Challenges to Legal Education in a Changing Landscape—A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

SCL (Singapore) Annual Construction Law Conference 2021 HOPE and FEARS - the Built Environment in the Next Decade Thursday, 23 September 2021 • 9.00 A.M

SCL (Singapore) Annual Construction Law Conference 2021 HOPE AND FEARS - the Built Environment in the Next Decade Thursday, 23 September 2021 • 9.00 a.m. to 5.30 p.m. Hybrid Conference Option of Attending In-Person (Limited Places & Subject to Government Approvals) or Via Zoom Webinar GUEST OF HONOUR & REGISTER HERE KEYNOTE SPEAKER OR SCAN QR CODE Ms Indranee THURAI RAJAH Minister, the Prime Minister’s Office; ABOUT THIS CONFERENCE Second Minister for Finance and National Development; Member of Parliament for Tanjong Hopes and fears – the built environment in the next decade Pagar GRC Business sectors including the built environment have had to and will continue to remould themselves in the shifting sands of the COVID-19 pandemic – there is no certainty that the old normal will ever return. Ms Indranee Rajah is the Minister in the Prime Minister’s This year’s SCL (Singapore) Annual Conference kicks off with Office. She is also Second Minister for Finance, and Second a discussion on transformative technologies and sustainable Minister for National Development. Ms Rajah has been the solutions during project execution before what is hopefully Member of Parliament for the Tanjong Pagar Group an invigorating yet light-hearted debate takes place on Representation Constituency (GRC) since 2001. She was in whether the next decade will bring forth a more collaborative practice as a lawyer and Senior Counsel before joining the working style in the built environment or will a culture of Government. Under her law portfolio from 2012 - 2018, she blame be the prevailing approach. After lunch, various co-chaired the Committees on Family Justice, the formation stakeholders provide their intriguing insights into what could of the Singapore International Commercial Court as well as perhaps be seen as a generational change in the conduct of the Committee to Strengthen Singapore as an International virtual dispute resolution hearings in a post-COVID-19 world. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

Compromising on Consideration in Singapore: Gay Choon Ing V Loh Sze Ti Terence Peter Goh Yihan*

Supreme Court of Singapore, 1 Supreme Court Lane, Singapore 178879, t: (65)-6332-1020 _________________________________________________________________________________________________ We are grateful to the authors, editors and publishers for their kind permission granted to post the respective articles on the Singapore Judicial College website. No article posted here may be circulated or reproduced without the prior permission of the author(s), editor(s) and publisher (where applicable). Our Vision: Excellence in judicial education and research. Our Mission: To provide and inspire continuing judicial learning and research to enhance the competency and professionalism of judges. Compromising on consideration in Singapore: Gay Choon Ing v Loh Sze Ti Terence Peter Goh Yihan* Introduction It is not often that a judgment contains a reference to Aris- tal difficulties’.5 The facts that allowed the opportunity to totle’s work or a coda at its conclusion. The recent Singa- re-evaluate consideration reflected the ebb and flow of pore Court of Appeal1 judgment of Gay Choon Ing v Loh friendship, captured by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics Sze Ti Terence Peter2 (delivered by Andrew Phang JA) con- (Book VIII),6 and interestingly cited by the Court in a rare tained both, the latter of which an extensive judicial expo- judicial nod to classical literature.7 The appellant in Gay sition on the difficulties (and tentative solutions) relating to Choon Ing was a close friend of the respondent and was the contractual doctrine of consideration. This re-evalua- employed by the latter’s company in Kenya, ASP, until his tion of consideration at the slightest opportunity is unsur- resignation in 2004. -

Two Contrasting Approaches in the Interpretation of Outdated Statutory Provisions Yihan GOH Singapore Management University, [email protected]

Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School Of Law School of Law 12-2010 Two Contrasting Approaches in the Interpretation of Outdated Statutory Provisions Yihan GOH Singapore Management University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Courts Commons, and the Legislation Commons Citation GOH, Yihan. Two Contrasting Approaches in the Interpretation of Outdated Statutory Provisions. (2010). Singapore Journal of Legal Studies. [2010], 530-545. Research Collection School Of Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/1415 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Law by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2010] 530-545 Published in Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, [2010] pp 530-545. TWO CONTRASTING APPROACHES IN THE INTERPRETATION OF OUTDATED STATUTORY PROVISIONS WX v. WW' AAG v. Estate ofAAH, deceased2 GOH YIHAN* I. INTRODUCTION Some statutes in operation today were passed a long time ago. Inevitably, through the passage of time, social norms at the time of enactment may now be unrecognis- able. The legislative intent at the time of enactment may also seem outdated in more modem times. Judges interpreting specific provisions of these statutes may therefore encounter problems in ensuring a 'just' result in an instant case. -

