Church and Graveyard Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603. Coral Georgina Stoakes, Sidney Sussex College, December, 2016. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. At 79,339 words it does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the History Degree Committee. Abstract Early modern English Catholic eschatology, the belief that the present was the last age and an associated concern with mankind’s destiny, has been overlooked in the historiography. Historians have established that early modern Protestants had an eschatological understanding of the present. This thesis seeks to balance the picture and the sources indicate that there was an early modern English Catholic counter narrative. This thesis suggests that the Catholic eschatological understanding of contemporary events affected political action. It investigates early modern English Catholic eschatology in the context of proscription and persecution of Catholicism between 1558 and 1603. -

The Seaxe Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society

The Seaxe Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society Editor – Stephen Kibbey, 3 Cleveland Court, Kent Avenue, Ealing, London, W13 8BJ (Telephone: 020 8998 5580 – e-mail: [email protected]) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… No.56 Founded 1976 September 2009 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Queen Charlotte’s Hatchment returns to Kew. Photo: S. Kibbey Peach Froggatt and the restored Queen Charlotte‟s Hatchment in Kew Palace. Late afternoon on Thursday 23rd July 2009 a small drinks party was held at Kew Palace in honour of Peach Froggatt, one of our longest serving members. As described below in Peach‟s own words, the hatchment for Queen Charlotte, King George III‟s wife, was rescued from a skip after being thrown out by the vicar of St Anne‟s Church on Kew Green during renovation works. Today it is back in the house where 191 years ago it was hung out on the front elevation to tell all visitors that the house was in mourning. “One pleasant summer afternoon in 1982 when we were recording the “Funeral Hatchments” for Peter Summers “Hatchments in Britain Series” we arrived at Kew Church, it was our last church for the day. The church was open and ladies of the parish were busy polishing and arranging flowers, and after introducing ourselves we settled down to our task. Later the lady in charge said she had to keep an appointment so would we lock up and put the keys through her letterbox. After much checking and photographing we made a thorough search of the church as two of the large hatchments were missing. Not having any luck we locked the church and I left my husband relaxing on a seat on Kew Green while I returned the keys. -

Guide to BOWDON PARISH CHURCH and the SURROUNDING AREA

Guide to BOWDON PARISH CHURCH and the SURROUNDING AREA FREE i An Ancient Church and Parish Welcome to Bowdon and the Parish The long ridge of Bowdon Hill is crossed by the Roman road of Watling Street, now forming some of the A56 which links Cheshire and Lancashire. Church of St Mary the Virgin Just off this route in the raised centre of Bowdon, a landmark church seen from many miles around has stood since Saxon times. In 669, Church reformer Archbishop Theodore divided the region of Mercia into dioceses and created parishes. It is likely that Bowdon An Ancient Church and Parish 1 was one of the first, with a small community here since at least the th The Church Guide 6 7 century. The 1086 Domesday Book tells us that at the time a mill, church and parish priest were at Bogedone (bow-shaped ‘dun’ or hill). Exterior of the Church 23 It was held by a Norman officer, the first Hamon de Massey. The church The Surrounding Area 25 was rebuilt in stone around 1100 in Norman style then again in around 1320 during the reign of Edward II, when a tower was added, along with a new nave and a south aisle. The old church became in part the north aisle. In 1510 at the time of Henry VIII it was partially rebuilt, but the work was not completed. Old Bowdon church with its squat tower and early 19th century rural setting. 1 In 1541 at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the parish was transferred to the Diocese of Chester from the Priory of Birkenhead, which had been founded by local lord Hamon de Massey, 3rd Baron of Dunham. -

