Turkey's Internal Other: Embodiments of Taşra in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkey in Transition: the Dynamics of Domestic and Foreign Politics

EXCERPTED FROM Turkey in Transition: The Dynamics of Domestic and Foreign Politics edited by Gürkan Çelik and Ronald H. Linden Copyright © 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62637-827-8 hc 1800 30th Street, Suite 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com Contents List of Tables and Figures vii Preface ix Turkey at a Glance xi 1 Turkey at a Turbulent Time, Ronald H. Linden and Gürkan Çelik 1 Part 1 Dynamics at Home 2 Domestic Politics in the AKP Era, Gürkan Çelik 19 3 Gains and Strains in the Economy, Gürkan Çelik and Elvan Aktaş 39 4 The Geopolitics of Energy, Mustafa Demir 55 5 Militarization of the Kurdish Issue, Joost Jongerden 69 6 The Diyanet and the Changing Politics of Religion, Nico Landman 81 v vi Contents 7 The Fragmentation of Civil Society, Gürkan Çelik and Paul Dekker 95 8 Women in the “New” Turkey, Jenny White 109 Part 2 Dynamics Abroad 9 Changes and Dangers in Turkey’s World, Ronald H. Linden 125 10 Erdoğan’s Foreign Policy: The Role of Personality and Identity, Henri J. Barkey 147 11 The Crisis in US-Turkish Relations, Aaron Stein 163 12 Turkey in the Middle East, Bill Park 185 13 Russian-Turkish Relations at a Volatile Time, Joris Van Bladel 201 14 Turkey and Europe: Alternative Scenarios, Hanna-Lisa Hauge, Funda Tekin, and Wolfgang Wessels 215 15 Eurocentrism in Migration Policy, Juliette Tolay 231 Part 3 Conclusion 16 Transition to What? Gürkan Çelik and Ronald H. -

Three Monkeys

THREE MONKEYS (Üç Maymun) Directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan Winner Best Director Prize, Cannes 2008 Turkey / France/ Italy 2008 / 109 minutes / Scope Certificate: 15 new wave films Three Monkeys Director : Nuri Bilge Ceylan Producer : Zeynep Özbatur Co-producers: Fabienne Vonier Valerio De Paolis Cemal Noyan Nuri Bilge Ceylan Scriptwriters : Ebru Ceylan Ercan Kesal Nuri Bilge Ceylan Director of Photography : Gökhan Tiryaki Editors : Ayhan Ergürsel Bora Gökşingöl Nuri Bilge Ceylan Art Director : Ebru Ceylan Sound Engineer : Murat Şenürkmez Sound Editor : Umut Şenyol Sound Mixer : Olivier Goinard Production Coordination : Arda Topaloglu ZEYNOFILM - NBC FILM - PYRAMIDE PRODUCTIONS - BIM DISTRIBUZIONE In association with IMAJ With the participation of Ministry of Culture and Tourism Eurimages CNC COLOUR – 109 MINUTES - HD - 35mm - DOLBY SR SRD - CINEMASCOPE TURKEY / FRANCE / ITALY new wave films Three Monkeys CAST Yavuz Bingöl Eyüp Hatice Aslan Hacer Ahmet Rıfat Şungar İsmail Ercan Kesal Servet Cafer Köse Bayram Gürkan Aydın The child SYNOPSIS Eyüp takes the blame for his politician boss, Servet, after a hit and run accident. In return, he accepts a pay-off from his boss, believing it will make life for his wife and teenage son more secure. But whilst Eyüp is in prison, his son falls into bad company. Wanting to help her son, Eyüp’s wife Hacer approaches Servet for an advance, and soon gets more involved with him than she bargained for. When Eyüp returns from prison the pressure amongst the four characters reaches its climax. new wave films Three Monkeys Since the beginning of my early youth, what has most intrigued, perplexed and at the same time scared me, has been the realization of the incredibly wide scope of what goes on in the human psyche. -

