A Study of Regional Organization at Banavasi, C. 1 St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the High Court of Karnataka Dharwad Bench

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA DHARWAD BENCH DATED THIS THE 21 ST DAY OF JANUARY, 2019 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE H.P. SANDESH CRIMINAL PETITION NO.100303/2015 BETWEEN : 1. SHANIYAR S/O NAGAPPA NAIK, AGE: 44 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: BIDRAMANE, BASTI-KAIKINI, MURDESHWAR, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTARA KANNADA. 2. MANJAPPA S/O DURGAPPA NAIK, AGE: 33 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: BEERANNANA MANE, TOODALLI, MURDESHWAR, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTAR KANNADA. 3. MADEV S/O NARAYAN NAIK, AGE: 42 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: MOLEYANA MANE, DODDABALSE, MURDESHWAR, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTAR KANNADA. 4. MOHAN S/O SHANIYAR NAIK, AGE: 40 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: KODSOOLMANE, DIVAGIRI, MURDESHWAR, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTAR KANNADA. 2 5. BHASKAR S/O MASTAPPA NAIK, AGE: 42 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: BAILAPPANA MANE, MUTTALLI, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTAR KANNADA. 6. HAMEED SAB S/O BABASAHEB, AGE: 56 YEARS, OCC: BUSINESS, R/O: MEMMADI, TQ: KUNDAPUR, DIST: UDUPI. 7. MANJUNATH S/O NAGAPPA NAIK, AGE: 45 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: KONERUMANE, CHOUTHANI, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTARA KANNADA. 8. HONNAPPA S/O NARAYANA MOGER, AGE: 34 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: MUNDALLI, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTARA KANNADA. 9. TIRUMALA S/O GANAPATI MOGER, AGE: 29 YEARS, OCC: BUSINESS, R/O: BIDRAMANE, MURDESHWAR, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTARA KANNADA. 10. MANJUNATH S/O JATTAPPA NAIK, AGE: 58 YEARS, OCC: BUSINESMAN, R/O: HANUMAN NAGAR, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTARA KANNADA. 3 11. YOGESH S/O NARAYANA DEVADIGA, AGE: 42 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURIST, R/O: MOODABHAKTAL, MUTTALLI, TQ: BHATKAL, DIST: UTTARA KANNADA. …PETITIONERS (BY SRI.GANAPATI M BHAT, ADVOCATE) AND : THE STATE OF KARNATAKA, BY ITS P.S.I., MURDESHWAR POLICE STATION, REPRESENTED BY STATE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR, HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, DHARWAD-580 011. -

Rural Tourism As an Entrepreneurial Opportunity (A Study on Hyderabad Karnataka Region)

Volume : 5 | Issue : 12 | December-2016 ISSN - 2250-1991 | IF : 5.215 | IC Value : 79.96 Original Research Paper Management Rural Tourism as an Entrepreneurial Opportunity (a Study on Hyderabad Karnataka Region) Assistant Professor, Dept of Folk Tourism,Karnataka Folklore Mr. Hanamantaraya University, Gotagodi -581197,Shiggaon TQ Haveri Dist, Karnataka Gouda State, India Assistant Professor, Dept of Folk Tourism,Karnataka Folklore Mr. Venkatesh. R University, Gotagodi -581197,Shiggaon TQ Haveri Dist, Karnataka State, India The Tourism Industry is seen as capable of being an agent of change in the landscape of economic, social and environment of a rural area. Rural Tourism activity has also generated employment and entrepreneurship opportunities to the local community as well as using available resources as tourist attractions. There are numerable sources to lead business in the tourism sector as an entrepreneur; the tourism sector has the potential to be a development of entrepreneurial and small business performance. Which one is undertaking setting up of business by utilizing all kinds sources definitely we can develop the region of that area. This article aims to discuss the extent of entrepreneurial opportunities as the development ABSTRACT of tourism in rural areas. Through active participation among community members, rural entrepreneurship will hopefully move towards prosperity and success of rural tourism entrepreneurship Rural Tourism, Entrepreneurial opportunities of Rural Tourism, and Development of Entrepre- KEYWORDS neurship in Rural area Introduction Objectives of the studies Top tourism destinations, particularly in developing countries, 1. To know the entrepreneurial opportunities in Rural are include national parks, wilderness areas, mountains, lakes, and of HK region cultural sites, most of which are generally rural. -

