An Evaluation of Rapture Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church

Andrews University Seminary Student Journal Volume 1 Number 2 Fall 2015 Article 3 8-2015 Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church John Reeve Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reeve, John (2015) "Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church," Andrews University Seminary Student Journal: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj/vol1/iss2/3 This Invited Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andrews University Seminary Student Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seminary Student Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1-15. Copyright © 2015 John W. Reeve. FUTURE VIEWS OF THE PAST: MODELS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EARLY CHURCH JOHN W. REEVE Assistant Professor of Church History [email protected] Abstract Models of historiography often drive the theological understanding of persons and periods in Christian history. This article evaluates eight different models of the early church period and then suggests a model that is appropriate for use in a Seventh-day Adventist Seminary. The first three models evaluated are general views of the early church by Irenaeus of Lyon, Walter Bauer and Martin Luther. Models four through eight are views found within Seventh-day Adventism, though some of them are not unique to Adventism. -

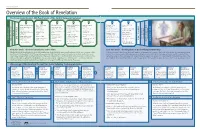

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Holy Trinity Lutheran Church Des Moines, WA April 17, 2016

Holy Trinity Lutheran Church feels, an enemy that the late David Bowie Des Moines, WA sang about: The enemy is pressure and we all know how the effects that pressure puts on us. April 17, 2016 It can tire and wear us out. It can cause unbelievable stress and worry. It can overwhelm to exhaustion or depression. John 10:22-30 And where do we feel the effects of this enemy? Perhaps the shorter-answered ques- (In) Vulnerable Sheep tion is where don’t we? Every one of us feels pressure in our vocations – those roles that we Hymns: 374 – 375 – 360 – 312 are given in life: at work, at home, in the Closing: 436 church. Every “job” that we have comes with All Scripture quotations from NIV 1984 pressures of expectation; pressures of suc- cess; pressures of responsibility. And those 22 Then came the Feast of Dedication at pressures can come from the outside – people Jerusalem. It was winter, 23 and Jesus was in placing them onto us, both fairly and unfairly. the temple area walking in Solomon’s Or they can come from within – pressures Colonnade. 24 The Jews gathered around that we reasonably, and unreasonably, place him, saying, “How long will you keep us in upon ourselves. suspense? If you are the Christ, tell us But more dangerous than the vocational plainly.” pressures that we face are the spiritual 25 Jesus answered, “I did tell you, but you pressures that narrow in on us every single do not believe. The miracles I do in my day. And again, these pressures come from Father’s name speak for me, 26 but you do not both the outside, and also from the inside. -

The Service of Witness to the Resurrection

THE SERVICE OF WITNESS TO THE RESURRECTION Information, guidelines, and policies to assist in planning a memorial service. The name of the service on the occasion of death is ‘The Service of Witness to the Resurrection,’ which reflects our fundamental beliefs that, in Christ, death has been conquered and the promise of eternal life is affirmed. 1200 Marquette Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55403 612.332.3421 — westminstermpls.org PURPOSE OF THIS BOOKLET The purpose of this booklet is to assist members and friends in making arrangements and planning a service of remembrance at the time of the death of a loved one. Our Christian theology shapes not only our beliefs about death, but also how we celebrate the life of the one who has died. We trust that you will accept this booklet in the spirit it is offered—with joyful gratitude born of the conviction that, “neither death nor life…nor anything else in all creation, has the power to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Romans 8) The Congregational Care Council of Westminster Presbyterian Church SERVICES ON THE OCCASION OF DEATH The name of the service on the occasion of death is ‘The Service of Witness to the Resurrection,’ reflecting our fundamental beliefs that, in Christ, death has been conquered, and the promise of eternal life is affirmed. The presence or absence of a casket or urn does not change the name or purpose of the service. The uniqueness of the Christian faith is especially apparent when death comes. Our hope of eternal life is based not upon a person’s worth, but upon the graciousness of God. -

Visions of the End? Revelation and Climate Change

Visions of the End? Revelation and Climate Change By The Revd Professor T.J. Gorringe; a chapter from Sebastian Kim and Jonathan Draper (eds.) Christianity and the Renewal of Nature, SPCK, 2011; reproduced with kind permission of the author and publisher. Rev 8: 1 When the Lamb opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven for about half an hour. In chapter four of Revelation the author tells us that the song of praise before God ‘never ceases’ (4:8), but now there is silence. ‘Heaven seems to hold its breath because of what is about to happen on earth’. Perhaps the author is thinking of the passage in 2 Esdras where the world returns to its “original silence” as “at the beginning of creation” when nobody will be left alive (7:30 cf.6:39)i. It is an intensely dramatic image which has caught people’s imaginations all the way from the first century to Ingmar Bergman. It could speak about the fear we feel about the possible effects of climate change as represented by James Lovelock in The Revenge of Gaia, or Mark Lynas in Six Degrees. But the silence does not last. Seven trumpets are given to seven angels. These may be the seven archangels found in Jewish tradition and in this tradition trumpets are used to warn or to call. “All you inhabitants of the world, when a trumpet is blown, hear!” says Isaiah(Is.18:3) It is the task of prophets as watchmen to call the people to “give heed to the sound of the trumpet”, to hear the warning says Jeremiah (Jer 6:17 ). -