Sacred Text—Sacred Space Studies in Religion and the Arts

Sacred Text—Sacred Space Studies in Religion and the Arts Editorial Board James Najarian Boston College Eric Ziolkowski Lafayette College VOLUME 4 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/sart Sacred Text—Sacred Space Architectural, Spiritual and Literary Convergences in England and Wales Edited by Joseph Sterrett and Peter Thomas LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Sacred text, sacred space : architectural, spiritual, and literary convergences in England and Wales / edited by Joseph Sterrett and Peter Thomas. p. cm. — (Studies in religion, ISSN 1877-3192 ; v. 4) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20299-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Christianity and the arts—England— History. 2. Christianity and the arts—Wales—History. I. Sterrett, Joseph. II. Thomas, Peter Wynn. BR744.S23 2011 261.5’70942—dc23 2011034521 ISSN 1877–3192 ISBN 978 90 04 20299 3 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............................................................................. vii List of Illustrations ............................................................................ -

Hawstead Hatchments 2Page Handout.Pdf

1 2 3 4 5 The Hawstead Hatchments from Left to Right 1. FRANCES Jane Metcalfe, died 1830 aged 36. Frances was the first wife of Henry Metcalfe of Hawstead House (his hatchment is no. 4). On the shield, his ‘arms’ are on the left and the background is white, indicating that he is still alive. This contrasts with the right side of the hatchment (his wife’s side) which is black. The coat of arms on her side is that of her ancestral family which is Whish. NB “Resurgam” = “I shall arise again”. 2. SOPHIA Metcalfe, died 1855 aged 66 OR ELLEN Frances Metcalfe, died 1858, aged 70. It is unclear which of these two unmarried sisters of Henry Metcalfe this hatchment commemorates. The absence of the heraldic shield and helmet and the presence of a ribbon at the top, together with the completely black background, indicate that this hatchment is for a deceased spinster. 3. FRANCIS Hammond, died 1727, aged 38. This is the oldest hatchment, and the only one not commemorating a member of the Metcalfe family. The Hammonds lived at “Hammonds” in Bull Lane, Pinford End (a hamlet within Hawstead). Francis was married to Honor Asty and hence his coat of arms, including the birds and a chevron with scallops, is on the left with the Asty arms, two falcons and a diagonal stripe of ermine on a red background, to the right. The fact that the background is completely black indicates that the hatchment was made in 1758 after she died. NB “Mors janum vitae” = “Death is the doorway to life”. -

Information for Tour Guides About the Grote Kerk in Monnickendam

INFORMATION FOR TOUR GUIDES ABOUT THE GROTE KERK IN MONNICKENDAM THE HISTORY OF THE GROTE KERK OR SAINT NICHOLAS CHURCH There was probably a small church in Monnickendam as early as the 13th century. This church however soon became too small for the rapidly growing population of Monnickendam and at the end of the 14th century work began on the construction of the Grote Kerk. Construction of the Grote Kerk The people chose a location on the edge of the town for the construction of the new –and at the time Catholic – Saint Nicholas church. The site offered plenty of room and was safely out of the way of the fires that often occurred in the city. Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of skippers and sailors. The construction of the Grote Kerk took at least 250 years; more or less spread over six phases. Approximately every 50 years another part of the church was completed, ending up with the south- west corner 1644. The completed building was 70 metres long, 33 metres wide and 20 metres high. The Grote Kerk is what is known as a triple-aisled church. A remarkable feature of the church is the consistent Gothic building style. One exception to the Gothic building style was the Renaissance verger’s house, built in 1626. Church tower De construction of the tower was completed in three phases. The bottom part was completed in 1520. As the reformation (1572) interrupted the process and the church became Protestant as a result of which the top of the tower (and the spire) were built in a more sober style. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Iconography analysis of the representations of the Last Judgement in late medieval France S.F Ho Master of Philosophy in History of Art 2011 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to analyse the iconographic elements in large-scale representations of the Last Judgement in late medieval France, c. 1380 – c. 1520. The study begins by examining the sudden surge of the subject in question that occurred in the second half of the fifteenth century and its iconographic evolution across geographical regions in France. Numerous depictions of the Last Judgement and iconographic differences have prompted speculation concerning its role in society. -

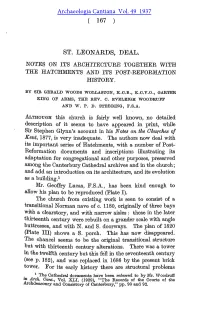

St Leonards, Deal. Notes on Its Architecture Together with the Hatchments and Its Post-Reformation History

