Some Aspects of Yoruba Urbanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Microfinance and Economic Activities of Rural Dwellers in Kwara South Senatorial District of Nigeria

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 15; August 2011 INFORMAL MICROFINANCE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES OF RURAL DWELLERS IN KWARA SOUTH SENATORIAL DISTRICT OF NIGERIA IJAIYA, Muftau Adeniyi Department of Accounting and Finance University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria E-mail : [email protected], Phone: +2348036973561 Abstract Rural areas, like urban areas have increasing demand for credit because such credit reduces the impact of seasonality on incomes. However, formal financial institutions have maintained low presence in the rural areas. This has affected the rural dwellers’ access to deposit savings and credits that can improve their economic activities. This study examined the influence of informal microfinance on economic activities of rural dwellers in the selected rural areas of Kwara South Senatorial District. Using a multiple regression analysis, six hundred (600) questionnaire was administered on members of informal microfinance institution in the study area, the study found that fund provided as credit facilities for transaction purposes, funds for housing and combating diseases have significant influence on the economic activities of the rural areas. The study recommends group savings and group lending in order to increase savings and credits to the rural dwellers. Government should also provide improved infrastructural facilities that would enable rural dwellers have more access to their economic activities Key Words: Microfinance, Informal, Economic Activities, Rural, Kwara 1.0 Introduction Africa‟s development challenges go deeper than low income, falling trade shares, low savings and slow growth. They also include inequality and uneven access to productive resources, social exclusion and insecurity especially among the women (Pitamber, 2003). However, more specific concern is raised in Nigeria due to rural-urban disparities in income distribution, access to education and health care services, and prevalence of ethnic or cross-boundary conflicts. -

Geotechnical Investigation of Road Failure Along Ilorin-Ajase – Ipo Road Kwara State, Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Environment and Earth Science www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online) Vol. 3, No.7, 2013 Geotechnical Investigation of Road Failure along Ilorin-Ajase – Ipo Road Kwara State, Nigeria. Dr. I.P. Ifabiyi [email protected] Department of Geography and Environmental Management Faculty of Business and Social Science P.M.B 1515, University Of Ilorin, Ilorin. Kwara State, Nigeria. Mr. Kekere, A.A [email protected] Department of Art and Social Science, Unilorin Secondary School, University Of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. Abstract The incessant failure of road network in Nigeria has generated a lot of concern by road users and government. Apart from lives and properties that are lost annually to road crashes, road rehabilitation across the country has become a financial burden to the federal government. Several factors have been identified to be responsible to road failure in Nigeria; they include geological, geomorphological, road usage, bad construction and wrong approach to maintenance. Hence, this paper examines some of the factors responsible for road failure along Ilorin-Ajase Ipo road, Kwara State Nigeria. Soil samples were collected from Five (5) portions of the road that are badly affected by road failure. These portions include: Agricultural and Rural Management Training Institute (ARMTI) 17+800km, Kabba Owode 18+00Km, Idofian 23+700Km, Koko 29+700Km and Omupo 35+700Km axis. The soil samples collected were analyzed four engineering properties: particle size distribution (PSD),atterberg limit, compaction test California Bearing Ratio (CBR). -

05 Onyango-Ouma

HEALTH POLICY AND PLANNING; 16(Suppl. 1): 24–32 © Oxford University Press 2001 An evaluation of Health Workers for Change in seven settings: a useful management and health system development tool WASHINGTON ONYANGO-OUMA,1 ROSE LAISSER,2 MUSIBA MBILIMA,3 MARGARET ARAOYE,4 PATRICIA PITTMAN,5 IRENE AGYEPONG,6 MAIRO ZAKARI,7 SHARON FONN,8 MARCEL TANNER9 AND CAROL VLASSOFF10 1KEDAHR Project, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Ministry of Health, Kisumu, Kenya, 2Institute of Allied Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 3University Health Centre, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 4Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Ilorin, Nigeria, 5Women, Health and Development Program, Division of Health and Human Development, Pan American Health Organization, Washington, DC, 6Ministry of Health, Dangme West Health Research Centre, Dodowa, Ghana, 7Entomology and Parasitology Division, National Institute for Trypanosomiasis Research, Kadua, Nigeria, 8Women’s Health Project, Department of Community Health. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 9Swiss Tropical Institute, Basel, Switzerland and 10Canadian International Development Agency, Hull, Quebec, Canada This paper presents the findings of a multi-centre study assessing the impact of Health Workers for Change (HWFC) workshops in seven different primary care sites, based on the common core protocol described in this paper. The paper discusses a common methodology used by the studies, consisting of a triangulation of qualitative and quantitative methods. Such methodologies are inherently complex as they require com- parisons across systems, sites and procedures. The studies were conducted in six sites in Africa and one site in Argentina. Generally, the intervention resulted either in positive change or in no change, except in the area of staff relationships where conflicts were more frequent after the intervention than before. -

