'Pants to Poverty'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 - Scottishleftreview Issue 100 July/August 2017 2 - Scottishleftreview Issue 100 July/August 2017 Feedback

1 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 100 July/August 2017 2 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 100 July/August 2017 feedback comment Where we are now ay didn’t quite end in June situation has afflicted the SNP – still an election campaign, under which but her mantra of providing the biggest party by seats and votes reporting had to be more balanced, M‘strong and stable’ in Scotland but looking and feeling a Labour’s pledge to govern for the leadership turned into the actuality lot like Labour after its involvement reviewsmany and not the few resonated of being ‘weak and wobbly’ while in the ‘Better Together’ campaign – widely. Jeremy Corbyn was more at Corbyn went from being (allegedly) somewhat dejected and on the back home and a much better performer unelectable and an electoral liability foot. at the countless mass street rallies into something akin to a conquering than in the Westminster chamber. hero – certainly if his reception at Serious left analysis must start And, Labour was able to create its UNISON annual conference and by asking two fundamental own direct link to voters, especially Glastonbury were anything to go by. questions, namely, why did Labour younger ones, via social media Just as with after the independence do much better than any of the without being reliant upon the referendum in September 2014, it polls (including its own) indicated mainstream media. Its organisation seemed that the vanquished were it would, and why did Labour not of activists especially via a dedicated actually the victors. But there are actually win? The exposure of app used by Momentum in also other historical parallels to Theresa May as weak and wobbly particular was also notable. -

Putin's Useful Idiots

Putin’s Useful Idiots: Britain’s Left, Right and Russia Russia Studies Centre Policy Paper No. 10 (2016) Dr Andrew Foxall The Henry Jackson Society October 2016 PUTIN’S USEFUL IDIOTS Executive Summary ñ Over the past five years, there has been a marked tendency for European populists, from both the left and the right of the political spectrum, to establish connections with Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Those on the right have done so because Putin is seen as standing up to the European Union and/or defending “traditional values” from the corrupting influence of liberalism. Those on the left have done so in part because their admiration for Russia survived the end of the Cold War and in part out of ideological folly: they see anybody who opposes Western imperialism as a strategic bedfellow. ñ In the UK, individuals, movements, and parties on both sides of the political spectrum have deepened ties with Russia. Some individuals have praised Putin and voiced their support for Russia’s actions in Ukraine; others have travelled to Moscow and elsewhere to participate in events organised by the Kremlin or Kremlin-backed organisations; yet more have appeared on Russia’s propaganda networks. Some movements have even aligned themselves with Kremlin-backed organisations in Russia who hold views diametrically opposed to their own; this is particularly the case for left-leaning organisations in the UK, which have established ties with far-right movements in Russia. ñ In an era when marginal individuals and parties in the UK are looking for greater influence and exposure, Russia makes for a frequent point of ideological convergence, and Putin makes for a deceptive and dangerous friend. -

Yes Beyond Salmond

SSV Forum 2_leaflet 22/02/2014 01:29 Page 1 YWHYE SUSPPO RTBINGE INDYEPEONDENNCED DOE SSN’T AMAKLE YMOU A NOATINONADLIST Following the success oF our the polls show far more support for first Voice Forum in December examining independence among working class the scottish government’s white Paper, scots than the wealthy. this event aims ‘scotland’s Future’, the scottish socialist to open up discussion that is both Voice – scotland’s only socialist stimulating and informative and helps newspaper, edited, published and printed shape the direction of the independence here in scotland – again brings together movement in the months ahead. leading figures on the pro-independence left to discuss another important aspect the Forum takes place on saturday 8 of our campaign for self-determination. march from 10am-2pm in the martin hall, new college, edinburgh university, this, our second Forum discussion, the mound, edinburgh. refreshments features a panel of speakers reflecting will be provided. the wide spectrum of pro-independence progressive opinion: tickets for the event are free but space • Jim sillars Former labour mP and is limited so reservations are again Former Deputy leader of the snP, author strongly recommended. tickets can be of ‘in Place of Fear ii – a socialist obtained in advance via the ssP Programme For independence’ website scottishsocialistparty.org or by • Jean urquhart independent msP for emailing [email protected] the highland and islands To order your copy of • allan grogan chair of ‘labour For ‘The Case For An independence’ Independent Socialist • cllr maggie chaPman scottish Scotland’ by Colin Fox, send green Party co-convener £5 to: SSP, Suite 370, • Jonathon shaFi radical 4th Floor, Central Chambers, independence campaign 93 Hope St, Glasgow G2 6LD. -

