“Superstitious” Beliefs Ruth A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paranormal, Superstitious, Magical, and Religious Beliefs

Paranormal, superstitious, magical, and religious beliefs Kia Aarnio Department of Psychology University of Helsinki, Finland Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Behavioural Sciences at the University of Helsinki in Auditorium XII, Fabianinkatu 33, on the 19th of October, 2007, at 12 o’clock UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Department of Psychology Studies 44: 2007 2 Supervisor Marjaana Lindeman, PhD Department of Psychology University of Helsinki Finland Reviewers Professor Stuart Vyse Department of Psychology Connecticut College USA Timo Kaitaro, PhD Department of Law University of Joensuu Finland Opponent Professor Pekka Niemi Department of Psychology University of Turku Finland ISSN 0781-8254 ISBN 978-952-10-4201-0 (pbk.) ISBN 978-952-10-4202-7 (PDF) http://www.ethesis.helsinki.fi Helsinki University Printing House Helsinki 2007 3 CONTENTS ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................... 6 TIIVISTELMÄ ....................................................................................................................... 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................... 8 LIST OF ORIGINAL PUBLICATIONS ................................................................................ 10 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 11 1.1. Defining paranormal beliefs 12 1.1.1. -

Course Syllabus Or Schedule Will Be Announced Through Elearning

Capstone in London CAP 3130: Science and Pseudoscience: Critiquing the World around You Summer 2022 Instructor: Carolyn Hildebrandt, Ph.D. Contact Information: 1077 Bartlett Hall, 273-7179, [email protected] Pre-Departure Meetings: We will have six meetings on Fridays from 4:00-5:50 p.m. in Bartlett 34. Dates: Feb. 4, Feb. 18, March 4, March 25, April 8, and April 22 Study Abroad in England: May 26 – June 9 Course description: Daily, we are bombarded with interesting and novel breakthroughs involving claims that may or may not be true. In this age of alternative facts and evidence-free assertions, critical thinking is of paramount importance. In this course, students will integrate their knowledge and apply critical thinking and scientific analysis to controversial topics from a broad variety of disciplines. Our home base will be London, where we will visit research institutes, museums, and historic sites. We will also take day trips to Cambridge, Bath, Stonehenge, and Downe. The focus of the class will be multicultural and interdisciplinary. Students from all majors and minors are welcome! Prerequisites: junior standing, 2.5 gpa, acceptance by the UNI Study Abroad Center. Learning Objectives: The purpose of the course is to explore science and pseudoscience from an interdisciplinary, multicultural perspective. Cross-cultural goals include interacting with faculty and students at London University, comparing the study of science and pseudoscience in England and the U.S., and learning about current social and cultural issues -

Behavioral Variability and Rule Generation: General Restricted, and Superstitious Contingency Statements Stuart Vyse Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Psychology Faculty Publications Psychology Department Fall 1991 Behavioral variability and rule generation: general restricted, and superstitious contingency statements Stuart Vyse Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons Recommended Citation Vyse, S. A. (1991). Behavioral variability and rule generation: General, restricted, and superstitious contingency. Psychological Record, 41(4), 487. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Behavioral variability and rule generation: general restricted, and superstitious contingency statements Keywords body language, self culture, reinforcement, performance, stereotypy, problem solving, human behavior Comments Initially published in Psychological Record, Fall 91, p487-506. © 1991 by Southern Illinois University Reprinted with permission: http://thepsychologicalrecord.siu.edu/ This article is available at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychfacpub/6 The Psychological Record, 1991, 41, 487-506 BEHAVIORAL VARIABILITY AND RULE -

REET HIIEMÄE Folkloor Kui Mentaalse Enesekaitse Vahend: Usundilise Pärimuse Pragmaatikast

