Six Women Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intangible Heritage(S): an Interplay of Design, Social and Cultural Critiques of the Built Environment

TANGIBLE - INTANGIBLE HERITAGE(S): AN INTERPLAY OF DESIGN, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CRITIQUES OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT • Paper / Proposal Title: ‘ARCHITECTS – WHERE IS YOUR VORTEX? VORTICISM, THE CITY AND URBAN EXPERIENCE • Author(s) Name: Dr. JONATHAN BLACK FRSA • University or Company Affiliation: KINGSTON SCHOOL OF ART, KINGSTON UNIVERSITY • Presentation Method. I would like to: i. present in person (with/without a written paper)* • Abstract (300 words): From its conception in the spring of 1914 the British avant garde art movement known as Vorticism was obsessed with the city and urban existence as central to the forward march of technologically innovative modernity. Indeed, the movement largely owed its very name to the American poet Ezra Pound having already identified London as the ‘great modern vortex’, the end point for all the energies of modern life and of British/Imperial power. My paper is rooted in many years of research into Vorticism and British Art before, during and after the First World War. It will focus on some of the many images that evoked the strikingly positive Vorticist vision of the city – one that as much looked to the example of vertically vertiginous New York as that by experimental thinkers on the European continent – by leading adherents of the movement such as: Wyndham Lewis, Edward Wadsworth, Frederick Etchells, Jessica Dismorr and Helen Saunders. Living in London much of their imagery was indebted to that city. However, examples will be discussed alongside a group of woodcut prints produced c. 1914-18 by Wadsworth inspired by the cities and industrial towns of his native Yorkshire such as Leeds, Bradford, Halifax and Huddersfield. -

Press Release NEW RHYTHMS Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Press Release New Exhibition performances of the Ballets Russes is brought to the fore through his bronze Firebird (1912). As well as exploring dance New Rhythms will investigate the artist’s wider NEW RHYTHMS fascination with motion, and the physical dynamism of bodily movement – new rhythms that are communicated Henri Gaudier-Brzeska: through sculpture and many of the artist’s drawings. The new dance trends that exploded onto pre‐war Art, Dance and Movement London stages and screens such as Apache dance from Paris, Tango and Ragtime and performances by the in London 1911-1915 Ballets Russes, will be represented through photographs, printed sources and film. The show culminates by asking Tuesday 17 March 2014 –– how Gaudier‐Brzeska’s dancers can inspire new rhythms now, through a contemporary dance and music Sunday 21 June 2015 commission. The work by Malgorzata Dzierzon, performed to new music commissioned from emerging In spring 2015 Kettle’s Yard will present a major composer Kate Whitley, will feature in the exhibition exhibition to mark the centenary of the death in the First through film. World War of the French-born sculptor and draughtsman This will be the final exhibition at Kettle’s Yard before Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891‐1915). Gaudier-Brzeska closing for a major development of the site and offers a moved permanently to London in January 1911. He chance for visitors to enjoy the house and an exhibition made a significant contribution to the development of intimately linked to it and the permanent collection. For modern sculpture, as one of the key members of the more about the development plans and off site activity Vorticist movement and by influencing a later generation see our website: www.kettlesyard.co.uk. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Download Our Guide To

BEST OF CORNWALL 2020 Marianne Stokes, née Priendlsberger 1855 - 1927 Lantern Light, 1888 Oil on canvas, 82.5 x 102 cm Penlee House Gallery & Museum Purchased by private treaty from Mr & Mrs Allan Amey with assistance from The Art Fund, The MLA/V&A Purchase Grant Fund and the Friends of Penlee A brief and incomplete history of ... art and artists in Cornwall By Andrea Breton Cornwall has always appealed to the creative type; a land of mists and megaliths, it combines a wide variety of landscape, from perfectly sanded coves to dramatic cliffs and breakers; bleak, haunted moors to lush vegetal valleys. There are picturesque harbours and grand country houses set in vast acreages. There are impressive landmarks from the past such as Tintagel Castle, St Michael’s Mount and more standing stones and Neolithic sites than you can shake a stick at. They exist happily alongside the present day futuristic domes of Eden, the stately grey bulk of Tate St Ives, old Mine chimneys (sensibly bestowed with World Heritage status) and the spoil heaps of the clay pits near St Austell. 35 BEST OF CORNWALL 2020 However there is more to Cornwall’s appeal than It was clear that luck landmarks. It is the geographical distance to the rest of was needed. Fortunately, the England; the quirk of geology which makes Cornwall Victorian age was coming somewhat longer than it is wide. Surrounded by the sea, and with it the age of steam it gives the county an all enveloping bright light, allegedly powered travel and the artists’ a couple of lux higher than the mainland. -

