Uromastyx Dispar Heyden, 1827

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA CHORDATA 16SCCZO3 Dr. R. JENNI & Dr. R. DHANAPAL DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY M. R. GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE MANNARGUDI CONTENTS CHORDATA COURSE CODE: 16SCCZO3 Block and Unit title Block I (Primitive chordates) 1 Origin of chordates: Introduction and charterers of chordates. Classification of chordates up to order level. 2 Hemichordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Balanoglossus and its affinities. 3 Urochordata: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Herdmania and its affinities. 4 Cephalochordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Branchiostoma (Amphioxus) and its affinities. 5 Cyclostomata (Agnatha) General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Petromyzon and its affinities. Block II (Lower chordates) 6 Fishes: General characters and classification up to order level. Types of scales and fins of fishes, Scoliodon as type study, migration and parental care in fishes. 7 Amphibians: General characters and classification up to order level, Rana tigrina as type study, parental care, neoteny and paedogenesis. 8 Reptilia: General characters and classification up to order level, extinct reptiles. Uromastix as type study. Identification of poisonous and non-poisonous snakes and biting mechanism of snakes. 9 Aves: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Columba (Pigeon) and Characters of Archaeopteryx. Flight adaptations & bird migration. 10 Mammalia: General characters and classification up -

Biomechanical Assessment of Evolutionary Changes in the Lepidosaurian Skull

Biomechanical assessment of evolutionary changes in the lepidosaurian skull Mehran Moazena,1, Neil Curtisa, Paul O’Higginsb, Susan E. Evansc, and Michael J. Fagana aDepartment of Engineering, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, United Kingdom; bThe Hull York Medical School, University of York, York YO10 5DD, United Kingdom; and cResearch Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom Edited by R. McNeill Alexander, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 24, 2009 (received for review December 23, 2008) The lepidosaurian skull has long been of interest to functional mor- a synovial joint with the pterygoid, the base resting in a pit (fossa phologists and evolutionary biologists. Patterns of bone loss and columellae) on the dorsolateral pterygoid surface. Thus, the gain, particularly in relation to bars and fenestrae, have led to a question at issue in relation to the lepidosaurian lower temporal variety of hypotheses concerning skull use and kinesis. Of these, one bar is not the functional advantage of its loss (13), but rather of of the most enduring relates to the absence of the lower temporal bar its gain in some rhynchocephalians and, very rarely, in lizards in squamates and the acquisition of streptostyly. We performed a (12, 14). This, in turn, raises questions as to the selective series of computer modeling studies on the skull of Uromastyx advantages of the different lepidosaurian skull morphologies. hardwickii, an akinetic herbivorous lizard. Multibody dynamic anal- Morphological changes in the lepidosaurian skull have been ysis (MDA) was conducted to predict the forces acting on the skull, the subject of theoretical and experimental studies (6, 8, 9, and the results were transferred to a finite element analysis (FEA) to 15–19) that aimed to understand the underlying selective crite- estimate the pattern of stress distribution. -

Report on Species/Country Combinations Selected for Review by the Animals Committee Following Cop16 CITES Project No

AC29 Doc. 13.2 Annex 1 UNEP-WCMC technical report Report on species/country combinations selected for review by the Animals Committee following CoP16 CITES Project No. A-498 AC29 Doc. 13.2 Annex 1 Report on species/country combinations selected for review by the Animals Committee following CoP16 Prepared for CITES Secretariat Published May 2017 Citation UNEP-WCMC. 2017. Report on species/country combinations selected for review by the Animals Committee following CoP16. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many experts who provided valuable data and opinions in the compilation of this report. Copyright CITES Secretariat, 2017 The UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity assessment centre of UN Environment, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. The Centre has been in operation for over 30 years, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. Reuse of any figures is subject to permission from the original rights holders. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from UN Environment. Applications for permission, with a statement of purpose and extent of reproduction, should be sent to the Director, UNEP-WCMC, 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UN Environment, contributory organisations or editors. The designations employed and the presentations of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UN Environment or contributory organisations, editors or publishers concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries or the designation of its name, frontiers or boundaries. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Uromastyx by Catherine Love, DVM Updated 2021

