Barker Fariss a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in Partial Fulfillment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 Credits

ANTH 396-003 1 Andean Prehistory Summer 2017 Syllabus ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 credits) – Summer 2017 Meeting Place and Time: Robinson Hall A, Room A410, Tuesdays, 4:30 – 7:10 PM Instructor: Dr. Haagen Klaus Office: Robinson Hall B Room 437A E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-6568 Office Hours: T,R: 1:15- 3PM, or by appointment Web: http://soan.gmu.edu/people/hklaus - Required Textbook: Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge: New York. - Other readings available on Blackboard as PDFs. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND CONTENTS This seminar offers an updated synthesis of the development, achievements, and the material, organizational and ideological features of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Andean region of western South America. Together, they constituted one of the most remarkable series of civilizations of the pre-industrial world. Secondary objectives involve: appreciation of (a) the potential and limitations of the singular Andean environment and how human inhabitants creatively coped with them, (b) economic and political dynamism in the ancient Andes (namely, the coast of Peru, the Cuzco highlands, and the Titicaca Basin), (c) the short and long-term impacts of the Spanish conquest and how they relate to modern-day western South America, and (d) factors and conditions that have affected the nature, priorities, and accomplishments of scientific Andean archaeology. The temporal coverage of the course span some 14,000 years of pre-Hispanic cultural developments, from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Spanish conquest. The primary spatial coverage of the course roughly coincides with the western half (coast and highlands) of the modern nation of Peru – with special coverage and focus on the north coast of Peru. -

Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography

arts Article Inverted Worlds, Nocturnal States and Flying Mammals: Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography Aleksa K. Alaica Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Ursula Franklin Street, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2, Canada; [email protected] Received: 1 August 2020; Accepted: 10 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: Bats are depicted in various types of media in Central and South America. The Moche of northern Peru portrayed bats in many figurative ceramic vessels in association with themes of sacrifice, elite status and agricultural fertility. Osseous remains of bats in Moche ceremonial and domestic contexts are rare yet their various representations in visual media highlight Moche fascination with their corporeal form, behaviour and symbolic meaning. By exploring bat imagery in Moche iconography, I argue that the bat formed an important part of Moche categorical schemes of the non-human world. The bat symbolized death and renewal not only for the human body but also for agriculture, society and the cosmos. I contrast folk taxonomies and symbolic classification to interpret the relational role of various species of chiropterans to argue that the nocturnal behaviour of the bat and its symbolic association with the moon and the darkness of the underworld was not a negative sphere to be feared or rejected. Instead, like the representative priestesses of the Late Moche period, bats formed part of a visual repertoire to depict the cycles of destruction and renewal that permitted the cosmological continuation of life within North Coast Moche society. Keywords: bats; non-human animals; Moche; moon imagery; priestess; sacrifice; agriculture; fertility 1. -

Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru

Tearing Down Old Walls in the New World: Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru Megan Proffitt The country of Peru is an interesting area, bordered by mountains on one side and the ocean on the other. This unique environment was home to numerous pre-Columbian cultures, several of which are well- known for their creativity and technological advancements. These cul- tures include such groups as the Chavin, Nasca, Inca, and Moche. The last of these, the Moche, flourished from about 0-800 AD and more or less dominated Peru’s northern coast. During the 2001 summer archaeological field season, I was granted the opportunity to travel to Peru and participate in the excavation of the Huaca de Huancaco, a Moche palace. In recent years, as Dr. Steve Bourget and his colleagues have conducted extensive research and fieldwork on the site, the cul- tural identity of its inhabitants have come into question. Although Huancaco has long been deemed a Moche site, Bourget claims that it is not. In this paper I will give a general, widely accepted description of the Moche culture and a brief history of the archaeological work that has been conducted on it. I will then discuss the site of Huancaco itself and my personal involvement with it. Finally, I will give a brief account of the data that have, and have not, been found there. This information is crucial for the necessary comparisons to other Moche sites required by Bourget’s claim that Huancaco is not a Moche site, a claim that will be explained and supported in this paper. -