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue Location Title Auth. Last Notes Magazine - American Ancestors 4 issues. A local history book and is a record of the pioneer days of the 80 Years of Progress (Westlock, AB Committee Westlock District. Many photos and family stories. Family Alberta) name index. 929 pgs History of Kingman and Districts early years in the 1700s, (the AB A Harvest of Memories Kingman native peoples) 1854 the Hudson Bay followed by settlers. Family histories, photographs. 658 pgs Newspapers are arranged under the place of publication then under chronological order. Names of ethnic newspapers also AB Alberta Newspapers 1880 - 1982 Strathern listed. Photos of some of the newspapers and employees. 568 pgs A history of the Lyalta, Ardenode, Dalroy Districts. Contains AB Along the Fireguard Trail Lyalta photos, and family stories. Index of surnames. 343 pgs A local history book on a small area of northwestern Alberta from Flying Shot to South Wapiti and from Grovedale to AB Along the Wapiti Society Klondyke Trail. Family stories and many photos. Surname index. 431 pgs Alberta, formerly a part of the North-West Territories. An An Index to Birth, Marriage & Death AB Alberta index to Birth, Marriage and Death Registrations prior to Registrations prior to 1900 1900. 448 pgs AB Ann's Story Clifford The story of Pat Burns and his ranching empire. History of the Lower Peace River District. The contribution of AB Around the Lower Peace Gordon the people of Alberta, through Alberta Culture, acknowledged. 84 pgs Illustrated Starting with the early settlers and homesteaders, up to and AB As The Years Go By... -

Publications Catalogue 2015–16

Publications Catalogue 2015 –16 Vogue 100 New titles A Century of Style Robin Muir While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. It has assumed a central and vital role on the cultural stage, with a history that spans the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. Published to mark the magazine’s centenary, and accompanying a major exhibition, this book celebrates the twentieth century and beyond with an authoritative and discriminating eye. In more than 2,000 issues, British Vogue has acted as a cultural barometer, putting fashion in the context of the wider world – how we dress, how we entertain, what we eat, listen to, watch, who leads us, excites us and inspires us. The century’s most talented photographers, Lee Miller, Norman Parkinson, Cecil Beaton, Irving Penn, David Bailey, Snowdon and Mario Testino among them, have contributed to it. In 1916, when the First World War made transatlantic shipments of American Vogue impossible, its proprietor, Condé Nast, authorised a British edition. It was an immediate success, and over the following ten decades cover Provisional of uninterrupted publication continued to mirror its times – the austerity and optimism that followed two world wars, the ‘Swinging London’ scene 310 x 254 mm, 304 pages of the sixties, the radical seventies, the image-conscious eighties – and in Over 300 illustrations its second century remains at the cutting edge of photography and design. ISBN 978 1 85514 561 0 Decade by decade, Vogue 100 celebrates the greatest moments in Price £40 TBC (hardback) fashion, beauty and portrait photography. -

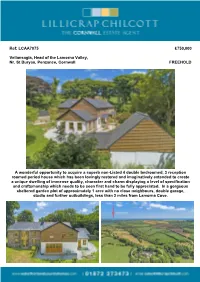

Ref: LCAA7075 £750,000

Ref: LCAA7075 £750,000 Vellansagia, Head of the Lamorna Valley, Nr. St Buryan, Penzance, Cornwall FREEHOLD A wonderful opportunity to acquire a superb non-Listed 4 double bedroomed, 3 reception roomed period house which has been lovingly restored and imaginatively extended to create a unique dwelling of immense quality, character and charm displaying a level of specification and craftsmanship which needs to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. In a gorgeous sheltered garden plot of approximately 1 acre with no close neighbours, double garage, studio and further outbuildings, less than 2 miles from Lamorna Cove. 2 Ref: LCAA7075 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: covered entrance porch into huge open-plan kitchen/dining room/family room (28’7” x 24’2”), larder, utility room, wc, triple aspect garden room, sitting room (26’4” x 16’6”) with woodburning stove. First Floor: approached off two separate staircases, galleried landing, master bedroom with en-suite bathroom, guest bedroom with en-suite shower room, circular staircase leads to secondary first floor landing, two further double bedrooms, family bathroom. Outside: double garage and workshop. Timber studio. Traditional stone outbuilding. Parking for numerous vehicles. Generous lawned gardens bounded by mature deciduous tree borders and pond. In all, approximately, 1 acre. DESCRIPTION • The availability of Vellansagia represents an incredibly exciting opportunity to acquire a truly unique family home comprising a lovingly restored non-Listed period house which has been transformed with a beautiful, contrasting large modern extension (more than doubling the size of the original house). Displaying a superb bespoke standard of finish and craftsmanship which needs to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. -

