Interrogating Shariah Practice in Yoruba Land, 1820-1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

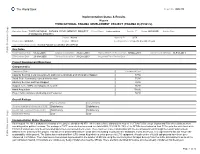

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

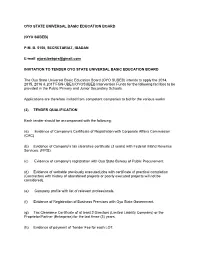

OYO STATE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION BOARD (OYO SUBEB) P.M. B. 5150, SECRETARIAT, IBADAN E-Mail: [email protected] INVITATION

OYO STATE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION BOARD (OYO SUBEB) P.M. B. 5150, SECRETARIAT, IBADAN E-mail: [email protected] INVITATION TO TENDER OYO STATE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION BOARD The Oyo State Universal Basic Education Board (OYO SUBEB) intends to apply the 2014, 2015, 2016 & 2017 FGN-UBEC/OYOSUBEB Intervention Funds for the following facilities to be provided in the Public Primary and Junior Secondary Schools. Applications are therefore invited from competent companies to bid for the various works. (2) TENDER QUALIFICATION Each tender should be accompanied with the following: (a) Evidence of Company’s Certificate of Registration with Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) (b) Evidence of Company’s tax clearance certificate (3 years) with Federal Inland Revenue Services. (FIRS). (c) Evidence of company’s registration with Oyo State Bureau of Public Procurement (d) Evidence of veritable previously executed jobs with certificate of practical completion (Contractors with history of abandoned projects or poorly executed projects will not be considered). (e) Company profile with list of relevant professionals. (f) Evidence of Registration of Business Premises with Oyo State Government. (g) Tax Clearance Certificate of at least 2 Directors (Limited Liability Company) or the Proprietor/Partner (Enterprise) for the last three (3) years. (h) Evidence of payment of Tender Fee for each LOT. (i) A sworn affidavit in line with the provision of part IV, section22 (6a, b, c, e & f) of the Oyo State Public Procurement Law 2010 stating that none of the persons connected with the bid process in the procuring entity or bureau has any pecuniary interest and that the company is not in receivership of any form of insolvency, bankrupt nor debarment and that the company nor any of the directors) of the company has been convicted of financial crimes. -

Water in Yoruba Belief and Imperative for Environmental Sustainability

Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religion www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8443 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.28, 2017 Water in Yoruba Belief and Imperative for Environmental Sustainability Adewale O. Owoseni Department of Philosophy, University of Ibadan, University of Ibadan Post Office, Nigeria Abstract The observation by scholars that the typical African people are often overtly religious in matters of interpreting reality demands a critical outlook with allusion to apt consideration of phenomena in relevant locale within the African space. The phenomenon of water has received copious attention worldwide and the need to consider this within an African nay Yoruba worldview is timely. The Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria are wont to express that ‘water is the converge of good health, no one can despise it’ – omi labuwe, omi labumi, eni kan kii ba omi s’oota . This expression among other narratives convey a symbolic and paradoxical representation of water, which depicts the metaphysical dialectics of water in Yoruba belief. Basically, it renders the phenomenon of water as an entity that has the potency to vitalize and disrupt life-forms, given the beliefs regarding its place in relationship with certain animals like buffalo, fish and some endangered species, plants, trees as well as humans. Resultant impediments that fraught environmental order such as flood, draught and water borne diseases or outbreak in this regard are often linked to these beliefs. This is believed to be due to negating demands of the essential place of water by aberrant practices/acts, abuse, negligence of venerating ancestral grooves, goddesses or spirit. In lieu of this, this discourse adopts a hermeneutic analysis of the phenomenon and argues that the understanding of water in indigenous Yoruba belief is underscored by the dialectics of positive and negative causes that also impact the course of environmental sustainability. -

The Osun Drainage Basin in the Western Lithoral Hydrological Zone of Nigeria: a Morphometric Study

GEOGRAFIA OnlineTM Malaysian Journal of Society and Space 12 issue 8 (71 - 88) 71 © 2016, ISSN 2180-2491 The Osun Drainage Basin in the Western Lithoral Hydrological Zone of Nigeria: A morphometric study Ashaolu Eniola Damilola1 1Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ilorin, PMB 1515, Ilorin, Nigeria Correspondence: Ashaolu Eniola Damilola (email: [email protected]) Abstract The importance of drainage basin as a planning unit for water resources development and management cannot be overemphasized and this requires accurate characterization of the drainage basin. This study takes a closer look at the Osun drainage basin with a view to updating the existing records, estimate the morphometric features and make hydrological inferences. The data used in this study include a 30m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) acquired from the United State Geological Survey (USGS), geology map of Nigeria acquired from Nigeria Geological Survey Agency (NGSA), Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) prepared by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), and the 1991 locality population data of Nigeria acquired from National Population Commission (NPC). Remote sensing and GIS techniques were adopted in the analysis of the data using ArcGIS 10.2. The acquired DEM was used to delineate Osun drainage basin and 21 morphometric parameters were estimated. The results revealed that Osun drainage basin is a 4th order drainage basin, with an area of 9926.22km 2 , and a length of 213.08km. The area covered by the two geology types and the four soil types were quantified and it revealed that 93.28% of the basin is underlain by the Basement Complex rocks, while 50.89% of the basin is covered by sandy clay loam soil. -

