Sahyadri Conservation Series 40 Ramachandra T.V. Subash Chandran M.D. Joshi N.V. Prakash Mesta ENVIS Technical Report: 70 Socio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Circle Cycle III Vide Notification R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE CYCLE-III/2020 DATED at BENGALURU-560001, the 21-12-2020

Selection list of Gramin Dak Sevak for Karnataka circle Cycle III vide Notification R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE CYCLE-III/2020 DATED AT BENGALURU-560001, THE 21-12-2020 S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ EWS 1 DR1786DA234B73 MONU KUMAR- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (95)-UR-EWS 2 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR3F414F94DC77 MEGHANA M- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (95.84)-OBC 3 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ ST 1 DR774D4834C4BA HARSHA H M- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (93.12)-ST 4 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ ST 1 DR8DDF4C1EB635 PRABHU- (95.84)- East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak ST Karanth Karanth Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 5 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ UR 2 DR5E174CAFDDE SACHIN ADIVEPPA East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak F HAROGOPPA- Karanth Karanth (94.08)-UR Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 6 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ UR 2 DR849944F54529 SHANTHKUMAR B- East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak (94.08)-UR Karanth Karanth Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 7 Bangalore Bangalore H.K.P. Road H.K.P. Road GDS ABPM/ SC 1 DR873E54C26615 AJAY- (95)-SC East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak 8 Bangalore Bangalore HORAMAVU HORAMAVU GDS ABPM/ SC 1 DR23DCD1262A44 KRISHNA POL- East GPO Dak Sevak (93.92)-SC 9 Bangalore Bangalore Kalyananagar Banaswadi GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR58C945D22D77 JAYANTH H S- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (97.6)-OBC 10 Bangalore Bangalore Kalyananagar Kalyananagar GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR83E4F8781D9A MAMATHA S- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (96.32)-OBC 11 Bangalore Bangalore Kalyananagar Kalyananagar GDS ABPM/ UR 1 DR26EE624216A1 DHANYATA S East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak NAYAK- (95.8)-UR 12 Bangalore Bangalore St. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar in the Court of Sri

10-12-2020 Principal District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar In the Court of Sri C. Rajasekhara, Prl. District & Sessions Judge, U.K. Karwar Cause List Dated:10-12-2020 ARGUMENTS/FDT/CUSTODY/VC/PHYSICAL APPEARANCE (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 1 SC 9/2010 2 SC 37/2013 3 SC 47/2014 4 SC 13/2015 5 SC 32/2019 6 SC 38/2019 7 SC 14/2020 8 SC 16/2020 9 SC 21/2020 10 SC 22/2020 HEARING CASES (MORNING SESSION) 11 Crl.A. 103/2006 12 Crl.A. 154/2006 13 Crl.A. 203/2007 14 Crl.A. 237/2007 15 Crl.A. 114/2008 16 Crl.Misc. 325/2020 17 Crl.Misc. 331/2020 18 Crl.Misc. 353/2020 19 Ankola PS 54/2020 20 Dandeli PS 93/2020 HEARING CASES (AFTERNOON SESSION) 21 Spl.C. 30/2014 22 Spl.C. 47/2019 Page 1 10-12-2020 23 Crl.A. 58/2009 24 Crl.A. 142/2009 25 Crl.R.P. 29/2020 26 Crl.R.P. 54/2020 27 RA 12/2002 28 RA 13/2002 29 RA 2/2006 30 RA 34/2015 31 Misc 47/2020 32 KID 3/2017 33 KID 6/2018 34 KID 8/2019 35 KID 9/2019 36 KID Appln. 1/2018 37 KID Ref. 5/2019 ORDERS ON IA / JUDGMENT 38 Crl.Misc. 312/2020 39 Crl.Misc. 320/2020 40 Crl.Misc. 322/2020 Page 2 PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE COURT, U.K KARWAR Sri C. RAJASEKHARA PRL. DISTRICT SESSIONS JUDGE, COURT U.K, KARWAR Cause List Date: 10-12-2020 Sr. -

