Rule of Law Symposium 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCL (Singapore) Annual Construction Law Conference 2021 HOPE and FEARS - the Built Environment in the Next Decade Thursday, 23 September 2021 • 9.00 A.M

SCL (Singapore) Annual Construction Law Conference 2021 HOPE AND FEARS - the Built Environment in the Next Decade Thursday, 23 September 2021 • 9.00 a.m. to 5.30 p.m. Hybrid Conference Option of Attending In-Person (Limited Places & Subject to Government Approvals) or Via Zoom Webinar GUEST OF HONOUR & REGISTER HERE KEYNOTE SPEAKER OR SCAN QR CODE Ms Indranee THURAI RAJAH Minister, the Prime Minister’s Office; ABOUT THIS CONFERENCE Second Minister for Finance and National Development; Member of Parliament for Tanjong Hopes and fears – the built environment in the next decade Pagar GRC Business sectors including the built environment have had to and will continue to remould themselves in the shifting sands of the COVID-19 pandemic – there is no certainty that the old normal will ever return. Ms Indranee Rajah is the Minister in the Prime Minister’s This year’s SCL (Singapore) Annual Conference kicks off with Office. She is also Second Minister for Finance, and Second a discussion on transformative technologies and sustainable Minister for National Development. Ms Rajah has been the solutions during project execution before what is hopefully Member of Parliament for the Tanjong Pagar Group an invigorating yet light-hearted debate takes place on Representation Constituency (GRC) since 2001. She was in whether the next decade will bring forth a more collaborative practice as a lawyer and Senior Counsel before joining the working style in the built environment or will a culture of Government. Under her law portfolio from 2012 - 2018, she blame be the prevailing approach. After lunch, various co-chaired the Committees on Family Justice, the formation stakeholders provide their intriguing insights into what could of the Singapore International Commercial Court as well as perhaps be seen as a generational change in the conduct of the Committee to Strengthen Singapore as an International virtual dispute resolution hearings in a post-COVID-19 world. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

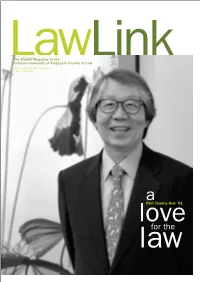

Lawlink Vol.03 Issue 02 Jul - Dec 2004 ISSN: 0219-6441

The Alumni Magazine of the LawNational University of Singapore Faculty of LawLink vol.03 issue 02 jul - dec 2004 ISSN: 0219-6441 a loveProf Tommy Koh ’61 lawfor the contents from the editor DEAN’S MESSAGE03 This year marks the 45th anniversary of the LAW SCHOOL HIGHLIGHTS Law School – how time flies, and how much INAUGURAL ASLI CONFERENCE: EXPLORING LEGAL ISSUES IN AN EMERGING ASIA06 we have grown! COLLEGIATE DINNER08 To commemorate this occasion, we were INTERNATIONAL MOOTING COMPETITIONS 10 privileged to speak to one of our most TEACHING TEACHERS 12 prominent alumni, Professor Tommy Koh MASTERS OF LAW IN INTERNATIONAL ’61. In accepting the NUS 2004 Outstanding BUSINESS LAW IN SHANGHAI 13 Service Award, Prof Koh said that he aspired WHAT’S NEW AT THE CJ KOH LAW LIBRARY 26 “to contribute to NUS Faculty of Law becoming aLAWmnus FEATURE the best in Asia and among the 10 best in TOMMY KOH ’61 the world”. Having seen the Law School from A LOVE FOR THE LAW 17 its inception as a matriculating student in FUTURE ALUMNI 1957, to joining as a member of the teaching EXPANDING THE BOUNDARIES OF KNOWLEDGE staff, then becoming Dean, and now serving SUN HAO CHEN LLM ’05 24 as Chairman of the Law Faculty’s Steering 17TH SINGAPORE LAW REVIEW LECTURE Committee, he has a unique perspective on JEREMY LEONG ’05 25 the development of the Law School. Read LETTER FROM ABROAD what he has to say about Law School (from VIEW FROM THE HILLTOP all angles) on pages 17-19 of this issue. -

