Prisons of North Korea1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tumen Triangle Documentation Project

THE TUMEN TRIANGLE DOCUMENTATION PROJECT SOURCING THE CHINESE-NORTH KOREAN BORDER Edited by CHRISTOPHER GREEN Issue Two February 2014 ABOUT SINO-NK Founded in December 2011 by a group of young academics committed to the study of Northeast Asia, Sino-NK focuses on the borderland world that lies somewhere between Pyongyang and Beijing. Using multiple languages and an array of disciplinary methodologies, Sino-NK provides a steady stream of China-DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/North Korea) documentation and analysis covering the culture, history, economies and foreign relations of these complex states. Work published on Sino-NK has been cited in such standard journalistic outlets as The Economist, International Herald Tribune, and Wall Street Journal, and our analysts have been featured in a range of other publications. Ultimately, Sino-NK seeks to function as a bridge between the ubiquitous North Korea media discourse and a more specialized world, that of the academic and think tank debates that swirl around the DPRK and its immense neighbor. SINO-NK STAFF Editor-in-Chief ADAM CATHCART Co-Editor CHRISTOPHER GREEN Managing Editor STEVEN DENNEY Assistant Editors DARCIE DRAUDT MORGAN POTTS Coordinator ROGER CAVAZOS Director of Research ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS Outreach Coordinator SHERRI TER MOLEN Research Coordinator SABINE VAN AMEIJDEN Media Coordinator MYCAL FORD Additional translations by Robert Lauler Designed by Darcie Draudt Copyright © Sino-NK 2014 SINO-NK PUBLICATIONS TTP Documentation Project ISSUE 1 April 2013 Document Dossiers DOSSIER NO. 1 Adam Cathcart, ed. “China and the North Korean Succession,” January 16, 2012. 78p. DOSSIER NO. 2 Adam Cathcart and Charles Kraus, “China’s ‘Measure of Reserve’ Toward Succession: Sino-North Korean Relations, 1983-1985,” February 2012. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

Full Case Study

National Park Service National Park Service U. S. Department of the Interior Civic Engagement www.nps.gov/civic/ Civic Engagement and the Gulag Museum at Perm-36, Russia Through communication with former prisoners and guards and an international dialogue with other "sites of conscience," The Gulag Museum at Perm-36, Russia, is building all its programs on a foundation of civic engagement. In December 1999, National Park Service (NPS) Northeast Regional Director Marie Rust became a founding member of the International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience. At the Coalition’s first formal meeting, Ms. Rust met Dr. Victor Shmyrov, Director of the Gulag Museum at Perm-36 in Russia, another founding institution of the Coalition. Dr. Shmyrov’s museum preserves and interprets a gulag camp built under Joseph Stalin in 1946 near the city of Perm in the village of Kutschino, Russia. Known as Perm-36, the camp served initially as a regular timber production labor camp. Later, the camp became a particularly isolated and severe facility for high government officials. In 1972, Perm-36 became the primary facility in the country for persons charged with political crimes. Many of the Soviet Union’s most prominent dissidents, including Vladimir Bukovsky, Sergei Kovalev and Anatoly Marchenko, served their sentences there. It was only during the Soviet government’s period of “openness” of Glasnost, under President Mikael Gorbachev, that the camp was finally closed in 1987. Although there were over 12,000 forced labor camps in the former Soviet Union, Perm-36 is the last surviving example from the system. -

