Propaganda of Hatred and the Great Terror. a Nordic Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jorunn Bjørgum Veien Til Komintern Martin Tranmæl Og Det

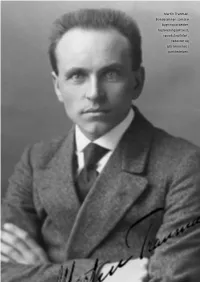

Martin Tranmæl. Bondesønnen som ble bygningsarbeider, fagforeningsaktivist, sosialistagitator , redaktør og grå eminense i partiledelsen. Jorunn BJørguM Veien til Komintern Martin Tranmæl og det internasjonale spørsmål 1914–19 Hvordan kan vi forklare at Martin Tranmæl i 1919 gikk inn for at Det norske Arbeiderparti skulle bryte opp fra den gamle sosialistiske 2. Inter nasjonalen og i stedet slutte seg til Komintern? Det er hovedproblemstil lingen i denne artikkelen.1 Martin Tranmæl var en ruvende lederskikkelse i norsk arbeiderbeve gelse i over to mannsaldre. Forut for 1918 var han opposisjonsleder. gjennom hele mellomkrigstiden var han Arbeiderpartiets reelle politiske leder. og i etterkrigstiden var han en sentral politisk bakspiller eller grå eminense i partiledelsen. Han var medlem av Arbeiderpartiets landsstyre fra 1906 og av sentralstyret fra 1918 og helt fram til 1963. I storparten av tiden var han også medlem av Los sekretariat og av samarbeids komiteen mellom Arbeiderpartiet og Lo.2 Han utøvde sitt lederskap dels gjennom de formelle organene han deltok i, dels gjennom stillingen som redaktør og dels gjennom personlig påvirkning på partiformennene oscar Torp og Einar gerhardsen, som han selv hadde rekruttert til parti ledelsen i 1923. Så hvordan kunne det ha seg at denne sentrale sosialdemokraten i 1919 gikk inn for at Arbeiderpartiet skulle melde seg inn i Lenins nye kommunistiske internasjonale? utgangspunktet var radikaliseringen av norsk arbeiderbevegelse under første verdenskrig, da Tranmæl stod i spissen for partiopposisjonen, den nye retning. Den overtok ledelsen av Arbeiderpartiet på landsmøtet i 1918 og fikk vedtatt sin parole revolu sjonær masseaksjon som partiets nye politiske strategi.3 Tranmæl ble ny partisekretær og hans nære venn og politiske medarbeider, Kyrre grepp, ny partiformann. -

Why the European Union Promotes Democracy Through Membership Conditionality Ryan Phillips

Why the European Union Promotes Democracy through Membership Conditionality Ryan Phillips Government & International Relations Department, Connecticut College, 270 Mohegan Avenue, New London, CT 06320, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Prepared for 2017 EUSA Conference – Miami, FL DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Abstract Explanations of why the European Union promotes democracy through membership conditionality provide different accounts of its normative rationale. Constructivists argue that the EU’s membership policy reflects a norm-driven commitment to democracy as fundamental to political legitimacy. Alternatively, rationalists argue that membership conditionality is a way for member states to advance their economic and security interests in the near abroad. The existing research, however, has only a weak empirical basis. A systematic consideration of evidence leads to a novel understanding of EU membership conditionality. The main empirical finding is that whereas the constructivist argument holds true when de facto membership criteria were first established in the 1960s, the rationalist argument more closely aligns with the evidence at the end of the Cold War when accession requirements were formally codified as part of the Copenhagen Criteria (1993). Keywords: democracy promotion, political conditionality, enlargement, European Union, membership Word Count: 7177 1 Introduction On October 12, 2012 in the Norwegian capital of Oslo, Thorbjørn Jagland declared, ‘The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2012 is to be awarded to the European Union. The Union and its forerunners have for over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe’ (Jagland 2012). In awarding the EU the Nobel Peace Prize, the former prime minister voiced a common view of the organization as well as its predecessors, namely that it has been a major force for the advancement of democracy throughout Europe. -

Nproliferation Review Is Unable to Russia & Republics Nuclear Industry, 5/25/94, P