Spice Briefing

LIST OF ALL MSPS A-Z: SESSION 2 Scottish Parliament The Fact sheet provides an alphabetical list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the second Fact sheet parliamentary session, 7 May 2003 – 2 April 2007. It also lists the party for which each MSP was elected as well as the constituency or region that they represented. MSPs: Historical The abbreviation (C) has been used to indicate a constituency seat Series and (R) to indicate a regional seat. 12 March 2009 1 MSP Party Constituency or Region Brian Adam Scottish National Party Aberdeen North (C) Bill Aitken Conservative Glasgow (R) Wendy Alexander Labour Paisley North (C) Andrew Arbuckle1 Liberal Democrat Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Jackie Baillie Labour Dumbarton (C) Shiona Baird Green North East Scotland (R) Richard Baker Labour North East Scotland (R) Chris Ballance Green South of Scotland (R) Mark Ballard Green Lothians (R) Scott Barrie Labour Dunfermline West (C) Sarah Boyack Labour Edinburgh Central (C) Rhona Brankin Labour Midlothian (C) Ted Brocklebank Conservative Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Robert Brown Liberal Democrat Glasgow (R) Derek Brownlee2 Conservative South of Scotland (R) Bill Butler Labour Glasgow Anniesland (C) Rosemary Byrne3 Scottish Socialist Party South of Scotland (R) Dennis Canavan Independent Falkirk West (C) Malcolm Chisholm Labour Edinburgh North and Leith (C) Cathie Craigie Labour Cumbernauld and Kilsyth (C) Bruce Crawford Scottish National Party Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Roseanna Cunningham Scottish National Party Perth (C) Frances Curran Scottish Socialist Party West of Scotland (R) Margaret Curran Labour Glasgow Baillieston (C) David Davidson Conservative North East Scotland (R) Susan Deacon Labour Edinburgh East and Mussleburgh (C) James Douglas-Hamilton Conservative Lothians (R) Helen Eadie Labour Dunfermline East (C) Fergus Ewing Scottish National Party Inverness East, Nairn and Lochaber (C) 1 Andrew Arbuckle became the regional member for Mid Scotland and Fife on 10 January 2005. -

Urgent Appeal for Solidarity

Urgent Appeal for Solidarity https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article855 Scottish Socialist Party Urgent Appeal for Solidarity - News from around the world - Publication date: Friday 12 August 2005 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/3 Urgent Appeal for Solidarity The Scottish Socialist Party is under attack. Four SSP Members of Parliament and their staff have been issued with a month long ban without wages for defending the right to protest against the meeting of the G8 leaders. We are attempting to generate as much international opposition as possible to this draconian attack. Therefore we request your solidarity in the following ways: circulate this letter among your own members, affiliates and contacts. Sign the online petition at: http://www.thepetitionsite.com/takeaction/754099600?ltl=1122382283 Write to George Reid, Presiding Officer of the Scottish Parliament, to register your support for the SSP: Presiding Officer, Queensberry House, the Scottish Parliament, Holyrood, Edinburgh EH99 1SP Email: [email protected] Contribute to the SSP's fighting fund, to pay the cost of legal action to overturn the suspension of our representatives, and to cover the wages of our staff: Scottish Socialist Party, 70 Stanley Street, Glasgow, G41 1JB, Scotland Tel: +44 870 752 2505 email: [email protected] On the 30 June 2005 four Scottish Socialist Party parliamentary representatives were summarily suspended and stripped of their pay and parliamentary allowances for the month of September. The financial suspensions will also mean 28 members of staff, not involved in the protest, will also not be paid. -