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 49 1937 ( 167 ) ST. LEONARDS, DEAL. NOTES ON ITS ARCHITECTURE TOGETHER WITH THE HATCHMENTS AND ITS POST-REFORMATION HISTORY. BY SIR GERAUD WOODS WOLLASTON, K.C.B., K.C.V.O., GARTER KING OF ARMS, THE REV. 0. EVELEIGH WOODROTS1 AND W. P. D. STEBBESTG, F.S.A. ALTHOUGH this church is fairly well known, no detailed description of it seems to have appeared in print, while Sir Stephen Glynn's account in his Notes on the Churches of Kent, 1877, is very inadequate. The authors now deal with its important series of Hatchments, with a number of Post- Reformation documents and inscriptions illustrating its adaptation for congregational and other purposes, preserved among the Canterbury Cathedral archives and in the church; and add an introduction on its architecture, and its evolution as a building.1 Mr. Geoffry Lucas, P.S.A., has been kind enough to allow his plan to be reproduced (Plate I). The church from existing work is seen to consist of a transitional Norman nave of c. 1180, originally of three bays with a clearstory, and with narrow aisles : these in the later thirteenth century were rebuilt on a grander scale with angle buttresses, and with N. and S. doorways. The plan of 1820 (Plate III) shows a S. porch. This has now disappeared. The chancel seems to be the original transitional structure but with thirteenth century alterations. There was a tower in the twelfth century but this fell in the seventeenth century (see p. 182), and was replaced in 1686 by the present brick tower. -

Nobles and Nuremberg's Churches

Durham E-Theses Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany: A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s POPE, BENJAMIN, JOHN How to cite: POPE, BENJAMIN, JOHN (2016) Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany: A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11492/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s Benjamin John Pope Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History, Durham University 2015 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 7 The Medieval Debate. 9 ‘Not exactly established’: Historians, Towns and Nobility. .18 Liberals and Romantics . .20 The ‘Crisis’ of the Nobility . 25 Erasing the Divide . -

Download Download

virtus 25 virtus Adellijke echo’s? De invloed van de adel op de ontwikkeling van buitenplaatsen 9 langs de rivieren van het Amstelland en de Oude Rijn Gerrit van Oosterom Het Staatse ambassadegebouw in de zeventiende eeuw. Het logement van 29 Hendrick van Reede van Renswoude in Madrid, 1656-1669 virtus Maurits Ebben Naar het Oosten. Geografische verschillen in het ledenbestand van de 57 2018 Ridderlijke Duitsche Orde, Balije van Utrecht, 1640-1840 25 Renger E. de Bruin De Belgische orangistische adel I. De zuidelijke adel in het Verenigd Koninkrijk 79 der Nederlanden (1815-1830) 25 2018 Els Witte | The Bentinck family archives. Highlights and suggestions for further research 103 Menoucha Ruitenberg Bildung und Erziehung. Zur Bedeutung zweier Schlüsselkategorien für 114 Charlotte Sophie Gräfin Bentinck Christina Randig Charlotte Sophie, Joseph Eckhel and numismatics 127 Daniela Williams Craignez honte. The Bentinck coats of arms and their use as an expression 144 of the cross-border character of the family Olivier Mertens Fathers and Sons. A sketch of the noble life forms of the Bentincks in the 162 period of the Great Wars in Europe (1672-1748) Yme Kuiper Van wapenbord tot koningsboek. Herinnering, herstel en herbestemming in 179 de heraldiek van het Gulden Vlies (1559-1795) Steven Thiry 9 789087 047870 omslag Virtus 2018.indd 2 14-02-19 13:54 virtus 25 | 2018 | pp. 144-161 Olivier Mertens Craignez honte The Bentinck coats of arms and their use as an expression of the cross-border character of the family 144 The Bentinck family can be considered the paragon of a crossborder aristocratic fam ily, with branches belonging to the nobility of the Holy Roman Empire (until 1806), the Dutch nobility, the English peerage and the nobility (since 1845 high nobility or Hohe Adel) of Germany, until its abolition in 1919. -

