordbanen. 1863-1921……………………………………… 27 Sørlandsbanen. Vestfoldbanen. Randsfjordbanen (Hokksund-Kongsberg). Bratsbergbanen (Nordagutu-Porsgrunn). 1870-1951…………………………….. 28 Alle fotografiene viser takstprotokoller i bibliotekets magasin. Foto: Stein Eriksen, JBV. 2 Takstprotokollene består i hovedsak av autoriserte (og uautoriserte) utskrifter av ekspropriasjonstakster fra rettsforhandlingene på de lokale tingene - ført av sorenskriverne eller byfogdene - med overtakster, undertakster, ettertakster, konduktør- og kartforretninger, foreløpige og endelige -

Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Knut Kristian Langva Døscher German Reprisals in Norway During the Second World War Master’s thesis in Historie Supervisor: Jonas Scherner Trondheim, May 2017 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Preface and acknowledgements The process for finding the topic I wanted to write about for my master's thesis was a long one. It began with narrowing down my wide field of interests to the Norwegian resistance movement. This was done through several discussions with professors at the historical institute of NTNU. Via further discussions with Frode Færøy, associate professor at The Norwegian Home Front Museum, I got it narrowed down to reprisals, and the cases and questions this thesis tackles. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Scherner, for his guidance throughout the process of writing my thesis. I wish also to thank Frode Færøy, Ivar Kraglund and the other helpful people at the Norwegian Home Front Museum for their help in seeking out previous research and sources, and providing opportunity to discuss my findings. I would like to thank my mother, Gunvor, for her good help in reading through the thesis, helping me spot repetitions, and providing a helpful discussion partner. Thanks go also to my girlfriend, Sigrid, for being supportive during the entire process, and especially towards the end. I would also like to thank her for her help with form and syntax. I would like to thank Joachim Rønneberg, for helping me establish the source of some of the information regarding the aftermath of the heavy water raid. I also thank Berit Nøkleby for her help with making sense of some contradictory claims by various sources. -

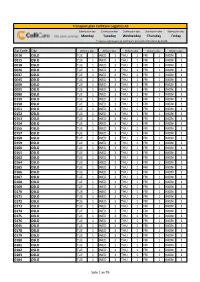

Zip Code City 0010 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1

Transport plan ColliCare Logistics AS Submission day Submission day Submission day Submission day Submission day Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday *requires submission to ColliCare's terminal at Skedsmo by 16:00 Zip Code City Delivery day Delivery day Delivery day Delivery day Delivery day 0010 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0015 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0018 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0026 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0037 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0045 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0050 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0055 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0080 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0139 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0150 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0151 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0152 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0153 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0154 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0155 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0157 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0158 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0159 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0160 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0161 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0162 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0164 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0165 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0166 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0167 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0168 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0169 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0170 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0171 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0172 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 THU 1 FRI 1 MON 1 0173 OSLO TUE 1 WED 1 -

En Samtale Med Nils Ringnes Om Jakt Og Høst Og Skaperverk Og Sånn

www.stangemenighet.no Nr. 3 – 2013 – 66. årgang En samtale med Nils Ringnes om jakt og høst og skaperverk og sånn... side 4 Ble konfirmert og skal bli konfirmert side 13 og 21 Internasjonal kaf é side 15 tangenihedmark.com side 11 Det er høst Det er høst. Kornåkrene står gule. I hagene bugner det av frukt og bær, og det er overflod av elg i skogen. Bøndene tresker kornet sjøl om det er et magert år. Snart er det elgjakt, og fortsatt er den en del av matauka her hos oss; - ikke kun en fritidssys - sel. Barnehagen på Tangen feirer høsttakkefesten i kirken og går tilba - ke og lager grønnsakssuppe. Skolen høster inn og lager syltetøy og andre produkter som de selger på høstmar - kedet sitt. Noen spør om hvorfor vi skal holde på med dette? Vi kan jo kjøpe syltet - øy, brød og biff på butikken. Og hvorfor skal vi bruke penger på subsi - dier til landbruket når andre land kan produsere maten mye billigere? Vi er da et moderne samfunn som tjener godt på oljen og kan importere den maten vi trenger. Det handler om verdier, om å ta på alvor det forvalteransvaret vi har fått. ”Alt som lever og rører seg skal dere r ha å spise. Som jeg ga dere de grønne e plantene, gir jeg dere nå alt dette”. (1. d e Mos. 9,3). Nøysomhet og sjølberging l har vært nødvendig her i landet. Det er ikke mange år siden, og det kan bli slik igjen. Derfor er det avgjørende at vi lærer dette videre til nye generasjoner; - kunnskapen om hvor maten kommer fra og hvordan vi utnytter ressursene på en bærekraftig måte. -

Søknad Fra Bjørg Nordset, Lesjaverk, Om Transport Med Snøskuter Til Bu Ved Vangsvatnet I Dalsida Landskapsvernområde 2020-2023