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

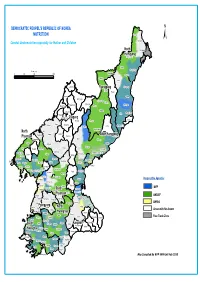

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

The Historical Experience of Labor: Archaeological Contributions To

4 Barbara L. Voss (芭芭拉‧沃斯) Pacific Railroad, complained about the scarcity of white labor in California. Crocker proposed that Chinese laborers would be hardworking The Historical Experience and reliable; both he and Stanford had ample of Labor: Archaeological prior experience hiring Chinese immigrants to work in their homes and on previous business Contributions to Interdisciplinary ventures (Howard 1962:227; Williams 1988:96). Research on Chinese Railroad construction superintendent J. H. Stro- Railroad Workers bridge balked but relented when faced with rumors of labor organizing among Irish immi- 劳工的历史经验:考古学对于中 grants. As Crocker’s testimony to the Pacific 国铁路工人之跨学科研究的贡献 Railway Commission later recounted: “Finally he [Strobridge] took in fifty Chinamen, and a ABSTRACT while after that he took in fifty more. Then, they did so well that he took fifty more, and he Since the 1960s, archaeologists have studied the work camps got more and more until we finally got all we of Chinese immigrant and Chinese American laborers who could use, until at one time I think we had ten built the railroads of the American West. The artifacts, sites, or twelve thousand” (Clark 1931:214; Griswold and landscapes provide a rich source of empirical informa- 1962:109−111; Howard 1962:227−228; Chiu tion about the historical experiences of Chinese railroad 1967:46; Kraus 1969a:43; Saxton 1971:60−66; workers. Especially in light of the rarity of documents Mayer and Vose 1975:28; Tsai 1986; Williams authored by the workers themselves, archaeology can provide 1988:96−97; Ambrose 2000:149−152; I. Chang direct evidence of habitation, culinary practices, health care, social relations, and economic networks. -

Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps

forced labour in North Korean Prison Camps Norma Kang Muico Anti-Slavery International 2007 Acknowledgments We would like to thank the many courageous North Koreans who have agreed to be interviewed for this report and shared with us their often difficult experiences. We would also like to thank the following individuals and organisations for their input and assistance: Amnesty International, Baspia, Choi Soon-ho, Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights (NKHR), Good Friends, Heo Yejin, Human Rights Watch, Hwang Sun-young, International Crisis Group (ICG), Mike Kaye, Kim Soo-am, Kim Tae-jin, Kim Yoon-jung, Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), Ministry of Unification (MOU), National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), Save the Children UK, Tim Peters and Sarangbang. The Rufford Maurice Laing Foundation kindly funded the research and production of this report as well as connected activities to prompt its recommendations. Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Background 2 2. Border Crossing 3 3. Surviving in China 4 Employment 4 Rural Brides 5 4. Forcible Repatriation 6 Police Raids 6 Deportation 8 5. Punishment upon Return 8 Kukga Bowibu (National Security Agency or NSA) 9 Yeshim (Preliminary Examination) 10 Living Conditions 13 The Waiting Game 13 6. Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps 14 Nodong Danryundae (Labour Training Camp) 14 Forced Labour 14 Pregnant Prisoners 17 Re-education 17 Living Conditions 17 Food 18 Medical Care 18 Do Jipkyulso (Provincial Detention Centre) 19 Forced Labour 19 Living Conditions 21 Inmin Boansung (People's Safety Agency or PSA) 21 Formal Trials 21 Informal Sentencing 22 Released without Sentence 22 Arbitrary Decisions 22 Kyohwaso (Re-education Camp) 24 Forced Labour 24 Food 24 Medical Care 25 7. -

Emergency Appeal Final Report Democratic People’S Republic of Korea (DPRK) / North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Appeal Final Report Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) / North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal N°: MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of Issue: 26 March 2018 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date: 31 December 2017 Host National Society: Red Cross Society of Democratic Operation budget: CHF 5,037,707 People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RCS) Number of people affected: 600,000 people Number of people assisted: 110,000 people (27,500 households) N° of National Societies involved in the operation: 19 National Societies: Austrian Red Cross, British Red Cross, Bulgarian Red Cross, China Red Cross, Hong Kong and Macau branches, Czech Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Finnish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, New Zealand Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Red Crescent Society of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Red Cross of Monaco, Spanish Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross, the Canadian Red Cross Society, the Netherlands Red Cross, the Republic of Korea National Red Cross. The Governments of Austria, Denmark, Finland, Malaysia, Netherlands, Switzerland and Thailand, the European Commission - DG ECHO, and Czech private donors, the Korea NGO Council for Cooperation with North Korea, Movement of One Korea, National YWCA of Korea and the WHO Voluntary Emergency Relief Fund have contributed financially to the operation. N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), ICRC, UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units Summary: This report gives an account of the humanitarian situation and the response carried out by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) during the period between 12 September 2016 and 31 December 2017, as per revised Emergency Operation Appeal (EPOA) with the support of International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) to meet the needs of floods affected families of North Hamgyong Province in DPRK. -

