Aspects of the Indo-European Aorist and Imperfect Re-Evaluating the Evidence of the R̥gveda and Homer and Its Implications for PIE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

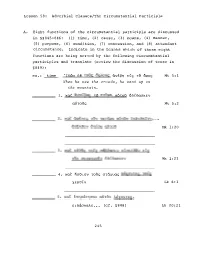

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Aktionsart and Aspect in Qiang

The 2005 International Course and Conference on RRG, Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 26-30 AKTIONSART AND ASPECT IN QIANG Huang Chenglong Institute of Ethnology & Anthropology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Qiang language reflects a basic Aktionsart dichotomy in the classification of stative and active verbs, the form of verbs directly reflects the elements of the lexical decomposition. Generally, State or activity is the basic form of the verb, which becomes an achievement or accomplishment when it takes a directional prefix, and becomes a causative achievement or causative accomplishment when it takes the causative suffix. It shows that grammatical aspect and Aktionsart seem to play much of a systematic role. Semantically, on the one hand, there is a clear-cut boundary between states and activities, but morphologically, however, there is no distinction between them. Both of them take the same marking to encode lexical aspect (Aktionsart), and grammatical aspect does not entirely correspond with lexical aspect. 1.0. Introduction The Ronghong variety of Qiang is spoken in Yadu Township (雅都鄉), Mao County (茂縣), Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (阿壩藏族羌族自治州), Sichuan Province (四川省), China. It has more than 3,000 speakers. The Ronghong variety of Qiang belongs to the Yadu subdialect (雅都土語) of the Northern dialect of Qiang (羌語北部方言). It is mutually intelligible with other subdialects within the Northern dialect, but mutually unintelligible with other subdialects within the Southern dialect. In this paper we use Aktionsart and lexical decomposition, as developed by Van Valin and LaPolla (1997, Ch. 3 and Ch. 4), to discuss lexical aspect, grammatical aspect and the relationship between them in Qiang. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

A Discourse Analysis of the Periphrastic Imperfect In

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE PERIPHRASTIC IMPERFECT IN THE GREEK NEW TESTAMENT WRITINGS OF LUKE by CARL E. JOHNSON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2010 Copyright © by Carl Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to express my sincere appreciation to each member of my committee whose helpful criticism has made this project possible. I am indebted to Don Burquest for his incredible attention to detail and his invaluable encouragement at certain critical junctures along the way; to my chair Jerold A. Edmondson who challenged me to maintain a linguistic focus and helped me frame this work within the broader linguistic perspective; and to Dr. Chiasson who has helped me write a work that I hope will be accessible to both the linguist and the New Testament Greek scholar. I am also indebted to Robert Longacre who, as an initial member of my committee, provided helpful insight and needed encouragement during the early stages of this work, to Alicia Massingill for graciously proofing numerous editions of this work in a concise and timely manner, and to other members of the Arlington Baptist College family who have provided assistance and encouragement along the way. Finally, I am grateful to my wife, Diana, whose constant love and understanding have made an otherwise impossible task possible. All errors are of course my own, but there would have been far more without the help of many. -

An Introduction to Dena'ina Grammar

AN INTRODUCTION TO DENA’INA GRAMMAR: THE KENAI (OUTER INLET) DIALECT by Alan Boraas, Ph.D. Professor of Anthropology Kenai Peninsula College Based on reference material by: Peter Kalifornsky James Kari, Ph.D. and Joan Tenenbaum, Ph.D. June 30, 2009 revisions May 22, 2010 Page ii Dedication This grammar guide is dedicated to the 20th century children who had their mouth’s washed out with soap or were beaten in the Kenai Territorial School for speaking Dena’ina. And to Peter Kalifornsky, one of those children, who gave his time, knowledge, and friendship so others might learn. Acknowledgement The information in this introductory grammar is based on the sources cited in the “References” section but particularly on James Kari’s draft of Dena’ina Verb Dictionary and Joan Tenenbaum’s 1978 Morphology and Semantics of the Tanaina Verb. Many of the examples are taken directly from these documents but modified to fit the Kenai or Outer Inlet dialect. All of the stem set and verb theme information is from James Kari’s electronic Dena’ina verb dictionary draft. Students should consult the originals for more in-depth descriptions or to resolve difficult constructions. In addition much of the material in this document was initially developed in various language learning documents developed by me, many in collaboration with Peter Kalifornsky or Donita Peter for classes taught at Kenai Peninsula College or the Kenaitze Indian Tribe between 1988 and 2006, and this document represents a recent installment of a progressively more complete grammar. Anyone interested in Dena’ina language and culture owes a huge debt of gratitude to Dr. -

The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect Version 1.0 July 2007 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: The origin of the pluperfect is the biggest remaining hole in our understanding of the Ancient Greek verbal system. This paper provides a novel unitary account of all four morphological types— alphathematic, athematic, thematic, and the anomalous Homeric form 3sg. ᾔδη (ēídē) ‘knew’—beginning with a “Jasanoff-type” reconstruction in Proto-Indo-European, an “imperfect of the perfect.” © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 The following paper has had a long history (see the first footnote). This version, which was composed as such in the first half of 2006, will be appearing in more or less the present form in volume 46 of the Viennese journal Die Sprache. It is dedicated with affection and respect to the great Indo-Europeanist Jay Jasanoff, who turned 65 in June 2007. *** for Jay Jasanoff on his 65th birthday The Oxford English Dictionary defines the rather sad word has-been as “One that has been but is no longer: a person or thing whose career or efficiency belongs to the past, or whose best days are over.” In view of my subject, I may perhaps be allowed to speculate on the meaning of the putative noun *had-been (as in, He’s not just a has-been; he’s a had-been!), surely an even sadder concept, did it but exist. When I first became interested in the Indo- European verb, thanks to Jay Jasanoff’s brilliant teaching, mentoring, and scholarship, the study of pluperfects was not only not a “had-been,” it was almost a blank slate.