Archaeology and the Changing View of Custer's Last Stand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custer, George.Pdf

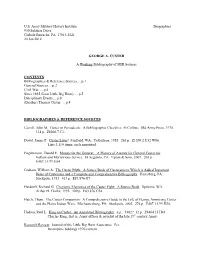

U.S. Army Military History Institute Biographies 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 20 Jan 2012 GEORGE A. CUSTER A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS Bibliographies & Reference Sources.....p.1 General Sources.....p.2 Civil War…..p.4 Since 1865 (Less Little Big Horn)…..p.5 Disciplinary Events.....p.8 (Brother) Thomas Custer…..p.8 BIBLIOGRAPHIES & REFERENCE SOURCES Carroll, John M. Custer in Periodicals: A Bibliographic Checklist. Ft Collins: Old Army Press, 1975. 134 p. Z8206.7.C3. Dowd, James P. Custer Lives! Fairfield, WA: YeGalleon, 1982. 263 p. Z1209.2.U52.W86. Lists 3,114 items, each annotated. Engebretson, Darold E. Medals for the General: A History of Awards for General Custer for Gallant and Meritorious Service. El Segundo, CA: Upton & Sons, 2007. 203 p. E467.1.C99.E54. Graham, William A. The Custer Myth: A Source Book of Custerania to Which is Added Important Items of Custerania and a Complete and Comprehensive Bibliography. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole, 1953. 413 p. E83.876.G7. Hardorff, Richard G. Cheyenne Memories of the Custer Fight: A Source Book. Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clarke, 1995. 189 p. E83.876.C54. Hatch, Thom. The Custer Companion: A Comprehensive Guide to the Life of George Armstrong Custer and the Plains Indian Wars. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2002. 274 p. E467.1.C99.H38. Hedren, Paul L. King on Custer: An Annotated Bibliography. n.p., 1982? 12 p. Z8464.35.H43. Charles King, that is, Army officer & novelist of the late 19th century Army. Research Review. Journal of the Little Big Horn Associates. Per. -

CUSTER BATTLEFIELD National Monument Montana (Now Little Bighorn Battlefield)

CUSTER BATTLEFIELD National Monument Montana (now Little Bighorn Battlefield) by Robert M. Utley National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 1 Washington, D.C. 1969 Contents a. A CUSTER PROFILE b. CUSTER'S LAST STAND 1. Campaign of 1876 2. Indian Movements 3. Plan of Action 4. March to the Little Bighorn 5. Reno Attacks 6. The Annihilation of Custer 7. Reno Besieged 8. Rescue 9. Collapse of the Sioux 10. Custer Battlefield Today 11. Campaign Maps c. APPENDIXES I. Officers of the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn II. Low Dog's Account of the Battle III. Gall's Account of the Battle IV. A Participant's Account of Major Reno's Battle d. CUSTER'S LAST CAMPAIGN: A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY e. THE ART AND THE ARTIST f. ADMINISTRATION For additional information, visit the Web site for Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument or view their Official National Park Handbook (#132): Historical Handbook Number One 1969 The publication of this handbook was made possible by a grant from the Custer Battlefield Historical and Museum Association, Inc. This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. Price lists of Park Service publications sold by the Government Printing Office may be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C. 20402. The National Park System, of which Custer Battlefield National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. -

Jewel Cave National Monument Historic Resource Study

PLACE OF PASSAGES: JEWEL CAVE NATIONAL MONUMENT HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY 2006 by Gail Evans-Hatch and Michael Evans-Hatch Evans-Hatch & Associates Published by Midwestern Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska _________________________________ i _________________________________ ii _________________________________ iii _________________________________ iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: First Residents 7 Introduction Paleo-Indian Archaic Protohistoric Europeans Rock Art Lakota Lakota Spiritual Connection to the Black Hills Chapter 2: Exploration and Gold Discovery 33 Introduction The First Europeans United States Exploration The Lure of Gold Gold Attracts Euro-Americans to Sioux Land Creation of the Great Sioux Reservation Pressure Mounts for Euro-American Entry Economic Depression Heightens Clamor for Gold Custer’s 1874 Expedition Gordon Party & Gold-Seekers Arrive in Black Hills Chapter 3: Euro-Americans Come To Stay: Indians Dispossessed 59 Introduction Prospector Felix Michaud Arrives in the Black Hills Birth of Custer and Other Mining Camps Negotiating a New Treaty with the Sioux Gold Rush Bust Social and Cultural Landscape of Custer City and County Geographic Patterns of Early Mining Settlements Roads into the Black Hills Chapter 4: Establishing Roots: Harvesting Resources 93 Introduction Milling Lumber for Homes, Mines, and Farms Farming Railroads Arrive in the Black Hills Fluctuating Cycles in Agriculture Ranching Rancher Felix Michaud Harvesting Timber Fires in the Forest Landscapes of Diversifying Uses _________________________________ v Chapter 5: Jewel Cave: Discovery and Development 117 Introduction Conservation Policies Reach the Black Hills Jewel Cave Discovered Jewel Cave Development The Legal Environment Developing Jewel Cave to Attract Visitors The Wind Cave Example Michauds’ Continued Struggle Chapter 6: Jewel Cave Under the U.S. -