Guide to Bowdon Parish Church and Theguide Surrounding to Area Bowdon Parish Church and the Surrounding Area

Guide to Bowdon Parish Church and theGuide Surrounding to Area Bowdon Parish Church and the Surrounding Area FREE Welcome to St Mary the Virgin, the Parish Church at Bowdon 1 AN ANCIENT CHURCH and PARISH The long ridge of Bowdon Hill is crossed by the Roman road of Watling Street (now the A56), linking Cheshire and Lancashire. There has been a landmark church on this raised site, in the centre of Bowdon, since Saxon times. A small community was established here, possibly by Archbishop Theodore, in the 7th century. Theodore set up the dioceses in the region and divided them into parishes, so Bowdon may have been one of the first. St Chad, Bishop of Mercia, in which Bowdon parish was situated in 669AD, is known to have worked nearby. The 1086 Domesday Book tells us that a mill, church and parish priest were at Bogedone (bow-shaped hill) at the time, which was held by the Norman officer, the first Hamon de Massey. There is evidence for the rebuilding of the church in stone around 1100 in Norman style and around 1320 during the reign of Edward II, with the addition of a tower, new nave with octagonal pillars and pointed arches and a south side aisle (with the old church becoming in part the north aisle). In 1510 at the time of Henry VIII, it was partially rebuilt, but not completed. 2 In 1541, at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the parish was transferred to the Diocese of Chester from the Priory of Birkenhead, which had been founded by local lord Hamon de Massey, 3rd Baron of Dunham. -

THE SOCIETY of HERALDIC ARTS Anthony Wood, PSHA David Krause, FCA, FSHA President Hon

THE SOCIETY OF HERALDIC ARTS Anthony Wood, PSHA David Krause, FCA, FSHA President Hon. Treasurer Quillion House, Over Stra on, South Petherton, Somerset 6 Corrance Road, Wyke, Bradford, TA13 5LQ UK Yorkshire BD12 9LH UK +44 (0)1460 241 115 +44 (0)1274 679 272, [email protected] John J Tunesi of Liongam, MSc, FSA Scot David R Wooten, FSHA Chairman and Hon. Secretary Webmaster 53 Hitchin Street, Baldock, Hertfordshire, SG7 6AQ UK 1818 North Taylor Street, Ste B, +44 (0)1462 892062 or +44 (0)7989 976394, Li le Rock, Arkansas 72207 USA [email protected] 001 501 200 0007, [email protected] Jane Tunesi of Liongam, MST (Cantab) William Beaver Hon. Membership Secretary Pro Tem Hon. Editor The Heraldic Craftsman 53 Hitchin Street, Baldock, Hertfordshire, SG7 6AQ UK 50 Church Way, Iffl ey, Oxford OX4 4EF UK +44 (0)1462 892062 or +44 (0)7989 976396, +44 (0)1865 778061 mailto:[email protected] [email protected] Table of Contents Badge of the Clerk to the Worshipful Company of Educators front cover Contents, Membership, Addresses and Chairman’s Message inside front cover Pugin’s Heraldic Revival, Dr JA Hilton, Assoc SHA 1 Society Ma ers 5 Le ers patent pro-forma 6 Obituary of Romilly Squires, SHA, Gordon Casely, Assoc SHA 7 Pugin’s Cross, Dr JA Hilton, Assoc SHA 9 Pugin, Cobwebs and Cadets, Hon Editor 10 Pugin at the Palace of Westminster, Baz Manning, FSHA 11 What are you doing today? G Casely and P& G Greenhill, SHA 14 That felicitous combination (Grant Macdonald), Charlo e Grosvenor, Assoc SHA 15 Enamel, Heraldry and Rugby League, Dr Peter Harrison, SHA 19 The arms of a most saintly and unfortunate lady, David Hopkinson, FSHA inside back cover Lady Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, David Hopkinson, FSHA back cover Chairman’s Message I will be standing at the registration desk at RAF Club in London on 15 February looking forward to welcoming you to the lecture, luncheon and presentation of our Le ers Patent.