Saint Ignatius College Prep Saint Ignatius Model United Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

The Assassination of Julius Caesar 44 BC

Realizado por Elena Martín Gordón (IES Doñana, ALMONTE) The Assassination of Julius Caesar 44 B.C. Julius Caesar was a great general and an important leader in ancient Rome. His conquest of Gaul extended the Roman world to the North Sea, and he also conducted the first Roman invasion of Britain. Caesar began a civil war in 49 BC, and after that he became the master of the Roman world. He was proclaimed "dictator for life”, and he had the absolute power over the empire. After assuming control of the government, he began important reforms of Roman society and government. The Romans even named a month after him, the month of July for Julius Caesar. Most people liked Julius Caesar because he told To solve : the people that he could solve Rome's problems. Certainly, the resolver Republic had problems: crime was everywhere, taxes were very Taxes: high, and the people were hungry. impuestos Why did Julius Caesar have enemies among the rich and powerful? Among : entre As Julius Caesar became more powerful, and more popular with the people, To worry : leaders in the Senate began to worry . They were afraid that Julius Caesar preocuparse wanted to govern Rome as a king. The Roman senators did not want to return to To be afraid : the time of kings. They were afraid to lose their power. tener miedo, temer Julius Caesar had many enemies in Rome. Because of Julius Caesar's military victories, he was very popular with the Romans. His soldiers were very loyal to Loyal : leal, fiel their leader. -

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

LUCAN's CHARACTERIZATION of CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH By

LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY (Under the Direction of Thomas Biggs) ABSTRACT This thesis examines Caesar’s three extended battle exhortations in Lucan’s Bellum Civile (1.299-351, 5.319-364, 7.250-329) and the speeches that accompany them in an effort to discover patterns in the character’s speech. Lucan did not seem to develop a specific Caesarian style of speech, but he does make an effort to show the changing relationship between the General and his soldiers in the three scenes analyzed. The troops, initially under the spell of madness that pervades the poem, rebel. Caesar, through speech, is able to bring them into line. Caesar caters to the soldiers’ interests and egos and crafts his speeches in order to keep his army working together. INDEX WORDS: Lucan, Caesar, Bellum Civile, Pharsalia, Cohortatio, Battle Exhortation, Latin Literature LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY B.A., The College of Wooster, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth Talbot Neely All Rights Reserved LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY Major Professor: Thomas Biggs Committee: Christine Albright John Nicholson Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

Historical Background Notes

William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Historical Mr. Pogreba Background Helena High School The Roman World in 41 B.C.E. The Roman Republic ❖ The Roman Republic was founded in 509 B.C.E and ended in 27 B.C.E., replaced by the Roman Empire ❖ By 41 B.C.E. the Roman Republic controlled most of the Mediterranean and modern France. ❖ It was ruled by the Senate. Roman General and Politician Julius Caesar • Born to a middle class family in 100 B.C.E. • The greatest general in the history of Rome, he conquered modern France and put Egypt under Roman control. • He was appointed dictator for life in 44 B.C.E. • When he aspired to become King/ Emperor, he was murdered by the Senate on March 15, 44 B.C.E. Aftermath of Caesar’s Death ❖ His friend, Mark Antony, gave a speech over Caesar’s body that made the mob run wild in Rome, causing the assassins to flee. ❖ Eventually, the Roman territories are divided between three rulers in the Triumvirate, who divide the Roman territories between them. The Second Triumvirate ❖ The Roman territories were ruled by three men: ❖ Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) ❖ Octavian Caesar ❖ Marcus Lepidus ❖ They were threatened by the Parthian Empire and Sextus Pompey Octavian Lepidus Marc Antony 37 B.C.E. Territories of the Second Triumvirate Triumvir of Rome Marc Antony • Born in 83 B.C.E. • General under the command of Julius Caesar, he led the war against those who had killed Caesar. • He was the senior partner of the Trimuvirate, and given the largest territory to control in the East. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meaht to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