ENHANCING “ACCESS to JUSTICE” a Very Good Morning Prof Simon

KEYNOTE ADDRESS OF THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL AT THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE CONFERENCE 2013 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE (17 MAY 2013) ENHANCING “ACCESS TO JUSTICE” A very good morning Prof Simon Chesterman, Dean, NUS Faculty of Law Students, Friends, Ladies & Gentlemen Introduction 1. I am delighted to be here this morning to deliver the keynote address for the second Criminal Justice Conference. A Conference such as this is of particular significance as it serves as a vital platform to discuss some of the more pressing issues pertaining to the criminal justice process and the values that underpin it. Such discussions are both essential and important because, in many ways, the principles and ideals that underpin our criminal justice system also form the foundational ethical building blocks of our society. I accept the reality that each of our individual points of view are informed by our respective perspectives and experiences, and much like any debate informed by a multitude of equally well-reasoned and legitimate views, there is unlikely to be unanimity on the direction the law should be headed, or whether the ideas propounded by the various speakers in this Conference ought to inform the shape of the criminal justice system in the years to come. 2. Be that as it may, I am positive that most would agree with the basic proposition that we must all aim to further the goal of providing “access to justice”. Indeed, the intuitively unobjectionable nature of the proposition is not lost on the Conference organizers this year, who have dedicated the entire first day’s proceedings to this very topic. -

Fulbright Association, Singapore

BBEYOND BARRIERS My Fulbright Experience “The preservation of our free society in the years and decades to come will depend ultimately on whether we succeed or fail in directing the enormous power of human knowledge to the enrichment of our own lives and the shaping of a rational and civilized world order... It is the task of education, more than any other instrument of foreign policy to help close the dangerous gap between the economic and technological interdependence of the people of the world and their psychological, political and spiritual alienation.” [From Prospects for the West, Senator J. William Fulbright] Courtesy of Fulbright Association (U.S.) My Fulbright Experience © 2007 Fulbright Association (Singapore) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording or by information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Fulbright Association (Singapore). Reflections on “My Fulbright Experience” are made in a personal capacity. Permission to reproduce a contribution must also be obtained from the relevant Fulbrighter. Editors Anne Pakir and Jeremy Lim Coordinator Chan Wei Ling Designer Yeoh Kok Cheow Advisor Ang Peng Hwa Resource Panel Rosemary Khoo and Vincent Ooi ISBN 978-981-05-7996-8 Fulbright Association (Singapore) www.fulbright.org.sg CONTENTS DEDICATION 1 Hadijah Bte Rahmat 46 Ho Chee Lick 48 PREFACE 4 Tony T. N. Hung 50 Hussin Mutalib 52 FOREWORD Philip Jeyaretnam 54 Ang Peng Hwa 6 Robert K. Kamei 56 Rosemary Khoo 58 MESSAGES Annie Koh 60 Chan Heng Chee 8 Koh Tai Ann 63 Patricia L. -

Chan Sek Keong the Accidental Lawyer

December 2012 ISSN: 0219-6441 Chan Sek Keong The Accidental Lawyer Against All Odds Interview with Nicholas Aw Be The Change Sustainable Development from Scraps THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE FACULTY OF LAW Contents DEAN’S MESSAGE A law school, more so than most professional schools at a university, is people. We have no laboratories; our research does not depend on expensive equipment. In our classes we use our share of information technology, but the primary means of instruction is the interaction between individuals. This includes teacher and student interaction, of course, but as we expand our project- based and clinical education programmes, it also includes student-student and student-client interactions. 03 Message From The Dean MESSAGE FROM The reputation of a law school depends, almost entirely, on the reputation of its people — its faculty LAW SCHOOL HIGHLIGHTS THE DEAN and staff, its students, and its alumni — and their 05 Benefactors impact on the world. 06 Class Action As a result of the efforts of all these people, NUS 07 NUS Law in the World’s Top Ten Schools Law has risen through the ranks of our peer law 08 NUS Law Establishes Centre for Asian Legal Studies schools to consolidate our reputation as Asia’s leading law school, ranked by London’s QS Rankings as the 10 th p12 09 Asian Law Institute Conference 10 NUS Law Alumni Mentor Programme best in the world. 11 Scholarships in Honour of Singapore’s First CJ Let me share with you just a few examples of some of the achievements this year by our faculty, our a LAWMNUS FEATURES students, and our alumni. -