Constitutional Documents of All Tcountries in Southeast Asia As of December 2007, As Well As the ASEAN Charter (Vol

his three volume publication includes the constitutional documents of all Tcountries in Southeast Asia as of December 2007, as well as the ASEAN Charter (Vol. I), reports on the national constitutions (Vol. II), and a collection of papers on cross-cutting issues (Vol. III) which were mostly presented at a conference at the end of March 2008. This collection of Constitutional documents and analytical papers provides the reader with a comprehensive insight into the development of Constitutionalism in Southeast Asia. Some of the constitutions have until now not been publicly available in an up to date English language version. But apart from this, it is the first printed edition ever with ten Southeast Asian constitutions next to each other which makes comparative studies much easier. The country reports provide readers with up to date overviews on the different constitutional systems. In these reports, a common structure is used to enable comparisons in the analytical part as well. References and recommendations for further reading will facilitate additional research. Some of these reports are the first ever systematic analysis of those respective constitutions, while others draw on substantial literature on those constitutions. The contributions on selected issues highlight specific topics and cross-cutting issues in more depth. Although not all timely issues can be addressed in such publication, they indicate the range of questions facing the emerging constitutionalism within this fascinating region. CONSTITUTIONALISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Volume 2 Reports on National Constitutions (c) Copyright 2008 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Editors Clauspeter Hill Jőrg Menzel Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 Tel: +65 6227 2001 Fax: +65 6227 2007 All rights reserved. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

AY2020-2021 Class Timetable

ACADEMIC YEAR 2020/2021 ‐ SEMESTER 1 Page 1: Semester 1 AY2020‐2021 Timetable (ver 23 July 2020) Version 23 July 2020 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE LC1003 LAW OF CONTRACT LECTURE {Yale 2} CORE LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL 1 {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL BURTON ONG, WAYNE COURTNEY, DORA NEO, KELRY LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL {Yale 2} ELEANOR WONG LOI, TIMOTHY LIAU, ALLEN SNG, BENJAMIN WONG Weekly YEAR LC2004 PRINCIPLES OF PROPERTY LAW CORE LECTURE {Yale 3} LC2008A,D & E COMPANY LAW [SECTIONS A, D & E] LC2008C & F COMPANY LAW [SECT C & F] {Yale 4} 2 TEO KEANG SOOD, CHEN WEITSENG, TARA DAVENPORT, KENNETH KHOO, ERNEST LIM, MICHAEL EWING‐CHOW UMAKANTH VAROTTIL, WALTER WOON Weekly HU YING, DARYL YONG, WILLIAM RICQUIER, ELAINE CHEW YEAR LC3001A EVIDENCE (A) LECTURE {Yale 5} CORE JEFFREY PINSLER, CHIN TET YUNG, HO HOCK LAI, MATTHEW SEET UPPER Weekly YR LC6378 DOCTORAL WORKSHOP LC5337 SINGAPORE COMMON LAW OF CONTRACT DAMIAN CHALMERS CORE [Week 1 ‐ 6] Non‐IBL Group 1 LC5405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (A) Weekly HELENA WHALEN‐BRIDGE GD NG‐LOY WEE LOON LL4177V/LL5177V/LL6177V ENTERTAINMENT LAW: POP ICONOGRAPHY & CELEBRITY LL4405A/LL5405A/LC5405A/LL6405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A LL4033V/LL5033V/LL6033V INTERNATIONAL LEGAL PROCESS DAVID TAN NG‐LOY WEE LOON ELEANOR WONG, CHEN ZHIDA , TIONG TECK WEE LL4029BV/LL5029BV/LL6029BV INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION LL4317V/LL5317V/LL6317V INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION IN -

Competing Narratives and Discourses of the Rule of Law in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2012] 298–330 SHALL THE TWAIN NEVER MEET? COMPETING NARRATIVES AND DISCOURSES OF THE RULE OF LAW IN SINGAPORE Jack Tsen-Ta Lee∗ This article aims to assess the role played by the rule of law in discourse by critics of the Singapore Government’s policies and in the Government’s responses to such criticisms. It argues that in the past the two narratives clashed over conceptions of the rule of law, but there is now evidence of convergence of thinking as regards the need to protect human rights, though not necessarily as to how the balance between rights and other public interests should be struck. The article also examines why the rule of law must be regarded as a constitutional doctrine in Singapore, the legal implications of this fact, and how useful the doctrine is in fostering greater solicitude for human rights. Singapore is lauded for having a legal system that is, on the whole, regarded as one of the best in the world,1 and yet the Government is often vilified for breaching human rights and the rule of law. This is not a paradox—the nation ranks highly in surveys examining the effectiveness of its legal system in the context of economic compet- itiveness, but tends to score less well when it comes to protection of fundamental ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, School of Law, Singapore Management University. I wish to thank Sui Yi Siong for his able research assistance. 1 See e.g., Lydia Lim, “S’pore Submits Human Rights Report to UN” The Straits Times (26 February 2011): On economic, social and cultural rights, the report [by the Government for Singapore’s Universal Periodic Review] lays out Singapore’s approach and achievements, and cites glowing reviews by leading global bodies. -