Detention Without Trial in the Second World War: Comparing the British and American Experiences A.W

Florida State University Law Review Volume 16 | Issue 2 Article 1 Summer 1988 Detention without Trial in the Second World War: Comparing the British and American Experiences A.W. Brian Simpson University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation A.W. B. Simpson, Detention without Trial in the Second World War: Comparing the British and American Experiences, 16 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 225 (2017) . http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol16/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 16 SUMMER 1988 NUMBER 2 DETENTION WITHOUT TRIAL IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR: COMPARING THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN EXPERIENCES A.W. BRIAN SIMPSON* National security has long been advanced as a justification for the abrogation of civil liberties. In this lecture, Professor Simpson examines through the analysis of particular cases how two nations dealt with these competing values in the internment without trial of their respective citizens during World War I. Condemning the secrecy and lack of accountability of the authorities responsible for protecting the nation, Simpson issues a call for vigilance and a warning that patterns and habits of respect for liberty will serve better than mere forms of procedure to effectively insure that liberties are not again abandoned to ill-founded claims of defense necessity. -

The Early Work on the Discovery of the Function of the Thymus, an Interview with Jacques Miller

Cell Death & Differentiation (2020) 27:396–401 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0462-y Q&A The early work on the discovery of the function of the thymus, an interview with Jacques Miller Jacques Miller1 Published online: 5 December 2019 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to ADMC Associazione Differenziamento e Morte Cellulare 2019. This article is published with open access This interview is part of a series of articles to mark the 25th anniversary of Cell Death and Differentiation. identified. Here, Cell Death and Differentiation asks Jac- ques Miller about his early work on thymus and T cells. CDD: Could you please describe your personal background, who were your parents, where were you born and what happened in your early years? My father and mother were both born in Paris in 1896. During the first World War (1914–1918), my father, Maurice Meunier, who spoke English fluently, acted as interpreter for the British troops who came to France. In 1919, he married and left with his new wife for China having found a job in a French bank in Peking (now known as Beijing). He spent some 22 years in China and Japan, eventually becoming Manager of the Franco-Chinese Bank in Shanghai. Besides English, he also spoke Spanish flu- ently, and learned Mandarin Chinese which he could write, and also Japanese which he wrote and spoke. In 1930, my mother returned to France by ship for health reasons. Finding that she was pregnant, she decided to have Fig. 1 Jacques (left), Gus Nossal (right) in 1967. -

The Book Can Be Downloaded Here. Every Corner Was a Picture 4Th

EVERY CORNER WAS A PICTURE 165 artists of Newlyn and the Newlyn Art Colony 1880–1900 a checklist compiled by George Bednar Fourth Edition 1 2 EVERY CORNER WAS A PICTURE 165 artists of Newlyn and the Newlyn Art Colony 1880–1900 Fourth Edition a checklist compiled by George Bednar ISBN 978 1 85022 192 0 1st edition published 1999 West Cornwall Art Archive 2nd edition © Truran 2004, revised 2005 3rd edition © Truran 2009, revised 2010, 2015 4th edition © Truran 2020 Published byTruran, an imprint of Tor Mark, United Downs Ind Est, St Day, Redruth TR16 5HY Cornwall www.truranbooks.co.uk Printed and bound in Cornwall by R. Booth Ltd, The Praze, Penryn, TR10 8AA Cover image: Walter Langley The Breadwinners/Newlyn Fishwives (Penlee House Gallery & Museum) Insert photographs: © Newlyn Artists Photograph Album, 1880s, Penlee House Gallery & Museum & Cornwall Studies Centre, Redruth ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I take this opportunity to thank Heather and Ivan Corbett, as well as Yvonne Baker, Steve Baxter, Alison Bevan (Director, RWA, formerly Director, Penlee House), John Biggs, Ursula M. Box Bodilly, Cyndie Campbell (National Gallery of Canada), Michael Carver, Michael Child, Robin Bateman, Michael Ginesi, Iris M. Green, Nik Hale, Barbara B. Hall, Melissa Hardie (WCAA), James Hart, Elizabeth Harvey-Lee, Peter Haworth, Katie Herbert (Penlee House, who suggested Truran), Jonathan Holmes, Martin Hopkinson, Ric and Lucy James, Tom and Rosamund Jordan, Alice Lock, Huon Mallallieu, David and Johnathan Messum, Stephen Paisnel, Margaret Powell, M.C. Pybus, Claus Pese, Brian D. Price, Richard Pryke, John Robertson, Frank Ruhrmund, Denise Sage, Peter Shaw, Alan Shears, Brian Stewart, David and Els Strandberg, Leon Suddaby, Sue and Geoffrey Suthers, Peter Symons, Barbara Thompson, David Tovey, Archie Trevillion, Ian Walker, Peter Waverly, John and Denys Wilcox, Christopher Wood, Laura Wortley, Nina Zborowska, and Valentine and John Foster Tonkin. -