Introduction to the Millennial Kingdom

What Must Take Place After This (The Millennial Kingdom & the Great White Throne) Text: Revelation 20 Main Idea: When Christ returns He will defeat His enemies, have Satan bound, and set up His throne in Jerusalem and reign for a thousand years on the earth. At the end of the millennial reign Christ will defeat Satan, who will be released, and an army of unbelievers. At that point the whole earth will be destroyed, and all the unsaved through the ages will be resurrected and given bodies to stand before the Great White Throne Judgment and will be cast into eternal hell to be tormented forever and ever. Introduction to the Millennial Kingdom The Three Major Positions: • Amillennialism: The “a” means without. This is misleading because those who hold this position do not reject the concept of an earthly millennium, a kingdom. They believe Old Testament prophecies of the Messiah’s kingdom, but believe that those prophesies are being fulfilled ______currently__________, either by the saints reigning in heaven with Christ, or by the church on the earth. Amillennialists believe that the millennial kingdom is happening right now spiritually. But they do deny a literal reign of Christ on the earth. The hermeneutic of the Amillennialist forces them to interpret everything spiritual. • Postmillennialism: “Postmillennialism is in some ways the opposite of premillennialism. Premillennialism teaches that Christ will return before the Millennium; postmillennialism teaches that He will return at the end of the Millennium. Premillennialism teaches that the period immediately before Christ’s return will be the worst in human history; postmillennialism teaches that before His return will come the best period in history, so that Christ will return at the end of a long golden age of peace and harmony….That golden age, according to postmillennialism, will result from the spread of the ______Gospel___________ throughout the world and the conversion of a majority of the human race to Christianity. -

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603. Coral Georgina Stoakes, Sidney Sussex College, December, 2016. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. At 79,339 words it does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the History Degree Committee. Abstract Early modern English Catholic eschatology, the belief that the present was the last age and an associated concern with mankind’s destiny, has been overlooked in the historiography. Historians have established that early modern Protestants had an eschatological understanding of the present. This thesis seeks to balance the picture and the sources indicate that there was an early modern English Catholic counter narrative. This thesis suggests that the Catholic eschatological understanding of contemporary events affected political action. It investigates early modern English Catholic eschatology in the context of proscription and persecution of Catholicism between 1558 and 1603. -

The Great Tribulation 2

SMALL GROUP DISCUSSION GUIDE Sermon Study Guide Pastor Phil Newby 1. Read Revelation 12:1-6. How has Satan’s evil desire to ruin God’s plans March 1, 2020 resulted in persecution of Israel throughout history? SATAN’S HEYDAY – THE GREAT TRIBULATION 2. How would you explain the gap between verse 5 and verse 6? REVELATION 12-13 CHAPTER 12 – SATAN’S ROLE – PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE 3. Read Revelation 12:7-18. Why is the second half of the Tribulation the worst and how do people overcome Satan’s fury during this time? (See verse 11) 1. A GREAT SIGN – VERSES 1-2 4. Read Revelation 13:1-10. Why is this beast often referred to as the A. The woman here represents _____________________ . Antichrist? Joseph’s dream in Genesis 37:9-11 uses a similar description for his parents, Jacob and Rachel, and his eleven brothers. 5. What world conquerors from the past have foreshadowed the end times Antichrist? (If you really want to dig go to Daniel 7!) B. Her labor pain describes Israel’s pain waiting for the ________________ to come and deliver them from Gentile oppression. 6. What does it mean to have endurance and faithfulness as a believer in Christ? 2. ANOTHER SIGN – VERSES 3-6 A. The dragon represents __________________. 7. Read Revelation 13:11-18. How is the landscape of churches today setting The seven heads with crowns and ten horns represent Satan’s use of the stage for the apostate church of the end times? earthly kingdoms to oppress Israel. (See Daniel 7:23-25, Revelation 17:9-10) 8. -

