English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church

Andrews University Seminary Student Journal Volume 1 Number 2 Fall 2015 Article 3 8-2015 Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church John Reeve Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reeve, John (2015) "Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church," Andrews University Seminary Student Journal: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj/vol1/iss2/3 This Invited Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andrews University Seminary Student Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seminary Student Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1-15. Copyright © 2015 John W. Reeve. FUTURE VIEWS OF THE PAST: MODELS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EARLY CHURCH JOHN W. REEVE Assistant Professor of Church History [email protected] Abstract Models of historiography often drive the theological understanding of persons and periods in Christian history. This article evaluates eight different models of the early church period and then suggests a model that is appropriate for use in a Seventh-day Adventist Seminary. The first three models evaluated are general views of the early church by Irenaeus of Lyon, Walter Bauer and Martin Luther. Models four through eight are views found within Seventh-day Adventism, though some of them are not unique to Adventism. -

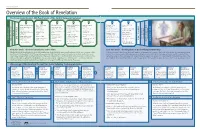

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts: Exchanges Between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Intersections Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture General Editor Karl A.E. Enenkel (Chair of Medieval and Neo-Latin Literature Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster e-mail: kenen_01@uni_muenster.de) Editorial Board W. van Anrooij (University of Leiden) W. de Boer (Miami University) Chr. Göttler (University of Bern) J.L. de Jong (University of Groningen) W.S. Melion (Emory University) R. Seidel (Goethe University Frankfurt am Main) P.J. Smith (University of Leiden) J. Thompson (Queen’s University Belfast) A. Traninger (Freie Universität Berlin) C. Zittel (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice / University of Stuttgart) C. Zwierlein (Freie Universität Berlin) volume 74 – 2021 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/inte Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Exchanges between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767 Edited by Ana Sáez-Hidalgo Berta Cano-Echevarría LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. This volume has been benefited from financial support of the research project “Exilio, diplomacia y transmisión textual: Redes de intercambio entre la Península Ibérica y las Islas Británicas en la Edad Moderna,” from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, the Spanish Research Agency (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad). -

The Great Apostasy

Theology Corner Vol. 38 – April 8th, 2018 Theological Reflections by Paul Chutikorn - Director of Faith Formation “How Do I Defend the Faith Against Mormons? (Part 1)” Have you ever been approached by Mormon missionaries coming to your door and talking about why it is that the Catholic Church is not the true faith? I know I have. Knowing your faith is important in these situations so you can dispel any misunderstandings about Catholicism. As always, you have to approach them with charity, otherwise debating with them would be pointless. In addition to knowing your faith pretty well, it is also beneficial to know a few things about that they believe so that you understand what it is that we absolutely cannot accept due to logic, scripture, and Church teaching throughout the ages. There are a few major errors to address about Mormonism, and the one that I will address today is what they would refer to as “The Great Apostasy.” As a way for them to convince us that the Catholic Church is no longer authoritative is by mentioning the theory that it became entirely corrupted after the death of the last apostle. They believe that the apostles were the only ones who truly preached the truth that Jesus handed down to them, and after the last one died (John around 100AD) the faith became “apostate” or abandoned. According to Mormonism, this apostasy lasted until the 1800’s when Joseph Smith restored the faith. The first issue with this theory is that there is no historical evidence whatsoever for there ever being a complete universal apostasy. -

A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 4-16-2021 The Not-So-Great Apostasy?: A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy Rylie Slone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons SENIOR THESIS APPROVAL This Honors thesis entitled The Not-So-Great Apostasy? A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy written by Rylie Slone and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion of the Carl Goodson Honors Program meets the criteria for acceptance and has been approved by the undersigned readers. __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, thesis director __________________________________ Dr. Doug Reed, second reader __________________________________ Dr. Jay Curlin, third reader __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, Honors Program director Introduction When one takes time to look upon the foundational arguments that form Mormonism, one of the most notable presuppositions is the argument of the Great Apostasy. Now, nearly all new religious movements have some kind of belief that truth at one point left the earth, yet they were the only ones to find it. The idea of esoteric and special revealed knowledge is highly regarded in these religious movements. But what exactly makes the Mormon Great Apostasy so distinct? Well, James Talmage, a revered Mormon scholar, said that the Great Apostasy was the perversion of biblical truth following the death of the apostles. Because of many external and internal conflicts, he believes that the church marred the legitimacies of Scripture so much that truth itself had been lost from the earth.1 This truth, he asserts, was not found again until Joseph Smith received his divine revelations that led to the Book of Mormon in the nineteenth century. -

