The Reality Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Developer Index 2010 Foreword

SWEDISH GAME INDUSTRY’S REPORTS 2011 Game Developer Index 2010 Foreword It’s hard to imagine an industry where change is so rapid as in the games industry. Just a few years ago massive online games like World of Warcraft dominated, then came the breakthrough for party games like Singstar and Guitar Hero. Three years ago, Nintendo turned the gaming world upside-down with the Wii and motion controls, and shortly thereafter came the Facebook games and Farmville which garnered over 100 million users. Today, apps for both the iPhone and Android dominate the evolution. Technology, business models, game design and marketing changing almost every year, and above all the public seem to quickly embrace and follow all these trends. Where will tomorrow’s earnings come from? How can one make even better games for the new platforms? How will the relationship between creator and audience change? These and many other issues are discussed intensively at conferences, forums and in specialist press. Swedish success isn’t lacking in the new channels, with Minecraft’s unprecedented success or Battlefield Heroes to name two examples. Independent Games Festival in San Francisco has had Swedish winners for four consecutive years and most recently we won eight out of 22 prizes. It has been touted for two decades that digital distribution would outsell traditional box sales and it looks like that shift is finally happening. Although approximately 85% of sales still goes through physical channels, there is now a decline for the first time since one began tracking data. The transformation of games as a product to games as a service seems to be here. -

Battlefield 3 Online Cracked Server

Battlefield 3 online cracked server click here to download Heute mal ein Tutorial von mir ich hoffe es Gefällt euch habe ich durch zufalle gefunden diese. PCMASTER How to play Battlefield 3 Multiplayer Crack in the Pirated Version with % DLC! [ZLOGAMES. (NEW/UPDATED) How To Play Battlefield 3 Multiplayer For Free! . The servers you can play are they only. Searching: Battlefield 3 Servers Remove BF3, [HCM] HardcoreMedics Mixed CQL 24/7 | Infantry-friendly server, 54/64, , Caspian Border.Search Bf3 Stats, Rankings · Search Bf3 · Fast Respawn | Rank Cap | [SKL]. Both server's are Cracked so you do not need a legit copy of the game to play Continue from here if you just copied your Battlefield 3 folder. Heey guys, i heard from freidns there is a BF3 Cracked mulitplayer server. i mean that you can download for free. i just wanted to know it is real, [Solved] Battlefield 4 cracked multiplayer servers. Battlefield 3 Multiplayer Cracked with All DLC and Premium (Tested and 3 servers with ability to include all DLCs with Premium BF3. By the way, My freind has an original bf 3 which is connected with origin, is it possible if i can invite him with me to play on a cracked server. Battlefield 3 has gotten a new mod that may breath new life into it. It's been years since the release of Battlefield 3, and a bit less since th. You have to maximise it and wait to connect to the server. Note: Join servers with as low as possible How. Its just theres so many people claiming to have cracked it, and people But a simply google: bf3 no origin' shows many legitimate sites Venice Unleashed!(Battlefield 3 server emulator). -

Parham Gholami

June 29th, 2015 Re: Docket No. 2014-7 Exemptions to Prohibition Against Circumvention of Technological Measures Protecting Copyrighted Works Dear Ms. Charlesworth, Thank you for giving me the opportunity to take part in the hearing regarding Class 23. The following is my response to your post-hearing questions. 1. Please explain whether, and under what circumstances, video game publishers reissue or repackage games where the publisher or developer has previously ended support for a server that enables single-player and/or multiplayer play. Please provide illustrative examples, including an explanation of the similarities and differences between the original and reissued products and the role of technological protection measures. How frequently does this occur? Several games being sold today have effectively been digitally reissued and no longer have the core online multiplayer functionality available to the customer. Nintendo’s Mario Kart DS (2005), as discussed during the public hearing, was re-released for purchase on the Nintendo Wii U on April 23rd, 2015 through their online marketplace (Nintendo eShop). The menus to access the game’s multiplayer features that use the Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection, Nintendo’s online multiplayer service, are fully visible within the game. However, trying to access them spits out a generic error that, when searched online, only states that the game console was not able to successfully connect to the internet. In truth, the user cannot play online because the Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection has been discontinued since May 20th, 2014. Despite this being a significant component of the game, nowhere on either Nintendo’s eShop website1 or within the Wii U’s eShop listing does Nintendo acknowledge that the game’s online multiplayer has been discontinued. -