Searchable PDF Format

- Yangdok Hot Spring Resort - Popular Ceramics Exhibition House - World of Prodigies Silver Ornament A gift presented to President Kim Il Sung by Kaleda Zia, Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh in April 1992 Monthly Journal (766) C O N T E N T S 3 Yangdok Hot Spring Resort 10 Korean Nation’s History of Using Hot Spring 11 Architecture for the People 12 Fruit of Enthusiasm 13 Offensive for Frontal Breakthrough and Increased Production and Economy 14 Old Home at Mangyongdae 17 The Secret Camp on Mt. Paektu 21 Understanding of the People Monthly journal Korea Today is posted on the Internet site www.korean-books.com.kp in English, Russian and Chinese. 1 22 Seventy-fi ve Years of WPK (4) Revolutionary Martyrs Cemetery Tells 23 Relying on Domestic Resources 24 Consumer Changes to Producer 26 Popular Ceramics Exhibition House 28 Nano Cloth Developers Front Cover: Yangdok 29 Target of Developers Hot Spring Resort in the morning 30 World of Prodigies Photo by Kim Kum Sok 32 Record-breaking Achievement in 2019 36 True story I’ll Remain a Winner (7) 38 Promising Sheep Breeding Base 40 Pioneer of Complex Hand-foot Refl ex Therapy 41 Disabled Table Tennis Player 42 National Dog under Good Care 43 Story of Headmaster 44 Glimpse of Japan’s Plunder of Korean Cultural Heritage Back Cover: Moran Hill in spring 46 National Intangible Cultural Heritage (41) Photo by Kim Ji Ye Sijungho Mud Therapy 47 Poetess Ho Ran Sol Hon 13502 ㄱ – 208057 48 Mt Kuwol (3) Edited by Kim Myong Hak Address: Sochon-dong, Sosong District, Pyongyang, DPRK E-mail: fl [email protected] © The Foreign Language Magazines 2020 2 YYangdokangdok HHotot SSpringpring RResortesort No. -

DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal n° MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of issue: 20 September 2016 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Marlene Fiedler Pak Un Suk Disaster Risk Management Delegate Emergency Relief Coordinator IFRC DPRK Country Office DPRK Red Cross Society Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date (timeframe): 31 August 2017 (12 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 15,199,723 DREF allocation: CHF 506,810 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 600,000 people Direct: 28,000 people (7,000 families); Indirect: more than 163,000 people in Hoeryong City, Musan County and Yonsa County Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster From August 29th to August 31st heavy rainfall occurred in North Hamgyong Province, DPRK – in some areas more than 300 mm of rain were reported in just two days, causing the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the province. Within a particularly intense time period of four hours in the night between 30 and 31 August 2016, the waters of the river Tumen rose between six and 12 metres, causing an immediate threat to the lives of people in nearby villages. -

WATER SUPPLY and HABITAT PROJECTS in the DPRK ICRC Mission in the Democratic People’S Republic of Korea