Uttara Kannada.Xlsx

Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary services Details of Hospital Co-ordinates to be submitted to AH&VS Helpline District name : Uttar Kannada SL. Taluk Name of the Hospital (VH, VD, Name of the Contact NO Name PVC) Doctor Number 1 Ankola VHAnkola DR KM Hegde 9449753809 https://goo.gl/maps/22GmJB6u4hR8ns197 2 Ankola VD Harwada Dr. Deepk S.J. 7760748474 not available 3 Ankola VD Agsur Dr. Chaitra D. 9743120463 https://goo.gl/maps/qpTBQZti38ur2X7v5 4 Ankola VD Ramanguli Dr. Chaitra D. 9743120463 https://goo.gl/maps/Xtfm7AYgWUa2jXRz5 5 Ankola VD Hillur Dr. Chandan R. 9731127674 https://goo.gl/maps/7Q855hfC5Sn6fyfs6 6 Ankola VD Adigona Dr. Deepk S.J. 7760748474 https://goo.gl/maps/Ltwy6tFBSUxo4Phw8 7 Ankola VD Halvalli Dr. Chandan R. 9731127674 8 Ankola VD Basgod Dr. Deepk S.J. 7760748474 https://goo.gl/maps/obLgGkVDvh1i3NhF9 9 Ankola VD Kodalgadde Dr. Chandan R. 9731127674 https://goo.gl/maps/SUN5we14t72NA5qo9 10 Bhatkal VH Bhatkal Dr. V.L. Hegde 9449053634 https://goo.gl/maps/qVP8PrxPAcrcQbcZ7 11 Bhatkal VD Murdeshwar Dr. V.L. Hegde 9449053634 https://goo.gl/maps/Z2iAtaheS9fQsTsG8 12 Bhatkal VD Bailur Dr. V.L. Hegde 9449053634 https://goo.gl/maps/kZ9RLWk9KKCptYuS9 13 Bhatkal VD Bengre Dr. V.L. Hegde 9449053634 https://goo.gl/maps/8UuyorvfnG1wvSky9 14 Bhatkal VD Katgarkoppa Dr. V.L. Hegde 9449053634 https://goo.gl/maps/YS9BZV2smNtmZV78A 15 Bhatkal VD Kuntvani Dr. V.L. Hegde 9449053634 https://goo.gl/maps/1doZbG13od9751yX9 16 Haliyal VH Haliyal Dr. K.M. Nadaf 9845806840 https://goo.gl/maps/PKqF41Txx7CCbXwKA 17 Haliyal VD Tergaon Dr. K.M. Nadaf 9845806840 https://goo.gl/maps/L4vA7CdLxXTCTLrr5 18 Haliyal VH Murkwada Dr. -

District Irrigation Plan (Dip)

DISTRICT IRRIGATION PLAN (DIP) UTTARAKANNADA DISTRICT KARNATAKA STATE 1 | D I P U K Index Sl no Contents Page NO 1 Introduction 6-7 Components and responsible Ministries /Departments 8-9 District Irrigation Plans (DIPs ) 10 Background 11 Vision and Objective 12 Strategy /Approach 13 Methodology 14 Rationale/Justification statement 15-16 2 CHAPTER -1 General Information district 1.1 District Profile 17 1.2 Brief History of the district 20-24 1.3 Present administrative Profile 24 1.4 Demography 25 1.5 Biomass and Livestock 27 1.6 Agro, Ecology, Climate, Hydrdogy, and topography 28-29 1.7 Land use pattern in uttarakannda 31 1.8 Soil Profile 35 1.9 Soil Erosion and Run off status 41 1.10 Rail Fall 42 1.11 Ground water 43 2 | D I P U K 3 CHAPTER -2 District water Profile 2.1 Area wise, Crop wise irrigation status 50 2.2 Production and productivity of major crops 53 2.3 Irrigation based classification 54 4 CHAPTER -3 3.1 Status of water availability 55 3.2 Status of ground water Availability 56 3.3 Existing type of irrigation 58 5 CHAPTER -4 Water Requirement demand 4.1 Domestic water 59 4.2 Crop water requirement 60 4.3 Livestock water demand 65 4.4 Industrials water demand 66 4.5 Water demand of power generation 67 4.6 Total water demand (Present) of district for various sectors 68 4.6 a Total water Demand of the District for various sectors 69 4.7 Water Budget 70 3 | D I P U K Index Sl no Contents (Table) Page No 1 1.1 District Profile 18 2 1.5 Biomass and Live stock 27 3 1.6 Agro, Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and topography 30 4 1.7 -

