Introduction the “AUTONOMY” of BLACK RADICALISM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View the Sankofa African Heritage Book List

A B C D E F COPY- TITLE AUTHORS ED PUBLISHER(S) COVER ANNOTATION 1 RIGHT African Origins of the Majors Yosef Ben jochannan 1970- All Western religions had 2 Western Religions Yosef Ben Jochannan Publishing 360pp Paper their beginnings in Africa The Encyclopedia of the 1999- African and African American 3 AFRICANA Kwame-Gates, editors Basic Civitas Books 2045pp Cloth Experience 2002- 4 Africans Americans David Boyle Barrons 127pp Cloth Coming to America Today, we live in a changed Al on America, The Right Reverend Kingsenton Publishing 2002- America, changed by people 5 Al Sharpton Karen Hunter Group 280pp Cloth who risk their own lives. 2009- What Should Black People Do 6 America I Am Legends Foreword : Tavis Smiley Smiley books 180pp Paper Now? Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, 2008- and Forgotten Founders who 7 America's Hidden History Kenneth C. Davis Smithsonian Books 265pp Cloth shaped a Nation Ancient Egypt, The Light of the 1990- A work of reclamation and 8 World,Vol 1-B and vol.2--A Gerald Massey ECA Associates 750pp Paper restitution in twelve volumes The teaching and prophetic wisdom of the Seven 1999- Hermetic laws of Ancient 9 Ancient Future Wayne B. Chandler Black Classic Press 246pp Paper Egypt 2009- The U.S. Commission on Civil 10 And Justice For All Mary Frances Berry Knopf Publishers 425pp Cloth Rights 1995- Everyday liife ritual and court 11 Art and Craft in Africa Laure Meyer Terrial Publishers, Montreal 208pp Paper art B.B. King and Dick 2005- Collection of treasures of 12 B.B.King- Treasures Waterman Bulfinch Press 160pp cloth B.B. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 9 Article 15 2009 Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement Melissa Seifert Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Seifert, Melissa (2009) "Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Seifert: Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in t Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement By: Melissa Seifert The origins of the Black Power Movement can be traced back to the civil rights movement’s sit-ins and freedom rides of the late nineteen fifties which conveyed a new racial consciousness within the black community. The initial forms of popular protest led by Martin Luther King Jr. were generally non-violent. However, by the mid-1960s many blacks were becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow pace and limited extent of progressive change. -

Walter Rodney and Black Power: Jamaican Intelligence and Us Diplomacy*

ISSN 1554-3897 AFRICAN JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY & JUSTICE STUDIES: AJCJS; Volume 1, No. 2, November 2005 WALTER RODNEY AND BLACK POWER: JAMAICAN INTELLIGENCE AND US DIPLOMACY* Michael O. West Binghamton University On October 15, 1968 the government of Jamaica barred Walter Rodney from returning to the island. A lecturer at the Jamaica (Mona) campus of the University of the West Indies (UWI), Rodney had been out of the country attending a black power conference in Canada. The Guyanese-born Rodney was no stranger to Jamaica: he had graduated from UWI in 1963, returning there as a member of the faculty at the beginning of 1968, after doing graduate studies in England and working briefly in Tanzania. Rodney’s second stint in Jamaica lasted all of nine months, but it was a tumultuous and amazing nine months. It is a measure of the mark he made, within and without the university, that the decision to ban him sparked major disturbances, culminating in a rising in the capital city of Kingston. Official US documents, until now untapped, shed new light on the “Rodney affair,” as the event was soon dubbed. These novel sources reveal, in detail, the surveillance of Rodney and his activities by the Jamaican intelligence services, not just in the months before he was banned but also while he was a student at UWI. The US evidence also sheds light on the inner workings of the Jamaican government and why it acted against Rodney at the particular time that it did. Lastly, the documents offer a window onto US efforts to track black power in Jamaica (and elsewhere in WALTER RODNEY AND BLACK POWER: JAMAICAN INTELLIGENCE AND US DIPLOMACY Michael O. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

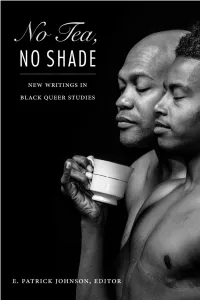

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

'The Only Position for Women in SNCC Is Prone'