Hugo Gorringe and Michael Rosie University of Edinburgh

'Pants to Poverty'? Making Poverty History, Edinburgh 2005 provided by Research Papers in Economics View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by by Hugo Gorringe and Michael Rosie University of Edinburgh Sociological Research Online, Volume 11, Issue 1, < http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/1/gorringe.html> doi:10.5153/sro.1261 Received: 4 Oct 2005 Accepted: 16 Mar 2006 Published: 31 Mar 2006 Abstract July 2005 saw 225,000 people march through Edinburgh in the city's largest ever demonstration. Their cause was the idealistic injunction to 'Make Poverty History' (MPH). This paper presents an analysis of the MPH march, focusing particularly on the interplay between protestors, the police and the media. Drawing on ongoing research, it interrogates the disjunction between projected and actual outcomes, paying particular scrutiny to media speculation about possible violence. It also asks how MPH differed from previous G8 protests and what occurred on the day itself. The paper considers three key aspects: the composition and objectives of the marchers (who was on the march, why they were there and what they did?), the constituency that the protestors were trying to reach, and the media coverage accorded to the campaign. The intent underlying this threefold focus is an attempt to understand the protestors and what motivated them, but also to raise the question of how 'successful' they were in communicating their message. Keywords: Make Poverty History, Protest, Media, Policing, Social Movements Introduction 1.1 In July 2005 225,000 people marched through Edinburgh to ‘make poverty history’. They aimed to pressure the Group of Eight (G8) leaders to act on debt, trade, climate change and Africa. -

The Pro-Independence Radical Left in Scotland Since 2012 Nathalie DUCLOS Université De Toulouse 2-Jean Jaurès

The Pro-independence Radical Left in Scotland since 2012 Nathalie DUCLOS Université de Toulouse 2-Jean Jaurès The Pro-independence Radical Left in Scotland since 2012 Nathalie DUCLOS Université de Toulouse 2-Jean Jaurès CAS EA 801 [email protected] Résumé Cet article a pour objectif de dessiner les contours de la gauche radicale et indépendantiste dans l’Écosse d’aujourd’hui. La longue campagne qui a précédé le référendum sur l’indépendance écossaise de 2014 (celle-ci ayant commencé dès 2012, soit plus de deux ans avant le référendum lui-même) a donné naissance à un nouveau paysage politique, surtout à gauche. Celui-ci se caractérise par deux tendances : la multiplication de nouvelles organisations (par exemple la Radical Independence Campaign, Common Weal et le Scottish Left Project), souvent (mais pas toujours) favorables à l’indépendance écossaise, et le renforcement des partis indépendantistes de gauche ou de centre-gauche déjà existants, qui ont tous gagné énormément de nouveaux adhérents. Cet article se concentre sur les organisations indépendantistes de la gauche radicale en Écosse : celles créées depuis 2012, ainsi que celles qui leur ont donné naissance. Après avoir présenté chacune de ces organisations et les liens qui existent entre elles, il se penche sur leurs stratégies à court terme (présenter des candidats et remporter des sièges aux élections parlementaires écossaises de 2016) et à moyen ou long terme (faire campagne pour l’organisation d’un nouveau référendum sur l’indépendance écossaise et proposer une vision de l’indépendance différente de celle mise en avant par le Scottish National Party). Abstract This article aims at mapping the pro-independence radical left in today’s Scotland. -