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library REET HIIEMÄE DISSERTATIONES FOLKLORISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 25 Folkloor kui mentaalseFolkloor enesekaitse usundilise vahend: pärimuse pragmaatikast REET HIIEMÄE Folkloor kui mentaalse enesekaitse vahend: usundilise pärimuse pragmaatikast Tartu 2016 1 ISSN 1406-7366 ISBN 978-9949-77-307-7 DISSERTATIONES FOLKLORISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 25 DISSERTATIONES FOLKLORISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 25 REET HIIEMÄE Folkloor kui mentaalse enesekaitse vahend: usundilise pärimuse pragmaatikast Tartu Ülikooli kultuuriteaduste ja kunstide instituut, eesti ja võrdleva rahvaluule osakond Väitekiri on lubatud kaitsmisele filosoofiadoktori kraadi taotlemiseks (folkloristikas) Tartu Ülikooli kultuuriteaduste ja kunstide instituudi nõukogu otsusega 9. novembril 2016. aastal. Juhendaja: Ülo Valk Oponendid: Merili Metsvahi (Tartu Ülikool) Piret Paal (Klinikum der Universität München, Professur für Spiritual Care) Väitekirja kaitsmine toimub 4. jaanuaril 2017. aastal kell 12.15 Tartu Ülikooli senatisaalis (Ülikooli 18–204). Töö valmimist toetasid Eesti Teadusagentuur (projektid IUT22-5 ja IUT2-43) ning Euroopa Liit Euroopa Regionaalarengu Fondi kaudu (Kultuuriteooria tipp- keskus ja Eesti-uuringute tippkeskus), samuti kõrghariduse rahvusvahelisustu- mise ja mobiilsuse programmid DoRa ja Kristjan Jaak (sihtasutuse Archimedes kaudu). ISSN 1406-7366 ISBN 978-9949-77-307-7 (trükis) ISBN 978-9949-77-308-4 (pdf) Autoriõigus: -

Observf4:R Published by the American Psychological Society Vol

OBSERVf4:R Published by the American Psychological Society Vol. 8, No. I January 1995 • BISTART grants New NIMH grant program is Human Capital Initiative beginning to thin the "graying" ranks ofpsychological Becoming Federal Priority research PIs ........................ 3 High-level federal science policy forum incorporates APS-initiated research plan • A science base for NIDA WASHINGTON, DC, NOVEMBER 21 - The Human Capital Initiative (HCI), which began as a Research organizations help national behavioral science agenda (faithful DbselVer readers will remember), was one formulate NIDA policy ........ 5 of a selected number of priorities under consideration at a recent high-level federal science policy forum here. This is yet another milestone in the HCI's increasingly widespread acceptance by Congress and federal science agencies since being developed • MR and drug treatment under the auspices of APS three years ago. Consensus meeting to be held There are signs that the HCI will advance further, possibly to become one of the in June on mental retardation "cross-cutting" research initiatives that are supported by several agencies. The HCI also and psychopharmacology ... 7 is being expanded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to become a Foundation wide priority. • PHS Commissioned Corps Cross Cutting and Budgeting Cutting Consider a career in the Close to 500 science leaders from academia, government and industry- including a uniformed health/research corps number of psychologists-took part in the event. Speakers included Vice President Al of the Public Health Service .... 9 Gore, National Institutes of Health Director Harold Varmus, Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders, Council of Economic Advisers Chair Laura Tyson, and several other senior Clinton Administration officials. -

Stability Over Time: Is Behavior Analysis a Trait Psychology? Stuart Vyse Connecticut College

The Behavior Analyst 2004, 27, 43-53 No. 1 (Spring) Stability Over Time: Is Behavior Analysis a Trait Psychology? Stuart Vyse Connecticut College Historically, behavior analysis and trait psychology have had little in common; however, recent developments in behavior analysis bring it closer to one of the core assumptions of the trait ap- proach: the stability of behavior over time and, to a lesser extent, environments. The introduction of the concept of behavioral momentum and, in particular, the development of molar theories have produced some common features and concerns. Behavior-analytic theories of stability provide im- proved explanations of many everyday phenomena and make possible the expansion of behavior analysis into areas that have been inadequately addressed. Key words: traits, dispositions, behavioral momentum, molar theory, teleological behaviorism, moral attribution, behavioral stability On the surface, the subtitle of this cial and cultural implications than paper poses a silly question. It is hard those that follow from traditional trait to think of two theoretical viewpoints approaches. more widely separated than behavior analysis and trait psychology (Skinner, Trait Theory 1953). Yet on close examination, con- temporary behavior analysis has in- In their various forms, dispositional creasingly focused on the stability of theories have the longest history and behavior across time and environ- remain among the most popular of all ments, a central concern of trait theo- explanations of human behavior (Carv- ries. In this paper, I argue that, despite er & Scheier, 2004). Dispositional the- their many differences, it is entirely ap- ories hold the common view that peo- propriate for behavior analysts to share ple exhibit relatively stable character- an interest in stable forms of behavior istics across environments and time with trait theorists. -