Uromastyx By Catherine Love, DVM Updated 2021 Natural History Uromastyx, also known as spiny-tailed or dabb lizards, are a genus of herbivorous, diurnal lizards found in northern Africa, the Middle East, and northwest India. This genus of lizard is in the agamid family, the same family as bearded dragons and frilled lizards. There are 13 recognized uromastyx species, but not all are commonly kept in captivity in the United States. U. aegyptia (Egyptian), U. ornatus (ornate), U. geyri (saharan), U. nigriventris (Moroccan), U. dispar (Mali), and U. ocellata (ocellated) are some of the most commonly kept. Uros dig burrows or spend time in rocky crevices to protect themselves from the elements in their desert habitats. These lizards naturally inhabit rocky terrain in very arid climates and are often found basking in direct sunlight. Characteristics and Behavior Uros tend to be quite docile and tolerant of handling, with some owners even claiming their lizard seeks out interaction. These lizards don’t tend to bite, but can be skittish if time is not taken to tame them. Ornate uromastyx have been noted to be bolder, while Egyptian and Moroccan uromastyx may be more shy. As with other members of the agamid family, uromastyx do not possess tail autotomy (they can’t drop their tails). Uros are heat loving, mid-day basking lizards that thrive in arid environments. Uros have a gland near their nose that excretes salt, which may cause a white build-up near their nostrils (keepers affectionately refer to this build-up as “snalt”). They are fairly hardy and handleable lizards that make good pets for intermediate keepers. -

Gross Trade in Appendix II FAUNA (Direct Trade Only), 1999-2010 (For

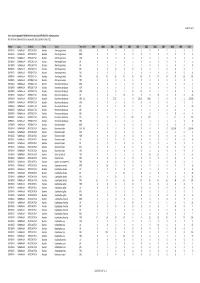

AC25 Inf. 5 (1) Gross trade in Appendix II FAUNA (direct trade only), 1999‐2010 (for selection process) N.B. Data from 2009 and 2010 are incomplete. Data extracted 1 April 2011 Phylum Class TaxOrder Family Taxon Term Unit 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BOD 0 00001000102 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BON 0 00080000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia HOR 0 00000110406 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia LIV 0 00060000006 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKI 1 11311000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKP 0 00000010001 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKU 2 052101000011 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia TRO 15 42 49 43 46 46 27 27 14 37 26 372 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Antilope cervicapra TRO 0 00000020002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae BOD 0 00100001002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOP 0 00200000002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOR 0 0010100120216 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae LIV 0 0 5 14 0 0 0 30 0 0 0 49 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA KIL 0 5 27.22 0 0 272.16 1000 00001304.38 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA 0 00000000101 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae -

Uromastyx Ocellata Lichtenstein, 1823

AC22 Doc. 10.2 Annex 6e Uromastyx ocellata Lichtenstein, 1823 FAMILY: Agamidae COMMON NAMES: Eyed Dabb Lizard, Ocellated Mastigure, Ocellated Uromastyx, Eyed Spiny-tailed Lizard, Smooth-eared (English); Fouette-queue Ocellé (French); Lagarto de Cola Espinosa Ocelado (Spanish) GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS: Currently being assessed by IUCN Global Reptile Assessment. SIGNIFICANT TRADE REVIEW FOR: Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan Range States selected for review Range Exports* Urgent, Comments States (1994-2003) possible or least concern Djibouti 0 Least concern No trade reported Egypt 4 528 Least concern Export of species banned since 1992. No exports recorded since 1995. Eritrea 0 Least concern No trade reported Ethiopia 477 Least concern Ethiopia’s CITES Authorities confirm its presence. Trade levels low. Export quotas in place based on population surveys. Somalia 0 Least concern No trade reported Sudan 11,702 Least concern Main exporter; low levels of trade (<3000 yr-1). No systematic population monitoring in place to determine non-detriment. SUMMARY Uromastyx ocellata, commonly known in the pet trade as the Ocellated Spiny-tailed Lizard, is recorded from Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan. Ethiopia’s CITES Scientific Authority also report that the species is found in that country. It is found in wadis in rocky mountainous desert with acacia trees. U. ocellata is reportedly fairly common in some range States, although regarded as declining in some areas. If it occurs at population densities comparable to those of other Uromastyx species, its population is likely to number at minimum several hundred thousand individuals. Reported exports of U. ocellata during the period 1994-2003 were mainly from Sudan (11,702) and Egypt (4,528) with Ethiopia also exporting specimens. -