Nuclear Developments 15 NEWLY-INDEPENDENT ST ATES 3/17/94 ARMENIA WITH THE FORMER A secondary agreement is signed in Mos- SOVIET UNION ARMENIA cow between Russian First Deputy Minis- ter Oleg Soskovets and Armenian Prime 4/4/94 Minister Grant Bagratyan regarding the The Romanian newspaper Romania Libera renovations and reactivation of the Metsamor publishes allegations that the former Soviet INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS nuclear power plant. The agreement will Union may have used a seismic weapon create an intergovernmental committee for called the Elipton to trigger a major earth- 2/94 the renovation project. Minatom and quake in Armenia. According to the article, Armenia’s Minister of Energy and Fuel Re- Gosatomnadzor will represent Russia on the U.S. military intelligence experts noted that sources Miron Sheshmanali reports that it committee, while the Armenian Energy the earthquake occurred at a time when the is essential for the rebuilding of Armenia’s Ministry and the Armenian State Director- Soviet authorities would have wanted to power generating industry to restart the ate for the Supervision of Nuclear Energy destroy Armenia's nuclear industry in or- nuclear power plant. will represent Armenia. Russia will pro- der to ensure the republic's continued de- Novosti, 5/2/94; in Russia & CIS Today, 5/2/94, vide nuclear fuel, engineering services, as- No. 0315, p. 9 (11154). pendence on the USSR. sistance in the development of a nuclear Oana Stanciulescu, Romania Libera (Bucharest), 4/ power management structure in Armenia, 4/94, p.1; in FBIS-SOV-94-068, 4/8/94, pp. 25-26 and technical servicing of the power station. -

Glendale Exhibits Explore Concept of Inherited Trauma of Armenian Genocide

MARCH 24, 2018 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVIII, NO. 35, Issue 4530 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Washington Armenian Aliyev Insists on Community Unites in ‘Historic Azeri Lands’ Support of Artsakh In Armenia BAKU (RFE/RL) — Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev has stood by his claims that much of By Aram Arkun modern-day Armenia lies in “historic Azerbaijani Mirror-Spectator Staff lands.” “I have repeatedly said and want to say once again that the territory of contemporary Armenia WASHINGTON — Upon the initiative of is historic Azerbaijani lands. There are numerous the representation of Artsakh in the United books and maps confirming that,” Aliyev said on States, the Armenian Assembly of America Monday, March 19, at the start of official celebra- and the Armenian National Committee of tions of Nowruz, the ancient Persian New Year America (ANCA) organized a reception and marked as a public holiday in Azerbaijan. banquet for the Armenian community on “The Azerbaijani youth must know this first and March 17 at the University Club in foremost. Let it know that most of modern-day Washington D. C. to honor the visiting del- Armenia is historic Azerbaijani lands. We will egation of the Republic of Artsakh led by never forget this,” he said. President Bako Sahakyan. Aliyev has repeatedly made such statements, The bilingual event was moderated by Annie Totah receives a medal from President Bako Sahakyan, while Aram Hamparian holds the medal he just got (photo: Aram Arkun) most recently on February 8. Speaking at a pre- Annie Simonian Totah, board member of election congress of his Yeni Azerbaycan party, he the Armenian Assembly, and Aram pledged to “return Azerbaijanis” to Yerevan, Hamparian, executive director of the two Armenian lobbying organizations of pointed out that the ANCA and the Syunik province and the area around Lake Sevan. -

From Archives of Vuchk-GPU-NKVD-KGB Chernobyl Tragedy in Documents and Materials (Summary)

From Archives of VUChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB Chernobyl Tragedy in Documents and Materials (Summary) Volodymyr Tykhyy General overview of the book The book "From archives of VUChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB. Chernobyl tragedy in documents and materials" (Z arhiviv VUCHK-GPU-NKVD-KGB. Chornobylska tragedia v dokumentakh ta materialakh, №1(16) 2001) was published by the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) in 2001. SSU is a natural continuation of the Soviet KGB (Committee of the State Security of the USSR), so SSU inherited KGB archives and disclosed some documents when the appropriate legislation was passed by the Parliament of Ukraine beginning in 1994 with the Law "On State Secrets". It is essential to note that on 10 December 2005 the book was also posted on the web-site of the SSU (http://www.sbu.gov.ua/sbu/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=39296&cat_id=46616). KGB is a unique source of information, because it worked "across the lines": it was subordinated neither to nuclear industry nor to army generals; it supervised activities of industry, government and municipal authorities, construction companies and cooperative shops alike. KGB officers collected information from all sources they deemed reliable, they often were able to cross-check it and then to present to higher levels of hierarchy - in KGB, Communist Party, Government of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. So, this information contained quite reliable facts, which were formulated without flatter - moreover, it was either "secret" or "top secret". Unfortunately, this does not mean that their reports were given any special attention - the system had its own inertia, and KGB was an integral part of the system. -