Stevens, RC and Raybould, D (2015) the Reality Paradox: Authenticity, fidelity, and the Real in Battle- field 4

Citation: Stevens, RC and Raybould, D (2015) The reality paradox: Authenticity, fidelity, and the real in Battle- field 4. The Soundtrack, 8 (1-2). 57 - 75. ISSN 1751-4207 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/st.8.1-2.57_1 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/2216/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. The Reality Paradox: Authenticity, fidelity and the real in Battlefield 4 Richard Stevens and Dave Raybould, with additional contributions from Ben Minto, Audio Director Battlefield 4.1 Although the interactive medium of video games is often referred to as non-linear, since progression through the game may follow different paths on repeated playthroughs, it is typically much more linear than the medium of film with respect to its treatment of time and space. -

Troubleshooting Guide

TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE Solved - Issue with USB devices after Windows 10 update KB4074588 Logitech is aware of a Microsoft update (OS Build 16299.248) which is reported to affect USB support on Windows 10 computers. Support statement from Microsoft "After installing the February 13, 2018 security update, KB4074588 (OS Build 16299.248), some USB devices and onboard devices, such as a built-in laptop camera, keyboard or mouse, may stop working for some users." If you are using Microsoft Windows 10, (OS Build 16299.248) and are having USB-related issues. Microsoft has released a new update KB4090913 (OS Build 16299.251) to resolve this issue. We recommend you follow Microsoft Support recommendations and install the latest Microsoft Windows 10 update: https://support.microsoft.com/en-gb/help/4090913/march5- 2018kb4090913osbuild16299-251. This update was released by Microsoft on March 5th in order to address the USB connection issues and should be downloaded and installed automatically using Windows Update. For instructions on installing the latest Microsoft update, please see below: If you have a working keyboard/mouse If you have a non-working keyboard/mouse If you have a working keyboard/mouse: 1. Download the latest Windows update from Microsoft. 2. If your operating system is 86x-based, click on the second option. If your operating system is 64x-based, click on the third option. 3. Once you have downloaded the update, double-click on the downloaded file and follow the on-screen instructions to complete the update installation. NOTE: If you wish to install the update manually, you can download the 86x and 64x versions of the update from http://www.catalog.update.microsoft.com/Search.aspx?q=KB4090913 If you currently have no working keyboard/mouse: For more information, see the Microsoft article on how to start and use the Windows 10 Recovery Environment (WinRE): https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/help/4091240/usb-devices-may-stop-working-after- installing-the-february-13-2018-upd Do the following: 1. -

Where Do Game Design Ideas Come From? Invention and Recycling in Games Developed in Sweden Ulf Hagen Södertörns University 141 89 Huddinge, Sweden [email protected]

Where Do Game Design Ideas Come From? Invention and Recycling in Games Developed in Sweden Ulf Hagen Södertörns University 141 89 Huddinge, Sweden [email protected] ABSTRACT sequels and licensed games. In this paper I will try to The game industry is often accused for not being original contribute to the discussion by examining the design ideas and inventive enough, making sequels and transmediations behind the games. instead of creating new game concepts and genres. Idea creation in game development has not been studied much In media studies many scholars have observed that the by scholars. This paper explores the origin of game design media landscape of today is characterized by a flow of ideas, with the purpose of creating a classification of the content in between different media forms and individual domains the ideas are drawn from. Design ideas in 25 works. Intertextuality and transmediation are terms that games, developed by the four main game developers in describe aspects of this phenomenon, which Jenkins [11] Sweden, have been collected mainly through interviews sees as a sign of a “convergence culture”. Bolter & Grusin’s with the designers and through artifact analyses of the [3] concept remediation describes how not only content, but games. A grounded theory approach was then used to also representational approaches and styles are used, develop categories “bottom-up” from the collected data. borrowed, reshaped, adapted, and recycled all over the This resulted in four main categories and a number of sub media landscape. They even propose that in contemporary categories, describing different domains that game design culture “all mediation is remediation” [3]. -

