Conformal Maps from a 2-Torus to the 4-Sphere C Bohle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOME PROGRESS in CONFORMAL GEOMETRY Sun-Yung A. Chang, Jie Qing and Paul Yang Dedicated to the Memory of Thomas Branson 1. Confo

SOME PROGRESS IN CONFORMAL GEOMETRY Sun-Yung A. Chang, Jie Qing and Paul Yang Dedicated to the memory of Thomas Branson Abstract. In this paper we describe our current research in the theory of partial differential equations in conformal geometry. We introduce a bubble tree structure to study the degeneration of a class of Yamabe metrics on Bach flat manifolds satisfying some global conformal bounds on compact manifolds of dimension 4. As applications, we establish a gap theorem, a finiteness theorem for diffeomorphism type for this class, and diameter bound of the σ2-metrics in a class of conformal 4-manifolds. For conformally compact Einstein metrics we introduce an eigenfunction compactification. As a consequence we obtain some topological constraints in terms of renormalized volumes. 1. Conformal Gap and finiteness Theorem for a class of closed 4-manifolds 1.1 Introduction Suppose that (M 4; g) is a closed 4-manifold. It follows from the positive mass theorem that, for a 4-manifold with positive Yamabe constant, σ dv 16π2 2 ≤ ZM and equality holds if and only if (M 4; g) is conformally equivalent to the standard 4-sphere, where 1 1 σ [g] = R2 E 2; 2 24 − 2j j R is the scalar curvature of g and E is the traceless Ricci curvature of g. This is an interesting fact in conformal geometry because the above integral is a conformal invariant like the Yamabe constant. Typeset by AMS-TEX 1 2 CONFORMAL GEOMETRY One may ask, whether there is a constant 0 > 0 such that a closed 4-manifold M 4 has to be diffeomorphic to S4 if it admits a metric g with positive Yamabe constant and σ [g]dv (1 )16π2: 2 g ≥ − ZM for some < 0? Notice that here the Yamabe invariant for such [g] is automatically close to that for the round 4-sphere. -

Note on 6-Regular Graphs on the Klein Bottle Michiko Kasai [email protected]

Theory and Applications of Graphs Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 5 2017 Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle Michiko Kasai [email protected] Naoki Matsumoto Seikei University, [email protected] Atsuhiro Nakamoto Yokohama National University, [email protected] Takayuki Nozawa [email protected] Hiroki Seno [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag Part of the Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics Commons Recommended Citation Kasai, Michiko; Matsumoto, Naoki; Nakamoto, Atsuhiro; Nozawa, Takayuki; Seno, Hiroki; and Takiguchi, Yosuke (2017) "Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle," Theory and Applications of Graphs: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: 10.20429/tag.2017.040105 Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag/vol4/iss1/5 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theory and Applications of Graphs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle Authors Michiko Kasai, Naoki Matsumoto, Atsuhiro Nakamoto, Takayuki Nozawa, Hiroki Seno, and Yosuke Takiguchi This article is available in Theory and Applications of Graphs: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag/vol4/iss1/5 Kasai et al.: 6-regular graphs on the Klein bottle Abstract Altshuler [1] classified 6-regular graphs on the torus, but Thomassen [11] and Negami [7] gave different classifications for 6-regular graphs on the Klein bottle. In this note, we unify those two classifications, pointing out their difference and similarity. -