Margaret Custer Calhoun

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 4-29-1896 Margaret Custer Calhoun. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indigenous, Indian, and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 2677, 54th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1896) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 54TH CONGRESS, t ROUSE OF H,EPRESENTATIVES. ) REPORT 2d Session. J l No. 2Gi"7. MARGARET CUSTER CALHOUN. JANUARY 28, 1897.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole Honse and ordered to · be printed. Mr. LOUDENSLAGER, from the Committee on Pensions, submitted the following REPORT. rro accompany s. 2954.] The Committee on Pensions, to whom was referred the bill. (S. 2954) gTanting an increase of pension to Margaret Custer·Calhoun, have con sidered the same, and respectfully report as follows: Said bill is accompanied by Senate Report No. 813, this term, and the same, fully setting forth the facts, is adopted by your committee as their report, and the bill is returned with a favorable recommendation. [Senate Report No. 813, Fifty-fourth Congress, fir.st session.) The Committee on Pensions, to whom was referred the bill (S. -

February 2014

GaryGary InterInter StateState Established Sept. 6, 1878; the only newspaper in the world solely interested in the welfare of Gary, SD and vicinity. Gary Historical Association 2014 A monthly newspaper with news of the past and present. www.experiencegarysd.com "The opinions in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Gary Historical Association.” This paper printed for you by DNB NATIONAL BANK Gary and Clear Lake SD We want to thank them for this service! Gary 605.272.5233 Clear Lake 605.874.2191 Gary, the oldest town in the county, was Dakota’s Rapid Growth. The growth of this Territory during this past year is something phe- founded in 1877 by the Winona & St. Peter Rail- nomenal . Our population has increased at the rate road Company, thought the railroad had reached of 12,000 a month, since January last. The larger that point in the fall of 1872. Gary was originally half of this increase settled in the southern half of the Territory. Post offices have been established at called State Line because of its location on the the rapid rate of 12 a month for the past 11 months. boundary line; then for a time it was called Head- Now we are a prosperous, growing and enterprising quarters, because it was the base of operations for commonwealth with a population numbering 275,00 souls; with a voting strength of 60,000; the Colonel DeGraff, the railroad contractor. advantages of Dakota over all competitors is af- An attempt was made to have it named DeGraff, firmed by over one hundred newspapers; we have but there was another town by that name on the St. -

Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery Lodge

HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY FORT LEAVENWORTH NATIONAL CEMETERY, LODGE HALS No. KS-1-A Location: 395 Biddle Boulevard, Leavenworth, Leavenworth County, Kansas. The coordinates for the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery, Lodge are 94.888227 W and 39.275444 N, and they were obtained in August 2012 with, it is assumed, NAD 1983. There is no restriction on the release of the locational data to the public. Present Owner: National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Prior to 1988, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs was known as the Veterans Administration. The Veterans Administration took over management of Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery from the U.S. Army in 1973 (Public Law 93-43). Date: 1904-05. Builder/Contractor: Unknown. Description: In 1905, the two-story, brick lodge replaced the nineteenth-century, Second Empire style stone lodge; it kept the L-shaped floor plan but raised the second floor – eliminating the mansard – and covered the whole with hipped roofs. A small, triple window dormer was cut into the roof on the southeast front elevation. The foundations of the lodge were stone and concrete and the roof was initially covered in slate. The window lintels and sills appear in early twentieth- century photographs to be made of stone, and the double-hung sash glazed with one-over-one lights. The chimneystack was constructed of brick and is visible above the roofline. There were twenty-six screens and twenty-three window shades in the building. Maintenance ledgers from the Veterans Administration for the cemetery supplied the 1905 construction date for the present lodge, and the ledgers listed a series of repairs undertaken in the 1920s to 1960s. -