A Study of Regional Organization at Banavasi, C. 1 St

Complexity on the Periphery: A study of regional organization at Banavasi, c. 1st – 18th century A.D. by Uthara Suvrathan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Carla Sinopoli, Chair Emeritus Professor Thomas R. Trautmann Professor Henry T. Wright Emeritus Professor Norman Yoffee © Uthara Suvrathan 2013 Dedication For Amma and Acha ii Acknowledgements I have been shaped by many wonderful scholars and teachers. I would first like to thank Carla Sinopoli for the mentorship she has given me throughout my time in Graduate school, and even earlier, from that steep climb up to Kadebakele and my very first excavation. She has read several drafts of this dissertation and discussions with her always strengthened my research. My dissertation was greatly enriched by comments from my other committee members. Chats with Henry Wright left me filled with new ideas. Norm Yoffee’s long-distance comments were always thought provoking. Tom Trautmann’s insights never failed to suggest new lines of thought. Although not committee members, I would also like to thank Dr. Upinder Singh for initiating my love of all things ‘Ancient’, Dr. H. P. Ray for fostering my interest in archaeology, and Dr. Lisa Young for giving me opportunities to teach. My field work in India was made possible by grants from the National Science Foundation, Rackham Graduate School, the Museum of Anthropology and the Trehan Foundation supporting South Asian Research at the University of Michigan. I would especially like to thank the American Institute of Indian Studies, and Dr. -

District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar in the Court of Sri

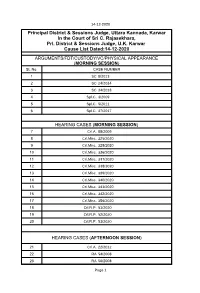

14-12-2020 Principal District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar In the Court of Sri C. Rajasekhara, Prl. District & Sessions Judge, U.K. Karwar Cause List Dated:14-12-2020 ARGUMENTS/FDT/CUSTODY/VC/PHYSICAL APPEARANCE (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 1 SC 8/2013 2 SC 24/2014 3 SC 34/2018 4 Spl.C. 3/2009 5 Spl.C. 5/2011 6 Spl.C. 37/2017 HEARING CASES (MORNING SESSION) 7 Crl.A. 88/2009 8 Crl.Misc. 325/2020 9 Crl.Misc. 328/2020 10 Crl.Misc. 336/2020 11 Crl.Misc. 337/2020 12 Crl.Misc. 338/2020 13 Crl.Misc. 339/2020 14 Crl.Misc. 340/2020 15 Crl.Misc. 341/2020 16 Crl.Misc. 342/2020 17 Crl.Misc. 356/2020 18 Crl.R.P. 51/2020 19 Crl.R.P. 52/2020 20 Crl.R.P. 53/2020 HEARING CASES (AFTERNOON SESSION) 21 Crl.A. 22/2012 22 RA 54/2008 23 RA 56/2008 Page 1 14-12-2020 24 RA 80/2008 25 RA 7/2012 26 Misc 48/2020 27 Misc 49/2020 28 Misc 50/2020 29 Misc 51/2020 30 KID 1/2017 31 KID 2/2017 32 KID 5/2018 33 KID 7/2018 34 KID 8/2018 35 KID 9/2018 36 KID 1/2019 37 KID 2/2019 ORDERS ON IA / JUDGMENT 38 Crl.Misc. 321/2020 39 Crl.Misc. 326/2020 40 Crl.Misc. 334/2020 Page 2 PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE COURT, U.K KARWAR Sri C. RAJASEKHARA PRL. DISTRICT SESSIONS JUDGE, COURT U.K, KARWAR Cause List Date: 14-12-2020 Sr. -