Stalinist Terror and Democracy: the 1937 Union Campaign

Stalinist Terror and Democracy: The 1937 Union Campaign WENDY GOLDMAN IN A PRISON CAMP IN THE 1930S, a young Soviet woman posed an anguished question in a poem about Stalinist terror: We must give an answer: Who needed The monstrous destruction of the generation That the country, severe and tender. Raised for twenty years in work and battle?^ Historians, united only by a commitment to do this question justice, differ sharply about almost every aspect of "the Great Terror":^ the intent of the state, the targets of repression, the role of external and internal pressures, the degree of centralized control, the number of victims, and the reaction of Soviet citizens. One long- prevailing view holds that the Soviet regime was from its inception a "terror" state. Its authorities, intent solely on maintaining power, sent a steady stream of people to their deaths in camps and prisons. The stream may have widened or narrowed over time, but it never stopped flowing. The Bolsheviks, committed to an antidemocratic ideology and thus predisposed to "terror," crushed civil society in order to wield unlimited power. Terror victimized all strata of a prostrate population.^ 1 would like to thank the American Council of Learned Societies for its support, and William Chase, Anton D'Auria, Donald Filtzer, J. Arch Getty, Lawrence Goldman, Jonathan Harris, Donna Harsch, Aleksei Kilichenkov, Marcus Rediker. Carmine Storella, and the members of the Working Class History Seminar in Pittsburgh for their comments and suggestions. ' Yelena Vladimirova, a Leningrad communist who was sent to the camps in the late 1930s, wrote the poem. -

Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Anthology of the international conference Bratislava 14. – 16. 11. 2007 Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Nation´s Memory Institute BRATISLAVA 2008 Anthology was published with kind support of The International Visegrad Fund. Visegrad Fund NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Cen- tral and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 14 – 16 November, 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia Anthology of the international conference Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Published by Nation´s Memory Institute Nám. SNP 28 810 00 Bratislava Slovakia www.upn.gov.sk 1st edition English language correction Anitra N. Van Prooyen Slovak/Czech language correction Alexandra Grúňová, Katarína Szabová Translation Jana Krajňáková et al. Cover design Peter Rendek Lay-out, typeseting, printing by Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška © Nation´s Memory Institute 2008 ISBN 978-80-89335-01-5 Nation´s Memory Institute 5 Contents DECLARATION on a conference NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 ..................................................................9 Conference opening František Mikloško ......................................................................................13 Jiří Liška ....................................................................................................... 15 Ivan A. Petranský ........................................................................................ -

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education The portrayal of the Russian Revolution of 1917 in the Norwegian labor movement A study of the editorials of the Social-Demokraten, 1915—1923 Anzhela Atayan Master’s thesis in Peace and Conflict Transformation – SVF-3901 June 2014 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Kari Aga Myklebost for helpful supervision with practical advice and useful comments, the Culture and Social Sciences Library, the Centre for Peace Studies and Ola Goverud Andersson for support. iii iv Morgen mot Russlands grense Jeg kommer fra dagen igår, fra vesten, fra fortidens land. Langt fremme en solstripe går mot syd. Det er morgenens rand. I jubel flyr toget avsted. Se grensen! En linje av ild. Bak den er det gamle brendt ned. Bak den er det nye blitt til. Jeg føler forventningens sang i hjertets urolige slag. Så skulde jeg også engang få møte den nye dag! Rudolf Nilsen v vi Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………….......1 1.1.Major terms and choice of period……...………………………………………………......1 1.2.Research questions…………………………………………………………………………2 1.3.Motivation and relevance for peace studies………………………………………………..3 1.4.Three editors: presentation…………………………………………………………………3 1.5.The development of the Norwegian labor press: a short description………………………6 1.6.The position of the Norwegian labor movement in Scandinavia…………………………..7 1.7.Structure of the thesis............................................................................................................8 Chapter 2. Previous studies and historical background………………………………………11 2.1. Previous studies…………………………………………………………………………..11 2.2. Historical background……………………………………………………………………14 2.2.1. The situation in Norway…………………………………………………………...14 2.2.2. Connections between the Bolsheviks and the Norwegian left…………….……....16 Chapter 3. -