Shaping America with General George A. Custer

u History Lesson u GeneralShaping Ge AmericaOrGe a. with Custer General Custer’s faithful Morgan Dandy was an unfailing member of the company. By Brenda L. tippin ne of the most colorful characters of early American Custer’s early life history is the famous General, George Custer, best A native of New Rumley, Ohio, George Armstrong Custer was remembered for The Battle of Little Big Horn, in born December 5, 1839 to Emmanuel H. Custer, a blacksmith which he and his men met a gruesome fate at the and farmer who had been widowed, and his second wife, Maria Ohands of the Sioux and other tribes gathered under Sitting Bull. A Ward, also widowed. Custer was the oldest of three brothers born strong personality, loved by many, criticized by others, controversy to this union, Nevin, Thomas, and Boston, and the youngest child still rages to this day regarding Custer and his last fight. History has was a sister, Margaret. They were plain people and hard-working often portrayed Custer as an arrogant man whose poor judgment farmers, instilling in George early on strong principles of right and was to blame for this major disaster. Many remember the horse wrong, honesty, fairness, and a keen sense of responsibility. George Comanche, a Morgan, as the lone survivor of that battle. Comanche was of a gentle nature, always full of fun, and loved practical jokes. was in fact owned by Captain Myles Keogh of Custer’s regiment. It He was called “Autie” as a child, and from his earliest life all he ever is less known that Custer himself rode several Morgans during the wanted was to be a soldier. -

At the Flood

CHAPTER 1 At the Flood igh up in his fl oating tower, Captain Grant Marsh guided the riverboat Far West toward Fort Lincoln, the home of Lieuten- ant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry. This was Marsh’s fi rst trip up the Missouri since the ice and snow had closed the river the previous fall, and Hlike any good pilot he was carefully studying how the waterway had changed. Every year, the Missouri—at almost three thousand miles the lon- gest river in the United States—reinvented itself. Swollen by spring rain and snowmelt, the Missouri wriggled and squirmed like an overloaded fi re hose, blasting away tons of bottomland and, with it, grove after grove of cottonwood trees. By May, the river was studded with partially sunken cottonwoods, their sodden root-balls planted fi rmly in the mud, their water-laved trunks angled downriver like spears. Nothing could punch a hole in the bottom of a wooden steamboat like the submerged tip of a cottonwood tree. Whereas the average life span of a seagoing vessel was twenty years, a Missouri riverboat was lucky to last fi ve. Rivers were the arteries, veins, and capillaries of the northern plains, the lifelines upon which all living things depended. Rivers determined 1 0001-470_PGI_Last_Stand.indd01-470_PGI_Last_Stand.indd 1 33/4/10/4/10 110:37:400:37:40 AMAM 2 · THE LAST STAND · the annual migration route of the buffalo herds, and it was the buf- falo that governed the seasonal movements of the Indians. -

Nineteenth-Century Army Officers'wives in British

IMPERIAL STANDARD-BEARERS: NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY OFFICERS’WIVES IN BRITISH INDIA AND THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation by VERITY GAY MCINNIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Major Subject: History IMPERIAL STANDARD-BEARERS: NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY OFFICERS’WIVES IN BRITISH INDIA AND THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation by VERITY GAY MCINNIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams J. G. Dawson III Committee Members, Sylvia Hoffert Claudia Nelson David Vaught Head of Department, David Vaught May 2012 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Imperial Standard-Bearers: Nineteenth-Century Army Officers’ Wives in British India and the American West. (May 2012) Verity Gay McInnis, B.A., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi; M.A., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. R.J.Q. Adams Dr. Joseph G. Dawson III The comparative experiences of the nineteenth-century British and American Army officer’s wives add a central dimension to studies of empire. Sharing their husbands’ sense of duty and mission, these women transferred, adopted, and adapted national values and customs, to fashion a new imperial sociability, influencing the course of empire by cutting across and restructuring gender, class, and racial borders. Stationed at isolated stations in British India and the American West, many officers’ wives experienced homesickness and disorientation. -

