A Suetonius Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

Julius Caesar

Working Paper CEsA CSG 168/2018 ANCIENT ROMAN POLITICS – JULIUS CAESAR Maria SOUSA GALITO Abstract Julius Caesar (JC) survived two civil wars: first, leaded by Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius; and second by himself and Pompeius Magnus. Until he was stabbed to death, at a senate session, in the Ides of March of 44 BC. JC has always been loved or hated, since he was alive and throughout History. He was a war hero, as many others. He was a patrician, among many. He was a roman Dictator, but not the only one. So what did he do exactly to get all this attention? Why did he stand out so much from the crowd? What did he represent? JC was a front-runner of his time, not a modern leader of the XXI century; and there are things not accepted today that were considered courageous or even extraordinary achievements back then. This text tries to explain why it’s important to focus on the man; on his life achievements before becoming the most powerful man in Rome; and why he stood out from every other man. Keywords Caesar, Politics, Military, Religion, Assassination. Sumário Júlio César (JC) sobreviveu a duas guerras civis: primeiro, lideradas por Cornélio Sula e Caio Mário; e depois por ele e Pompeius Magnus. Até ser esfaqueado numa sessão do senado nos Idos de Março de 44 AC. JC foi sempre amado ou odiado, quando ainda era vivo e ao longo da História. Ele foi um herói de guerra, como outros. Ele era um patrício, entre muitos. Ele foi um ditador romano, mas não o único. -

Brutus: the Noble Conspirator by Kathryn Tempest

2018-076 12 Sept. 2018 Brutus: The Noble Conspirator by Kathryn Tempest . New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2017. Pp. xiii, 314. ISBN 978–0–300–18009–1. Review by Kirsty Corrigan, University of Kent ([email protected]) There has been a recent resurgence 1 of interest in Marcus Junius Brutus (85–42 BC ), Julius Caesar’s most famous assassin. In Brutus: The Noble Conspirator , historian Kathryn Tempest (Roehampton Univ.) pursues further her interest in the Roman Republic. 2 She aims to use the relevant ancient evidence to go beyond the legend of Brutus created by Shakespeare and reveal the man in his his- torical context. Blending biographical with historical and literary analyses, she seeks to open a new perspective on factual details which, she admits, may not be novel in themselves (xi). Besides an introduction and conclusion, the book comprises eight chapters equipped with il- lustrations, maps, and endnotes. There is an extensive bibliography and a detailed but not com- prehensive index. 3 Two appendices helpfully summarize the order and nature of the events of a hectic political period (88–42 BC ). The author also compares the accounts of Plutarch, Appian, and Cassius Dio, the main ancient sources for the period. Though Tempest claims not to be bound to a linear historical narrative (14), chapters 1–7 in fact track the details of Brutus’s life chronologically. This has merit, since deviations from a chronological plan can cause the narrative to lose clarity. That said, the author does enliven her linear format by including quotations of primary sources as well as summaries and clarifications of contemporary political circumstances as, for example, in her discussion of the situation young nobles faced in the senate in the wake of Sulla's reforms in 81 BC (29–32). -

Julius Caesar Student Guide

proudly presents julius caesar STUDENT GUIDE Content created by Directors of Education Breona Conrad and Joshua Murphy contact: [email protected] with any questions, concerns, or more fascinating Shakespeare trivia Julius Caesar quick facts. MOST COMMON NOUNS VERBS ADJECTIVES men, Rome, night come, know, go noble, true, wrong If you were to look for the Ides on a calendar, you'll find it...kind A B O U T "Beware the Ides of March." ? T of. The Ides of March as we know it is March 15. The Romans THOS E "Et tu, Brute?" A N tracked time differently. They had three anchor points during F A M O U S These words were E any given month: "Nones" fell on the 5th or 7th, "Ides" fell on simply a creation of H the 13th or 15th, and "Kalends" noted the first of the following L I N E S . Shakespeare, not history. H W month; from these anchor points, Romans counted backwards. He wasn't far off, though. Brutus WAS So, instead of saying, "Hey, let's go catch a show on March 10," one of the main conspirators and is W E a Roman would say, "Hey, let's go catch a show 5 days from believed to have landed a blow to F H March Ides." The calendar was based on the moon cycle; the Caesar's thigh, but history does not note O Ides fell on the 15th in March, May, July, and October. Caesar having said these famous words. T And ,"beware..."? Kind of right. -