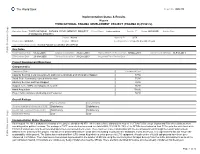

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Introduction Urban Reproductive Health

Family Planning Effort Index Ibadan, Ilorin, Abuja, and Kaduna FPE Nigeria 2011 Introduction Nigeria has a current population of 152 million with a growth rate of 3.2%, a Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) of 15.4 and a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 5.7. Nigeria plays an important role in the socio- political context of West Africa, since it constitutes 50.2% of the total population of the region (PRB 2009, DHS 2008). In response to the pattern of high growth rates, the National Policy on Population for Sustainable Development was launched in 2005. The policy recognized that population factors, social and economic development, and environmental issues are irrevocably interconnected and addressing them are critical to the achievement of sustainable development in Nigeria. The Nigerian population policy sets specific targets aimed at addressing high rates of population growth including a reduction in the annual national growth rate to 2% or lower by 2015, a reduction in the TFR of at least 0.6 children per woman every five years, and an increase in CPR of at least 2% points per year. However, Nigeria still has a 20% unmet need for family planning (NPC and ICF Macro, 2009). Family Planning was included in the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) as an indicator for tracking progress of improving maternal health. This concept of integrating family planning with maternal health services is the same approach that the Nigerian Ministry of Health is utilizing with messages related to family planning highlighting the links between utilization and reduced maternal mortality. However, continuing low levels of CPR and high levels of maternal mortality highlight the importance of an increased emphasis on family planning both within the context of maternal health and other health and social benefits. -

From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940

The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History ISSN: 0308-6534 (Print) 1743-9329 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fich20 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly To cite this article: Samuel Fury Childs Daly (2019) From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 47:3, 474-489, DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 Published online: 15 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fich20 THE JOURNAL OF IMPERIAL AND COMMONWEALTH HISTORY 2019, VOL. 47, NO. 3, 474–489 https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Indirect rule figured prominently in Nigeria’s colonial Nigeria; Abeokuta; crime; administration, but historians understand more about the police; indirect rule abstract tenets of this administrative strategy than they do about its everyday implementation. This article investigates the early history of the Native Authority Police Force in the town of Abeokuta in order to trace a larger move towards coercive forms of administration in the early twentieth century. In this period the police in Abeokuta developed from a primarily civil force tasked with managing crime in the rapidly growing town, into a political implement of the colonial government. -

Factors Affecting Effective Teaching and Learning of Economics in Some Ogbomosho High Schools, Oyo State, Nigeria

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.7, No.28, 2016 Factors Affecting Effective Teaching and Learning of Economics in Some Ogbomosho High Schools, Oyo State, Nigeria Gbemisola Motunrayo Ojo Vusy Nkoyane Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, College of Education, University of South Africa 0001 Abstract This study was carried out to examine the present curriculum of Economics as a subject in some Ogbomoso Senior High Schools and to determine factors affecting effective teaching of economics in the schools. Variables such as number of students, teachers’ ratio available textbooks were also examined. The study adopted descriptive design since it is an ex post facto research. The target population for this study is Ogbomosho North Local Government Area of Oyo State comprising nine (9) High Secondary Schools. Three (3) teachers of economics and five (5) students from each school were used in answering the questionnaires. The study revealed high number of economics students (5,864) as against 26 teachers in nine (9) public schools under study. This gives a very high teacher-student ratio of 1:225. The findings also showed that there one lack of teaching aids, library facilities and where available, there is lack of textbooks of Economics. All the schools studied were highly dense resulted into high students’ population. Based on the findings of his study, the federal and the state governments should employ more teachers, especially in Economics to checkmate rising teacher student ratio. More senior secondary schools should be built with the increasing student population within the LGA under study. -

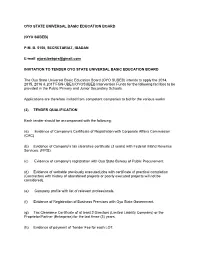

OYO STATE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION BOARD (OYO SUBEB) P.M. B. 5150, SECRETARIAT, IBADAN E-Mail: [email protected] INVITATION