OSW COMMENTARY NUMBER 275 1 from the Period of the Late Ottoman Empire1

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 274 | 26.06.2018 www.osw.waw.pl Cadres decide everything – Turkey’s reform of its military Mateusz Chudziak Over the last two years, the Turkish Armed Forces (Türk Silahlı Kuvvetlerı – TSK) have been sub- ject to transformations with no precedent in the history of Turkey as a republic. The process of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) subordinating the army to civilian government has accelerated following the failed coup that took place on 15 July 2016. The government has managed to take away the autonomy of the armed forces which, while retaining their enor- mous significance within the state apparatus, ceased to be the main element consolidating the old Kemalist elites. However, the unprecedented scale of the purges and the introduc- tion of formal civilian control of the military are merely a prelude to a much more profound change intended to create a brand new military, one that would serve the authorities and be composed of a new type of personnel – individuals from outside the army’s traditional power base. This reflects the reshuffle of the elites that happened during AKP’s rule. However, due to the fact that the TSK are a highly complex structure and the political situation both in Turkey itself and in its neighbourhood is tense, the military needs to retain its signif- icance within the state system. Military actions are being carried out in northern Syria and in the south-eastern part of Turkey. In a situation of profound distrust between the political leadership and the military, the government is trying to impact the internal divisions within the TSK by favouring anti-Western, pro-Russian and nationalist groups. -

The Turkish Sonderweg: Erdoğan's New Turkey And

IPC–MERCATOR POLICY BRIEF February 2020 THE TURKISH SONDERWEG: ERDOĞAN’S NEW TURKEY AND ITS ROLE IN THE GLOBAL ORDER Aslı Aydıntaşbaş THE TURKISH SONDERWEG: ERDOĞAN’S NEW TURKEY AND ITS ROLE IN THE GLOBAL ORDER About the Istanbul Policy Center-Sabancı University-Stiftung Mercator Initiative The Istanbul Policy Center–Sabancı University–Stiftung Mercator Initiative aims to strengthen the academic, political, and social ties between Turkey and Germany as well as Turkey and Europe. The Initiative is based on the premise that the acquisition of knowledge and the exchange of people and ideas are preconditions for meeting the challenges of an increasingly globalized world in the 21st century. The Initiative focuses on two areas of cooperation, EU/German-Turkish relations and climate change, which are of essential importance for the future of Turkey and Germany within a larger European and global context. 2 | FEBRUARY 2020 | IPC–MERCATOR POLICY BRIEF Introduction an emphasis on the social, economic, and political attributes that distinguish Germany from much of the rest of Europe. Similarly, Turkey is an exception About an hour’s drive north of Istanbul on a newly in its region, too, with an imperial past and resur- built highway stands the city’s new airport. “This is gent ambitions. These unique characteristics in do- not an airport but a monument to victory,” Turkish mestic and foreign policy have shaped Erdoğan’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said at its inaugu- New Turkey. ration on October 29, 2018—incidentally, a day that also marked the 95th anniversary of the founding of Clues for Turkey’s Sonderweg can be found behind the Republic of Turkey. -

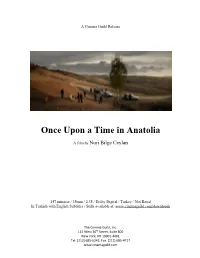

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

A Cinema Guild Release Once Upon a Time in Anatolia A film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan 157 minutes / 35mm / 2.35 / Dolby Digital / Turkey / Not Rated In Turkish with English Subtitles / Stills available at: www.cinemaguild.com/downloads The Cinema Guild, Inc. 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800 New York, NY 10001‐4061 Tel: (212) 685‐6242, Fax: (212) 685‐4717 www.cinemaguild.com Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Synopsis Late one night, an array of men- a police commissioner, a prosecutor, a doctor, a murder suspect and others- pack themselves into three cars and drive through the endless Anatolian country side, searching for a body across serpentine roads and rolling hills. The suspect claims he was drunk and can’t quite remember where the body was buried; field after field, they dig but discover only dirt. As the night draws on, tensions escalate, and individual stories slowly emerge from the weary small talk of the men. Nothing here is simple, and when the body is found, the real questions begin. At once epic and intimate, Ceylan’s latest explores the twisted web of truth, and the occasional kindness of lies. About the Film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia was the recipient of the Grand Prix at the Cannes film festival in 2011. It was an official selection of New York Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Biography: Born in Bakırköy, Istanbul on 26 January 1959, Nuri Bilge Ceylan spent his childhood in Yenice, his father's hometown in the North Aegean province of Çanakkale. -