02-12-2020 Page 1

02-12-2020 Principal District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar In the Court of Sri C. Rajasekhara, Prl. District & Sessions Judge, U.K. Karwar CauseList Dated:02-12-2020 ARGUMENTS/FDT/CUSTODY/VC/PHYSICAL APPEARANCE (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 1 SC 37/2013 2 SC 59/2013 3 SC 68/2013 4 SC 18/2014 5 SC 3/2015 6 SC 15/2015 7 SC 24/2015 8 SC 6/2020 9 SC 23/2020 10 SC 25/2020 11 SC 27/2020 12 SC 28/2020 HEARING CASES (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 13 Crl.A. 78/2006 14 Crl.A. 154/2006 15 Crl.Misc. 324/2020 16 Crl.Misc. 325/2020 17 Crl.Misc. 326/2020 18 Gokarna PS 74/2020 19 Gokarna PS 75/2020 20 Ankola PS 54/2020 HEARING CASES (AFTERNOON SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 21 Crl.A. 140/2008 22 Crl.A. 149/2008 23 Crl.R.P. 11/2017 24 Crl.R.P. 42/2017 25 Crl.R.P. 48/2020 26 Crl.R.P. 50/2020 27 Kumta PS Cr. 131/2020 28 RA 59/2006 29 RA 74/2007 30 RA 30/2014 31 RA 31/2014 32 RA 28/2015 33 RA 40/2015 34 MA 6/2020 35 MA 7/2020 36 MA 8/2020 37 MA 9/2020 38 MA 10/2020 39 MA 11/2020 ORDERS ON IA / JUDGMENT SL.No. CASE NUMBER 40 SC 25/2018 Page 1 PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE COURT, U.K KARWAR Sri C. RAJASEKHARA PRL. -

District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar in the Court of Sri

04-12-2020 Principal District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar In the Court of Sri C. Rajasekhara, Prl. District & Sessions Judge, U.K. Karwar Cause List Dated:04-12-2020 ARGUMENTS/FDT/CUSTODY/VC/PHYSICAL APPEARANCE (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 1 SC 2/2017 2 SC 5/2017 3 SC 9/2017 4 SC 36/2018 5 SC 10/2019 6 SC 14/2019 7 SC 3/2020 8 SC 10/2020 9 Spl.C. 5/2011 HEARING CASES (MORNING SESSION) 10 Crl.A. 151/2008 11 Crl.A. 155/2008 12 Crl.Misc. 305/2020 13 Crl.Misc. 314/2020 14 Crl.Misc. 319/2020 15 Crl.Misc. 321/2020 16 Crl.Misc. 326/2020 17 Crl.Misc. 327/2020 18 Crl.Misc. 330/2020 19 Crl.Misc. 332/2020 20 Crl.Misc. 333/2020 HEARING CASES (AFTERNOON SESSION) 21 Crl.R.P. 157/2015 22 Crl.R.P. 129/2016 23 Crl.R.P. 117/2017 24 Crl.R.P. 115/2019 25 Crl.R.P. 17/2020 26 Crl.R.P. 39/2020 27 Crl.R.P. 41/2020 28 Crl.R.P. 46/2020 29 RA 2/2006 30 RA 58/2006 31 RA 85/2006 32 RA 421/2009 33 RA 44/2014 34 RA 21/2015 Page 1 04-12-2020 35 RA 13/2020 36 RA 14/2020 37 MC 8/2020 38 KID(Ref) 8/2020 39 KID(Ref) 9/2020 ORDERS ON IA / JUDGMENT 40 Karwar CEN Cr. 26/2020 Page 2 PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE COURT, U.K KARWAR Sri C. -

District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar in the Court of Sri