The 1874 Black Hills Expedition Diary of Ered W. Power

Copyright © 1998 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. "Distance Lends Enchantment to the View": The 1874 Black Hills Expedition Diary of Ered W. Power edited bv Thomas R. Buecker On 2 July 1874, a large military expedition of nearly one thousand soldiers, Indian scouts, teamsters, and attached civilians left Fort Abraham- Lincoln, near Bis- marck, Dakota Territory. During the next sixty days, this impressive cavalcade led by Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer successfully explored the Black Hills, a mysterious region that had long been the subject of rumor and spec- ulation. Despite the large number of people who marched with the 1874 Black Hills Expedition, remarkably few left personal recordings. While the official reporis and accounts of the newspaper correspondents accompanying the expedition have been widely available to researchers, few reminis- cences and diaries are known to survive. One rare exam- ple is the heretofore unpublished diary of correspondefit Fred W. Power. A welcome addition to the scant literature of the 1874 Expedition, Power's diary offers significant insights into this monumental event of Northern Great Plains history.^ 1. Standard .sources on the Ití74 Black Hilts Expedition include John M. Carroll and Lawrence A. Frost, eds.. Pnvate 'Ihmdore Ewerl's Diiiry of the fiUick Hills Expedition of 1874 (Piscataway. N.J.: CRI Btxjks, 1976); Lawrence K. Frost, ed., With Cuskr in '74. James Cai- Copyright © 1998 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. 198 South Dakota History Vol. 27, no. 4 Although goi'emtnent explorers had skirted the periph- ery of the Black Hills, none until the 1874 expedition had penetrated the region's interior First Lieutenant Gouverneur K. -

Custer Genealogies

CUSTER GENEALOGIES Compiled & Printed By Milo Custer Bloomington, Illinois 1944 Editors of New Edition John M. Carroll W. Donald Horn Guidon Press P.O. Box 44 Bryan, Texas 77801 INTRODUCTION I remember an old adage from my history teaching days which went: "You don't know who you are until you know who you were, and you don't know where you're going until you know where you've been." Its value as an historical statement is unchallenged; to understand any character in history it is necessary to know all about his family's genealogy. This has never been more true than for General George Armstrong Custer. The General has been treated variously in the media as a true folk hero, a self-serving egoist, a military genius, a military fool, an ambitious man, a man satisfied with his sta tion in life and his accomplishments, and a man who was either a womanizer or a faithful husband. Whichever attitude prevailed was the one which was held by the viewer. The General may have been all of those; he may have been none of these. Yet, the inconsistency of public opinion proved one fact: General Custer was a public figure who was destined to become one of the most controversial men in American history. The fact that he had enemies and detractors is incon trovertible. No successful man can achieve what he did in such a short period of time without having created some enemies. That can also account for a bit of egotism in the man. It has been said that a person can determine the pace and degree of fame he has achieved by turning around and counting the number of people shaking their fists at him. -

The Limit of Endurance Has Been Reached: the 7Th Us Cavalry

THE LIMIT OF ENDURANCE HAS BEEN REACHED: THE 7TH U.S. CAVALRY REGIMENT, RACIAL TERROR AND RECONSTRUCTION, 1871-1876 A Dissertation by THOMAS GLENN NESTER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Major Subject: History The Limit of Endurance Has Been Reached: The 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, Racial Terror and Reconstruction, 1871-1876 Copyright 2010 Thomas Glenn Nester THE LIMIT OF ENDURANCE HAS BEEN REACHED: THE 7TH U.S. CAVALRY REGIMENT, RACIAL TERROR AND RECONSTRUCTION, 1871-1876 A Dissertation by THOMAS GLENN NESTER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson III Committee Members, Walter Kamphoefner Albert Broussard Henry C. Schmidt William Bedford Clark Head of Department, Walter Buenger May 2010 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT The Limit of Endurance Has Been Reached: The 7th U.S. Cavalry, Racial Terror, and Reconstruction, 1871-76. (May 2010) Thomas Glenn Nester, B.A., Susquehanna University; M.A., Temple University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson III The 7th Cavalry Regiment participated in Reconstruction during two of its most critical phases. Companies from the regiment were deployed to South Carolina, from 1871-73, to conduct the federal government’s campaign to eradicate the Ku Klux Klan and to Louisiana, from 1874-76, in an effort to protect the legally-elected state government against White League depredations.