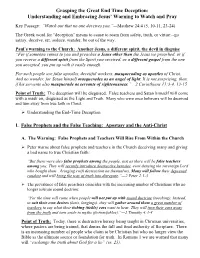

Grasping the Great End Time Deception: Understanding and Embracing Jesus' Warning to Watch and Pray

Grasping the Great End Time Deception: Understanding and Embracing Jesus’ Warning to Watch and Pray Key Passage: “Watch out that no one deceives you.”—Matthew 24:4 (5, 10-11, 23-24) The Greek word for “deception” means to cause to roam from safety, truth, or virtue:--go astray, deceive, err, seduce, wander, be out of the way. Paul’s warning to the Church: Another Jesus, a different spirit, the devil in disguise “For if someone comes to you and preaches a Jesus other than the Jesus we preached, or if you receive a different spirit from the Spirit you received, or a different gospel from the one you accepted, you put up with it easily enough. For such people are false apostles, deceitful workers, masquerading as apostles of Christ. And no wonder, for Satan himself masquerades as an angel of light. It is not surprising, then, if his servants also masquerade as servants of righteousness.”—2 Corinthians 11:3-4, 13-15 Point of Truth: The deception will be disguised. False teachers and Satan himself will come with a mask on, disguised as the Light and Truth. Many who were once believers will be deceived and turn away from true faith in Christ. Ø Understanding the End-Time Deception I. False Prophets and the False Teaching: Apostasy and the Anti-Christ A. The Warning: False Prophets and Teachers Will Rise From Within the Church Ø Peter warns about false prophets and teachers in the Church deceiving many and giving a bad name to true Christian faith: “But there were also false prophets among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you. -

Recusant Literature Benjamin Charles Watson University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Librarians Research Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2003 Recusant Literature Benjamin Charles Watson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, History Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Benjamin Charles, "Recusant Literature" (2003). Gleeson Library Librarians Research. Paper 2. http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/2 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Librarians Research by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECUSANT LITERATURE Description of USF collections by and about Catholics in England during the period of the Penal Laws, beginning with the the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558 and continuing until the Catholic Relief Act of 1791, with special emphasis on the Jesuit presence throughout these two centuries of religious and political conflict. Introduction The unpopular English Catholic Queen, Mary Tudor died in 1558 after a brief reign during which she earned the epithet ‘Bloody Mary’ for her persecution of Protestants. Mary’s Protestant younger sister succeeded her as Queen Elizabeth I. In 1559, during the first year of Elizabeth’s reign, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity, declaring the state-run Church of England as the only legitimate religious authority, and compulsory for all citizens. -

Sacred Text—Sacred Space Studies in Religion and the Arts

Sacred Text—Sacred Space Studies in Religion and the Arts Editorial Board James Najarian Boston College Eric Ziolkowski Lafayette College VOLUME 4 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/sart Sacred Text—Sacred Space Architectural, Spiritual and Literary Convergences in England and Wales Edited by Joseph Sterrett and Peter Thomas LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Sacred text, sacred space : architectural, spiritual, and literary convergences in England and Wales / edited by Joseph Sterrett and Peter Thomas. p. cm. — (Studies in religion, ISSN 1877-3192 ; v. 4) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20299-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Christianity and the arts—England— History. 2. Christianity and the arts—Wales—History. I. Sterrett, Joseph. II. Thomas, Peter Wynn. BR744.S23 2011 261.5’70942—dc23 2011034521 ISSN 1877–3192 ISBN 978 90 04 20299 3 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............................................................................. vii List of Illustrations ............................................................................ -

Catholic Primaries in the Ralph Sherwin Catholic

Admissions Policy for Catholic Primary Schools in The St Ralph Sherwin Catholic Multi-Academy Trust School Published Parish(es) served Located within Admission Local Authority Number St Francis of Assisi, Long English Martyrs Catholic Voluntary Eaton Academy 40 The Assumption, Beeston Derbyshire Bracken Road, Long Eaton, Derbyshire, St John the Evangelist, NG10 4DA Stapleford St Edward's Catholic Primary Academy 30 Saints Peter & Paul, Derbyshire Newhall Road, Swadlincote, Derbyshire DE11 Swadlincote 0BD St Joseph's Catholic Academy 30 Our Lady & St Joseph, Derbyshire Chesterfield Road, Matlock, Derbyshire DE4 Matlock with Our Lady and St 3ET Teresa of Lisieux, Wirksworth All Saints, Hassop with English Martyrs, Bakewell All Saints’ Catholic Primary School 14 All Saints, Glossop Derbyshire Church Street, Old Glossop, Derbyshire St Mary Crowned, Glossop SK13 7RJ [email protected] Christ the King Catholic Primary 30 Christ the King, Alfreton with Derbyshire School St Patrick and St Bridget, Clay Firs Avenue, Alfreton, Derbyshire DE55 7EN Cross St Anne's Catholic Primary School 45 St Anne, Buxton Derbyshire Lightwood Road, Buxton, Derbyshire SK17 St John Fisher and St Thomas 7AN More, Chapel-en-le-Frith with Immaculate Heart of Mary, Tideswell Sacred Heart, Whaley Bridge St Charles’ Catholic Primary School 30 St Charles Borromeo, Derbyshire The Carriage Drive, Hadfield, Derbyshire Hadfield SK13 1PJ Immaculate Conception, Charlesworth with St Margaret Gamesley St Elizabeth's Catholic Primary School 30 Our Lady of Perpetual -

The Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist 20 June 2021 - Ordinary Time XII Most Rev

The Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist 20 June 2021 - Ordinary Time XII Most Rev. Edward C. Malesic Bishop of Cleveland SATURDAY, 19 JUNE 2021 THURSDAY, 24 JUNE 2021 Saint Romuald Nativity of John the Baptist Cathedral open 6:30 am - 5:30 pm Is 49:1-6; Acts 13:22-26; Lk 1:57-66, 80 1007 Superior Avenue E 2 Cor 12:1-10; Mt 6:24-34 Cathedral open 6:00 am – 6:00 pm Cleveland OH 44114-2582 216-771-6666 Vello Veriam 7:15 Sandra Cancasci 4:30 People of the Cathedral Parish 12:00 Reno & Beverely Alessio [email protected] 2:00 pm Wedding: Chonko / Shepard Bill Sweeney web: SaintJohnCathedral.com SUNDAY, 20 JUNE 2021 FRIDAY, 25 JUNE 2021 Since 1848, this historic Cathedral Jb 38:1, 8-11; 2 Cor 5:14-17; Mk 4:35-41 Gn 17:1, 9-10, 15-22; Mt 8:1-4 Church in the middle of Cleveland’s Cathedral open 7:30 am – 6:30 pm Cathedral open 6:00 am – 6:00 pm civic center has served Catholics and PIC Collection 7:15 Christine Serra the wider community of Cleveland 12:00 Christ Child Society: Russell as a prayerful oasis and spiritual MONDAY, 21 JUNE 2021 Krinsky, Carol Mariano, Patricia home. As the Bishop’s Church, the St. Aloysius Gonzaga Neff, John Moenk Cathedral is the “Mother Church” for Gn 12:1-9; Mt 7:1-5 over 710,000 Catholics in the Diocese James Kasper Cathedral open 6:00 am – 6:00 pm of Cleveland. -

Homily for the Feast of the English College Martyrs, 2Nd December

nd Homily for the Feast of the English College Martyrs, 2 December 2019, at Our Lady of Grace Catholic Church, Prestwich, Manchester Readings: 2 Maccabees 7:1-2.9-14; 1 John 5:1-5; Gospel: Matthew 10:28-33 England is our mission territory. My house job one year was to be the College archivist and one day I came across a letter, dated 1580, that St Charles Borromeo had written in Italian to the then Rector of the English College. He said that he had greatly enjoyed the recent visit to him of seminarians on their way to the English Mission. He added that he would be glad to provide hospitality to other English priests in the future. I realised that he must have been referring to St Ralph Sherwin. I imagine that these days an inexpert student such as I was would not have immediate access to such a precious document but I must say it was marvellous actually to hold a letter from a saint about a saint with whom through our shared association with the College I am connected. I read up about that stay subsequently. Apparently St Ralph and St Edmund Campion stayed with St Charles Borromeo for eight days and each evening after dinner they conversed. What they discussed precisely I do not think anybody knows. Certainly, St Charles had a particular affinity for England: he wore about his neck a small picture of St John Fisher a fellow bishop who, of course, had been martyred in 1535. The situation in England had deteriorated in the 1570s, especially following Pope Pius V’s 1570 Bull excommunicating Elizabeth I and exonerating Catholics of obedience to her. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Iconography analysis of the representations of the Last Judgement in late medieval France S.F Ho Master of Philosophy in History of Art 2011 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to analyse the iconographic elements in large-scale representations of the Last Judgement in late medieval France, c. 1380 – c. 1520. The study begins by examining the sudden surge of the subject in question that occurred in the second half of the fifteenth century and its iconographic evolution across geographical regions in France. Numerous depictions of the Last Judgement and iconographic differences have prompted speculation concerning its role in society.