Secularist Divide and Turkey's Descent Into Severe Polarization

One The Islamist- Secularist Divide and Turkey’s Descent into Severe Polarization senem aydın- düzgİt n multiple different measures of polarization, Turkey today is one of Othe most polarized nations in the world.1 Deep ideological and policy- based disagreements divide its political leaders and parties; Turkish so- ciety, too, is starkly polarized on the grounds of both ideology and social distance.2 This chapter focuses on the bases and manifestations of polar- ization in Turkey, the main reasons behind its increase, and its ramifica- tions for the future of democracy and governance in the country. The current dominant cleavage between secularists and Islamists has its roots in a series of reforms intended to secularize and modernize the coun- try after the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923. These reforms created a deep division within Turkish society, but until the beginning of the twenty- first century, the secularist elite dominated key state institu- tions such as the military, allowing it to repress conservative groups and thus keep conflict over the soul of Turkey from coming into the open. Since 2002, however, the remarkable electoral success of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi; AKP) has brought the Islamist- secularist divide to the fore. Despite the AKP’s initial moderation, several developments, including 17 Carothers-O’Donohue_Democracies Divided_i-viii_1-311.indd 17 7/24/19 10:32 AM 18 SENEM AYDIN- DÜZGI˙T the collapse of the European Union (EU) accession process, the success of polarization as an electoral strategy, and undemocratic threats from the secularist state establishment, pushed the AKP toward increasingly populist, divisive rhetoric and politics, beginning with the 2007 general elections. -

III. Turkey's Search for Stability and Legitimacy in 2016

european security 151 III. Turkey’s search for stability and legitimacy in 2016 michael sahlin Has Turkey, long seen as a pillar of stability in a sensitive geographical and geopolitical location, now become a source of instability and unpredicta- bility in the Middle East, for Europe and for the transatlantic community? During 2016 a combination of external geopolitical events and regime decisions accelerated trends in Turkish domestic and foreign policies, and a series of disruptive events led to several open questions regarding Turkey’s ongoing transformation. In many ways 2016 was for Turkey and its people—Turks, Kurds and others—a true annus horribilis, with a string of dramatic events and existen- tial threats shaking the country: large-scale terror attacks against civilian and military targets; a lethal coup d’état attempt followed by a massive purge of the alleged plotters as well as of a huge number of other suspected anti-regime circles in state and society; large-scale warfare between the Turkish security forces and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK); and mil- itary involvement in northern Syria. These events and others had a highly problematic impact on the Turkish economy and on Turkey’s traditional ties with both the European Union (EU) and the United States, which in turn affected Turkey’s crisis-ridden policies and resulted in policy changes relat- ing to Syria and Iraq. At the close of 2016, therefore, events during the year (and before) had resulted in a great deal of uncertainty going forward. Further to this, the politically polarizing issue of introducing a presidential system, in breach of Turkey’s republican parliamentary tradition and within a post-coup state of emergency climate and continuing comprehensive purges, raised further questions regarding what would be the new normal in the ‘New Turkey’ conceived by President Erdoğan and his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). -

Anadolu Türkülerinin Anadolu Pop- Rock Müzik Türüne Uyarlanmasinin Halkbilimsel Incelenmesi

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TÜRK DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI TÜRK HALK EDEBİYATI BİLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZİ ANADOLU TÜRKÜLERİNİN ANADOLU POP- ROCK MÜZİK TÜRÜNE UYARLANMASININ HALKBİLİMSEL İNCELENMESİ Nafiz CAMGÖZ 2502120512 TEZ DANIŞMANI Prof. Dr. Abdulkadir EMEKSİZ İSTANBUL – 2019 ii ÖZ ANADOLU TÜRKÜLERİNİN ANADOLU POP-ROCK MÜZİK TÜRÜNE UYARLANMASININ HALKBİLİMSEL İNCELENMESİ NAFİZ CAMGÖZ Osmanlı’nın son döneminden erken Cumhuriyet dönemini de içine alan süreçte, Batı kültürüne ait olan müzik tekniğinin Türk müziği ile birleştirilmesi sonucu ortaya çıkan müziksel sentez çalışmaları, 1960’lı yıllarda ortaya çıkacak olan Anadolu pop-rock müzik türünün de habercisi niteliğindedir. Anadolu pop-rock müzik türü, geleneksel Türk halk müziğinin melodik ve ritmik motiflerinin, çalgılarının Batı müziğinin tekniğiyle ve çalgılarıyla harmanlandığı; Anadolu ve Batı müzik kültürlerinin buluştuğu sentez bir müzik türü olarak karşımıza çıkmaktadır. Bu çalışmada söz konusu müzik türü, geleneğin güncellenmesi, otantisite, kültür endüstrisi ve metinlerarasılık açısından değerlendirilmiş olup alıntılama, anıştırma, öykünme teknikleriyle ilişkilendirilerek karşılaştırmalı analizler yapılmıştır. Edinilen bilgiler ışığında Anadolu pop-rock müzik türünün, halk müziği geleneğinin çağdaş bir yorumu olduğu görülmüştür. Çünkü kültürün temel unsurları olarak gelenekler geçmişe sabitlenmiş bir olgu olmayıp sürekli değişim ve dönüşüm içindedirler. Gelenekler ve onu temsil eden otantik kültürel ürün ve pratikler, küreselleşmenin ve teknolojik -

Istanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü

İSTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ANADOLU ROCK’TA MELODİK, ARMONİK VE RİTMİK YAPI: 1965-1975 YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Burçin Bahadır GÜNER Müzikoloji ve Müzik Teorisi Anabilim Dalı Müzikoloji Programı MAYIS 2015 İSTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ANADOLU ROCK’TA MELODİK, ARMONİK VE RİTMİK YAPI: 1965-1975 YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Burçin Bahadır GÜNER 404131003 Müzikoloji ve Müzik Teorisi Anabilim Dalı Müzikoloji Programı Tez Danışmanı: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ozan Baysal Teslim Tarihi: 4 MAYIS 2015 İTÜ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’nün 404131003 numaralı Yüksek Lisans Öğrencisi Burçin Bahadır GÜNER, ilgili yönetmeliklerin belirlediği gerekli tüm şartları yerine getirdikten sonra hazırladığı “Anadolu Rock’ta Melodik, Armonik ve Ritmik Yapı: 1965-1975” başlıklı tezini aşağıda imzaları olan jüri önünde başarı ile sunmuştur. Tez Danışmanı: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ozan BAYSAL ………………….. İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Jüri Üyeleri: Prof. Songül KARAHASANOĞLU ………………...... İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Yrd. Doç. Dr. Şirin Karadeniz GÜNEY ………………….. Haliç Üniversitesi Teslim Tarihi : 4 Mayıs 2015 Savunma Tarihi : 27 Mayıs 2015 iii iv ÖNSÖZ Bu çalışma; Anadolu Rock’ın Türkiye’nin popüler müzik tarihindeki önemi gözönüne alınarak, stilistik özelliklerini müzikal metin düzeyinde açıklamak için hazırlandı. Burada amaç; Anadolu Rock’ın melodik, armonik ve ritmik yapısını açıklamak, bu stilistik yapıyı oluşturan yerel ve Batılı özellikleri de görünür kılmaktır. Çalışmada; Anadolu Rock’ın önemli üç sanatçısı Barış Manço, Cem Karaca ve Erkin Koray’ın 1965-1975 yılları arasında yayınlamış oldukları plaklardan seçilen parçaların transkripsiyonu yapılarak analiz edildi. Bu analizler sonucu ortaya çıkan özellikler hem makam müziği ile hem de Batıdaki tonal ve modal müzikal yapılar ile olan ilişkileri açısından karşılaştırıldı. Konu seçiminden itibaren tezin her aşamasındaki desteği için danışmanım Yrd. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

CEM KARACA VE BARIŞ MANÇO” ÖRNEĞİ (1960-1980) POLITICAL DISCOURSE in MUSIC and ANATOLIAN ROCK in TURKEY: the CASE of “CEM KARACA and BARIS MANCO” (1960-1980) Doç