Ssv 483 Ssv-483

Katie Bonnar: attainment gap Colin Fox: it’s time to won’t close without determined make the socialist anti-poverty action case for independence • see page 9 • see page 10 £1 • issue 483 • 9th – 22nd September 2016 scottishsocialistvoice.wordpress.com Scotland’s ‘National Conversation’: WE NEED TO PHOTO: Craig Maclean POVERTY HOUSING TeAnd loLw pKay an d ABObuilUd 150T ,000 ... zero hours – £10/hr affordable social minimum wage homes to rent for all, NOW PRIVATE PROFIT nationalise railways, energy, GREEN ENERGY and essential harness our services resources for TRIDENT people and planet scrap nuclear subs – not profit WELFARE stop benefit – no to NATO sanction harassment – sack ATOS & CAPITA ScottishSocialistVoice.wordpress.com /ScottishSocialistVoice @ssv_voice WELFARE The Scottish Government’s welfare ‘conversation’ needs to be two-way by Sandra Webster DON’T PASS ON TORY AUSTERITY: the SNP should protect folk from Tory policies, which we know will only worsen LAST WEEK the SNP called (PHOTO: Simon Whittle) for a conversation with Scot - land. For those of us who called for such a debate during the ref - erendum this is nothing new. The SNP conversation is noth - ing but a number of questions where you can respond yes or no. Quite one sided. However after The Smith Commission, difficult powers have been given to the Scottish Government. Time to look at how the Scottish Government should use these for the better good and for us on the left to have a two way conversation. care for them, the dreaded doctors rather than the assess - this policy where being a few The Smith Commission gave ATOS and CAPITA assessments ment of professionals who have minutes late, or having to miss an difficult benefit decisions to cause so much fear. -

Mise En Page 1

pRimaiRe de la gaUche eN fRaNce. l’heURe de la deRNièRe vallS a SoNNé poUR le pS PAGE 5 JAA / PP / JOURNAL, 1281 GENÈVE 13 SUCCESSEUR DE LA «VOIX OUVRIÈRE» FONDÉE EN 1944 • WWW.GAUCHEBDO.CH N° 4 • 27 JANVIER 2017 • CHF 3.- costa-gavras était l’invité Rie iii: l’économiste en chef colin fox plaide pour une d’honneur du festival du film de l’USS daniel lampart ecosse socialiste et grec de Berlin. interview page 8 contre-attaque page 2 indépendante page 6 Regarder la presse mourir à petit feu IL FAUT LE DIRE... MÉDIAS • La presse romande souffre, mais la question d’une aide publique directe demeure un tabou en Suisse et les éditeurs ne semblent pas disposés à investir dans la mission trop peu rentable du service à la démocratie. Une gauche qui oins de 2 ans après avoir réuni au sein d’une sait où elle va même «Newsroom» différents titres, parmi M Les prestations de l’aide sociale du can- lesquels Le Temps, et l’Hebdo, Ringier Axel Springer (RAS) annonçait lundi la cessation de paru- ton de Neuchâtel sont revues à la baisse. tion de l’Hebdo, invoquant «le recul incessant des La principale mesure de restriction recettes publicitaires et des ventes et un contexte concerne les jeunes adultes (18-35 ans) économique aux perspectives défavorables». La sans activité, qui verront leur forfait mesure devrait toucher 37 personnes, précise le d’entretien, soit le montant destiné à communiqué, soit bien plus que le nombre de jour- s’acquitter de toutes les dépenses hors nalistes employés par l’Hebdo, qui se monte à 15. -