Game Developer Index 2011 Swedish Games Industry’S Reports 2012

GAME DEVELOPER INDEX 2011 SWEDISH GAMES INDUSTRY’S REPORTS 2012 Pic: Sacred Citadel (in development), Southend Interactive TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 YEAR OF REGISTRY 12 WORDLIST 3 GAME DEVELOPER MAP 13 FOREWORD 4 REVENUES OF FREE-TO-PLAY 14 Example 14 TURNOVER AND PROFIT 5 CPM 15 eCPM 15 NUMBER OF COMPANIES 7 NEW SERVICES, NEW PIRACY 15 NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES 7 THE VALUE CHAIN 16 GENDER DISTRIBUTION 8 FUTURE 16 TURNOVER PER COMPANY 8 WORLDWIDE 17 EMPLOYEES PER COMPANY 8 International Expansions 18 BIGGEST PLAYERS 8 GAME SALES 19 DISTRIBUTION PLATFORMS 8 AVERAGE REVIEW SCORES 20 New Technology 9 Cloud Gaming 10 INNOVATIONS IN MARKETING 21 Outsourcing/Consulting 10 Specialized Subcontractors 11 CONCLUSION 22 DLC 11 METHOD 22 LOCATION OF COMPANIES 12 1 | Game Developer Index 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Game Developer Index analyzes Swedish game developers’ activities and international industry trends of the past year by compiling key figures from the respective companies’ annual reports. Swedish game development is an export industry and acts on a highly globalized market. The game industry has in a couple of decades grown from a niche embraced by enthusiasts to a global industry with a considerate cultural and economic impact. Game Developer Index 2011 compiles Swedish game developers’ annual reports for their latest fiscal year. In short: • Swedish game developers nearly double their turnover in 2011, amassing a 96 % growth to a total of 257 million EUR. • The majority (60 %) of companies are profitable and the industry reports a combined profit for the third year in a row. • Employment increases by 26 % to a total of 1 512 employees, also a record breaking number. -

Battlefield 2142 Crack 1.50

Battlefield 2142 crack 1.50 tPORt no CD Battlefield v All. More Battlefield Fixes. Battlefield v All · Battlefield All · Battlefield v All. This was using Battlefield Deluxe and Windows Vista Premium 64bit This method worked for me,, I had. The latest and final patch for Battlefield It adds the you can patch from vanila, just (mb), then (2gb). make sure its the. Battlefield Update This Patch Adds great features and Fixes to the BattleField Game Engine. They just released the update two days ago I was wondering if anyone had found a no-cd for version yet I have checked everywhere I. its been sometime since the patch was released and i think the time has passed regarding the minimum time limit until you can ask for a crack. After a successful open beta phase of Battlefield Update and tweaks and updates being made based on feedback on the forums we. I heard that the BF2 patch allows you to play the game without the disk inserted but I haven't How about BF though? BF can also be found on that site. .. Any nocd cracks will result in punkbuster kicks. bf no cd crack Download Link ?keyword=bfno-cd-crack&charset=utf-8 =========> bf no cd. Battlefield [MULTI15] No- DVD/Fixed Image; Battlefield v [MULTI15] Battlefield v +5 TRAINER; Battlefield v +4 TRAINER. Battlefield Game Fixes, No-CD Game Fixes, No-CD Patches, No-CD Files, PC Game Fixes to enable you to play your PC Games without the CD in the. Ever since EA dropped support for BF, the game gets stuck at the master account logon prompt. -

Advertising in Computer Games

ADVERTISING IN COMPUTER GAMES by Ilya Vedrashko B.A. Business Administration, American University in Bulgaria, 2000 Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2006 Signature of author …………………………………………………………………………. Dept. of Comparative Media Studies, August 11, 2006 Certified by…………………………………………………………………………………. Prof. William Uricchio Accepted by……………………………………………………………………………….... Prof. William Uricchio © 2006 Ilya Vedrashko. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. 1 ADVERTISING IN COMPUTER GAMES by Ilya Vedrashko Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract This paper suggests advertisers should experiment with in-game advertising to gain skills that could become vital in the near future. It compiles, arranges and analyzes the existing body of academic and industry knowledge on advertising and product placement in computer game environments. The medium’s characteristics are compared to other channels’ in terms of their attractiveness to marketers, and the business environment is analyzed to offer recommendations on the relative advantages of in-game advertising. The paper also contains a brief historical review of in-game advertising, and descriptions of currently available and emerging advertising formats. Keywords Advertising, marketing, branding, product placement, branded entertainment, networks, computer games, video games, virtual worlds. -