Brochure 2016 with the Support Of

The IBA-VIAC Mediation and Negotiation Competition 2016 Organized with the support of ELSA Austria Brochure 2016 with the support of Headline Sponsors: 1 Table of Contents I A Word of Welcome from the Organizing Team 3 II. A Word of Welcome from the International Bar Association (IBA) 4 III. A word of Welcome from the Vienna International Arbitral Centre (VIAC) 5 IV. The Organizers 6 V. International Advisory Board 14 VI. Scoring and Feedback Working Group 17 VII. Case Working Group 19 VIII. Competition Schedule Overview and Details 22 IX. Sponsors and Supporters 26 X. Workshops on 28 June 31 XI. Expert Assessors 37 XII. Mediator Teams 57 XIII. Negotiator Teams 67 XIV. Useful Information (venues, maps, numbers, lunch options & more) 91 2 Words of Welcome I. A Word of Welcome from the Organizing Team On behalf of the Organizing Team of CDRC Vienna 2016 we are very proud to welcome you to the second IBA-VIAC Consensual Dispute Resolution Competition - CDRC Vienna. Following our successful premier in 2015, Vienna has the honor to welcome, for the second time, participants from over 40 countries that will be part of shaping the future of Consensual Dispute Resolution. Only one year ago, CDRC Vienna put into practice for the first time it's vision for a new generation of dispute resolution. A vision to foster the use of mediation and negotiation to become the future way to resolve and prevent disputes on a national and international level. 16 student teams were selected from almost 40 applications and 30 professionals honored the event with their experience and expertise. -

Engaging New Media: Challenging Old Assumptions, Is Our First

// ENGAGING NEW MEDIA / / CHALLENGING OLD ASSUMPTIONS A report by the Advisory Council on the Impact of New Media on Society (AIMS) December 2008 // ENGAGING NEW MEDIA / / CHALLENGING OLD ASSUMPTIONS A report by the Advisory Council on the Impact of New Media on Society Singapore December 2008 Published December 2008 ISSN 1793-8961 © Advisory Council on the Impact of New Media on Society All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanised, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. TABLE OF CONTENTS p 2—3 // Foreword / p 5—9 // Introduction / p 11—25 // Executive Summary / p 27—49 Chapter 1 // E-Engagement / / Trends in New Media / Why Engage Online? / Embarking on E-Engagement / E-Participation / Barriers to E-Engagement / Reasons for E-Engagement / Risk Assessment / Public Feedback / Recommendations Following Public Feedback / Conclusion p 51—78 Chapter 2 // Online Political Content / / Background / Review of Light-touch Policy / Online Election Advertising in Other Countries / Proposed Recommendations in the Consultation Paper / Public Feedback / Recommendations Following Public Feedback / Conclusion p 80—107 Chapter 3 // Protection of Minors / / Risks to Minors / How are these Risks Managed? / The Key Lies in Education / What is Being Done in Singapore / Proposed Recommendations in the Consultation Paper / Public Feedback / AIMS' Views / Recommendations Following Public Feedback -

Small Law Firms 92 Social and Welfare 94 Solicitors’ Accounts Rules 97 Sports 98 Young Lawyers 102 ENHANCING PROFESSIONAL 03 STANDARDS 04 SERVING the COMMUNITY