The Reception of Cato Uticensis and the Confederate Lost Cause

The Reception of Cato Uticensis and the Confederate Lost Cause On June 4, 1914, the 106th anniversary of former Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ birth, sculptor Moses Ezekiel’s monument to the Confederacy, called New South, was unveiled in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, DC. The monument is full of references to the ancient Roman world, especially in its sculptural style and the presence of a godly, pseudo- Minerva figure representing the New South. More curiously, Ezekiel inscribed the following quote from Book I of Lucan’s Pharsalia onto the monument underneath the seal of the Confederacy: “uictrix causa deis placuit sed uicta Catoni.” What does Cato have to do with the Lost Cause? Cato Uticensis was a Roman statesman, moralist, general, and avid defender of the Republic. Though he disliked both Pompey and Julius Caesar, he fought with Pompey against Caesar during the Civil War from 49 to 46 BCE. He became the de facto leader against Caesar after Pompey’s death in 48 but committed suicide in Utica after Caesar’s victory at Thrapsus. Robert Goar’s text detailing generally how a ‘legend’ formed around Cato in literature after his death from the first century BCE to the fifth century CE serves as the point of departure for this paper (Goar 1987). Goar concisely analyzes how the myth of Cato was adopted and transformed over time but does not analyze the impact or effects of this myth. The primary concern of this paper is on the legend’s impact— almost two millennia later. This paper explores the reception of the myths of both Cato Uticensis and his ancestor Cato Censorius by antebellum and postbellum Southern white Americans. -

The Letters of Cicero : the Whole Extant Correspondence in Chronological

Ex Libris C. K. OGDEN BOffN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY THE LETTERS OF CICERO VOL. Ill LONDON: G. BELL & SONS, LIMITED, PORTUGAL ST. LINCOLN'S INN, W.C. CAMBRIDGE: DEIGHTON, BELL& co. NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN CO. BOMBAY : A. H. WHEELER & CO. THE LETTERS OF CICERO THE WHOLE EXTANT CORRESPONDENCE IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY EVELYN S. SHUCKBURGH, M.A. LATE FELLOW OF EMMANUEL COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE AUTHOR OF A TRANSLATION OF HOLYBIUS, A HISTORY OF ROME. ETC IN FOUR VOLUMES VOL. III. B.C. 48-44 (FEBRUARY) LONDON G. BELL AND SONS, LTD. 1915 AND CO. CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. LETTERS IN VOLUME III VI LETTERS IN VOLUME III LETTERS IN VOLUME III Vll Vlll LETTERS IN VOLUME III Att. XIII. INTRODUCTION HPHE correspondence in this volume (January, B.C. 48- J- February, B.C. 44) opens with a letter to Atticus from Pompey's headquarters in Epirus. There are only nine letters during the fifteen or sixteen months Cicero at which intervene between Cicero's ' departure Pharsalia. One of these is from Cselius . August, B.C. 48. (p. 4), foreshadowing the disaster which soon afterwards befell that facile intelligence but ill-balanced character in- ; and one from Dolabella (p. 6), spired with a genuine wish in which Caesar shared that Cicero should withdraw in time from the chances and dangers of the war. Cicero's own letters deal mostly with the anxiety which he was feeling as to his property at home, which was at the mercy of the Csesarians, and, in case of Pompey's defeat, would doubtless be seized by the victorious party, except such of it as was capable of being concealed or held in trust by his friends. -

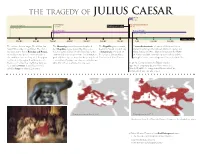

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

THE TR AGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR Transition 49–27 BC Coriolanus Caesar assassinated Roman Kingdom 494 BC Shakespeare’s play 44 BC 753–509 BC Roman Republic Roman Empire 509–49 BC 27 BC – 293 AD Roman Epochs 700 BC 600 BC 500 BC 400 BC 300 BC 200 BC 100 BC 1 AD 100 AD 200 AD The enforced vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, has The Monarchy is overthrown and replaced The Republic grows corrupt, A second triumvirate is formed of Octavius Caesar twins fathered by the god Mars. The stolen by a Republic, a government by the people, begins to flounder and decay. (Julius Caesar’s great-nephew), Marcus Lepidus, and and abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, headed by two consuls elected annually by the A triumvirate is formed of Mark Antony. In 27 BC, Mark Antony loses the Battle are fed by a woodpecker and nursed by a citizens and advised by a senate. A constitution Pompey the Great, Marcus of Actium and kills himself, Lepidus is exiled, and the she-wolf in a cave, the Lupercal. They grow gradually develops, centered on the principles of Crassus, and Julius Caesar. young Caesar becomes Augustus Caesar, Exalted One. up, found a city, argue, then Romulus kills a separation of powers and checks and balances. Remus and names the city Rome. OR it was All public offices are limited to one year. In 49 BC, Caesar crosses the Rubicon and is founded by Aeneas about this time. It is appointed temporary dictator three times; on ruled by kings for almost 250 years. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75