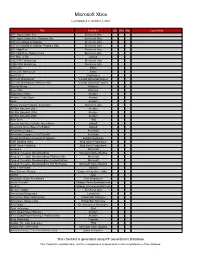

Microsoft Xbox

Microsoft Xbox Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007: Agent Under Fire Electronic Arts 007: Agent Under Fire: Platinum Hits Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing: Platinum Hits Electronic Arts 007: NightFire Electronic Arts 007: NightFire: Platinum Hits Electronic Arts 187 Ride or Die Ubisoft 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2006 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 25 to Life Eidos 25 to Life: Bonus CD Eidos 4x4 EVO 2 GodGames 50 Cent: Bulletproof Vivendi Universal Games 50 Cent: Bulletproof: Platinum Hits Vivendi Universal Games Advent Rising Majesco Aeon Flux Majesco Aggressive Inline Acclaim Airforce Delta Storm Konami Alias Acclaim Aliens Versus Predator: Extinction Electronic Arts All-Star Baseball 2003 Acclaim All-Star Baseball 2004 Acclaim All-Star Baseball 2005 Acclaim Alter Echo THQ America's Army: Rise of a Soldier: Special Edition Ubisoft America's Army: Rise of a Soldier Ubisoft American Chopper Activision American Chopper 2: Full Throttle Activision American McGee Presents Scrapland Enlight Interactive AMF Bowling 2004 Mud Duck Productions AMF Xtreme Bowling Mud Duck Productions Amped 2 Microsoft Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding Microsoft Game Studios Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding: Platinum Hits Microsoft Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding: Limited Edition Microsoft Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding: Not for Resale Microsoft Game Studios AND 1 Streetball UbiSoft Antz Extreme Racing Empire Interactive / Light... APEX Atari Aquaman: Battle For Atlantis TDK -

Pico-8 Special Pixel Perfect Make Your First Game in Modern Games Made with a Tiny Virtual Console Retro Constraints

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES PICO-8 SPECIAL PIXEL PERFECT MAKE YOUR FIRST GAME IN MODERN GAMES MADE WITH A TINY VIRTUAL CONSOLE RETRO CONSTRAINTS Issue 12 £3 wfmag.cc 12 72000 16 7263 97 REBELREBEL INSIDE THE GENRE-REDEFINING RHYTHM GAME, NO STRAIGHT ROADS Subscribe today 13 issues for £20 Visit wfmag.cc/subscribe or call 01293 312192 to order Subscription queries: [email protected] There’s no such thing as an apolitical game he Division 2 takes place in Washington unabashedly celebrate empire in all its forms, like ‘Tar of D.C. in the aftermath of a smallpox All Weathers, or the Game of British Colonies’ (c.1857). pandemic, and has you liberating the city They’re statements, whether the designer perceived T from a corrupt government. The game’s them as such or not. If I came across a source stating tone-deaf marketing used real-world political tensions, that one of the publishers of these games denied its such as sending out a joke email referencing the US game was a comment on empire, then my reaction HOLLY NIELSEN government shutdown and a spoof letter declaring wouldn’t be ‘Well, I guess I can’t analyse it because it’s Mexico ‘approved funding for building a wall along the Holly Nielsen is a not a statement after all’. If anything, it would pique videogame journalist United States border’. and historian who my interest, because the idea that structured games Despite all this, creative director Terry Spier recently researches the are purely escapist fun is a fairly modern concept. -

Observing the International

OBSERVING THE INTERNATIONAL: GOVERNMENTALITY OF GEOPOLITICS, VISUAL CULTURE AND THE SOCIAL LOGISTICS OF WAR MAKING M. Evren EKEN PhD Thesis Royal Holloway, University of London April 2018 Declaration of Authorship The title page should be followed by a signed declaration that the work presented in the thesis is the candidate’s own. Please note that there is no set wording for this but an example is provided below: Declaration of Authorship I ……………………. (please insert name) hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ Abstract: It is common in International Relations to read that “war made states and states made war”. Despite a growing literature on the relationship between visual culture and geopolitics, there is a gap around the manner in which war-making ability of states is dependent upon the population and the conduct of geopolitical subjects. This doctoral thesis interrogates the ways in which the mainstream US visual culture structures the possible field of geopolitical actions and imaginations of the population during the Global War on Terror (GWoT) to understand and explain why this gap matters. It analyses how visual culture encapsulates the population as an affective interpretative repertoire and is conducive to the war-making ability of the US. The project contributes to academic literatures on `Governmentality Studies`, `Critical Geopolitics`, `Critical Military Studies`, `Visual Culture ` and `the Sociology of the State` and offers a framework for making sense of the relationship between visual culture, war-making and governmentality.