'The Expressive Organ Within Us:' Ether, Ethereality, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Alternately Known As 1313; Originally Releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, Numerous Intervening Reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform

UNIVERS ZERO UNIVERS ZERO CUNEIFORM 2008 REISSUE W BONUS TRACKS & REMASTER (alternately known as 1313; originally releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, numerous intervening reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform) Cuneiform 2008 album features: Michel Berckmans [bassoon], Daniel Denis [percussion], Marcel Dufrane [violin], Christian Genet [bass], Patrick Hanappier [violin, viola, pocket cello], Emmanuel Nicaise [harmonium, spinet], Roger Trigaux [guitar], and Guy Segers [bass, vocal, noise effects] “ALBUM OF THE WEEK...Released in 1977, it was astonishing then: today, it sounds like the hidden source for every one of today's avant-garde rock bands. Chillingly beautiful, driven by the bassoon and cello more than the guitar and synth, each instrumental is both pastoral and burgeoning with terrible life. … This is edgy beyond belief. …Each piece magnificently refuses to deviate from its mood, its tense, thrilling, growling, restrained focus... The whole is like the rare, delicious bits of great film soundtrack that create menace and energy out of nowhere. … Univers Zero are a revelation …” – Sean O., Organ, #274, September 18th, 2008 “UZ's debut remains both benchmark and landmark. Reissued numerous times over the years…this definitive version finally presents this unprecedented music the way it was meant to be heard, clarifying how—emerging out of nowhere with little history to precede it— UZ has been so vital in changing the way chamber music is perceived. UZ's music was an antecedent for the kind of instrumental and stylistic interspersion considered normal today by groups including Bang on a Can and Alarm Will Sound. Henry Cow's complex, abstruse writing meets Bartok, Stravinsky, Messiaen and Ligeti, but with hints of early music, especially in UZ's use of spinet and harmonium. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele IT’S EASY WITH THE LEE OSKAR HARMONICA SYSTEM... SpiceSpice upup youryour songssongs withwith thethe soulfulsoulful soundsound ofof thethe harmonicaharmonica alongalong withwith youryour GuitarGuitar oror UkuleleUkulele playing!playing! Information all in one place! Online Video Guides Scan or visit: leeoskarquickguide.com ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. - All Rights Reserved Major Diatonic Key labeled in 1st Position (Straight Harp) Available in 14 keys: Low F, G, Ab, A, Bb, B, C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#, High G Key of C MAJOR DIATONIC BLOW DRAW The Major Diatonic harmonica uses a standard Blues tuning and can be played in the 1st Position (Folk & Country) or the 2 nd Position (Blues, Rock/Pop Country). 1 st Position: Folk & Country Most Folk and Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the blow (exhale) chord. This is called 1 st Position, or straight harp, playing. Begin by strumming your guitar / ukulele: C F G7 C F G7 With your C Major Diatonic harmonica Key of C MIDRANGE in its holder, starting from blow (exhale), BLOW try to pick out a melody in the midrange of the harmonica. DRAW Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do C Major scale played in 1st Position C D E F G A B C on a C Major Diatonic harmonica. 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. All Rights Reserved 2nd Position: Blues, Rock/Pop, Country Most Blues, Rock, and modern Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the draw (inhale) chord. -

THE IDEA of TIMBRE in the AGE of HAYDN a Dissertation

THE IDEA OF TIMBRE IN THE AGE OF HAYDN A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Emily I. Dolan August 2006 © 2006 Emily I. Dolan THE IDEA OF TIMBRE IN THE AGE OF HAYDN Emily I. Dolan, Ph. D. Cornell University 2006 At the end of the 18th century, instrumental music, formerly subordinate to vocal music and shackled to the doctrine of imitation, dramatically emerged as a new and powerful form or art, capable of expression. Many scholars today turn to developments in aesthetic philosophy—the birth of German Idealism, “absolute music,” or Kantian formalism—to explain the changing perception of instrumental music. Such explanations, though they illuminate important aspects of contemporary philosophy, ultimately blind us to fascinating developments in musical practice. This dissertation locates the heart of this transformation not in philosophical aesthetics, but in the musical medium itself, specifically focusing on the birth of the concept of timbre and the ensuing transformations to musical discourse. Tracing the concept of timbre from its birth in the writings of Rousseau through its crystallization in the early 19th century with the emergence of “orchestra machines” and a widespread obsession with effect, the dissertation explores the impact of the new focus on the musical medium in different registers of musical culture. The project examines the use of the metaphor of color borrowed from painting and Newtonian science, the philosophical attitudes towards transience and sensation in the writings of Kant and Herder, ideas of composition and orchestration in music treatises, and composers’ new uses for the orchestra through close analysis of Haydn’s style of orchestration in the 1790s. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