OYO STATE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION BOARD (OYO SUBEB) P.M. B. 5150, SECRETARIAT, IBADAN E-mail: [email protected] INVITATION TO TENDER OYO STATE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION BOARD The Oyo State Universal Basic Education Board (OYO SUBEB) intends to apply the 2014, 2015, 2016 & 2017 FGN-UBEC/OYOSUBEB Intervention Funds for the following facilities to be provided in the Public Primary and Junior Secondary Schools. Applications are therefore invited from competent companies to bid for the various works. (2) TENDER QUALIFICATION Each tender should be accompanied with the following: (a) Evidence of Company’s Certificate of Registration with Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) (b) Evidence of Company’s tax clearance certificate (3 years) with Federal Inland Revenue Services. (FIRS). (c) Evidence of company’s registration with Oyo State Bureau of Public Procurement (d) Evidence of veritable previously executed jobs with certificate of practical completion (Contractors with history of abandoned projects or poorly executed projects will not be considered). (e) Company profile with list of relevant professionals. (f) Evidence of Registration of Business Premises with Oyo State Government. (g) Tax Clearance Certificate of at least 2 Directors (Limited Liability Company) or the Proprietor/Partner (Enterprise) for the last three (3) years. (h) Evidence of payment of Tender Fee for each LOT. (i) A sworn affidavit in line with the provision of part IV, section22 (6a, b, c, e & f) of the Oyo State Public Procurement Law 2010 stating that none of the persons connected with the bid process in the procuring entity or bureau has any pecuniary interest and that the company is not in receivership of any form of insolvency, bankrupt nor debarment and that the company nor any of the directors) of the company has been convicted of financial crimes. -

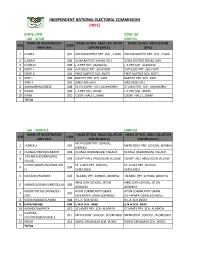

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM. -

(IITA) Oyo Road, PMB 5320 Ibadan, Nigeria Regional Cocoa Symposium

TRAVEL ADVICE International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) Oyo Road, PMB 5320 Ibadan, Nigeria Regional Cocoa Symposium Contact at IITA: [email protected] CRIN contact: [email protected] WCF contact: [email protected] Before departure You need a valid passport, a visa (depending on your nationality), and a health certificate verifying an up-to-date yellow fever inoculation1. Citizens of countries belonging to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are exempted from the visa requirement. Kindly be aware that Ibadan is located in the Humid Tropics and that malaria is endemic in the area. It is advised to dress accordingly and take doctor’s advice before traveling. Obtaining a Nigerian Visa Applications for visas can be made at any Nigerian Embassy, Consulate, or High Commission in your country of residence or the nearest to you. The website https://portal.immigration.gov.ng/visa/freshVisa can give you more information. The application process may be time consuming. IITA will generate an invitation and visa support letter that will accompany your request. It is also possible to arrange for a visa on arrival if you reside in a country where Nigeria has no legal representation; please contact us for that one. You cannot buy a visa at the airport on arrival! Arriving at Lagos Airport Murtala Mohammed International Airport, Ikeja, is the port of disembarkation. Representatives from IITA will meet you after the baggage collection area to take you to the IITA vehicles. Airport assistance is also available (on request) to take you through immigration, customs and checking-in at a cost of USD 40 including arrival and departures. -

Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

The case of Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard Contact: Source: CIA factbook Laurent Fourchard Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), University of Ibadan Po Box 21540, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. Overview of Nigeria: Economic and Social Trends in the 20th Century During the colonial period (end of the 19th century – agricultural sectors. The contribution of agriculture to 1960), the Nigerian economy depended mainly on agri- the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 60 percent cultural exports and on proceeds from the mining indus- in the 1960s to 31 percent by the early 1980s. try. Small-holder peasant farmers were responsible for Agricultural production declined because of inexpen- the production of cocoa, coffee, rubber and timber in the sive imports and heavy demand for construction labour Western Region, palm produce in the Eastern Region encouraged the migration of farm workers to towns and and cotton, groundnut, hides and skins in the Northern cities. Region. The major minerals were tin and columbite from From being a major agricultural net exporter in the the central plateau and from the Eastern Highlands. In 1960s and largely self-sufficient in food, Nigeria the decade after independence, Nigeria pursued a became a net importer of agricultural commodities. deliberate policy of import-substitution industrialisation, When oil revenues fell in 1982, the economy was left which led to the establishment of many light industries, with an unsustainable import and capital-intensive such as food processing, textiles and fabrication of production structure; and the national budget was dras- metal and plastic wares.