SGCA 50 Civil Appeal No 185 of 2019 and Summons No 51 of 2020 Between Alphire Group Pte

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2020] SGCA 50 Civil Appeal No 185 of 2019 and Summons No 51 of 2020 Between Alphire Group Pte Ltd … Applicant / Appellant And Law Chau Loon … Respondent In the matter of HC/Originating Summons No 730 of 2019 In the matter of Order 45, Rule 11 of the Rules of Court (Cap 322, Rule 5) Between Law Chau Loon … Applicant And Alphire Group Pte Ltd … Respondent EX TEMPORE JUDGMENT [Agency] — [Implied authority of agent] — [Settlement agreement] [Contract] — [Formation] — [Identifiable agreement that is complete and certain] ii This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Alphire Group Pte Ltd v Law Chau Loon and another matter [2020] SGCA 50 Court of Appeal — Civil Appeal No 185 of 2019 and Summons No 51 of 2020 Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA, Woo Bih Li J and Quentin Loh J 19 May 2020 19 May 2020 Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA (delivering the judgment of the court ex tempore): 1 We first deal with the appellant’s application in Summons No 51 of 2020 (“SUM 51”) to strike out paras 19(a), 19(b), 20 and 21 of the respondent’s case, as well as certain documents exhibited under S/N 2 of the respondent’s supplementary core bundle, which consist of exhibits of the respondent’s affidavit of evidence-in-chief in Suit No 822 of 2015 (“Suit 822”). -

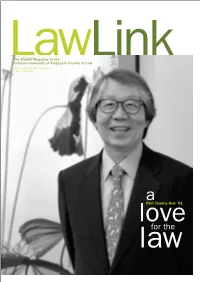

Lawlink Vol.03 Issue 02 Jul - Dec 2004 ISSN: 0219-6441

The Alumni Magazine of the LawNational University of Singapore Faculty of LawLink vol.03 issue 02 jul - dec 2004 ISSN: 0219-6441 a loveProf Tommy Koh ’61 lawfor the contents from the editor DEAN’S MESSAGE03 This year marks the 45th anniversary of the LAW SCHOOL HIGHLIGHTS Law School – how time flies, and how much INAUGURAL ASLI CONFERENCE: EXPLORING LEGAL ISSUES IN AN EMERGING ASIA06 we have grown! COLLEGIATE DINNER08 To commemorate this occasion, we were INTERNATIONAL MOOTING COMPETITIONS 10 privileged to speak to one of our most TEACHING TEACHERS 12 prominent alumni, Professor Tommy Koh MASTERS OF LAW IN INTERNATIONAL ’61. In accepting the NUS 2004 Outstanding BUSINESS LAW IN SHANGHAI 13 Service Award, Prof Koh said that he aspired WHAT’S NEW AT THE CJ KOH LAW LIBRARY 26 “to contribute to NUS Faculty of Law becoming aLAWmnus FEATURE the best in Asia and among the 10 best in TOMMY KOH ’61 the world”. Having seen the Law School from A LOVE FOR THE LAW 17 its inception as a matriculating student in FUTURE ALUMNI 1957, to joining as a member of the teaching EXPANDING THE BOUNDARIES OF KNOWLEDGE staff, then becoming Dean, and now serving SUN HAO CHEN LLM ’05 24 as Chairman of the Law Faculty’s Steering 17TH SINGAPORE LAW REVIEW LECTURE Committee, he has a unique perspective on JEREMY LEONG ’05 25 the development of the Law School. Read LETTER FROM ABROAD what he has to say about Law School (from VIEW FROM THE HILLTOP all angles) on pages 17-19 of this issue. -

ENHANCING “ACCESS to JUSTICE” a Very Good Morning Prof Simon

KEYNOTE ADDRESS OF THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL AT THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE CONFERENCE 2013 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE (17 MAY 2013) ENHANCING “ACCESS TO JUSTICE” A very good morning Prof Simon Chesterman, Dean, NUS Faculty of Law Students, Friends, Ladies & Gentlemen Introduction 1. I am delighted to be here this morning to deliver the keynote address for the second Criminal Justice Conference. A Conference such as this is of particular significance as it serves as a vital platform to discuss some of the more pressing issues pertaining to the criminal justice process and the values that underpin it. Such discussions are both essential and important because, in many ways, the principles and ideals that underpin our criminal justice system also form the foundational ethical building blocks of our society. I accept the reality that each of our individual points of view are informed by our respective perspectives and experiences, and much like any debate informed by a multitude of equally well-reasoned and legitimate views, there is unlikely to be unanimity on the direction the law should be headed, or whether the ideas propounded by the various speakers in this Conference ought to inform the shape of the criminal justice system in the years to come. 2. Be that as it may, I am positive that most would agree with the basic proposition that we must all aim to further the goal of providing “access to justice”. Indeed, the intuitively unobjectionable nature of the proposition is not lost on the Conference organizers this year, who have dedicated the entire first day’s proceedings to this very topic.