GMW Spring 2000

Glass Music World Nominees for GMI Officers The GMI Nominating Committee has received the following Slate of Officers to be elected at the GMI Business Meeting, April 28, 2000 PRESIDENT: Carlton Davenport has been Commissioner while in Franklin (doing a glass music enthusiast since the late 80s. extensive research on Ben Franklin) and Dear GMI membership: He is currently retired from Digital has been involved with glass music since Equipment Company and has been study- 1982. Liz has served as GMI Membership Festival time is just around the corner! We have ing jazz piano in the central Massachusetts Chairman and editor of Glass Music World, an exciting schedule of events (updated in this area. He and his wife June have been and is currently coordinating her second issue) to enjoy. In addition to all the wonderful involved in ballroom dancing for the past GMI Glass Music Festival. Although she is musicians already slated to perform, Clemens 12 years. Carlton has a B.A. in Psychology active in several music and history organiza- Hoffinger – an exceptional glass harpist from from Bowdoin College, ME, a B.S. in tions in her community, her sons and her Zoest, Germany – will now be joining us, and Electrical Engineering from Newark growing family are her first priority. recently Jamey Turner has enthusiastically College of Engineering, NJ, and an M.B.A. agreed to perform on Thursday, April 27th. from Boston University. His working SECRETARY: Roy E. Goodman has been career was in Engineering Management for affiliated with the American Philosophical Our registrations are building up, but we still 36 years, with expertise in Quality Society in Philadelphia, where he is current- need to hear from you right away if you are Management. -

International News at a Glance —

International News THE NOME NUGGET v uni ■ u—■ Published Monday. Wednesday and Friday by the At A Glance — NOME PUBLISHING %CO. NOME. ALASKA ' TAFT- HARTL1V d'untinued from Page One) Telephone: Main 125 P. O. Box 6it* IM* dtp .i’tment s policy was seen aim- $1.50 PER MONTH SI6.00 A YEAR ed nght at Sweden which has been W. A. Boucher Owner-Publisher cp >rted urgnig Norway and Den- Emily Boucher .Local Editor mark to keep out of the North At- fantic alliance. Entered as second class matter October 14. 1943, at the postoffice military at Nome, Alaska, under the Act of March 3, 1379. Monday, January 17, 1949 Nome, Alaska, Monday, January 17, 1949 Chinese nationalists massed 50,000 men on a 300-mile front BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, BORN JANUARY 17, 1706 today in an apparently hopeless effore to save menaced Benjamin Franklin, whose is observed to- anking, birthday by communist troops in double was “the most acute and broadminded day, January 17, that strength. thinker of his in the estimation of the day,” Encyclopae- The government’s forces already dia Britannica. have abandoned Pengpu and evac- The first edition of the Britannica, published in 1768 uated towns in the path of an ex- pected communist into the when Franklin was 62, devoted many pages to his dis- sweep Yangtze river had coveries in the field of And 181 valley. Pengpu electricity. today, years been an anchor of the govern- later, Franklin is still praised for his creative mind, his ment’s Hawai river defense line. practical good sense and his humanitarianism. -

Paddock Wood to Hawkhurst Branch Line, Tunbridge Wells, Kent

Paddock Wood to Hawkhurst Branch Line, Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Historic Environment Desk-Based Assessment (with particular reference to the links with local hop growing and picking) Volume 1 Report Project No: 33013 January 2016 Paddock Wood to Hawkhurst Branch Line, Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Historic Environment Desk-based Assessment (with particular reference to the links with local hop growing and picking) On Behalf of: Hop Pickers Line Heritage Group C/o Town Hall Royal Tunbridge Wells Kent TN1 1RS National Grid Reference: TQ 67870 45222 to TQ 7582 3229 AOC Project No: 33013 Prepared by: Matt Parker Wooding Illustration by: Lesley Davidson Approved by: Melissa Melikian Date of Assessment: January 2016 This document has been prepared in accordance with AOC standard operating procedures Report Author: Matt Parker Wooding Date: January 2016 Report Approved by: Melissa Melikian Date: January 2016 Enquiries to: AOC Archaeology Group Unit 7 St Margarets Business Centre Moor Mead Road Twickenham TW1 1JS Tel. 020 8843 7380 Fax. 020 8892 0549 PADDOCK WOOD TO HAWKHURST BRANCH LINE, TUNBRIDGE WELLS, KENT: HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT CONTENTS Volume 1 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................................................................ IV LIST OF PLATES ............................................................................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................................................. -