Hoysala King Ballala Iii (1291-1342 A.D)

FINAL REPORT UGC MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT on LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA III (1291-1342 A.D) Submitted by DR.N.SAVITHRI Associate Professor Department of History Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s Arts and Commerce College, Mysore-24 Submitted to UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION South Western Regional Office P.K.Block, Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560009 2017 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to Express My Gratitude and Indebtedness to University Grants Commission, New Delhi for awarding Minor Research Project in History. My Sincere thanks are due to Sri.Paramashivaiah.S, President of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I am Grateful to Prof.Panchaksharaswamy.K.N, Honorary Secretary of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I owe special thanks to Principal Sri.Dhananjaya.Y.D., Vice Principal Prapulla Chandra Kumar.S., Dr.Saraswathi.N., Sri Purushothama.K, Teaching and Non-Teaching Staff, members of Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s College, Mysore. I also thank K.B.Communications, Mysore has taken a lot of strain in computerszing my project work. I am Thankful to the Authorizes of the libraries in Karnataka for giving me permission to consult the necessary documents and books, pertaining to my project work. I thank all the temple guides and curators of minor Hoysala temples like Belur, Halebidu. Somanathapura, Thalkad, Melkote, Hosaholalu, kikkeri, Govindahalli, Nuggehalli, ext…. Several individuals and institution have helped me during the course of this study by generously sharing documents and other reference materials. I am thankful to all of them. Dr.N.Savithri Place: Date: 2 CERTIFICATE I Dr.N. Savithri Certify that the project entitled “LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA iii (1299-1342 A.D)” sponsored by University Grants Commission New Delhi under Minor Research Project is successfully completed by me. -

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes Posted On April 28, 2020 By Cgpsc.Info Home » CGPSC Notes » History Notes » Gupta Empire and Their Rulers Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – The Gupta period marks the important phase in the history of ancient India. The long and e¸cient rule of the Guptas made a huge impact on the political, social and cultural sphere. Though the Gupta dynasty was not widespread as the Maurya Empire, but it was successful in creating an empire that is signiÛcant in the history of India. The Gupta period is also known as the “classical age” or “golden age” because of progress in literature and culture. After the downfall of Kushans, Guptas emerged and kept North India politically united for more than a century. Early Rulers of Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) :- Srigupta – I (270 – 300 C.E.): He was the Ûrst ruler of Magadha (modern Bihar) who established Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) with Pataliputra as its capital. Ghatotkacha Gupta (300 – 319 C.E): Both were not sovereign, they were subordinates of Kushana Rulers Chandragupta I (319 C.E. to 335 C.E.): Laid the foundation of Gupta rule in India. He assumed the title “Maharajadhiraja”. He issued gold coins for the Ûrst time. One of the important events in his period was his marriage with a Lichchavi (Kshatriyas) Princess. The marriage alliance with Kshatriyas gave social prestige to the Guptas who were Vaishyas. He started the Gupta Era in 319-320C.E. Chandragupta I was able to establish his authority over Magadha, Prayaga,and Saketa. Calendars in India 58 B.C. -

Archaeology of Roman Maritime Commerce in Peninsular India

C hapter V Archaeology Of Roman Maritime Commerce in Peninsular India The impact of Roman maritime commerce on the socio-economic fabric of Early Historic India has been the theme of historical reconstructions from archaeology Perhaps the most forceful projection of this theme was made by (Ghosh 1989:132) who says with regard to the urbanization of peninsular India that the ‘early historical period of south and south-west India seems to have had its own peculiarities. Though, as in neighbouring regions it originated in the midst of megaliths, its driving force arose not so much out of north Indian contacts as trade with the Roman World in the 1 St century B C , particularly resulting in the establishment of seaports and emporia. ’ Mehta (1983:139-148), also argues for Roman trade contact catalysing processes of urbanization in the Gujarat-Maharashtra region Ray (1987: 94-104) in her study of urbanization of the Deccan, points out that ‘ enormous expansion of inland trade networks in the subcontinent, coupled with increased maritime activity between the west coast and the Red Sea ports of the Roman Empire led to the rise of urban centres at vantage points along the trade-routes and in the peripheral. and hitherto unoccupied areas ’ Similarly, Sharma (1987) endeavours to build a case for widespread deurbanization in the subcontinent in the 3rd cenury A D caused, among other factors, by the collapse of Indo-Roman trade In the conclusion to his analysis of urban decay in India, Sharma (1987 180) says ‘ the Kusana and Satavahana urban centres -