LD5655.V856 1988.G655.Pdf (8.549Mb)

CONTROL OF THE EFFECTS OF WIND, SAND, AND DUST BY THE CITADEL WALLS, IN CHAN CHAN, PERU bv I . S. Steven Gorin I Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Environmental Design and Planning I APPROVED: ( · 44”A, F. Q. Ventre;/Chairman ‘, _/— ;; Ä3“ 7 B. H. Evans E2 i;imgold ___ _H[ C. Miller 1115111- R. P. Schubert · — · December, 1988 Blacksburg, Virginia CONTROL OF THE EFFECTS OF WIND, SAND, AND DUST BY THE CITADEL WALLS IN CHAN CHAN, PERU by S. Steven Gorin Committee Chairman: Francis T. Ventre Environmental Design and Planning (ABSTRACT) Chan Chan, the prehistoric capital of the Chimu culture (ca. A.D. 900 to 1450), is located in the Moche Valley close to the Pacific Ocean on the North Coast of Peru. Its sandy desert environment is dominated by the dry onshore turbulent ' and gusty winds from the south. The nucleus of this large durban community built of adobe is visually and spacially ' dominated by 10 monumental rectilinear high walled citadels that were thought to be the domain of the rulers. The form and function of these immense citadels has been an enigma for scholars since their discovery by the Spanish ca. 1535. Previous efforts to explain the citadels and the walls have emphasized the social, political, and economic needs of the culture. The use of the citadels to control the effects of the wind, sand, and dust in the valley had not been previously considered. -

The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us About Northern Textile Production?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production? María Jesús Jiménez Díaz Universidad Complutense de Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Jiménez Díaz, María Jesús, "The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production?" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 403. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/403 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE EVOLUTION AND CHANGES OF MOCHE TEXTILE STYLE: WHAT DOES STYLE TELL US ABOUT NORTHERN TEXTILE PRODUCTION? María Jesús Jiménez Díaz Museo de América de Madrid / Universidad Complutense de Madrid Although Moche textiles form part of the legacy of one of the best known cultures of pre-Hispanic Peru, today they remain relatively unknown1. Moche culture evolved in the northern valleys of the Peruvian coast (Fig. 1) during the first 800 years after Christ (Fig. 2). They were contemporary with other cultures such us Nazca or Lima and their textiles exhibited special features that are reflected in their textile production. Previous studies of Moche textiles have been carried out by authors such as Lila O'Neale (1946, 1947), O'Neale y Kroeber (1930), William Conklin (1978) or Heiko Pruemers (1995). -

The Moche Lima Beans Recording System, Revisited

THE MOCHE LIMA BEANS RECORDING SYSTEM, REVISITED Tomi S. Melka Abstract: One matter that has raised sufficient uncertainties among scholars in the study of the Old Moche culture is a system that comprises patterned Lima beans. The marked beans, plus various associated effigies, appear painted by and large with a mixture of realism and symbolism on the surface of ceramic bottles and jugs, with many of them showing an unparalleled artistry in the great area of the South American subcontinent. A range of accounts has been offered as to what the real meaning of these items is: starting from a recrea- tional and/or a gambling game, to a divination scheme, to amulets, to an appli- cation for determining the length and order of funerary rites, to a device close to an accountancy and data storage medium, ending up with an ‘ideographic’, or even a ‘pre-alphabetic’ system. The investigation brings together structural, iconographic and cultural as- pects, and indicates that we might be dealing with an original form of mnemo- technology, contrived to solve the problems of medium and long-distance com- munication among the once thriving Moche principalities. Likewise, by review- ing the literature, by searching for new material, and exploring the structure and combinatory properties of the marked Lima beans, as well as by placing emphasis on joint scholarly efforts, may enhance the studies. Key words: ceramic vessels, communicative system, data storage and trans- mission, fine-line drawings, iconography, ‘messengers’, painted/incised Lima beans, patterns, pre-Inca Moche culture, ‘ritual runners’, tokens “Como resultado de la falta de testimonios claros, todas las explicaciones sobre este asunto parecen in- útiles; divierten a la curiosidad sin satisfacer a la razón.” [Due to a lack of clear evidence, all explana- tions on this issue would seem useless; they enter- tain the curiosity without satisfying the reason] von Hagen (1966: 157). -