Knowledge and Tragedy 1

Knowledge and Tragedy 1 Knowledge and Tragedy: or why we shouldn’t share knowledge By Patrick Lambe When Julius Caesar walked into the Forum in Rome on that fateful March day in 44 BC, he was hard pressed by petitioners. Caesar was not in Rome often: he had spent much of the previous fourteen years enlarging the dominions of Rome, fighting a bitter civil war against those who thought him too powerful, and flirting with Cleopatra in Egypt. And he was about to head east, to Parthia, to fight another war. A lot of people wanted his attention before he left. One of the crowd was a philosophy teacher named Artemidorus. He knew of the plot to assassinate Caesar that very day, and had written the details of the plan and the names of the key conspirators onto a folded piece of papyrus. However, he noticed that whenever Caesar accepted a piece of paper from his petitioners, he handed it immediately, as all great men do, to one of his aides. Artemidorus came close, and as he handed over the papyrus, pleaded: “Read this one, Caesar, read it quickly and by yourself. I promise you it’s important and concerns you personally.” Devotees of just-in-time knowledge management would be pleased. The conspirators were already waiting inside the meeting hall with concealed knives. In fact, knowledge of the plot had started to leak out more widely. At Caesar’s home, one of Caesar’s servants, who had also discovered the plot, but who did not know when or how it was to be accomplished, was sitting by the entrance waiting for Caesar’s return, in order to warn him. -

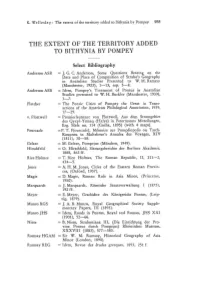

The Extent of the Territory Added to Bithynia by Pompey

K. Wellesley: The extent of me terricory added co Bithynia by Pompey 298 THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY ADDED TO BITHYNIA BY POMPEY Select Bibliography Anderson ASR = J. G. C. Anderson, Some Questions Bearing on the Date and PIace of Composition of Strabo's Geography in Anacolian Studies Presented to W. M. Ramsay (Manchester, 1923), 1-13, esp. 5-8. Anderson ASB . = Idem, Pompey's Treatment of Pontus in Anacolian Studies presented to W. H. Buckler (Manchester, 1939), . 3-7. Fletcher . = The Pontic Cities of Pompey the Great in Trans actions of the AInerican Philological Association, 1939, 17-29. v. FlottweIl = Premierleutnant von FlottweIl, Aus dem Stromgebiet des Qyzyl-Yrmaq (Halys) in Petermanns Mitteilungen, Erg. Heft no. 114 (Gotha, 1895) (with 4 maps). Fourcade =P. T. F(ourcade), Memoire sur Pompeiopolis ou Tasch Kouprou in Maltebrun's Annales des Voyages, XIV (1811), 30-58. Gelzer = M. Gelzer, Pompejus (München, 1949). Hirschfeld = O. Hirschfeld, Sitzungsberichte der Berliner Akademie, 1888, 863 H. RiceHolmes = T. Rice Holmes, The Roman Republic, II, 211-2, 434-5. iones = A. H. M. iones, Cities of the Eastern Roman Provin ces, (Oxford, 1937). Magie = D. Magie, Roman RuIe in Asia Minor, (Princecor" 1950). Marquardt = ]. Marquardt, Römische Staatsverwaltung I (1873), 192 H. Meyer = E. Meyer, Geschichte des Königreichs Pomos, (Leip zig, 1879). MunroRGS = J. A. R. Munro, Royal Geographical Society Supple mentary Papers, III (1893). Munro ]HS = Idem, Roads in Pontus, Royal and Roman, ]HS XXI (1901), 52-66. Niese = B. Niese, Straboniana III, (Die Einrichtung der Pro vinz Pontus durch Pompejus) Rheinisches Museum, XXXVIII (1883), 577-583. -

Takarazuka Grand Theater(HYOGO) Apr.2-May.10 2021

Takarazuka Grand Theater(HYOGO) Apr.2-May.10 2021 Historical Drama "Augustus: The Illustrious One" Written and directed by Daisuke Tabuchi Passionate Fantasy "Cool Beast!!" Written and directed by Daisuke Fujii On sale from: March 20, 2021, at 10:00 AM(JST) - Price SS Seat : 12,500 / S Seat : 8,800 / A Seat : 5,500 / B Seat : 3,500 Unit: Japanese Yen (tax included) Story --- "Augustus: The Illustrious One" Octavius became the first Roman emperor, who was granted the title of Augustus, meaning "the illustrious one". How did he become the successor to Caesar, who died without fulfilling his ambition? The year is 46 BC. The Roman triumph is held for Gaius Julius Caesar, who has returned to Rome after defeating his political opponent Pompeius in a long civil war. On that night, Caesar hosts a banquet to reconcile himself with the nobles who opposed him. Among the invited guests are Marcus Antonius who is considered a potential successor to Caesar; Cleopatra VII, the Egyptian queen and Caesar's lover; and Brutus who had been treated like a son to Caesar but turned against him during the civil war. When Caesar tells Brutus to give a toast, Pompeia, who is the daughter of the late Pompeius, appears at the banquet. She recklessly slashes at Caesar with her father's keepsake dagger. But she is stopped by Gaius Octavius, who is Caesar's greatnephew and a descendant of the gens Julia that is a Roman prestigious family. Octavius, who returned from his study trip to Greece, is attending the celebratory gathering with his assistant Agrippa. -