The Christology of Mark

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1972 The Christology of Mark Gregory L. Jackson Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Gregory L., "The Christology of Mark" (1972). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1511. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1511 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHRISTOLOGY OF MARK by Gregory L. Jackson A Thesis submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree MASTER OF DIVINITY from Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Waterloo, Ontario May 30, 1972 n^^ty of *he Library "-'uo University College UMI Number: EC56448 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI EC56448 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml -

The Rapture in Twenty Centuries of Biblical Interpretation

TMSJ 13/2 (Fall 2002) 149-171 THE RAPTURE IN TWENTY CENTURIES OF BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION James F. Stitzinger Associate Professor of Historical Theology The coming of God’s Messiah deserves closer attention than it has often received. The future coming of the Messiah, called the “rapture,” is imminent, literal and visible, for all church saints, before the hour of testing, premillennial, and, based on a literal hermeneutic, distinguishes between Israel and the church. The early church fathers’ views advocated a sort of imminent intra- or post- tribulationism in connection with their premillennial teaching. With a few exceptions, the Medieval church writers said little about a future millennium and a future rapture. Reformation leaders had little to say about prophetic portions of Scripture, but did comment on the imminency of Christ’s return. The modern period of church history saw a return to the early church’s premillennial teaching and a pretribulational rapture in the writings of Gill and Edwards, and more particularly in the works of J. N. Darby. After Darby, pretribulationism spread rapidly in both Great Britain and the United States. A resurgence of posttribulationism came after 1952, accompanied by strong opposition to pretribulationism, but a renewed support of pretribulationism has arisen in the recent past. Five premillennial views of the rapture include two major views—pretribulationism and posttribulation-ism—and three minor views—partial, midtribulational, and pre-wrath rapturism. * * * * * Introduction The central theme of the Bible is the coming of God’s Messiah. Genesis 3:15 reveals the first promise of Christ’s coming when it records, “He shall bruise you on the head, And you shall bruise him on the heel.”1 Revelation 22:20 unveils the last promise when it records “He who testifies to these things says, ‘Yes, I am coming quickly,’ Amen. -

A Critical Analysis Ofthe Millennial Reign of Christ in Revelation 20: 1-10

A critical analysis ofthe Millennial reign ofChrist in Revelation 20: 1-10. BY REV. HUMPHREY MWANGI WAWERU Submitted in fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree ofMaster of Theology (New Testament biblical studies) In the faculty ofHumanities School ofTheology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg. January 2001 Supervisor: Prof. Jonathan A. Draper. ABSTRACT This thesis addresses the issue ofthe millennial reign of Christ in Revelation 20: 1-1 O. It is an attempt to investigate whether the millennium is a future event or already inaugurated. The Apocalypse has been the focus ofattention ofmany end time movements down through the ages. This thesis picks up one ofthe most popular issues out ofsuch a focus. One ofthe issues in the Apocalypse of John is the expectation ofa thousand year reign of Christ. During the period of early Christianity up to the middle ages the question ofthe nature ofthe millennium has been controversial. Recently the debate over the millennial reign of Christ in the Apocalypse has intensified more than ever before. Three major views have been advocated and such views have brought in a greater dilemma, since the reader ofthe Apocalypse has to choose one ofthe views. Having grown up in an evangelical religious background, which places emphasis upon apocalyptic ideologies; I found myselfbecoming more and more attracted to this debate. At last I have entered the wagon with a view to demonstrate, in my own way, that the millennial reign is already actualised rather than expected. This sounds very controversial compared to what has always been thought by many Christians since their early days ofSunday School. -

The Great Apostasy

Theology Corner Vol. 38 – April 8th, 2018 Theological Reflections by Paul Chutikorn - Director of Faith Formation “How Do I Defend the Faith Against Mormons? (Part 1)” Have you ever been approached by Mormon missionaries coming to your door and talking about why it is that the Catholic Church is not the true faith? I know I have. Knowing your faith is important in these situations so you can dispel any misunderstandings about Catholicism. As always, you have to approach them with charity, otherwise debating with them would be pointless. In addition to knowing your faith pretty well, it is also beneficial to know a few things about that they believe so that you understand what it is that we absolutely cannot accept due to logic, scripture, and Church teaching throughout the ages. There are a few major errors to address about Mormonism, and the one that I will address today is what they would refer to as “The Great Apostasy.” As a way for them to convince us that the Catholic Church is no longer authoritative is by mentioning the theory that it became entirely corrupted after the death of the last apostle. They believe that the apostles were the only ones who truly preached the truth that Jesus handed down to them, and after the last one died (John around 100AD) the faith became “apostate” or abandoned. According to Mormonism, this apostasy lasted until the 1800’s when Joseph Smith restored the faith. The first issue with this theory is that there is no historical evidence whatsoever for there ever being a complete universal apostasy.