Consumer Choice and Happiness: a Comparison of the United States and Spain Amani Zaveri Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Psychology Honors Papers Psychology Department 2012 Consumer Choice and Happiness: A Comparison of the United States and Spain Amani Zaveri Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychhp Recommended Citation Zaveri, Amani, "Consumer Choice and Happiness: A Comparison of the United States and Spain" (2012). Psychology Honors Papers. 27. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychhp/27 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Running head: CHOICE AND HAPPINESS 1 Consumer Choice and Happiness: A Comparison of the United States and Spain A thesis presented by Amani Zaveri to the Department of Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May, 2012 CHOICE AND HAPPINESS 2 Abstract The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between decision-making styles and well-being in two different cultures, the United States and Spain. Surveys were administered to 55 participants in Spain and 97 participants in the United States. Participants completed survey measures that assessed maximizing tendencies, the tendency to experience regret, subjective happiness, positive and negative affect, and decision-making tendencies (pre-purchase product comparison, post-purchase product comparison, pre-purchase social comparison, post-purchase social comparison, consumer regret and counterfactual thinking). -

Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel Stuart Vyse Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Psychology Faculty Publications Psychology Department Fall 2001 (Review) World History for Behavior Analysts: Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel Stuart Vyse Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Place and Environment Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Vyse, S. A. (2001). World History for Behavior Analysts: Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel. Behavior & Social Issues, 11(1), 80-87. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. (Review) World History for Behavior Analysts: Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel Keywords Environmentalism, culture, behavior analysts Comments Behavior & Social Issues, Fall 2001, p80-87. © 2001 by the University of Illinois at Chicago Library Article available through http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/bsi This book review is available at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychfacpub/8 Behavior and Social Issues, 11, 80-87 (2001). © Behaviorists for Social Responsibility WORLD HISTORY FOR BEHAVIOR ANALYSTS: JARED DIAMOND’S GUNS, GERMS, AND STEEL Stuart A. Vyse1 Connecticut College Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, contains two important messages for behavior analysts, one a statement of theoretical (and perhaps social-political) kinship and the other a suggestion about scientific methodology and subject matter. -

Elementary School Teachers' Attitudes Toward Classroom Accommodations: the Effects of Disability and School Type

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Psychology Honors Papers Psychology Department 2011 Elementary School Teachers’ Attitudes toward Classroom Accommodations: The ffecE ts of Disability and School Type Sarah Holland Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychhp Part of the Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Sarah, "Elementary School Teachers’ Attitudes toward Classroom Accommodations: The Effects of Disability and School Type" (2011). Psychology Honors Papers. 11. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychhp/11 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Running head: ATTITUDES TOWARD ACCOMMODATIONS Elementary School Teachers’ Attitudes toward Classroom Accommodations: The Effects of Disability and School Type A thesis presented by Sarah Holland to the Department of Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 2011 ATTITUDES TOWARD ACCOMMODATIONS Acknowledgments The challenge of writing a thesis was a daunting one to say the least. Here I am, a year and a half later, with a finished product, and I feel like someone should pinch me to make sure this is not a dream. The number of wonderful people that have helped me along the way serves as a constant reminder of how important it is to surround yourself with good friends, influential advisors, and a supportive family. -

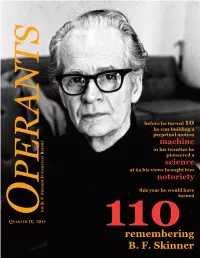

Operants Q4 2014

S T N A before he turned 10 he was building a R perpetual motion T R O machine P E in his twenties he R N pioneered a O E I T A D science N U at 65 his views brought him O F R P E notoriety N N I K this year he would have S . F turned . B E H T O Quarter IV, 2014 1r1eme0 mbering B. F. Skinner from the president In Search for the Perfect Gift his special issue commemorates the 110th anniversary of Skinner’s birth. Since we are Tin the holiday season, I thought I’d write about the difficulties of finding presents for my fa - ther. My husband Ernie and I struggled every year to think of something my father would like. Books or audio recordings should have been easy– but not when my father instantly sent off for any book or recording he wanted. Clothing was out. He had enough pajamas and shirts. And many holidays he received a new silk tie from my mother, purchased at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston where she volunteered. My father appreciated good tools, but he already had a complete set. One holiday, I noticed how beat-up his hammer was, and Ernie and I bought him a new one. He added it to his collection without, we noticed, giving away the old one. I remember, however, two presents that he really valued. The first was a piece of music that I wrote for an assignment in my undergraduate composition class. -