Loukota 2019

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Goods that Cannot Be Stolen: Mercantile Faith in Kumāralāta’s Garland of Examples Adorned by Poetic Fancy A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Diego Loukota Sanclemente 2019 © Copyright by Diego Loukota Sanclemente 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Goods that Cannot Be Stolen: Mercantile Faith in Kumāralāta’s Garland of Examples Adorned by Poetic Fancy by Diego Loukota Sanclemente Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Gregory Schopen, Co-chair Professor Stephanie J. Watkins, Co-chair This dissertation examines the affinity between the urban mercantile classes of ancient India and contemporary Buddhist faith through an examination of the narrative collection Kalpanāmaṇḍitikā Dṛṣṭāntapaṅkti (“Garland of Examples,” henceforth Kumāralāta’s Garland) by the 3rd Century CE Gandhāran monk Kumāralāta. The collection features realistic narratives that portray the religious sensibility of those social classes. I contend that as Kumāralāta’s 3rd Century was one of crisis for cities and for trade in the Indian world, his work reflects an urgent statement of the core values of ii Buddhist urban businesspeople. Kumāralāta’s stories emphasize both religious piety and the pursuit of wealth, a concern for social respectability, a strong work ethic, and an emphasis on rational decision-making. These values inform Kumāralāta’s religious vision of poverty and wealth. His vision of religious giving conjugates economic behavior and religious doctrine, and the outcome is a model that confers religious legitimation to the pursuit of wealth but also an economic outlet for religious fervor and a solid financial basis for the monastic establishment, depicted by Kumāralāta in close interdependence with the laity and, most importantly, within the same social class. -

Karnataka and Mysore

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY October 22, 1955 Views on States Reorganisation - / Karnataka and Mysore K N Subrahmanya THE recommendation of the States 4 the South Kanara district except will show vision and broadminded- Reorganisation Commission to Kasaragod taluk; ness in dealing with the Kannada form a Karnataka State bring 5 the Kollegal taluk of the Coim- population of the area in question ing together predominantly Kan batore district of Madras; and will provide for adequate educa nada-speaking areas presently scat 6 Coorg. tional facilities for them and also tered over five States has been ensure that they are not discriminat generally welcomed by a large sec The State thus formed will have ed against in the matter of recruit tion of Kannadigas who had a a population of 19 million and an ment to services." How far this genuine, long-standing complaint area of 72,730 square miles. paternal advice will be heeded re that their economic and cultural pro Criticism of the recommendations of mains to be seen. In this connection, gress was hampered owing to their the Commission, so far as it relates one fails to appreciate the attempt of numerical inferiority in the States to Karnataka State, falls into two the Commission to link up the Kolar dominated by other linguistic groups. categories. Firstly, there are those question with that of Bellary. In There is a feeling of satisfaction who welcome the suggestion to form treating Kolar as a bargaining coun among the Kannadigas over the a Karnataka State but complain that ter, the Commission has thrown to Commission's approach to the ques the Commission has excluded certain winds the principles that they had tion of the formation of a Karoatal.a areas, which on a purely linguistic set before them. -

A Study of Buddhist Sites in Karnataka

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicjournal.in Volume 3; Issue 6; November 2018; Page No. 215-218 A study of Buddhist sites in Karnataka Dr. B Suresha Associate Professor, Department of History, Govt. Arts College (Autonomous), Chitradurga, Karnataka, India Abstract Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha wandered the country side teaching what he had learned. He organized a community of monks known as the ‘Sangha’ to continue his teachings ofter his death. They preached the world, known as the Dharma. Keywords: Buddhism, meditation, Aihole, Badami, Banavasi, Brahmagiri, Chandravalli, dermal, Haigunda, Hampi, kanaginahally, Rajaghatta, Sannati, Karnataka Introduction of Ashoka, mauryanemperor (273 to 232 B.C.) it gained royal Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the support and began to spread more widely reaching Karnataka history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was and most of the Indian subcontinent also. Ashokan edicts founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of which are discovered in Karnataka delineating the basic tents Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got of Buddhism constitute the first written evidence about the enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha presence of the Buddhism in Karnataka. -