‘The Only Position for Women in SNCC is Prone’ 29 ‘The Only Position for Women in SNCC is Prone’: Stokely Carmichael and the Perceived Patriarchy of Civil Rights Organisations in America 1 Sabina Peck Second Year Undergraduate, 1 University of New South Wales There is the danger in our culture that because a person is called upon to give public statements and is acclaimed by the establishment, such a person gets to the point of believing that he is the movement ... There are those, some of the young people [of SNCC] especially, who have said to me that if I had not been a woman I would have been well known in certain places, and perhaps held certain kinds of positions. – Ella Baker, 19702 Until relatively recently, historiography concerning the Civil Rights movement and its organisations has been fairly devoid of the study of the participation of women, focusing instead on certain charismatic, notably black male individuals such as Martin Luther King Jnr., Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X.3 Steven Lawson, for example, has traced the evolution of 1 Note the following abbreviations are used throughout the article: CORE- Congress of Racial Equality MFDP – Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party NAACP – National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People SCLC – Southern Christian Leadership Conference SNCC – Student Non-violent Co-ordinating Committee 2 Ella Baker, Developing Community Leadership, Taped interview with Gerda Lerner (December 1970) paragraphs 15 and 14, respectively. 3 Joan C. Browning explores the extent to which women’s activities have been glossed over in Civil Rights Historiography in her article, ‘Invisible Revolutionaries: White Women in Civil Rights Historiography’ Journal of Women’s History, Vol. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1 . Similar attempts to link poetry to immediate political occasions have been made by Mark van Wienen in Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War and by John Marsh’s anthology You Work Tomorrow . See also Nancy Berke’s Women Poets on the Left and John Lowney’s History, Memory, and the Literary Left: Modern American Poetry, 1935–1968 . 2 . Jos é E. Lim ó n discusses the “mixture of poetry and politics” that informed the Chicano movements of the 1960s and 1970s (81). On Vietnam antiwar poetry, see Bibby. There are, of course, countless studies of individual authors that trace their relationships to politics and social movements. I incorporate the relevant studies throughout the chapters. 3 . In analogy to Wallerstein’s model, the literary world has been conceptualized as a largely autonomous cultural space constituted by power struggles between centers, semi-peripheries, and peripheries, most prominently by Franco Moretti and Pascale Casanova (cf. Moretti; Casanova). But since Wallerstein insists that the world-system is concerned with world-economies (global capitalism) and world-empires (nation-states aiming for geopolitical dominance), systems, that is, which cut across cultural and institutional zones, it seems more plausible to posit the modern world-system as the historical horizon of textual production and interpretation. One of the first uses of world-systems analysis for a concep- tualization of postmodernity and postmodern art was Fredric Jameson’s essay “Culture and Finance Capital” ( Cultural Turn 136–61). 4 . Ramazani remains elusive about the extraliterary reference of these poets’ imagination. -

The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The Enemy Within: The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures Olivier Maheo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/471 DOI: 10.4000/angles.471 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Olivier Maheo, « The Enemy Within: The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/471 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.471 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The Enemy Within: The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures 1 The Enemy Within: The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures Olivier Maheo Introduction: A Liberal Agenda 1 The 20th century could be described as the one that gave birth to a new “civilization of the image.” (Gusdorf 1960: 11). By using images in its nation-building efforts, the United States has been a forerunner through what François Brunet called “Amérique- image”, a huge picture-book in which photographs of the Civil Rights Movement have a dedicated slot at a time when television was becoming a mass media (Brunet & Kempf 2001). The best-known pictures of the Civil Rights Movement have thus become places of memory, iconic images testifying to the ultimate triumph of democracy. 2 If, according to W.E.B. -

Curriculum Vitae SHARON HARLEY

Curriculum Vitae SHARON HARLEY Home Address: Office Address: 3101 New Mexico Avenue African American Studies Department Unit 234 1117 Taliaferro Hall Washington, DC 20016 University of Maryland (202) 607-4077 College Park, MD 20742 (301) 405-1158 phone / (301) 314-9932 fax E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION May 1981 Ph.D., United States History Minor: Latin American/Caribbean History (honors, comprehensive examination) Department of History, Howard University, Washington, DC Dissertation Title: "Black Women in the District of Columbia, 1890-1920: Their Social, Economic and Institutional Activities" August 1971 M.A.T., Education (Emphasis on the Social Sciences) Antioch College (Washington campus), Yellow Springs, Ohio May 1970 B.A., History St. Mary-of-the-Woods College, St. Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana Summer 1977 Special Training: Quantitative Methods for Historians Newberry Library/University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1988-Present Associate Professor and Chair (1993-2010) of African American Studies/History and Affiliate Faculty Member, Women's Studies and American Studies, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland (UMD). Undergraduate Courses Taught: Research Methodologies in African American Studies; Constructions of Manhood and Womanhood in Black Communities; Gender, Racial Identity and Nationality in African Diaspora Communities; Women and Work (cross-listed with Sociology); Black Culture in the United States; Directed Readings: Black Racialized Body; Black Women in the United States (part of the Women's Studies Curriculum); Seminar in Methodology and Theory of Afro-American Studies (interdisciplinary and team-taught); Introduction to Afro-American Studies; Directed and Classic Readings in Afro-American Studies; History of Thought in the African American Tradition (seminar); and Diversity in Oneness: The Making of African-American Communities (two semester, team-taught honors course) Graduate Courses Taught: Black Culture in the U.S.