Research Methods Psychology

Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the New England Psychological Association October 12-13, 2012 Worcester Polytechnic Institute Worcester, Massachusetts www.NEPsychological.org Time Campusus Center, Thirdird Floor Salisbalisbury Laboratoratories Period Odeum Odeum Odeum Room Room Room A B C 104 105 115 7:00 AM Regisgistration will openop at 7:00 A.M.M., Campus CeCenter, Third FFloor. to Continentaltal breakfast avaiavailable at 7:3030 AAM in the 9:00 AM Class of 1941948 Cafe, Camppus Center, Sececond Floor. 9:00 AM Poster Session Paper Session Paper Session Howard Psi Chi Symposium I I II Rachlin to (4) (5) 10:00 AM (6-41) (42-45) (46-49) (50) 10:10 AM Poster Session Paper Session Paper Session Ethel Psi Chi Symposium II III IV Tobach to (51) (52) 11:10 AM (53-87) (88-91) (92-95) (96) TThe NEPA Geneneral Meeting (99)9) 11:20 AM Honorary and thee NNEPA Presidentntial Address (100) wwill be Psi Chi Undergraduate heldld iin Salisbury Lababoratories Roomoom 115115. to (98) 12:20 AM Scholar Pre-orderedred lulunches will bee aavailable by 11:000 AAM in the Awards Forkey DinDining Commons,, CCampus Center, FirFirst Floor. & 12:30 PM Fellows +40 Poster Session Paper Session Sharon to 11:20 to 1:00 Symposium III V Symposium Gayle (97) (101) (102-133) (134-137) (138) Horne 1:30 PM (139) 1:40 PM Poster Session Paper Session Science in to Symposium Symposium IV VI Psi Chi Society (140) (141) (142-176) (177-180) (181) Symposium 2:40 PM (182) & 2:50 PM Poster Session Paper Session Alice Symposium V VIII Psi Chi to (189) (253) Locicero 3:50 PM Paper Session (190-248) (249-252) (183) VII (184-188) 4:00 PM ThThe New Englandd PPsychological Assossociation and Psii CChi 2:50 - 4:15 welcome youyour attendance att ththe awards and end-nd-of-meeting recepception (254), to Campusus CCenter, First Flooloor Lobby 5:00 PM 4:4:00 PM - 5:00 PMM Abstracts in this book are numbered sequentially and abstract numbers should be used to locate presentations of interest. -

Guns: Feeling Safe ≠ Being Safe

[ BEHAVIOR & BELIEF STUART VYSE Stuart Vyse is a psychologist and author of Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition, which won the William James Book Award of the American Psychological Association. He is a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Guns: Feeling Safe ≠ Being Safe n the days after the mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, in Ilate 2015, a dear friend who is a single mother made an impassioned plea on her Facebook page. After see- ing many calls for increased gun con- trol, she explained that she had been a victim of assault in the past and would not be giving up her handgun anytime soon. She said maintaining her per- mit was difficult to do—“as it should be”—but she was clearly upset about the many calls for additional controls. While I sympathize with my friend’s desire for security, she has fallen for one of the most common and most dangerous misconceptions Americans hold. According to a 2013 Gallup poll (Swift 2013), the top rea- son U.S. gun owners keep a firearm is for “personal safety/protection.” Fully 60 percent of gun owners gave this The Campaign against Gun pendently associated with an increase reason; the next most common reason Violence Research was “hunting” at 36 percent. in the risk of homicide in the home.” Sadly, buying a gun does not make In 1993, Arthur Kellermann and Indeed, controlling for other factors, you safer. To the contrary, the evi- colleagues published a landmark households where a gun was present dence suggests that bringing a gun study in the New England Journal were 2.7 times more likely to expe- into your home increases the chances of Medicine titled “Gun Ownership rience a homicide and 77 percent of you will be killed.