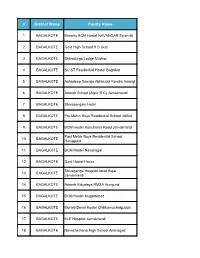

District Name Facilty Name

# District Name Facilty Name 1 BAGALKOTE Minority BCM Hostel NAVANGAR Sctor-46 2 BAGALKOTE Govt High School H S Gutti 3 BAGALKOTE Shivadurga Lodge Mudhol 4 BAGALKOTE SC ST Residential Hostel Bagalkot 5 BAGALKOTE Ashadeep Samaja Abhiruddi Kendra Asangi 6 BAGALKOTE Adarsh School (Algur R C) Jamakhandi 7 BAGALKOTE Shivasangam Hotel 8 BAGALKOTE Pre Metric Boys Residential School Jalihal 9 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Kunchanur Road Jamakhandi Post Metric Boys Residential School 10 BAGALKOTE Hunagund 11 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Navanagar 12 BAGALKOTE Govt Hostel Hosur Shivaganga Hospital Jolad Bajar 13 BAGALKOTE Jamakhandi 14 BAGALKOTE Adarsh Vidyalaya RMSA Hungund 15 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Mugalakhod 16 BAGALKOTE Morarji Desai Hostel Chikkamuchalgudda 17 BAGALKOTE KLE Hospital Jamakhandi 18 BAGALKOTE Navachethana High School Aminagad 19 BAGALKOTE Omkar Lodge Mudhol 20 BALLARI ROCK REGENCY 21 BALLARI MAYURA HOTEL 22 BALLARI KRK RESIDENCY 23 BALLARI VISHNU PRIYA HOTEL 24 BALLARI VIDYA RESIDENCY 25 BALLARI MD SCHOOL 26 BALLARI SIDDHARTH HOTEL 27 BELAGAVI Murarrji Desai School Katkol 28 BELAGAVI Hotel Rajdhani Sankeshwar 29 BELAGAVI New Lodge 30 BELAGAVI CHC Kabbur 31 BELAGAVI Pavan Hotel 32 BELAGAVI CHC Mudalagi 33 BELAGAVI Megha Lodge 34 BELAGAVI APMC Gokak Hostel METRIC NANTAR BALAKIYAR VIDYARTHI 35 BELAGAVI NILAY 36 BELAGAVI Morarji Desai High School Hulikatti 37 BELAGAVI S K LODGE 38 BELAGAVI Classic Lodge Kittur Rani Chennamma Girls Residential 39 BELAGAVI School, Chamakeri Maddi 40 BELAGAVI Priti Lodge Kudachi 41 BELAGAVI Murarji Desai High School Savadatti -

Megalithic Astronomy in South India

In Nakamura, T., Orchiston, W., Sôma, M., and Strom, R. (eds.), 2011. Mapping the Oriental Sky. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Oriental Astronomy. Tokyo, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. Pp. xx-xx. MEGALITHIC ASTRONOMY IN SOUTH INDIA Srikumar M. MENON Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] and Mayank N. VAHIA Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India, and Manipal Advanced Research Group, Manipal University, Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The megalithic monuments of peninsular India, believed to have been erected in the Iron Age (1500BC – 200AD), can be broadly categorized into sepulchral and non-sepulchral in purpose. Though a lot of work has gone into the study of these monuments since Babington first reported megaliths in India in 1823, not much is understood about the knowledge systems extant in the period when these were built – in science and engineering, and especially in mathematics and astronomy. We take a brief look at the archaeological understanding of megaliths, before making a detailed assessment of a group of megaliths in the south Canara region of Karnataka State in South India that were hitherto assumed to be haphazard clusters of menhirs. Our surveys have indicated that there is a positive correlation of sight-lines with sunrise and sunset points on the horizon for both summer and winter solstices. We identify five such monuments in the region and present the survey results for one of these sites, demonstrating their astronomical implications. We also discuss the possible use of megaliths in the form of stone alignments/ avenues as calendar devices. -