PROJECT BRIEF WATER SUPPLY AND HABITAT PROJECTS IN THE DPRK ICRC Mission in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea PROGRAMME OVERVIEW Since 2013, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been working on water supply in peri-urban areas. Launched in different years, the four ongo- ing projects mainly involve construction with locally available materials and are in different phases of completion. Once finished, they will benefit about 123,750 inhabitants, ensuring they have sustainable access to clean water. Renovations at two local hospitals and two Physical Rehabilitation Centres will enable the public facilities to run more effectively and provide people with up-to-standard infra- structure and services. The Ministry of Urban Management PARTNERS The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Red Cross Society The International Committee of the Red Cross Water supply to peri-urban communities Jongpyong Eup Town water-supply system Kaechon City water-supply system Location Jongpyong, South Hamgyong Province Location Kaechon, South Pyongan Province Population targeted 43,000 Population targeted 59,200 Starting year 2018 Starting year 2019 Completion May 2020 Completion May 2020 Constructed in the 1970s, the existing water-supply system is Kaechon relies on a pumped water-supply system set up in unable to cover the current needs due to an increase in popu- the 1970s. Over the years, the quality of source well has wors- lation and reduction and deterioration of the water source. ened with the pumps too old to function fully, electricity for Households receive water in shifts and residents without piped pumping has been limited and distribution pipes are broken water in their houses draw it from hand-dug wells, which are and have developed leaks. -

Tenth Congress of the Youth League Held Glorious History of the Korean Children’S Union Scenery of the Taedong River, Yesterday and Today

Tenth Congress of the Youth League Held Glorious History of the Korean Children’s Union Scenery of the Taedong River, Yesterday and Today DEMOCRATIC PEOPLe’S REPUBLIC OF JUCHE 110 KOREA (2021) 6 (786) CONTENTS Qingtian Stone Sculpture Special Report 2 ∥ General Secretary Kim Jong Un Saw Plain Sailing Performance of Art Groups of KPA Officers’ Wives 4 ∥ General Secretary Kim Jong Un Had a Photo Session with Participants in the Tenth Congress of the Youth League 6 ∥ Tenth Congress of the Youth League Held Commemoration 12 12 ∥ Glorious History of the Korean Children’s Union 22 ∥ Scenes of June Etched in the History of World Diplomacy ∙ Promoting the DPRK-China Friendship to a Higher Level ∙ DPRK-China Friendship That Will Last Forever on the Road of Socialism ∙ Epoch-making Meeting Heralding a New Chapter of DPRK-US Relations 36 Korea Today 36 ∥ Scenery of the Taedong River, Yesterday and Today 42 ∥ June 1 International Children’s Day 44 ∥ Happy Children 52 ∥ Loud Whistles of School Train 56 ∥ 13 000 Hectares of Tideland Reclaimed 60 ∥ After a Day’s Work 66 ∥ Acrobatic Performance Full of Laughter and Optimism 44 Folklore & Culture 72 ∥ People Performing Traditional Mask Dance 78 ∥ Sustaining the Tradition of Manufacturing National Musical Instruments Sports 86 ∥ Pyongyang International Football School Gift presented to General Secretary Kim Jong Un by the then Nature State Councillor and Minister of Public Security of the 92 ∥ Mt Myohyang 72 People’s Republic of China (February 14, 2011) Editors: Sin Jae Chol, Kim Jong Chol, So Chol Nam, FRONT COVER: On a trip for nature study Kim Kyu Song, Sung Ryong Photo: Pang Un Sim, Hong Kwang Nam 1 2021. -

Christmas in North Korea

Christmas in North Korea Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi With contributions from Talha Jilani Asad Alamgir Guven Uzun Suleman Khan Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Adnan I. Qureshi All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5054-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5054-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors .............................................................................................. x Preface ...................................................................................................... xi 1. The Journey to North Korea ............................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction to the Korean Peninsula 1.2. Tour to North Korea 1.3. Introduction to The Pyongyang Times 1.4. Arrival at Pyongyang International Airport 2. Brief History ........................................................................................ 32 2.1. The ‘Three Kingdom’ and ‘Later Three Kingdom’ periods 2.2. Goryeo kingdom 2.3. Joseon kingdom 2.4. Japanese occupation 2.5. Complete Japanese control 2.6. Post-Japanese occupation 2.7. The Korean War 3. Contemporary North Korea .............................................................. 58 3.1. The first communist dynasty and its challenges 3.2. The changing face of the communist economic structure 3.3. Nuclear power 3.4. Rocket technology 3.5. Life amidst sanctions 3.6. Mineral resources 3.7. Mutual defense treaties 3.8. Governmental structure of North Korea 3.9.