Postadresse Besøksadresse Kontakt Postboks 987 Norsk villreinsenter nord Sentralbord +47 61 26 60 00 2604 Lillehammer Hjerkinnhusvegen 33 Saksbehandler +47 61 26 62 08 2661 Hjerkinn [email protected] www.nasjonalparkstyre.no/dovrefjell Bjørg Nordset Romsdalsvegen 3697 2667 Lesjaverk E-postadresse: [email protected] Delegert sak nr. 147-2019 SAKSBEHANDLER: LARS BØRVE ARKIVSAK - ARKIVKODE: 2019/20953 - 432.2 DATO: 12.12.2019 Søknad fra Bjørg Nordset, Lesjaverk, om transport med snøskuter til bu ved Vangsvatnet i Dalsida landskapsvernområde 2020-2023 Dokumenter 25.11.2019: Søknad fra Bjørg Nordset, Lesjaverk, om transport med snøskuter til bu ved Vangsvatnet i Dalsida landskapsvernområde 2020-2023. 29.11.2019: E-post fra Lesja kommune til Dovrefjell nasjonalparkstyre – oversending av søknad for behandling. Opplysninger om søknaden / saksopplysninger Bjørg Nordset, Romsadalsvegen 3697, 2667 Lesjaverk, søker 25.11.2018 om tillatelse til transport av ved og proviant mm. med snøskuter (leiekjører) til bu (Oddbu) ved Vangsvatnet i Dalsida landskapsvernområde 2020-2023, og byggeavfall tilbake. Kjørerute er Lesjaverk / Fjellvegen – Merrabotn - Vangsvatnet. Det søkes om 1 tur (tur-retur) pr. år. Regler og retningslinjer for saksbehandlingen Regler og retningslinjer for saksbehandlingen går bl.a. fram av: - Verneforskrift for Dalsida landskapsvernområde av 3. mai 2002. - Naturmangfoldloven av 19. juni 2009. - Forvaltningsplan for verneområdene på Dovrefjell, vedtatt 8. februar 2006. - Rundskriv om forvaltning av verneforskrifter, utgitt av Miljødirektoratet i 2014. Formålet med Dalsida landskapsvernområde er bl.a. å ta vare på et sammenhengende leveområde for villreinen i Snøhetta-området, jf. verneforskriften § 2. I Dalsida landskapsvernområde er motorferdsel med snøskuter vanligvis ikke tillatt, jf. verneforskriften § 3 pkt. 5.1 og 5.2, men forvaltningsmyndigheten kan gi tillatelse til bl.a. -

Søknad Fra Sigmund Kolstad, Lesjaverk, Om Transport Av Materialer M.M

Postadresse Besøksadresse Kontakt Postboks 987 Norsk villreinsenter nord Sentralbord +47 61 26 60 00 2604 Lillehammer Hjerkinnhusvegen 33 Saksbehandler +47 61 26 62 08 2661 Hjerkinn [email protected] www.nasjonalparkstyre.no/dovrefjell Sigmund Kolstad Romsdalsvegen 3589 2667 Lesjaverk Delegert sak nr. 093-2018 SAKSBEHANDLER: LARS BØRVE ARKIVSAK - ARKIVKODE: 2018/1372 - 432.2 DATO: 21.06.2018 Søknad fra Sigmund Kolstad, Lesjaverk, om transport av materialer m.m. med traktor til seter på Kvernslåe i Dalsida landskapsvernområde i 2018 Dokumenter 27.02.2018: Søknad fra Sigmund Kolstad, Lesjaverk, om transport med traktor til seter på Kvernslåe i Dalsida landskapsvernområde i 2018. 01.03.2018: E-post fra Lesja kommune til Dovrefjell nasjonalparkstyre – Oversending av søknad for behandling. 24.04.2018: Møtebok for sak nr. 10-2018 i Dovrefjell nasjonalparkstyre 09.04.2018: Søknad fra Sigmund Kolstad, Lesjaverk, om transport med traktor til seter på Kvernslåe i Dalsida landskapsvernområde i 2018. 08.06.2018: Møtebok for sak nr. 41-18 i Forvaltningsstyret i Lesja kommune 04.06.2018: Søknad om barmarkskjøring til Kvernslåe – Sigmund Kolstad. Opplysninger om søknaden / saksopplysninger Sigmund Kolstad, Romsdalsvegen 3589, 2667 Lesjaverk, søker 27.02.2018 om tillatelse til transport av materialer og redskaper m.m. med traktor, inntil 2 turer (tur-retur), langs gamle kjørespor mellom Fjellvegen på Lesjaverk og seter på Kvernslåe i Dalsida landskapsvern- område i tiden 15.06.-20.08.2018, og transport av bygningsavfall m.m. tilbake. Kart 1: Kart over området mellom Fjellvegen og Kvernslåe (Kvannslåe lokalt). Blå stiplet linje er kjøresporene som det søkes om å bruke. Grønn linje er grensa for Dalsida landskapsvernområde. -