The New Mode of Thought of Vertebrates' Evolution

etics & E en vo g lu t lo i y o h n a P r f y Journal of Phylogenetics & Kupriyanova and Ryskov, J Phylogen Evolution Biol 2014, 2:2 o B l i a o n l r o DOI: 10.4172/2329-9002.1000129 u g o y J Evolutionary Biology ISSN: 2329-9002 Short Communication Open Access The New Mode of Thought of Vertebrates’ Evolution Kupriyanova NS* and Ryskov AP The Institute of Gene Biology RAS, 34/5, Vavilov Str. Moscow, Russia Abstract Molecular phylogeny of the reptiles does not accept the basal split of squamates into Iguania and Scleroglossa that is in conflict with morphological evidence. The classical phylogeny of living reptiles places turtles at the base of the tree. Analyses of mitochondrial DNA and nuclear genes join crocodilians with turtles and places squamates at the base of the tree. Alignment of the reptiles’ ITS2s with the ITS2 of chordates has shown a high extent of their similarity in ancient conservative regions with Cephalochordate Branchiostoma floridae, and a less extent of similarity with two Tunicata, Saussurea tunicate, and Rinodina tunicate. We have performed also an alignment of ITS2 segments between the two break points coming into play in 5.8S rRNA maturation of Branchiostoma floridaein pairs with orthologs from different vertebrates where it was possible. A similarity for most taxons fluctuates between about 50 and 70%. This molecular analysis coupled with analysis of phylogenetic trees constructed on a basis of manual alignment, allows us to hypothesize that primitive chordates being the nearest relatives of simplest vertebrates represent the real base of the vertebrate phylogenetic tree. -

Amphibians and Reptiles of the Mediterranean Basin

Chapter 9 Amphibians and Reptiles of the Mediterranean Basin Kerim Çiçek and Oğzukan Cumhuriyet Kerim Çiçek and Oğzukan Cumhuriyet Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70357 Abstract The Mediterranean basin is one of the most geologically, biologically, and culturally complex region and the only case of a large sea surrounded by three continents. The chapter is focused on a diversity of Mediterranean amphibians and reptiles, discussing major threats to the species and its conservation status. There are 117 amphibians, of which 80 (68%) are endemic and 398 reptiles, of which 216 (54%) are endemic distributed throughout the Basin. While the species diversity increases in the north and west for amphibians, the reptile diversity increases from north to south and from west to east direction. Amphibians are almost twice as threatened (29%) as reptiles (14%). Habitat loss and degradation, pollution, invasive/alien species, unsustainable use, and persecution are major threats to the species. The important conservation actions should be directed to sustainable management measures and legal protection of endangered species and their habitats, all for the future of Mediterranean biodiversity. Keywords: amphibians, conservation, Mediterranean basin, reptiles, threatened species 1. Introduction The Mediterranean basin is one of the most geologically, biologically, and culturally complex region and the only case of a large sea surrounded by Europe, Asia and Africa. The Basin was shaped by the collision of the northward-moving African-Arabian continental plate with the Eurasian continental plate which occurred on a wide range of scales and time in the course of the past 250 mya [1]. -

Study of Halal and Haram Reptil (Dhab "Uromastyx Aegyptia

Study of Halal and Haram Reptil (Dhab "Uromastyx aegyptia", Biawak "Varanus salvator", Klarap "Draco volans") in Interconnection-Integration Perspective in Animal Systematics Practicum Sutriyono Integrated Laboratory of Science and Technology State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta - Indonesia Correspondency email: [email protected] Abstract Indonesia as a country with the largest Muslim population in the world, halal and haram being important and interesting issues, and will have more value if being related to science and religion. The research aimed to study halal and haram of reptiles by tracing manuscripts of Islam and science, combining, analyzing, and drawing conclusions with species Uromastyx aegyptia (Desert lizard), Varanus salvator (Javan lizard), and Draco volan (Klarap). The results showed that Dhab (Uromastyx aegyptia) (Desert lizard) is halal, based on the hadith narrated by Muslim no. 3608, hadith narrated by Al-Bukhari no. 1538, 1539. Uromastyx aegyptia are herbivorous animals although sometimes they eat insects. Javanese lizards (Varanus salvator) in Arabic called waral, wild and fanged animals is haram for including carnivores, based on hadith narrated by Muslim no. 1932, 1933, 1934, hadith narrated by Al-Bukhari no. 5530. Klarap (Draco volans)/cleret gombel/gliding lizard is possibly halal because no law against it. Draco volans is an insectivorous, not a wild or fanged animal, but it can be haram if disgusting. Draco volans has the same category taxon as Uromastyx aegyptia at the family taxon. Keywords: Halal-haram, Reptile, Interconnection, Integration, Animal Systematics. Introduction Indonesia as a country with the largest Muslim population in the world, halal and haram are an important and interesting issues and will have more value if being related to science and religion. -

