Making Great Lakes Connections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics Lake Michigan is a dynamic deepwater oligotrophic ecosystem that supports a diverse mix of native and non-native species. Although the watershed, wetlands, and tributaries that drain into the open waters are comprised of a wide variety of habitat types critical to supporting its diverse biological community this section will focus on the open water component of this system. Watershed, wetland, and tributaries issues will be addressed in the Northeastern Morainal Natural Division section. Species diversity, as well as their abundance and distribution, are influenced by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors that define a variety of open water habitat types. Key abiotic factors are depth, temperature, currents, and substrate. Biotic activities, such as increased water clarity associated with zebra mussel filtering activity, also are critical components. Nearshore areas support a diverse fish fauna in which yellow perch, rockbass and smallmouth bass are the more commonly found species in Illinois waters. Largemouth bass, rockbass, and yellow perch are commonly found within boat harbors. A predator-prey complex consisting of five salmonid species and primarily alewives populate the pelagic zone while bloater chubs, sculpin species, and burbot populate the deepwater benthic zone. Challenges Invasive species, substrate loss, and changes in current flow patterns are factors that affect open water habitat. Construction of revetments, groins, and landfills has significantly altered the Illinois shoreline resulting in an immeasurable loss of spawning and nursery habitat. Sea lampreys and alewives were significant factors leading to the demise of lake trout and other native species by the early 1960s. -

Physical Limnology of Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron

PHYSICAL LIMNOLOGY OF SAGINAW BAY, LAKE HURON ALFRED M. BEETON U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Ann Arbor, Michigan STANFORD H. SMITH U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Ann Arbor, Michigan and FRANK H. HOOPER Institute for Fisheries Research Michigan Department of Conservation Ann Arbor, Michigan GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION 1451 GREEN ROAD ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN SEPTEMBER, 1967 PHYSICAL LIMNOLOGY OF SAGINAW BAY, LAKE HURON1 Alfred M. Beeton, 2 Stanford H. Smith, and Frank F. Hooper3 ABSTRACT Water temperature and the distribution of various chemicals measured during surveys from June 7 to October 30, 1956, reflect a highly variable and rapidly changing circulation in Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron. The circula- tion is influenced strongly by local winds and by the stronger circulation of Lake Huron which frequently causes injections of lake water to the inner extremity of the bay. The circulation patterns determined at six times during 1956 reflect the general characteristics of a marine estuary of the northern hemisphere. The prevailing circulation was counterclockwise; the higher concentrations of solutes from the Saginaw River tended to flow and enter Lake Huron along the south shore; water from Lake Huron entered the northeast section of the bay and had a dominant influence on the water along the north shore of the bay. The concentrations of major ions varied little with depth, but a decrease from the inner bay toward Lake Huron reflected the dilution of Saginaw River water as it moved out of the bay. Concentrations in the outer bay were not much greater than in Lake Huronproper. -

Lake Ontario a Voice!

Statue Stories Chicago: The Public Writing Competition Give Lake Ontario a voice! Behind the Art Institute of Chicago, is the Fountain of the Great Lakes. Within the famous fountain is the wistful figure of Lake Ontario. She sits apart from her sister lakes, gazing into the distance with arms outstretched. But what does she have to say for herself? Write a Monologue! Monologos means “speaking alone” in Greek, but we all know that people who speak without thinking about their listener can be very dull indeed. Your challenge is to find a ‘voice’ for your statue and to write an engaging monologue in 350 words. Get under your statue’s skin! Look closely and develop a sense of empathy with the sculpture and imagine how it would feel. How does Lake Ontario feel about her sister lakes? Invite your listener to feel with you: create shifts in tempo and emotion, use different tenses, figures of speech and anecdotes, sensory details and even sound effects. Finding your sculpture’s voice? Write in the first person and adopt the persona of your character: What kind of vocabulary will you use - your own or that of another era/dialect? Your words will be spoken so read them aloud: use their rhythm and your sentence structure to convey emotion and urgency. Read great monologues for inspiration, for example Hamlet’s Alas Poor Yorick, or watch film monologues, like Morgan Freeman’s in The Shawshank Redemption. How will you keep people listening? Structure your monologue! How will you introduce yourself? With a greeting, a warning, a question, an order, a riddle? Grab and hold your listener’s attention from your very first line. -

Of the American Falls at Niagara 1I I Preservation and Enhancement of the American Falls at Niagara

of the American Falls at Niagara 1I I Preservation and Enhancement of the American Falls at Niagara Property of t';e Internztio~al J5it-t; Cr?rn:n es-un DO NOT' RECda'dg Appendix G - Environmental Considerations Final Report to the International Joint Commission by the American Falls International Board June -1974 PRESERVATION AND ENHANCEMENT OF AMERICAN FALLS APPENDIX. G .ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph Page CHAPTER G 1 .INTRODUCTION G1 CHAPTER G2 .ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING . NIAGARA RESERVATION AND SURROUNDING REGION GENERAL DESCRIPTION ............................................................... PHYSICAL ELEMENTS ..................................................................... GENERAL .................................................................................... STRATIGRAPHY ......................................................................... SOILS ............................................................................................ WATER QUALITY ........................................................................ CLIMATE INVENTORY ................................................................... CLIMATE ....................................................................................... AIR QUALITY .............................................................................. BIOLOGICAL ELEMENTS ................................................................ TERRESTRIAL VEGETATION ..................................................... TERRESTRIAL WILDLIFE ......................................................... -