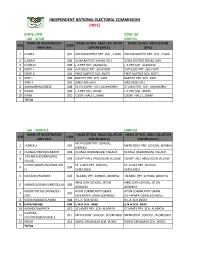

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM. -

Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria

Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria. May, 2015 i Table of Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................................v Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements ...............................................................................................................................................vii Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................viii 1.0 Background ............................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Objectives of the Mapping Project ..................................................................................................2 1.3 Justification for the Survey ..................................................................................................................2 2.0. Mapping Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 -

Assessment of Silk Yarn Production in Ondo and Oyo

ASSESSMENT OF SILK YARN PRODUCTION IN ONDO AND OYO STATES, NIGERIA. BY ODILI, NNEKA ZELDA B.TECH INDUSTRIAL DESIGN (TEXTILES) IDD/99/2425 A THESIS IN THE DEPARMENT OF INDUSTRIAL DESIGN SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULIFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF TECHNOLOGY IN INDUSTRIAL DESIGN OF THE FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE NIGERIA. JULY, 2012. ABSTRACT Sericulture, the technique of silk yarn production, is an agro- industry, which has contributed to the urban and rural economy of Ondo and Oyo States of Nigeria. Silk yarn is a protein produced from silk-glands of silkworms. The value attached to silk yarn clothing cannot be over emphasized because the production of silk yarn as a natural protein fibre which has been used for fabric production for centuries even before the coming of the white men in Nigeria. This study was able to assess silk yarn production in Ondo and Oyo States of Nigeria. The towns selected were Owo, Akure and Ondo in Ondo States and Iseyin and Oyo in Oyo State. To achieve this, data on issues relating to the specific objectives of the study were collected through structured questionnaires. Four sets of structured questionnaires were administered to the producers, weavers, traders and consumers of silk yarn production in four randomly selected towns in Ondo and Oyo state Nigeria .Viz (Owo, Ondo, Akure, Iseyin and Oyo). The questionnaires were designed to obtain information on age groups, occupation and sex of those interested in silk yarn production. The questionnaires were collected, collated and analyzed. -

List of Community Banks Converted to Microfinance Banks As at 31St

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA IMPORTANT NOTICE LIST OF COMMUNITY BANKS THAT HAVE SUCESSFULLY CONVERTED TO MICROFINANCE BANKS AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2007 Following the expiration of December 31, 2007 deadline for all existing community banks to re-capitalize to a minimum of N20 million shareholders’ fund, unimpaired by losses, and consequently convert to microfinance banks (MFB), it is imperative to publish the outcome of the conversion exercise for the guidance of the general public. Accordingly, the attached list represents 607 erstwhile community banks that have successfully converted to microfinance banks with either final licence or provisional approval. This list does not, however, include new investors that have been granted Final Licences or Approvals-In- Principle to operate as microfinance banks since the launch of Microfinance Policy on December 15, 2005. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) hereby states categorically that only the community banks on this list that have successfully converted to microfinance banks shall continue to be supervised by the CBN. Members of the public are hereby advised not to transact business with any community bank which is not on the list of these successfully converted microfinance banks. Any member of the public, who transacts business with any community bank that failed to convert to MFB does so at his/her own risk. Members of the public are also to note that the operating licences of community banks that failed to re-capitalize and consequently do not appear on this list, have automatically been revoked pursuant to Section 12 of BOFIA, 1991 (as amended). For the avoidance of the doubt, new applications either as a Unit or State Microfinance Banks from potential investors or promoters shall continue to be received and processed for licensing by the Central Bank of Nigeria. -

FACTORS ASSOCIATED with GROUP COHESION AMONG BEEKEEPERS in OYO STATE, NIGERIA Omotesho, K

Nigerian Journal of Rural Sociology Vol. 17, No. 2, 2017 FACTORS ASSOCIATED WIT. GROU2 CO.ESION AMONG EEKEE2ERS IN OYO STATE, NIGERIA Omotesho, K. F., Adesiji, -. 4., Akinrinde, A. F., and Adabale, T. O. .epartment of Agricultural E0tension and Rural .evelopment, niversity of 2lorin, 2lorin, Nigeria Correspondence contact detailsA kfomoteshoJgmail.com; omotesho.kfJunilorin.edu.ng; 08034739568 A STRACT The success of the participatory approach to e0tension in Nigeria is threatened by poor willingness among farmers to sustain active membership of groups particularly in the absence of ongoing developmental projects on which to converge. The objectives of the study were to identify beekeepers> reasons for association membership; ascertain the level of satisfaction of members; assess the level of group cohesion, andidentify the constraints to cohesion. A two1stage random sampling techniDue was used to select 151 respondents across beekeepers> associations in the state. .ata were obtained through a structured Duestionnaire. .escriptive statistics and the Pearson>s Product 5oment Correlation were used to analyse data collected. The results revealed that all the beekeepers> associations were not limited by si6e, membership was open, and the average membership si6e was 31. Opportunity to share information was the most important reason why beekeepers joined the associations (5ean ScoreN3.46,. The study concluded that though membership satisfaction was low (5ean score N2.59,, the level of cohesion was fair (5eans ScoreN3.61,. 5embers> satisfaction, mode of group formation and age of the associations significantly influenced group cohesion at p]0.01. The study recommended that the moderate level of cohesion could be improved through training of members on group dynamics. -

Sep 21-30, 2014

NIGERIAN METEOROLOGICAL AGENCY NATIONAL WEATHER FORECASTING AND CLIMATE RESEARCH CENTRE, BILL CLINTON DRIVE, NNAMDI AZIKIWE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, P.M.B. 615, GARKI, ABUJA, NIGERIA Agrometeorological Bulletin No.27, Dekad 3, September (21 –30) 2014 ISSN: 2315-9790 SUMMARY The Inter Tropical Discontinuity (ITD)'s position fluctuates between Latitudes 14 and 15oN. Generally, there was a reduction in rainfall activity particularly in the northern parts of the country. The highest rainfall amount was recorded over Abeokuta with 209.5mm in 7 rain-days, followed by Ikeja and Ijebu-Ode with 189.3mm in 7 rain- days and 185.3mm in 9 rain-day respectively. The country continued to experience normal maximum temperatures with the highest value of 34.60C recorded over Nguru and Jos having the lowest value of 25.80C. The major agricultural activities in the country included: Harvest of, cereals, yams, cassava, sweet potatoes, groundnut, and fresh vegetables. As we approach the end of the raining season in the North, preparation of nurseries, transplanting and other dry season activities are the major activities in these areas. 1.0 RAINFALL PATTERN 1.1 Rainfall Anomaly (Deficit / Surplus) above and generally reveals a good rainfall distribution. However, stations in the extreme North recorded less 14 rainfall signalling an approach to cessation of the rains. SOK KAT NGU The highest rainfall amount was recorded over GUS KAN 12 POT MAI Abeokuta with 209.5mm in 7 rain-days, followed by YEL ZAR KAD BAU GOM Ikeja and Ijebu-Ode with 189.3mm in 7 rain-days and 10 BID MIN JOS 185.3mm in 9 rain-day respectively. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Developing Appropriate Techniques to Alleviate the Ogun River Network Annual Flooding Problems S.O.OYEGOKE, A.O

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Landmark University Repository International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 3, Issue 2, February -2012 1 ISSN 2229-5518 Developing Appropriate Techniques to Alleviate the Ogun River Network Annual Flooding Problems S.O.OYEGOKE, A.O. SOJOBI Abstract - The perennial annual flooding problems occurring in Lagos and Ogun States during the rainy season due largely to release of excess water from the multi-purpose Oyan Dam reservoir built across Oyan River, a tributary of Ogun River, located in Abeokuta North Local Government of Ogun State, has reached unacceptable level. Annually, the flooding hazard causes severe economic, social, ecological and environmental impacts such as displacement of no less than 1,280 residents, interruption of major roads which inevitably leads to loss of valuable man-hours, infection of surface and ground water leading to increased incidences of water-borne diseases, disruption of commercial and educational activities and recession of shoreline. This paper reviews the genesis and root causes of the flooding problems with a view to proffer the best approach to alleviate and solve this problem on a permanent basis combining hydraulic and hydrological best practices. Keywords: flood, dam, reservoir, management, hydraulic, hydrology. —————————— —————————— 1.0 INTRODUCTION of 65 days produced an estimated loss of US$54.6Million.Meanwhile, for about fifty (50) years from Worldwide, dams have contributed significantly to socio- 1930 to 1982, only a low to medium floods occurred (Tucci, economic development of countless developed and 1994). Integration of flood forecasting model with a lead developing nations.