Enemies of the People

Enemies of the people Gerhard Toewsy Pierre-Louis V´ezinaz February 15, 2019 Abstract Enemies of the people were the millions of intellectuals, artists, businessmen, politicians, professors, landowners, scientists, and affluent peasants that were thought a threat to the Soviet regime and were sent to the Gulag, i.e. the system of forced labor camps throughout the Soviet Union. In this paper we look at the long-run consequences of this dark re-location episode. We show that areas around camps with a larger share of enemies among prisoners are more prosperous today, as captured by night lights per capita, firm productivity, wages, and education. Our results point in the direction of a long-run persistence of skills and a resulting positive effect on local economic outcomes via human capital channels. ∗We are grateful to J´er^omeAdda, Cevat Aksoy, Anne Applebaum, Sam Bazzi, Sascha Becker, Catagay Bircan, Richard Blundell, Eric Chaney, Sam Greene, Sergei Guriev, Tarek Hassan, Alex Jaax, Alex Libman, Stephen Lovell, Andrei Markevich, Tatjana Mikhailova, Karan Nagpal, Elena Nikolova, Judith Pallot, Elena Paltseva, Elias Papaioannou, Barbara Petrongolo, Rick van der Ploeg, Hillel Rappaport, Ferdinand Rauch, Ariel Resheff, Lennart Samuelson, Gianluca Santoni, Helena Schweiger, Ragnar Torvik, Michele Valsecchi, Thierry Verdier, Wessel Vermeulen, David Yaganizawa-Drott, Nate Young, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. We also wish to thank seminar participants at the 2017 Journees LAGV at the Aix-Marseille School of Economics, the 2017 IEA Wold Congress in Mexico City, the 2017 CSAE conference at Oxford, the 2018 DGO workshop in Berlin, the 2018 Centre for Globalisation Research workshop at Queen Mary, the Migration workshop at CEPII in Paris, the Dark Episodes workshop at King's, and at SSEES at UCL, NES in Moscow, Memorial in Moscow, ISS-Erasmus University in The Hague, the OxCarre brownbag, the QPE lunch at King's, the Oxford hackaton, Saint Petersburg State University, SITE in Stockholm, and at the EBRD for their comments and suggestions. -

Tufts University the American Left And

TUFTS UNIVERSITY THE AMERICAN LEFT AND STALIN'S PURGES, 1936-38: FELLOW-TRAVELLERS AND THEIR ARGUMENTS UNDERGRADUATE HONORS THESIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY by SUSAN T. CAULFIELD DECEMBER 1979 CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. SHOW TRIALS AND PURGES IN THE SOVIET UNION, 1936-38 7 III. TYPOLOGY OF ARGUMENTS 24 IV. EXPLANATIONS .••.•• 64 V. EPILOGUE: THE NAZI-SOVIET PACT 88 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 95 I. INTRODUCTION In 1936, George Soule, an editor of the New Republic, described in that magazine the feelings of a traveller just returned from the Soviet Union: ••• After a week or so he begins to miss something. He misses the hope, the enthusiasm, the intellectual vigor, the ferment of change. In Russia people have the sense that something new and better is going to happen next week. And it usually does. The feeling is a little like the excitement that accompanied the first few weeks of the New Deal. But the Soviet New Deal has been going on longer, is proyiding more and more tangible results, and retains its vitality ..• For Soule, interest in the "Soviet New Deal" was an expression of dis- content with his own society; while not going so far as to advocate So- viet solutions to American problems, he regarded Soviet progress as proof that there existed solutions to those problems superior to those offered by the New Deal. When he and others on the American Left in the 1930's found the Soviet Union a source of inspiration, praised what they saw there, and spoke at times as if they had found utopia, the phenomenon was not a new one. -

Russian Military Thinking and Threat Perception: a Finnish View

CERI STRATEGY PAPERS N° 5 – Séminaire Stratégique du 13 novembre 2009 Russian Military Thinking and Threat Perception: A Finnish View Dr. Stefan FORSS The author is a Finnish physicist working as Senior Researcher at the Unit of Policy Planning and Research at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and as Adjunct Professor at the Department of Strategic and Defence Studies at the National Defence University in Helsinki. The views expressed are his own. Introduction “The three main security challenges for Finland today are Russia, Russia and Russia. And not only for Finland, but for all of us.”1 This quote is from a speech by Finnish Minister of Defence Jyri Häkämies in Washington in September 2007. His remarks were immediately strongly criticised as inappropriate and it was pointed out that his view didn’t represent the official position of the Finnish Government. Mr. Häkämies seemed, however, to gain in credibility a month later, when a senior Russian diplomat gave a strongly worded presentation about the security threats in the Baltic Sea area in a seminar organised by the Finnish National Defence University and later appeared several times on Finnish television.2 The message sent was that Finnish membership in NATO would be perceived as a military threat to Russia. This peculiar episode caused cold shivers, as it reminded us of unpleasant experiences during the post-war period. The Russian military force build-up and the war in Georgia in August 2008 was the ultimate confirmation for all of Russia’s neighbours, that the Soviet-style mindset is not a thing of the past. -

Naval Postgraduate School Thesis

NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS A STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN ACQUISITION OF THE FRENCH MISTRAL AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT WARSHIPS by Patrick Thomas Baker June 2011 Thesis Advisor: Mikhail Tsypkin Second Reader: Douglas Porch Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2011 Master‘s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS A Study of the Russian Acquisition of the French Mistral Amphibious Assault Warships 6. AUTHOR(S) Patrick Thomas Baker 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING N/A AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S.