Sic Semper Tyrannis: Justification of Caesar’S Assassination

Sic Semper Tyrannis: Justification of Caesar’s Assassination Jeffrey Allen Thompson Seminar Paper Presented to the Department of History Western Oregon University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History Spring 2009 Approved_________________________________________Date___________ Approved_________________________________________Date___________ Hst 499: Prof. Max Geier & Prof. Narasingha Sil 1 -I- Sic Semper Tyrannis, Latin for ‘Thus unto tyrants,’ was famously spoken by John Wilkes Booth following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C. on April 13, 1865. Booth’s words harkened back to the assassination of another supposed tyrant two thousand years before, Gaius Julius Caesar. On the Ides of March, March 15, 44 B.C., Gaius Julius Caesar walked into the temple of Venus, atop Pompey’s Theater, where he was promptly stabbed by a conspiracy of over sixty prominent Romans. The leaders of the conspiracy took Caesar’s bloody robes onto the steps of the temple where they proclaimed that the tyrant was dead and rule had been restored to the Senate. Most prominent among them were the conspirators Marcus Junius Brutus (85-42 B.C.) and Gaius Cassius Longinus (C. 85-42 B.C.1). Caesar’s assassination marked the end of a nearly twenty-year period of Caesar’s ascent to power, which culminated in Caesar’s control of the Roman state. The assassination, although motivated by the patrician’s desire for power, was entirely within acceptable Roman beliefs about assassination and defense of the state. Caesar violated the Roman ideals of the first century B.C. about politics, namely, regnum and dominatio.2 This paper examines the justification of Caesar’s assassination from the perspective of Roman culture, history, and political ideals, as well as how Caesar’s assassination fits into the greater Roman ideals of murder, assassination, and justified murder. -

Wine and Drunkenness in Roman Society

WHEN TO SAY WHEN: WINE AND DRUNKENNESS IN ROMAN SOCIETY A thesis presented to the faculty at the University of Missouri in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree: master of arts by Damien Martin Dr. Raymond Marks, thesis supervisor May 2010 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled WHEN TO SAY WHEN: WINE AND DRUNKENNESS IN ROMAN SOCIETY presented by Damien Martin, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Raymond Marks Professor Barbara Wallach Professor George Gale ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Dr. Marks for organization, Dr. Wallach for perspective, Dr. Gale for expertise and Meredith for praising and prodding when each was necessary. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………................................................…….ii 1. Wine’s role in Roman life...........................................................................................1 Reasons and rules for drinking...................................................................................3 2. Convivium and Commissatio....................................................................................7 Cena Trimalchionis.................................................................................................16 3. Poetry: the Wine-Drinkers......................................................................................20 Horace.....................................................................................................................20 -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „Das Ende der römischen Republik im Historienfilm“ Verfasser Mag. Alexander Juraske angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) Wien, im Januar 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 310 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: 310 Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde Betreuer: emer. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Ekkehard Weber Gewidmet Dkfm. Heinz Juraske (1942-1998) Danksagung Die kontinuierliche Arbeit an einer Dissertation ist mitunter ein einsamer, von Rückschlägen und Krisen gekennzeichneter Arbeitsprozess. Im Laufe der Textproduktion kristallisiert sich eine Gruppe von Personen heraus, die in unterschiedlichster Weise dazu beitragen, dass das Ziel schlussendlich erreicht werden kann. In größter Dankbarkeit bin ich meinen beiden Betreuern emer. Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Ekkehard Weber und ao. Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Herbert Heftner verbunden, die mit ihrer Unterstützung das Entstehen dieser Arbeit ermöglichten. Prägend für meine wissenschaftliche Entwicklung waren einige Lehrer und Lehrerinnen, die mich an unterschiedlichen Stadien meiner wissenschaftlichen Initiation begleiteten, unter ihnen möchte ich Ass. Prof. Wolfgang Hameter hervorheben. Wie wichtig der Blick über den Tellerrand Österreichs hinaus ist, lehrten mich Dr. Martin Andreas Lindner und Dr. Anja Wieber, die als Rezeptionsspezialisten entscheidende Hilfestellungen gaben. Mein Dank gilt auch meiner Chefin Mag. Andrea Ramharter-Hanel sowie den beiden „Stützen“ des Instituts für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, AR Hertha Netuschill und Werner Niedermaier. Abschließend sei meiner Partnerin Katharina Krenn auf das herzlichste gedankt, die mit großer Leidenschaft und Kraft die Realisierung dieser Arbeit erst möglich machte und mir dabei half, die Hindernisse, die sich mir in den Weg stellten, zu überwinden. Ich hoffe sie in gleicher Weise bei zukünftigen Forschungen unterstützen zu können.