Sheila Watson Fonds Finding Guide

SHEILA WATSON FONDS FINDING GUIDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JOHN M. KELLY LIBRARY | UNIVERSITY OF ST. MICHAEL’S COLLEGE 113 ST. JOSEPH STREET TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA M5S 1J4 ARRANGED AND DESCRIBED BY ANNA ST.ONGE CONTRACT ARCHIVIST JUNE 2007 (LAST UPDATED SEPTEMBER 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB Part I : Fonds – level description…………………………………………………………A Biographical Sketch HiStory of the Sheila WatSon fondS Extent of fondS DeScription of PaperS AcceSS, copyright and publiShing reStrictionS Note on Arrangement of materialS Related materialS from other fondS and Special collectionS Part II : Series – level descriptions………………………………………………………..B SerieS 1.0. DiarieS, reading journalS and day plannerS………………………………………...1 FileS 2006 01 01 – 2006 01 29 SerieS 2.0 ManuScriptS and draftS……………………………………………………………2 Sub-SerieS 2.1. NovelS Sub-SerieS 2.2. Short StorieS Sub-SerieS 2.3. Poetry Sub-SerieS 2.4. Non-fiction SerieS 3.0 General correSpondence…………………………………………………………..3 Sub-SerieS 3.1. Outgoing correSpondence Sub-SerieS 3.2. Incoming correSpondence SerieS 4.0 PubliShing records and buSineSS correSpondence………………………………….4 SerieS 5.0 ProfeSSional activitieS materialS……………………………………………………5 Sub-SerieS 5.1. Editorial, collaborative and contributive materialS Sub-SerieS 5.2. Canada Council paperS Sub-SerieS 5.3. Public readingS, interviewS and conference material SerieS 6.0 Student material…………………………………………………………………...6 SerieS 7.0 Teaching material………………………………………………………………….7 Sub-SerieS 7.1. Elementary and secondary school teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.2. UniverSity of BritiSh Columbia teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.3. UniverSity of Toronto teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.4. UniverSity of Alberta teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.5. PoSt-retirement teaching material SerieS 8.0 Research and reference materialS…………………………………………………..8 Sub-serieS 8.1. -

Download Our Exhibition Catalogue

FOREWORD Published to accompany the exhibition at We are delighted to welcome you to the second exhibition at Two Temple Place, London 26th January 2013 – 14th April 2013 Two Temple Place, Amongst Heroes: the artist in working Cornwall. Published in 2013 by Two Temple Place 2 Temple Place, London, wc2r 3bd The Bulldog Trust launched its Exhibition Programme at our Copyright © Two Temple Place headquarters on the Embankment in 2011. In welcoming the public to Two Temple Place we have three objectives: to raise Raising the Worker: awareness of museums and galleries around the UK by displaying Cornwall’s Artists and the Representation of Industry Copyright © Roo Gunzi part of their collections; to promote curatorial excellence by offering up-and-coming curators the opportunity to design a What are the Cornish boys to do? How Changing Industry Affected Cornwall’s Population high profile solo show with guidance from our experienced Copyright © Dr Bernard Deacon curatorial advisor; and to give the public the opportunity to Trustee of the Royal Institution of Cornwall and Honorary Research Fellow, University of Exeter visit and enjoy Two Temple Place itself. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library Two Temple Place was originally built as an office for William Waldorf Astor in the late 19th century and the Bulldog Trust isbn 978-0-9570628-1-8 have been fortunate to own the house since 1999. For our curators, Designed and produced by NA Creative devising a show for the ornate and intricately decorated space is a huge challenge that calls for imagination and ingenuity.