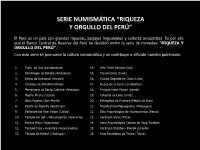

Presentación De Powerpoint

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

List of World Heritage Sites in America

Area SNo Site Location Criteria Year Description ha (acre) Agave The site consists of a living, working Jalisco, Mexico 34,019 Landscape and landscape of blue agave fields and 20°51′47″N Cultural: (84,060); Ancient distilleries in Tequila, El Arenal and 1 103°46′43″W / (ii), (iv), buffer zone 2006 Industrial Amatitán where tequila is produced. It 20.86306°N (v), (vi) 51,261 Facilities of reflects more than 2,000 years of 103.77861°W (126,670) Tequila commercial use of the agave plant. The park exhibits a wide array of CubaHolguín and 69,341 geology types. It contains many Alejandro de Guantánamo, (171,350); Natural: biological species, including 16 of 2 Humboldt Cuba buffer zone 2001 (ix), (x) Cuba's 28 endemic plant species, as National Park 20°27′N 75°0′W / 34,330 well as animal species such as the 20.450°N 75.000°W (84,800) endangered Cuban Solenodon. 3,000 Calakmul is an important Maya site Ancient Maya Campeche, Mexico Cultural: (7,400); with a number of well preserved City of 18°7′21″N 89°47′0″W / 3 (i), (ii), buffer zone 2002 monuments that bear testimony to Calakmul, 18.12250°N (iii), (iv) 147,195 twelve centuries of Maya cultural and Campeche 89.78333°W (363,730) political development. Founded in the early 16th century, Antigua was the capital of the Kingdom of Guatemala and its GuatemalaSacatepéquez cultural, economic, religious, political Department, Cultural: Antigua and educational centre until a 4 Guatemala (ii), (iii), 49 (120) 1979 Guatemala devastating earthquake in 1773. -

National History Bee Official Study Guide 2017-2018

8 OFFICIAL STUDY GUIDE 2017-18 PART 2 - World (PART 1 - U.S.) CANADA & CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA Ancient immigrants crossed the Bering land bridge and populated what is now Canada and the United States, then trickled down through the North American continent and to Central and South America. These peoples flourished until the arrival of European settlers. Europeans brought guns, germs and steel, decimating these original settlers, and colonized the continents. European influence significantly impacted the continent, permanently altering its ethnic makeup, customs and language, and it would be centuries before these regions began to shake off the reins of colonialism. CANADA Canada* Norsemen under Leif Eriksson established Inuit the first European settlement on the North Iroquois Confederacy American continent, L'Anse aux Meadows. War of Spanish Succession Quebec City, the first European settlement French & Indian War since Eriksson, was established by French Pontiac's Rebellion explorer Samuel de Champlain in 1608. The War of 1812 French were entrenched in fur trading across Dominion of Canada this region, and this caused a rivalry with the Royal Canadian Mounties British. The British controlled the Maritime Canadian Pacifi c Railway provinces, and the French colonists, known Klondike Gold Rush as Acadians, were expelled in the mid-18th North Pole exploration Roald Amundsen century. Many of these people migrated south to what is now Louisiana. Today, World War I Canada remains a self-governed dominion of Britain, although the province of Robert Service Quebec maintains much of its French character. World War II * Terms shown are for research purposes and not guaranteed to be on any offi cial test. -

Alfred Kroeber Died in Paris in His Eighty- O Fifth Year, Ending Six Decades of Continuous and Brilliant Pro- Ductivity