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

Non-Linear Elliptic Equations in Conformal Geometry, by S.-Y

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 44, Number 2, April 2007, Pages 323–330 S 0273-0979(07)01136-6 Article electronically published on January 5, 2007 Non-linear elliptic equations in conformal geometry, by S.-Y. Alice Chang, Z¨urich Lectures in Advanced Mathematics, European Mathematical Society, Z¨urich, 2004, viii+92 pp., US$28.00, ISBN 3-03719-006-X A conformal transformation is a diffeomorphism which preserves angles; the differential at each point is the composition of a rotation and a dilation. In its original sense, conformal geometry is the study of those geometric properties pre- served under transformations of this type. This subject is deeply intertwined with complex analysis for the simple reason that any holomorphic function f(z)ofone complex variable is conformal (away from points where f (z) = 0), and conversely, any conformal transformation from one neighbourhood of the plane to another is either holomorphic or antiholomorphic. This provides a rich supply of local conformal transformations in two dimensions. More globally, the (orientation pre- serving) conformal diffeomorphisms of the Riemann sphere S2 are its holomorphic automorphisms, and these in turn constitute the non-compact group of linear frac- tional transformations. By contrast, the group of conformal diffeomorphisms of any other compact Riemann surface is always compact (and finite when the genus is greater than 1). Implicit here is the notion that a Riemann surface is a smooth two-dimensional surface together with a conformal structure, i.e. a fixed way to measure angles on each tangent space. There is a nice finite dimensional structure on the set of all inequivalent conformal structures on a fixed compact surface; this is the starting point of Teichm¨uller theory. -

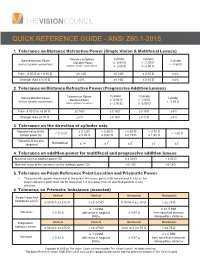

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Graphs on Surfaces, the Generalized Euler's Formula and The

Graphs on surfaces, the generalized Euler's formula and the classification theorem ZdenˇekDvoˇr´ak October 28, 2020 In this lecture, we allow the graphs to have loops and parallel edges. In addition to the plane (or the sphere), we can draw the graphs on the surface of the torus or on more complicated surfaces. Definition 1. A surface is a compact connected 2-dimensional manifold with- out boundary. Intuitive explanation: • 2-dimensional manifold without boundary: Each point has a neighbor- hood homeomorphic to an open disk, i.e., \locally, the surface looks at every point the same as the plane." • compact: \The surface can be covered by a finite number of such neigh- borhoods." • connected: \The surface has just one piece." Examples: • The sphere and the torus are surfaces. • The plane is not a surface, since it is not compact. • The closed disk is not a surface, since it has a boundary. From the combinatorial perspective, it does not make sense to distinguish between some of the surfaces; the same graphs can be drawn on the torus and on a deformed torus (e.g., a coffee mug with a handle). For us, two surfaces will be equivalent if they only differ by a homeomorphism; a function f :Σ1 ! Σ2 between two surfaces is a homeomorphism if f is a bijection, continuous, and the inverse f −1 is continuous as well. In particular, this 1 implies that f maps simple continuous curves to simple continuous curves, and thus it maps a drawing of a graph in Σ1 to a drawing of the same graph in Σ2. -

WHAT IS Q-CURVATURE? 1. Introduction Throughout His Distinguished Research Career, Tom Branson Was Fascinated by Con- Formal

WHAT IS Q-CURVATURE? S.-Y. ALICE CHANG, MICHAEL EASTWOOD, BENT ØRSTED, AND PAUL C. YANG In memory of Thomas P. Branson (1953–2006). Abstract. Branson’s Q-curvature is now recognized as a fundamental quantity in conformal geometry. We outline its construction and present its basic properties. 1. Introduction Throughout his distinguished research career, Tom Branson was fascinated by con- formal differential geometry and made several substantial contributions to this field. There is no doubt, however, that his favorite was the notion of Q-curvature. In this article we outline the construction and basic properties of Branson’s Q-curvature. As a Riemannian invariant, defined on even-dimensional manifolds, there is apparently nothing special about Q. On a surface Q is essentially the Gaussian curvature. In 4 dimensions there is a simple but unrevealing formula (4.1) for Q. In 6 dimensions an explicit formula is already quite difficult. What is truly remarkable, however, is how Q interacts with conformal, i.e. angle-preserving, transformations. We shall suppose that the reader is familiar with the basics of Riemannian differ- ential geometry but a few remarks on notation are in order. Sometimes, we shall write gab for a metric and ∇a for the corresponding connection. Let us write Rab and R for the Ricci and scalar curvatures, respectively. We shall use the metric to ‘raise and lower’ indices in the usual fashion and adopt the summation convention whereby one implicitly sums over repeated indices. Using these conventions, the Laplacian is ab a the differential operator ∆ ≡ g ∇a∇b = ∇ ∇a. A conformal structure on a smooth manifold is a metric defined only up to smoothly varying scale. -