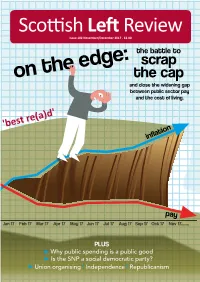

Scottish Leftreview

ScottishLeft Review Issue 102 November/December 2017 - £2.00 'best re(a)d' ASLEF CALLS FOR AN INTEGRATED, PUBLICLY OWNED, ACCOUNTABLE RAILWAY FOR SCOTLAND (which used to be the SNP’s position – before they became the government!) Mick Whelan Tosh McDonald Kevin Lindsay General Secretary President Scottish Ocer ASLEF the train drivers union- www.aslef.org.uk Trade Union Recognition agreements on all construction sites Adherence to collective agreements Direct employment No blacklisting No public contracts for blacklisters No Bogus self employment or umbrella schemes Protect skills Proper apprenticeships The Rank & File was born out of an attack on the skills of electricians in 2011 by eight of the major mechanical and electrical construction companies in the UK. We have also been in the Health & Safety forefront in the fight against blacklisting with our partners, the Blacklist Support Group. We seek the adherence of collective agreements on all construction sites and recognition of all elected shop stewards and safety reps. The Rank & File, who is made up mostly of Unite members but Contact: also count members of GMB and Ucatt among our ranks, are determined to change the face of construction for the benefit of working people by transforming the attitudes of companies in the Email: [email protected] industry to realise the benefits of having an organised workforce. To do this we need the assistance of clients such as the Scottish government, local authorities, NHS and Scotland’s Universities and Colleges through their procurement processes, in line with the Scottish Unite Scottish Rank and File government’s Fair Work Framework. -

Standing up for Scotland's Working Class Majority

s 2015 General Election manifesto FOR AN INDEPENDENT SOCIALIST SCOTLAND: STANDING UP FOR SCOTLAND’S WORKING CLASS MAJORITY 201 5 General Election manifesto FOR AN INDEPENDENT SOCIALIST SCOTLAND: STANDING UP F OR SC OTLAN D’S WORKI NG CL ASS M AJORITY CONTEN TS Introduction 5 Independence deferred 7 More powers for Holyrood 7 Standing up for Scotland’s working class majority 8 How is this programme to be paid for? 21 Building Scotland’s Socialist Party 21 ISBN 978-0-9571986-7-8 Design and layout by @revolbiscuit Promoted by Colin Fox, 81/5 Clerk Street, Edinburgh EH8 9JG. Printed by Events Armoury, 9 West Richmond Street, Edinburgh EH8 9EF www.ScottishSocialistParty.org INTRODUCTION ransom will continue to call the shots through the politicians they keep in their pockets. The outcome of this General Election hangs in In stark contrast to the inconclusive outcome the balance. Labour and the Tories are running expected at Westminster however May’s neck and neck in the polls. Neither has General Election in Scotland, the first test of sufficient support to form a government. public opinion since the independence Neither enjoys the confidence of a majority of referendum, looks set to produce a dramatic voters. Each may try to govern as a minority or reversal for Labour. They currently hold most more likely form a coalition with the much- Scottish seats. But the polls suggest Labour reduced and much-despised Lib Dems. could lose two thirds of them as its chronic David Cameron’s plea to be given a second political decline, a process the Scottish term rests on the premise that the Tories have Socialist Party first identified 16 years ago, steered Britain out of a recession and out of the reaches a dramatic climax. -

“I'm Not a Nationalist But…”

“I’m not a nationalist but…” On mobilisation and identity formation of the Scottish independence movement Signe Askersjö SAM212 Master’s thesis Department of Social Anthropology, Stockholm University 30 ECTS credits, Spring 2018 Supervisor: Johanna Gullberg 2 3 Abstract This study examines the mobilisation and identity formation of the Scottish independence movement post-referendum. By analysing arguments, emotions and actions in support for independence, I aim to discuss how the movement make use of cultural perspectives on history for continuous mobilisation. The study focuses on the members of the umbrella organisation of Yes Scotland, which is a diverse network of activist and party-political groups. To understand the movement, I have made use of a political and active approach such as participating in meetings and at demonstrations. Importantly, while I acknowledge how the Scottish independence movement navigates within a discourse of nationalism because of its nationalist character, I argue that the movement mainly make use of an alternative ideology. This ideology is tied to historical narratives which are remade in present forms and take several expressions. For instance, I claim that this ideology generates the practice of international solidarity as well as a specific identity which is constructed and reproduced for one specific political project: to achieve Scottish independence. This thesis is a contribution to the study of social movements, as well as it provides understanding of reasoning beyond and within nationalism. Keywords: Scottish independence movement, social movements, nationalism, identity, historicity and solidarity. 4 Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to all the interlocutors for their time, participation and engagement, I am most grateful.