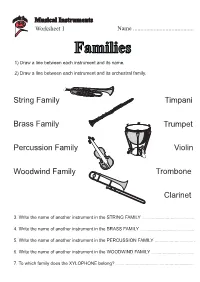

Families 2) Draw a Line Between Each Instrument and Its Orchestral Family

Musical Instruments Worksheet 1 Name ......................................... 1) Draw a line between each instrument and its name.Families 2) Draw a line between each instrument and its orchestral family. String Family Timpani Brass Family Trumpet Percussion Family Violin Woodwind Family Trombone Clarinet 3. Write the name of another instrument in the STRING FAMILY .......................................... 4. Write the name of another instrument in the BRASS FAMILY ........................................... 5. Write the name of another instrument in the PERCUSSION FAMILY ................................ 6. Write the name of another instrument in the WOODWIND FAMILY .................................. 7. To which family does the XYLOPHONE belong? ............................................................... Musical Instruments Worksheet 3 Name ......................................... Multiple Choice (Tick the correct family) String String String Oboe Brass Double Brass Bass Brass Woodwind bass Woodwind drum Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cymbals Brass Bassoon Brass Trumpet Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String French Brass Cello Brass Clarinet Brass horn Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cor Brass Trombone Brass Saxophone Brass Anglais Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Viola Brass Castanets Brass Euphonium Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion -

The Harmonica and Irish Traditional Music by Don Meade

The Harmonica and Irish Traditional Music by Don Meade ! 2012 Donald J. Meade All rights reserved 550 Grand Street, Apt. H6F New York, NY 10002 USA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 WHAT KIND OF HARMONICA? 4 TECHNICAL TIPS 13 MAJOR, MINOR, MODAL 16 ORNAMENTATION 18 CUSTOMIZING AND MAINTAINING CHROMATIC HARMONICAS 21 Appendix A: IRISH HARMONICA DISCOGRAPHY 26 Apendix B: MODE AND POSITION CHART 32 Appendix C: HARMONICA HISTORY 33 2 INTRODUCTION influenced by the way in which song airs The name “harmonica” has over the years and dance tunes are played on instruments been applied to a variety of musical with a longer history in the country, have instruments, the earliest of which was developed their own distinctive techniques probably an array of musical glasses and styles. created by Ben Franklin in 1761. The 19th- century German-speakers who invented the Instrumental technique is not really the key mouth-blown free-reed instrument now to playing Irish traditional music. Anyone known as the harmonica originally called it a who has ever heard a classical violinist Mundharmonika (“mouth harmonica”) to stiffly bow through a fiddle tune will distinguish it from the Handharmonika or understand that technical competence accordion. English speakers have since cannot substitute for an understanding of called it many things, including the mouth traditional style. That understanding can organ, mouth harp, French harp, French only be acquired by listening to and fiddle, harpoon, gob iron, tin sandwich and emulating good traditional players. If you Mississippi saxophone. “Mouth organ” is the want to play Irish music, you should listen to most common name in Ireland, where as much of it as possible. -

New Glass Review 10.Pdf

'New Glass Review 10J iGl eview 10 . The Corning Museum of Glass NewG lass Review 10 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1989 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, dal3 sie the 1988 calendar year. innerhalb des Kalenderjahres 1988 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare des New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 (607) 937-5371 All rights reserved, 1989 Alle Rechtevorbehalten, 1989 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Dusseldorf FRG Gedruckt in Dusseldorf, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-119-X ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der KongreB-Bucherei 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstler und Objekte 10 Bibliography/Bibliographie 30 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Verzeichnis der Eigennamen und Orte 53 er Wunsch zu verallgemeinern scheint fast ebenso stark ausgepragt Jury Statements Dzu sein wie der Wunsch sich fortzupflanzen. Jeder mochte wissen, welchen Weg zeitgenossisches Glas geht, wie es in der Kunstwelt bewer- tet wird und welche Stile, Techniken und Lander maBgeblich oder im Ruckgang begriffen sind. Jedesmal, wenn ich mich hinsetze und einen Jurybericht fur New Glass Review schreibe (dies ist mein 13.), winden he desire to generalize must be almost as strong as the desire to und krummen sich meine Gedanken, um aus den tausend und mehr Dias, Tprocreate.