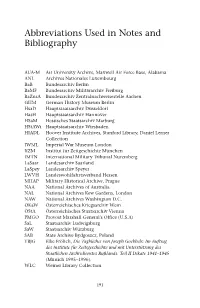

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

For Rettssikkerhet Og Trygghet I 200 År. Festskrift Til Justis

For rettssikkerhet og trygghet i 200 år FESTSKRIFT TIL JUSTIS- OG BEREDSKAPSDEPARTEMENTET 1814–2014 REDAKTØR Tine Berg Floater I REDAKSJONEN Stian Stang Christiansen, Marlis Eichholz og Jørgen Hobbel UTGIVER Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet PUBLIKASJONSKODE G-0434-B DESIGN OG OMBREKKING Kord Grafisk Form TRYKK 07 Media AS 11/2014 – opplag 1000 INNHOLD FORORD • 007 • HISTORISKE ORGANISASJONSKART • 008 • PER E. HEM Justisdepartementets historie 1814 – 2014 • 010 • TORLEIF R. HAMRE Grunnlovssmia på Eidsvoll • 086 • OLE KOLSRUD 192 år med justis og politi – og litt til • 102 • HILDE SANDVIK Sivillovbok og kriminallovbok – Justisdepartementets prioritering • 116 • ANE INGVILD STØEN Under tysk okkupasjon • 124 • ASLAK BONDE Går Justisdepartementet mot en dyster fremtid? • 136 • STATSRÅDER 1814–2014 • 144 • For rettssikkerhet og trygghet i 200 år Foto: Frode Sunde FORORD Det er ikke bare grunnloven vi feirer i år. Den bli vel så begivenhetsrike som de 200 som er gått. 07 norske sentraladministrasjonen har også sitt 200- Jeg vil takke alle bidragsyterne og redaksjons- årsjubileum. Justisdepartementet var ett av fem komiteen i departementet. En solid innsats er lagt departementer som ble opprettet i 1814. Retts- ned over lang tid for å gi oss et lesverdig og lærerikt vesen, lov og orden har alltid vært blant statens festskrift i jubileumsåret. viktigste oppgaver. Vi som arbeider i departementet – både embetsverket og politisk ledelse – er med God lesing! på å forvalte en lang tradisjon. Vi har valgt å markere departementets 200 år med flere jubileumsarrangementer gjennom 2014 og med dette festskriftet. Her er det artikler som Anders Anundsen trekker frem spennende begivenheter fra departe- Statsråd mentets lange historie. Det er fascinerende å følge departementets reise gjennom 200 år. -

United States of America V. Erhard Milch

War Crimes Trials Special List No. 38 Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 1975 Special List No. 38 Nuernberg War Crimes Trials Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch Compiled by John Mendelsohn National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1975 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data United States. National Archives and Records Service. Nuernberg war crimes trial records. (Special list - National Archives and Records Service; no. 38) Includes index. l. War crime trials--N emberg--Milch case,l946-l947. I. Mendelsohn, John, l928- II. Title. III. Series: United States. National Archives and Records Service. Special list; no.38. Law 34l.6'9 75-6l9033 Foreword The General Services Administration, through the National Archives and Records Service, is· responsible for administering the permanently valuable noncurrent records of the Federal Government. These archival holdings, now amounting to more than I million cubic feet, date from the <;lays of the First Continental Congress and consist of the basic records of the legislative, judicial, and executive branches of our Government. The presidential libraries of Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson contain the papers of those Presidents and of many of their - associates in office. These research resources document significant events in our Nation's history , but most of them are preserved because of their continuing practical use in the ordinary processes of government, for the protection of private rights, and for the research use of scholars and students. -

Marknader Og Handelsvegar 1600-1800

GUDBRANDSDALSSEMINARET 26.01.2011 Marknader og handelsvegar 1600-1800 Av Ivar Teigum I ein av utstillingssalane I Victoria & Albert-museet I London heng eit stort biletteppe som var kjøpt I Vågå I 1884.1 teppet skal vera vove i den første delen av 1600-talet. I Nord- Gudbrandsdalen var det fleire verkstader som dreiv med veving både av dobbeltvev og biletvev på denne tida. Motiva på biletteppa er oftast bibelske, opphavet til utforminga var gjerne henta frå grafiske blad omsette av reisande seljarar. Motiva vart sidan tekne opp att meir og mindre fritt av andre vevarar som heller ikkje trong vera så støe på dei bibelske forteljingane. Kanskje var dei meir opptekne av den tekniske utforminga av bileta, komposisjonen, og av sjølve kledraktene nytta av dei fornemme personane som tilskodaren ville møte. Biletteppet i V&A kan vi gjerne lesa som ein teikneserie. Dominerande midt i det øvre feltet møter vi engelen Gabriel der han forkynner for Maria at ho skal føde eit barn. Til venstre i feltet har Maria gått til systera Elisabet for å fortelja kva som har hendt. Til høgre i feltet møter vi dei tre vise menn som kjem for å helse Jesusbatnet i Betlehem. I det nedre feltet har vi ei inndeling vertikalt. Til høgre får tilskodaren vera vitne til ein scene frå det populære motivet “Herodes gjestebod” (Matt. 14). I den venstre delen har dotter til Herodes fått oppfylt ynsket om å få servert hovudet til døyparen Johannes på eit fat. Dei store biletteppa, over meteren breie og nær to meter lange, fortel om ein elite i norddalsbygdene på 1600- og 1700-talet.