Evolutionary History of Spiny- Tailed Lizards (Agamidae: Uromastyx) From

Received: 6 July 2017 | Accepted: 4 November 2017 DOI: 10.1111/zsc.12266 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evolutionary history of spiny- tailed lizards (Agamidae: Uromastyx) from the Saharo- Arabian region Karin Tamar1 | Margarita Metallinou1† | Thomas Wilms2 | Andreas Schmitz3 | Pierre-André Crochet4 | Philippe Geniez5 | Salvador Carranza1 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC- Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Barcelona, The subfamily Uromastycinae within the Agamidae is comprised of 18 species: three Spain within the genus Saara and 15 within Uromastyx. Uromastyx is distributed in the 2Allwetterzoo Münster, Münster, Germany desert areas of North Africa and across the Arabian Peninsula towards Iran. The 3Department of Herpetology & systematics of this genus has been previously revised, although incomplete taxo- Ichthyology, Natural History Museum of nomic sampling or weakly supported topologies resulted in inconclusive relation- Geneva (MHNG), Geneva, Switzerland ships. Biogeographic assessments of Uromastycinae mostly agree on the direction of 4CNRS-UMR 5175, Centre d’Écologie Fonctionnelle et Évolutive (CEFE), dispersal from Asia to Africa, although the timeframe of the cladogenesis events has Montpellier, France never been fully explored. In this study, we analysed 129 Uromastyx specimens from 5 EPHE, CNRS, UM, SupAgro, IRD, across the entire distribution range of the genus. We included all but one of the rec- INRA, UMR 5175 Centre d’Écologie Fonctionnelle et Évolutive (CEFE), PSL ognized taxa of the genus and sequenced them for three mitochondrial and three Research University, Montpellier, France nuclear markers. This enabled us to obtain a comprehensive multilocus time- calibrated phylogeny of the genus, using the concatenated data and species trees. We Correspondence Karin Tamar, Institute of Evolutionary also applied coalescent- based species delimitation methods, phylogenetic network Biology (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu Fabra), analyses and model- testing approaches to biogeographic inferences. -

Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco: a Taxonomic Update and Standard Arabic Names

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 1-14 (2021) (published online on 08 January 2021) Checklist of amphibians and reptiles of Morocco: A taxonomic update and standard Arabic names Abdellah Bouazza1,*, El Hassan El Mouden2, and Abdeslam Rihane3,4 Abstract. Morocco has one of the highest levels of biodiversity and endemism in the Western Palaearctic, which is mainly attributable to the country’s complex topographic and climatic patterns that favoured allopatric speciation. Taxonomic studies of Moroccan amphibians and reptiles have increased noticeably during the last few decades, including the recognition of new species and the revision of other taxa. In this study, we provide a taxonomically updated checklist and notes on nomenclatural changes based on studies published before April 2020. The updated checklist includes 130 extant species (i.e., 14 amphibians and 116 reptiles, including six sea turtles), increasing considerably the number of species compared to previous recent assessments. Arabic names of the species are also provided as a response to the demands of many Moroccan naturalists. Keywords. North Africa, Morocco, Herpetofauna, Species list, Nomenclature Introduction mya) led to a major faunal exchange (e.g., Blain et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2017) and the climatic events that Morocco has one of the most varied herpetofauna occurred since Miocene and during Plio-Pleistocene in the Western Palearctic and the highest diversities (i.e., shift from tropical to arid environments) promoted of endemism and European relict species among allopatric speciation (e.g., Escoriza et al., 2006; Salvi North African reptiles (Bons and Geniez, 1996; et al., 2018). Pleguezuelos et al., 2010; del Mármol et al., 2019).