The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies International Journal of Social Science Doi number:http://dx.doi.org/10.9761/JASSS7030 Number: 56 , p. 325-350, Spring III 2017 Yayın Süreci / Publication Process Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Article Arrival Date - Yayınlanma Tarihi / The Published Date 26.03.2017 31.05.2017 MÜZİKTE SİYASAL SÖYLEM VE TÜRKİYE’DE ANADOLU ROCK: “CEM KARACA VE BARIŞ MANÇO” ÖRNEĞİ (1960-1980) POLITICAL DISCOURSE IN MUSIC AND ANATOLIAN ROCK IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF “CEM KARACA AND BARIS MANCO” (1960-1980) Doç. Dr. Fatma Gürses Kastamonu Üniversitesi, İletişim Fakültesi Gazetecilik Bölümü Öz Rock müzik, Amerika’da ve uluslararası alanda yaygınlık kazanarak kitleye ulaşan popüler bir tür olmuştur. Dünyada, çeşitli konuların tartışıldığı, yurttaşların bu tartışmalara katıldığı, müzik akımları ve gençlik hareketinin hızla yaygınlaştığı değişim yılları olan 1960’larda bu müzik türü, siyasal söylem biçimlerinin kitleselleşmesine aracı- lık etmiştir. Dünyadaki bu değişim ve özgürlükçü hareketten etkilenen Türkiye’de ise bu dönem, yurttaşın kamusal-siyasal özne olarak algılandığı, yabancı müziklerin ülkeye gi- rişinin hızlandığı, yurttaşın kendini ifade alanı bulduğu yıllardır. 12 Eylül 1980 askeri darbesi ile Türkiye’de bu özgürlükçü ortam kesintiye uğratılmış ve siyasal sistemde kök- lü değişiklikler yapılmıştır. Bu çalışma, düzen eleştirisi getiren rock müzikten etkilene- rek Türkiye’de ortaya çıkan Anadolu rock olarak adlandırılan müzik türünün temsilcile- ri olan Cem Karaca ve Barış Manço’nun, 1960-1980 yılları arasındaki söz konusu siyasal dinamikleri şarkı sözlerinde temsil etme biçimlerini incelemeye çalışacaktır. Bu iki mü- zisyenin çalışmalarını temel alarak Türkiye’de Anadolu rock müziğinin, siyasal unsurla- rı hangi söylemsel öğelerle sabitledikleri, neleri dışlayarak veya neleri bünyesine alarak söylemi inşa ettiklerini ortaya çıkarmak çalışmanın temel hedefidir. -

Anadolu Pop/Rock'ta Toplumsal Belleğin Izini Sürmek: 1960'Lı Ve

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü İletişim Bilimleri Anabilim Dalı Kültürel Çalışmalar ve Medya Bilim Dalı ANADOLU POP/ROCK’TA TOPLUMSAL BELLEĞİN İZİNİ SÜRMEK: 1960’LI VE 1970’Lİ YILLAR Gökçen Sena DUMAN Yüksek Lisans Tezi Ankara, 2021 ANADOLU POP/ROCK’TA TOPLUMSAL BELLEĞİN İZİNİ SÜRMEK: 1960’LI VE 1970’Lİ YILLAR Gökçen Sena DUMAN Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü İletişim Bilimleri Anabilim Dalı Kültürel Çalışmalar ve Medya Bilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi Ankara, 2021 TEŞEKKÜR Teşekkürlerin en büyüğü şüphesiz devam etmekte güçlük çektiğim anlarda bana inanmaktan bir an bile vazgeçmeyen, ilerlemem için cesaretlendiren değerli tez danışmanım Doç. Dr. Gülsüm Depeli Sevinç’e. Kendisine en yoğun zamanlarında bile bana sabır, heyecan ve titizlikle yol gösterdiği için müteşekkirim. Tezimin kuramsal arka planını oluşturmaya başladığım ilk günlerden itibaren ve sonraki tüm süreçlerde bellek çalışmaları alanındaki derin bilgisini benden esirgemeyerek ufkumu açan Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Göze Orhon’a tezime sunduğu kıymetli katkılar için ne kadar teşekkür etsem az kalır. Savunma jürisinde yer almayı kabul eden değerli etnomüzikolog Doç. Dr. Evrim Hikmet Öğüt’e yapıcı yorumları ve değerli katkılarıyla tezimi zenginleştirdiği için çok teşekkür ederim. Duruşlarıyla ve ürettikleriyle akademinin gerçek anlamını ve değerini koruyan Hacettepe Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi’nin tüm değerli hocalarına da teşekkürü borç bilirim. Tez çalışmamı 2210-A Genel Yurt İçi Yüksek Lisans Burs Programı ile destekleyen TÜBİTAK Bilim İnsanı Destekleme Daire Başkanlığı (BİDEB)’na teşekkürlerimi sunarım. Saha araştırmasında yer almayı kabul ederek hayatlarını ve bellek anlatılarını bana açan, çalışmamı şekillendiren görüşmecilerimin hepsine çok teşekkür ederim. İlkokul yıllarından bugüne dek birbirimizin her anına tanık olduğumuz, İlayda, Zeynep, Mert ve Can’a bu süreçte de bana güç verdikleri için; Semiha, Şeyma ve Gamze’ye “galiba yapamayacağım” hissine kapıldığım tüm anlarda beni sabırla dinleyip keyifli sohbetleriyle sakinleşmemi sağladıkları için çok teşekkür ederim.