OUR MISSION To serve our members and the community by sustaining a competent and independent Bar which upholds the rule of law and ensures access to justice. 01 OUR PEOPLE 02 GROWING OUR PRACTICE The Council 3 Advocacy 51 The Executive Committee 4 Alternative Dispute Resolution 53 Council Report 5 Civil Practice 56 The Secretariat 7 Continuing Professional Development 59 President’s Message 8 Conveyancing Practice 61 CEO’s Report 15 Corporate Practice 63 Treasurer’s Report 27 Criminal Practice 65 Audit Committee Report 31 Cybersecurity and Data Protection 68 Year in Review 32 Family Law Practice 70 Statistics 48 Information Technology 73 Insolvency Practice 74 Intellectual Property Practice 76 International Relations 78 Muslim Law Practice 81 Personal Injury and Property Damage 83 Probate Practice and Succession Planning 85 Publications 87 Public and International Law 90 Small Law Firms 92 Social and Welfare 94 Solicitors’ Accounts Rules 97 Sports 98 Young Lawyers 102 ENHANCING PROFESSIONAL 03 STANDARDS 04 SERVING THE COMMUNITY Admissions 107 Compensation Fund 123 Anti-Money Laundering 109 Professional Indemnity 125 Inquiries into Inadequate Professional Services 111 Report of the Inquiry Panel 113 05 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 06 PRO BONO SERVICES 128 132 07 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 227 This page is intentionally left blank. OUR PEOPLE The council (Seated L to R): Lim Seng Siew, M Rajaram (Vice-President), Gregory Vijayendran (President), Tito Shane Isaac, Adrian Chan Pengee (Standing L to R): Sui Yi Siong (Xu Yixiong), Ng Huan Yong, Simran Kaur Toor, -

Report of the Committee to Develop the Singapore Legal Sector

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE TO DEVELOP THE SINGAPORE LEGAL SECTOR _________________________________________ FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 2007 Report of the Committee to Develop the Singapore Legal Sector Table of Contents 1 BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 1 2 LEGAL EDUCATION ............................................................................................. 2 (A) Legal Academia............................................................................................ 3 (I) Changing Legal Education Landscape......................................... 3 (II) Synergy between Academia and Industry .................................. 5 (III) Recommendations........................................................................... 5 (B) ‘A’ Level Law................................................................................................ 7 (I) Potential Benefits of Introducing ‘A’ Level Law......................... 8 (II) Costs of Implementing ‘A’ Level Law.......................................... 8 (III) Recommendation............................................................................. 9 (C) Restructuring the Present Legal Education System.............................. 9 (I) Admission Criteria for Law Schools............................................. 9 (II) Structure of the LLB Course..........................................................10 (III) Review of Content..........................................................................12 -

Brought to You by the FOCC Marketing Committee 18/19 Freshmen Handbook 2 0 1 9 Message from the Marketing Committee

Brought to you by the FOCC to Brought 18/19 Committee Marketing Freshmen Handbook 2 0 1 9 Message from the Marketing Committee Hi Freshies! When we first started planning this Orientation, we wanted to create an unforgettable Orientation experience filled with laughter, cheer and banter. More importantly, we wanted to give you a taste of the great four years that you will have in NUS Law. The next few years in law school will definitely be tough. It will not be an easy stroll through Botanic Gardens, or a simple dip in the pool at CCAB. However, it will also be an extremely rewarding and fulfilling experience. No matter how tough times get, remember to always be here for each other and support each other. Always remember to take a break and hydrate yourselves. Orientation is just the beginning of all the friends you will make and good times you will have in law school. We hope that you’ve enjoyed Orientation as much as we have. Have the bestest year ahead! With all the love + lawsku muggers + Fu Shan’s Deans Lister Power, Kai Le, Ashley, Fu Shan The Marketing Committee 2018/19 P.S. Join Marketing Committee next year! :DDD 1 Table of Content 03 Getting to know BTC 05 Places to Eat 1 2 Muggers Getting to know BTC 03 Places to Eat 05 Study Areas 07 Useful Links 08 The FOCC 11 Muggers 12 Social Media Feature 13 Copyright and Disclaimer Sponsorship Profiles 14 All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopy, recording or otherwise without prior permission from the committee.