Lake Huron Scuba Diving

SOUTHERN LAKE ASSESSMENT SOUTHERN RECREATION PROFILE LAKE Scuba Diving: OPPORTUNITIES FOR LAKE HURON ASSESSMENT FINGER LAKES SCUBA LAKES FINGER The southern Lake Huron coast is a fantastic setting for outdoor exploration. Promoting the region’s natural assets can help build vibrant communities and support local economies. This series of fact sheets profiles different outdoor recreation activities that could appeal to residents and visitors of Michigan’s Thumb. We hope this information will help guide regional planning, business develop- ment and marketing efforts throughout the region. Here we focus on scuba diving – providing details on what is involved in the sport, who participates, and what is unique about diving in Lake Huron. WHY DIVE IN LAKE HURON? With wildlife, shipwrecks, clear water and nearshore dives, the waters of southern Lake Huron create a unique environment for scuba divers. Underwater life abounds, including colorful sunfish and unusual species like the longnose gar. The area offers a large collection of shipwrecks, and is home to two of Michigan’s 12 underwater preserves. Many of the wrecks are in close proximity to each other and are easily accessed by charter or private boat. The fresh water of Lake Huron helps to preserve the wrecks better than saltwater, and the lake’s clear water offers excellent visibility – often up to 50 feet! With many shipwrecks at different depths, the area offers dives for recreational as well as technical divers. How Popular is Scuba Diving? Who Scuba Dives? n Scuba diving in New York’s Great Lakes region stimulated more than $108 In 2010, 2.7 million Americans went scuba A snapshot of U.S. -

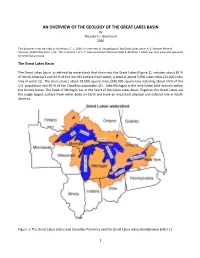

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

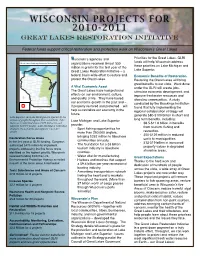

GLRI Fact Sheet

WISCONSIN PROJECTS FOR 2010-2011 Great Lakes Restoration Initiative Federal funds support critical restoration and protection work on Wisconsinʼs Great Lakes Wisconsinʼs agencies and Priorities for the Great Lakes. GLRI funds will help Wisconsin address Great Lakes Drainage Basins in Wisconsin organizations received almost $30 these priorities on Lake Michigan and Lake Superior million in grants for the first year of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative – a Lake Superior. federal basin-wide effort to restore and Economic Benefits of Restoration protect the Great Lakes. Restoring the Great Lakes will bring great benefits to our state. Work done A Vital Economic Asset under the GLRI will create jobs, The Great Lakes have had profound stimulate economic development, and Lake effects on our environment, culture, Michigan improve freshwater resources and ! and quality of life. They have fueled shoreline communities. A study our economic growth in the past and – conducted by the Brookings Institution if properly restored and protected – will Map Scale: found that fully implementing the 1 inch = 39.46 miles help us revitalize our economy in the regional collaboration strategy will future. generate $80-$100 billion in short and Lake Superior and Lake Michigan are affected by the actions of people throughout their watersheds. Lake Lake Michigan and Lake Superior long term benefits, including: Superior’s watershed drains 1,975,902 acres and provide: • $6.5-$11.8 billion in benefits supports 123,000 people. Lake Michigan’s watershed from tourism, fishing and drains 9,105,558 acres and supports 2,352,417 • Sport fishing opportunities for people. more than 250,000 anglers, recreation. -

Landforms & Bodies of Water

Name Date Landforms & Bodies of Water - Vocab Cards hill noun a raised area of land smaller than a mountain. We rode our bikes up and down the grassy hill. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: island noun a piece of land surrounded by water on all sides. Marissa's family took a vacation on an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: 1 lake noun a large body of fresh or salt water that has land all around it. The lake freezes in the wintertime and we go ice skating on it. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: landform noun any of the earth's physical features, such as a hill or valley, that have been formed by natural forces of movement or erosion. I love canyons and plains, but glaciers are my favorite landform. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: 2 mountain noun a land mass with great height and steep sides. It is much higher than a hill. Someday I'm going to hike and climb that tall, steep mountain. Synonyms: peak Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: ocean noun a part of the large body of salt water that covers most of the earth's surface. -