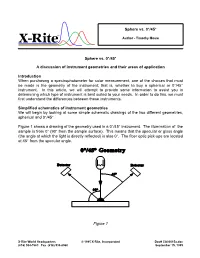

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

The Wave Equation on Asymptotically Anti-De Sitter Spaces

THE WAVE EQUATION ON ASYMPTOTICALLY ANTI-DE SITTER SPACES ANDRAS´ VASY Abstract. In this paper we describe the behavior of solutions of the Klein- ◦ Gordon equation, (g + λ)u = f, on Lorentzian manifolds (X ,g) which are anti-de Sitter-like (AdS-like) at infinity. Such manifolds are Lorentzian ana- logues of the so-called Riemannian conformally compact (or asymptotically hyperbolic) spaces, in the sense that the metric is conformal to a smooth Lorentzian metricg ˆ on X, where X has a non-trivial boundary, in the sense that g = x−2gˆ, with x a boundary defining function. The boundary is confor- mally time-like for these spaces, unlike asymptotically de Sitter spaces studied in [38, 6], which are similar but with the boundary being conformally space- like. Here we show local well-posedness for the Klein-Gordon equation, and also global well-posedness under global assumptions on the (null)bicharacteristic flow, for λ below the Breitenlohner-Freedman bound, (n − 1)2/4. These have been known under additional assumptions, [8, 9, 18]. Further, we describe the propagation of singularities of solutions and obtain the asymptotic behavior (at ∂X) of regular solutions. We also define the scattering operator, which in this case is an analogue of the hyperbolic Dirichlet-to-Neumann map. Thus, it is shown that below the Breitenlohner-Freedman bound, the Klein-Gordon equation behaves much like it would for the conformally related metric,g ˆ, with Dirichlet boundary conditions, for which propagation of singularities was shown by Melrose, Sj¨ostrand and Taylor [25, 26, 31, 28], though the precise form of the asymptotics is different. -

Math 865, Topics in Riemannian Geometry

Math 865, Topics in Riemannian Geometry Jeff A. Viaclovsky Fall 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Lecture 1: September 4, 2007 4 2.1 Metrics, vectors, and one-forms . 4 2.2 The musical isomorphisms . 4 2.3 Inner product on tensor bundles . 5 2.4 Connections on vector bundles . 6 2.5 Covariant derivatives of tensor fields . 7 2.6 Gradient and Hessian . 9 3 Lecture 2: September 6, 2007 9 3.1 Curvature in vector bundles . 9 3.2 Curvature in the tangent bundle . 10 3.3 Sectional curvature, Ricci tensor, and scalar curvature . 13 4 Lecture 3: September 11, 2007 14 4.1 Differential Bianchi Identity . 14 4.2 Algebraic study of the curvature tensor . 15 5 Lecture 4: September 13, 2007 19 5.1 Orthogonal decomposition of the curvature tensor . 19 5.2 The curvature operator . 20 5.3 Curvature in dimension three . 21 6 Lecture 5: September 18, 2007 22 6.1 Covariant derivatives redux . 22 6.2 Commuting covariant derivatives . 24 6.3 Rough Laplacian and gradient . 25 7 Lecture 6: September 20, 2007 26 7.1 Commuting Laplacian and Hessian . 26 7.2 An application to PDE . 28 1 8 Lecture 7: Tuesday, September 25. 29 8.1 Integration and adjoints . 29 9 Lecture 8: September 23, 2007 34 9.1 Bochner and Weitzenb¨ock formulas . 34 10 Lecture 9: October 2, 2007 38 10.1 Manifolds with positive curvature operator . 38 11 Lecture 10: October 4, 2007 41 11.1 Killing vector fields . 41 11.2 Isometries . 44 12 Lecture 11: October 9, 2007 45 12.1 Linearization of Ricci tensor .