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES A L F R E D K ROE B ER 1876—1960 A Biographical Memoir by J U L I A N H . S TEWARD Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1962 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. ALFRED LOUIS KROEBER June II, 1876-October 5, i960 BY JULIAN H. STEWARD THE LAST DAY N OCTOBER 5, i960, Alfred Kroeber died in Paris in his eighty- o fifth year, ending six decades of continuous and brilliant pro- ductivity. His professional reputation was second to none, and he was warmly respected by his colleagues as the dean of anthropology. Kroeber's insatiable curiosity had not been curtailed, his scientific writing had not slackened, and his zest for living was undiminished. His last illness, resulting from, a heart condition which had been in- curred during the Second World War, came less than an hour before his death. The fullness of Kroeber's life was manifest in many ways.1 He xFor much of the personal information, I have drawn upon several unpublished manuscripts written by Kroeber in 1958 and 1959 for the Bancroft Library: "Early Anthropology at Columbia," "Teaching Staff (at California)," and the typescript of an interview. Mrs. Kroeber has rilled me in on many details of his personal life, especially before 1925 when I first knew him, and Professor Robert Heizer has helped round out the picture in many ways. Important insights into Kroeber's childhood and youth are provided by the late Dr. -

"Peruvian 2 Heritage Month" in Flor

FLORIDA HOUSE OF REP RESENTATIVE S HR 8071 2017 1 House Resolution 2 A resolution recognizing July 2017 as "Peruvian 3 Heritage Month" in Florida. 4 5 WHEREAS, Peru has a deep and rich heritage and is the home 6 of ancient cultures spanning from the Norte Chico civilization 7 in Caral, one of the oldest civilizations in the world, to the 8 Inca Empire, the largest state in Pre-Columbian America, and 9 WHEREAS, the Peruvian landscape is vibrant and varied, 10 featuring arid plains, the Andes Mountains, the tropical Amazon 11 Basin rainforest, and the Amazon River, and has influenced and 12 inspired the Peruvian history and culture, including the many 13 Peruvian Americans who have brought their talents and history to 14 this great state and nation, and 15 WHEREAS, counted among the many influential sons and 16 daughters of Peru are the fifth Secretary-General of the United 17 Nations, Javier Felipe Ricardo Pérez de Cuéllar Guerra; World 18 War II hero, Arthur Chin; artist and activist, Favianna 19 Rodriguez; American astronaut, Carlos Noriega; composer, Daniel 20 Alomia Robles; singer, Yma Sumac; economist, Hernando de Soto 21 Polar; actor and advocate, Q'orianka Kilcher; Chef, Emmanuel 22 Piqueras; photographer, Mario Testino; sportsman, Alex Olmedo; 23 and Olympian, Daniel Alarcon, and 24 WHEREAS, Florida is home to the largest Peruvian population 25 in the country and as educators, authors, community leaders, Page 1 of 2 hr8071-00 FLORIDA HOUSE OF REP RESENTATIVE S HR 8071 2017 26 business owners, activists, athletes, artists, musicians, -

Pots, Pans, and Politics: Feasting in Early Horizon Nepeña, Peru Kenneth Edward Sutherland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 Pots, Pans, and Politics: Feasting in Early Horizon Nepeña, Peru Kenneth Edward Sutherland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sutherland, Kenneth Edward, "Pots, Pans, and Politics: Feasting in Early Horizon Nepeña, Peru" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4572. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4572 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POTS, PANS, AND POLITICS: FEASTING IN EARLY HORIZON NEPEÑA, PERU A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Kenneth Edward Sutherland B.S. and B.A., Louisiana State University, 2015 August 2017 DEDICATION I wrote this thesis in memory of my great-grandparents, Sarah Inez Spence Brewer, Lillian Doucet Miller, and Augustine J. Miller, whom I was lucky enough to know during my youth. I also wrote this thesis in memory of my friends Heather Marie Guidry and Christopher Allan Trauth, who left this life too soon. I wrote this thesis in memory of my grandparents, James Edward Brewer, Matthew Roselius Sutherland, Bonnie Lynn Gaffney Sutherland, and Eloise Francis Miller Brewer, without whose support and encouragement I would not have returned to academic studies in the face of earlier adversity.