Prakrit INT Conference.Cdr

|| Namo Gommat Jinam || || Paaiyam Abbhutthaamo || INVITATION On the occasion of Gommateshwara Bhagawan Shri Shri Shri Bahubali Swami Mahamastakabhisheka Mahotsav 2018 PRAKRIT INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE Date: 3rd November to 6th November 2017 Venue: Shri Nemichandra Siddhantha Chakravarty Sabha Mantap Gommat Nagar, Shravanabelagola, Dist. Hassan (Karnataka) INDIA President of the Conference Prof. Prem Suman Jain, Udaipur * ALL ARE CORDIALLY INVITED * Smt. Sarita M.K. Jain, Chennai Prof. Hampa Nagarajaih, Bengaluru National President Chairman, Reception Committee PIC Prof. Jay Kumar Upadhye, New Delhi Shri S. Jithendra Kumar, Bengaluru Chief Conveners PIC Working President Prof. Rishab Chand Jain, Vaishali Shri Satish Chand Jain (SCJ), New Delhi Prof. Kamal Kumar Jain, Pune General Secretary Conveners PIC Shri Vinod Doddanavar Dr. Priya Darshana Jain, Chennai Secretary and Sammelana incharge Dr. C. P. Kusuma, Shravanabelagola Belagavi Co-Convener PIC R.S.V.P. CHIEF SECRETARY-SDJMIMC TRUST (R) GBMMC-2018, WORKING PRESIDENT-BAHUBALI PRAKRIT VIDYAPEETH (R) Shravanabelagola, Hassan District.Karnataka State HOLY PRESENCE Parama Poojya Charitrachakravarthi Acharya Shri Shri 108 Shantisagar Maharaja's Successor Pancham Pattadisha Vatsalya Varidhi P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Vardhaman Sagar Maharaj and Tyagis of their group. Initiated by : P.P. Acharyashri Shri 108 Parshvasagar Maharaj P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Vasupoojya Sagar Maharaj and Tyagis of their group. Initiated by: P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Bharat Sagar Maharaj P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Panchakalyanak Sagar Maharaj and Tyagis of their group. Initiated by: P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Sanmati Sagar Maharaj P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Chandraprabha Sagar Maharaj and Tyagis of their group. Initiated by: P.P.Acharya Shri Shri 108 Dharmasagar Maharaj P.P.Prajnashraman Balayogi Munishri 108 Amit Sagar Maharaj and Tyagis of their group. -

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World

three ways to be alien Travails & Encounters in the Early Modern World Sanjay Subrahmanyam Subrahmanyam_coverfront7.indd 1 2/9/11 9:28:33 AM Three Ways to Be Alien • The Menahem Stern Jerusalem Lectures Sponsored by the Historical Society of Israel and published for Brandeis University Press by University Press of New England Editorial Board: Prof. Yosef Kaplan, Senior Editor, Department of the History of the Jewish People, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, former Chairman of the Historical Society of Israel Prof. Michael Heyd, Department of History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, former Chairman of the Historical Society of Israel Prof. Shulamit Shahar, professor emeritus, Department of History, Tel-Aviv University, member of the Board of Directors of the Historical Society of Israel For a complete list of books in this series, please visit www.upne.com Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World Jürgen Kocka, Civil Society and Dictatorship in Modern German History Heinz Schilling, Early Modern European Civilization and Its Political and Cultural Dynamism Brian Stock, Ethics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western Culture Fergus Millar, The Roman Republic in Political Thought Peter Brown, Poverty and Leadership in the Later Roman Empire Anthony D. Smith, The Nation in History: Historiographical Debates about Ethnicity and Nationalism Carlo Ginzburg, History Rhetoric, and Proof Three Ways to Be Alien Travails & Encounters • in the Early Modern World Sanjay Subrahmanyam Brandeis The University Menahem Press Stern Jerusalem Lectures Historical Society of Israel Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts For Ashok Yeshwant Kotwal Brandeis University Press / Historical Society of Israel An imprint of University Press of New England www.upne.com © 2011 Historical Society of Israel All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed and typeset in Arno Pro by Michelle Grald University Press of New England is a member of the Green Press Initiative.