Sheet1 Principal District & Sessions Judge, Uttara Kannada, Karwar In the Court of Sri C. Rajasekhara, Prl. District & Sessions Judge, U.K. Karwar Cause List Dated:05-12-2020 ARGUMENTS/FDT/CUSTODY/VC/PHYSICAL APPEARANCE (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 1 SC 6/2017 2 SC 13/2020 3 SC 20/2020 4 Spl.C. 3/2010 5 Spl.C. 20/2011 6 Spl.C. 76/2020 7 Spl.C. 126/2020 8 Crl.A. 176/2007 9 Crl.Misc. 280/2020 10 Crl.Misc. 322/2020 11 Crl.Misc. 334/2020 12 Crl.Misc. 335/2020 13 Crl.Misc. 340/2020 14 Crl.Misc. 341/2020 15 Crl.Misc. 342/2020 16 Crl.Misc. 343/2020 HEARING CASES (MORNING SESSION) SL.No. CASE NUMBER 17 Misc. 36/2014 18 Misc. 30/2020 19 MA 13/2020 20 P & SC 5/2020 Page 1 PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE COURT, U.K KARWAR Sri C. RAJASEKHARA PRL. DISTRICT SESSIONS JUDGE, COURT U.K, KARWAR Cause List Date: 05-12-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 02:45-05:00 PM 1 M.C. 6/2020 Kedar Nagesh Nayak PARAMESHWAR (HEARING) Vs SHRIKRISHNA IA/1/2020 Shruti Panduranga Shanbhag BHAT wife of Kedar Nayak 2 R.A. 6/2020 M/S.Sanjay Prabhu a proprietary RAMANATH (FOR FURTHER STEPS) concern Rep. by its proprietor VAMAN BHAT IA/1/2020 Sanjay M. Prabhu Vs Managing Director, Raghunath Mitthal Janki Corp Limited 3 R.A. 12/2020 Prasanna Prakash Shet K.R. Desai (Awaiting Records) Vs Amita Deepak Shenvi 11:00-01:30 AM 4 M.A. -

NOTIFICATION for the POSTS of GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – III/2020-2021 KARNATAKA CIRCLE Applications Are Invited by the Respect

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – III/2020-2021 KARNATAKA CIRCLE R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE CYCLE-III/2020 DATED AT BENGALURU-560001, THE 21-12-2020 Applications are invited by the respective engaging authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone/laptop supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device/laptop/equipment ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the Branch Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same Branch Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM and other Supervising authorities. -

Dealer Details 04/07/2014

Dealer Details 04/07/2014 State Name District Name Agency Name Dealer Id Mobile Dealer Type Karnataka Uttara Kannada HALIYAL T A P C M S LTD 211575 9980113218 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada KUMARESHWARA KRISHI KENDRA 211581 9448774793 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada AJJIBAL S S SANGH 211589 9448527334 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada VSSSN BANAVASI 211592 9482986331 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada TAPCMS SIRSI 211662 9449628385 WHOLESALER Karnataka Uttara Kannada KSCMF SIRSI 211664 9449864430 WHOLESALER Karnataka Uttara Kannada JANATA AGRO KENDRA 211745 9449708011 WHOLESALER Karnataka Uttara Kannada JANATA AGRO KENDRA 212014 9449708011 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada TAPCMS ANKOLA 212183 9448317763 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada P G KERUDI 212893 9448631109 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada KELAGINUR VSSSN 215000 9972711743 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada K.S.C.M.F. SIRSI 215007 9449864430 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada SHRI SHAKTI ENTERPRISES 220610 8277006927 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada T A P C M S SIRSI 220611 9449628385 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada TOTAGARS CO-OP SALE SOCIETY LT 220612 9008966764 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada VSSNB KELAGINOOR 220613 8762786837 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada PAVAN AGENCIES 220614 9448575754 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada NAYAK TRADERS 220615 9901653877 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada MADHUKAR ANANDU PAI and BRO 220616 9448575922 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada MAHALASA TRADERS 220617 9480603707 RETAILER Karnataka Uttara Kannada YAJI AGRO CENTRE 220618 8762202402