Great Lakes/Big Rivers Fisheries Operational Plan Accomplishment

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Fisheries Operational Plan Accomplishment Report for Fiscal Year 2004 March 2003 Region 3 - Great Lakes/Big Rivers Partnerships and Accountability Aquatic Habitat Conservation and Management Workforce Management Aquatic Species Conservation and Aquatic Invasive Species Management Cooperation with Native Public Use Leadership in Science Americans and Technology To view monthly issues of “Fish Lines”, see our Regional website at: (http://www.fws.gov/midwest/Fisheries/) 2 Fisheries Accomplishment Report - FY2004 Great Lakes - Big Rivers Region Message from the Assistant Regional Director for Fisheries The Fisheries Program in Region 3 (Great Lakes – Big Rivers) is committed to the conservation of our diverse aquatic resources and the maintenance of healthy, sustainable populations of fish that can be enjoyed by millions of recreational anglers. To that end, we are working with the States, Tribes, other Federal agencies and our many partners in the private sector to identify, prioritize and focus our efforts in a manner that is most complementary to their efforts, consistent with the mission of our agency, and within the funding resources available. At the very heart of our efforts is the desire to be transparent and accountable and, to that end, we present this Region 3 Annual Fisheries Accomplishment Report for Fiscal Year 2004. This report captures our commitments from the Region 3 Fisheries Program Operational Plan, Fiscal Years 2004 & 2005. This document cannot possibly capture the myriad of activities that are carried out by any one station in any one year, by all of the dedicated employees in the Fisheries Program, but, hopefully, it provides a clear indication of where our energy is focused. -

Humber River Watershed Plan Pathways to a Healthy Humber June 2008

HUMBER RIVER WATERSHED PLAN PAThwAYS TO A HEALTHY HUMBER JUNE 2008 Prepared by: Toronto and Region Conservation © Toronto and Region Conservation 2008 ISBN: 978-0-9811107-1-4 www.trca.on.ca 5 Shoreham Drive, Toronto, Ontario M3N 1S4 phone: 416-661-6600 fax: 416-661-6898 HUMBER RIVER WATERSHED PLAN PATHWAYS TO A HEALTHY HUMBER JUNE 2008 Prepared by: Toronto and Region Conservation i Humber River Watershed Plan, 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Humber River Watershed Plan—Pathways to a Healthy Humber—was written by Suzanne Barrett, edited by Dean Young and represents the combined effort of many participants. Appreciation and thanks are extended to Toronto and Region Conservation staff and consultants (listed in Appendix F) for their technical support and input, to government partners for their financial support and input, and to Humber Watershed Alliance members for their advice and input. INCORPORATED 1850 Humber River Watershed Plan, 2008 ii HUMBER RIVER WATERSHED PLAN PATHWAYS TO A HEALTHY HUMBER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Humber River watershed is an extraordinary resource. It spans 903 square kilometres, from the headwaters on the Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine down through fertile clay plains to the marshes and river mouth on Lake Ontario. The watershed provides many benefits to the people who live in it. It is a source of drinking water drawn from wells or from Lake Ontario. Unpaved land absorbs water from rain and snowfall to replenish groundwater and streams and reduce the negative impacts of flooding and erosion. Healthy aquatic and terrestrial habitats support diverse communities of plants and animals. Agricultural lands provide local sources of food and green spaces provide recreation opportunities. -

Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources Underlying the US Portions of The

The eight continuous AUs (and associated basins) are as follows: Table 2. Summary of mean values of Great Lakes oil and National Assessment of Oil and Gas Fact Sheet 1. Pennsylvanian Saginaw Coal Bed Gas AU (Michigan Basin), gas resource allocations by lake. 2. [Devonian] Northwestern Ohio Shale AU (Appalachian Basin), [Compiled from table 1, which contains the full range of statistical 3. [Devonian] Marcellus Shale AU (Appalachian Basin), values] Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources Underlying the 4. Devonian Antrim Continuous Gas AU (Michigan Basin), 5. Devonian Antrim Continuous Oil AU (Michigan Basin), Total undiscovered resources U.S. Portions of the Great Lakes, 2005 6. [Silurian] Clinton-Medina Transitional AU (Appalachian Basin), Oil Gas Natural gas 7. [Ordovician] Utica Shale Gas AU (Appalachian Basin), and (million (trillion liquids 8. Ordovician Collingwood Shale Gas AU (Michigan Basin). barrels), cubic feet), (million barrels), Of these eight continuous AUs, only the following four AUs were Lake mean mean mean Lake bathymetry (meters) 300 - 400 assessed quantitatively: [Silurian] Clinton-Medina Transitional AU, Devo- he U.S. Geological Survey recently completed Lake Erie 46.10 3.013 40.68 T 200 - 300 nian Antrim Continuous Gas AU, [Devonian] Marcellus Shale AU, and Lake Superior allocations of oil and gas resources underlying the U.S. por- 100 - 200 Allocation [Devonian] Northwestern Ohio Shale AU. The other four continuous AUs Lake Huron 141.02 0.797 42.49 area tions of the Great Lakes. These allocations were developed 0 - 100 lacked sufficient data to assess quantitatively. Lake Michigan 124.59 1.308 37.40 from the oil and gas assessments of the U.S. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion.