Read Only Vol 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reader's Companion to John Cowper Powys's a Glastonbury Romance

John Cowper Powys’s A Glastonbury Romance: A Reader’s Companion Updated and Expanded Edition W. J. Keith December 2010 . “Reader’s Companions” by Prof. W.J. Keith to other Powys works are available at: https://www.powys-society.org/Articles.html Preface The aim of this list is to provide background information that will enrich a reading of Powys’s novel/ romance. It glosses biblical, literary and other allusions, identifies quotations, explains geographical and historical references, and offers any commentary that may throw light on the more complex aspects of the text. Biblical citations are from the Authorized (King James) Version. (When any quotation is involved, the passage is listed under the first word even if it is “a” or “the”.) References are to the first edition of A Glastonbury Romance, but I follow G. Wilson Knight’s admirable example in including the equivalent page-numbers of the 1955 Macdonald edition (which are also those of the 1975 Picador edition), here in square brackets. Cuts were made in the latter edition, mainly in the “Wookey Hole” chapter as a result of the libel action of 1934. References to JCP’s works published in his lifetime are not listed in “Works Cited” but are also to first editions (see the Powys Society’s Checklist) or to reprints reproducing the original pagination, with the following exceptions: Wolf Solent (London: Macdonald, 1961), Weymouth Sands (London: Macdonald, 1963), Maiden Castle (ed. Ian Hughes. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1990), Psychoanalysis and Morality (London: Village Press, 1975), The Owl, the Duck and – Miss Rowe! Miss Rowe! (London: Village Press, 1975), and A Philosophy of Solitude, in which the first English edition is used. -

The Seaxe Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society

The Seaxe Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society Editor – Stephen Kibbey, 3 Cleveland Court, Kent Avenue, Ealing, London, W13 8BJ (Telephone: 020 8998 5580 – e-mail: [email protected]) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… No.56 Founded 1976 September 2009 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Queen Charlotte’s Hatchment returns to Kew. Photo: S. Kibbey Peach Froggatt and the restored Queen Charlotte‟s Hatchment in Kew Palace. Late afternoon on Thursday 23rd July 2009 a small drinks party was held at Kew Palace in honour of Peach Froggatt, one of our longest serving members. As described below in Peach‟s own words, the hatchment for Queen Charlotte, King George III‟s wife, was rescued from a skip after being thrown out by the vicar of St Anne‟s Church on Kew Green during renovation works. Today it is back in the house where 191 years ago it was hung out on the front elevation to tell all visitors that the house was in mourning. “One pleasant summer afternoon in 1982 when we were recording the “Funeral Hatchments” for Peter Summers “Hatchments in Britain Series” we arrived at Kew Church, it was our last church for the day. The church was open and ladies of the parish were busy polishing and arranging flowers, and after introducing ourselves we settled down to our task. Later the lady in charge said she had to keep an appointment so would we lock up and put the keys through her letterbox. After much checking and photographing we made a thorough search of the church as two of the large hatchments were missing. Not having any luck we locked the church and I left my husband relaxing on a seat on Kew Green while I returned the keys. -

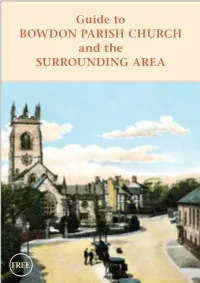

Guide to BOWDON PARISH CHURCH and the SURROUNDING AREA

Guide to BOWDON PARISH CHURCH and the SURROUNDING AREA FREE i An Ancient Church and Parish Welcome to Bowdon and the Parish The long ridge of Bowdon Hill is crossed by the Roman road of Watling Street, now forming some of the A56 which links Cheshire and Lancashire. Church of St Mary the Virgin Just off this route in the raised centre of Bowdon, a landmark church seen from many miles around has stood since Saxon times. In 669, Church reformer Archbishop Theodore divided the region of Mercia into dioceses and created parishes. It is likely that Bowdon An Ancient Church and Parish 1 was one of the first, with a small community here since at least the th The Church Guide 6 7 century. The 1086 Domesday Book tells us that at the time a mill, church and parish priest were at Bogedone (bow-shaped ‘dun’ or hill). Exterior of the Church 23 It was held by a Norman officer, the first Hamon de Massey. The church The Surrounding Area 25 was rebuilt in stone around 1100 in Norman style then again in around 1320 during the reign of Edward II, when a tower was added, along with a new nave and a south aisle. The old church became in part the north aisle. In 1510 at the time of Henry VIII it was partially rebuilt, but the work was not completed. Old Bowdon church with its squat tower and early 19th century rural setting. 1 In 1541 at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the parish was transferred to the Diocese of Chester from the Priory of Birkenhead, which had been founded by local lord Hamon de Massey, 3rd Baron of Dunham. -

List of Freemasons from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation , Search

List of Freemasons From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation , search Part of a series on Masonic youth organizations Freemasonry DeMolay • A.J.E.F. • Job's Daughters International Order of the Rainbow for Girls Core articles Views of Masonry Freemasonry • Grand Lodge • Masonic • Lodge • Anti-Masonry • Anti-Masonic Party • Masonic Lodge Officers • Grand Master • Prince Hall Anti-Freemason Exhibition • Freemasonry • Regular Masonic jurisdictions • Opposition to Freemasonry within • Christianity • Continental Freemasonry Suppression of Freemasonry • History Masonic conspiracy theories • History of Freemasonry • Liberté chérie • Papal ban of Freemasonry • Taxil hoax • Masonic manuscripts • People and places Masonic bodies Masonic Temple • James Anderson • Masonic Albert Mackey • Albert Pike • Prince Hall • Masonic bodies • York Rite • Order of Mark Master John the Evangelist • John the Baptist • Masons • Holy Royal Arch • Royal Arch Masonry • William Schaw • Elizabeth Aldworth • List of Cryptic Masonry • Knights Templar • Red Cross of Freemasons • Lodge Mother Kilwinning • Constantine • Freemasons' Hall, London • House of the Temple • Scottish Rite • Knight Kadosh • The Shrine • Royal Solomon's Temple • Detroit Masonic Temple • List of Order of Jesters • Tall Cedars of Lebanon • The Grotto • Masonic buildings Societas Rosicruciana • Grand College of Rites • Other related articles Swedish Rite • Order of St. Thomas of Acon • Royal Great Architect of the Universe • Square and Compasses Order of Scotland • Order of Knight Masons • Research • Pigpen cipher • Lodge • Corks Eye of Providence • Hiram Abiff • Masonic groups for women Sprig of Acacia • Masonic Landmarks • Women and Freemasonry • Order of the Amaranth • Pike's Morals and Dogma • Propaganda Due • Dermott's Order of the Eastern Star • Co-Freemasonry • DeMolay • Ahiman Rezon • A.J.E.F. -

Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2002 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, July 2004 Copyright © 2002 by Ian Hancock, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Michael Zimmermann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Guenter Lewy, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Mark Biondich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Denis Peschanski, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Viorel Achim, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by David M. Crowe, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................i Paul A. Shapiro and Robert M. Ehrenreich Romani Americans (“Gypsies”).......................................................................................................1 Ian -

Psypioneer V1 N19 Nov 2005

PSYPIONEER Founded by Leslie Price Edited by Paul Gaunt An Electronic Newsletter Volume 1, No 19. November 2005. Highlights of this issue Dr. Robin John Tillyard. 233 Mrs. Billing’s Mediumship. 246 Notes by the way. 249 A life-size portrait of ‘Katie King’ 252 How to obtain this Newsletter. 254 …………………………………………… DR. ROBIN JOHN TILLYARD 1881-1937- a forgotten Australian psychical researcher. Introduction Robin Tillyard was born in Norwich, England on January 31 1881, and educated at Dover College, and Queens College Cambridge. From 1904-13 he was Mathematics and Science Master at Sydney Grammar School, Australia. From1914-17 he was a fellow in Zoology at Sydney University, becoming lecturer in Zoology in 1917. He served as chief of the Biological Department, Cawthorn Institute, New Zealand from 1921-28. In 1928 Tillyard became the Chief Entomologist to the Commonwealth of Australia. Tillyard became interested in psychical research and worked closely with Harry Price on his visits to England, in 1926 becoming a Vice-President of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research (NLPR). Tillyard became convinced of survival of the human personality after death through his experiences with “Margery” (Mrs Mina Stinson Crandon 1888-1941) in a solus sitting with Margery on August 10th 1928. In its August 18 1928 edition the scientific journal Nature published his findings. Then a tragic prediction through another medium was fulfilled on January 13 1937, when Dr Tillyard was killed in a car crash. 233 Working with Harry Price. In 1926 Tillyard co-operated with Price and conducted a special test séance with a young medium found by Harry Price in 1923, who became widely known as Stella C. -

Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime

AGENDA Meeting PoliceandCrimeCommittee Date Thursday25October2012 Time 10.00am Place Chamber,CityHall,TheQueen's Walk,London,SE12AA Copiesofthereportsandanyattachmentsmaybefoundat http://www.london.gov.uk/who-runs- london/the-london-assembly/committees/police-and-crime-committee MostmeetingsoftheLondonAssemblyanditsCommitteesarewebcastliveat http://www.london.gov.uk/who-runs-london/the-london-assembly/webcasts whereyoucanalso viewpastmeetings. MembersoftheCommittee JoanneMcCartney(Chair) JamesCleverly JennyJones(DeputyChair) LenDuvall CarolinePidgeon(DeputyChair) MuradQureshi TonyArbour NavinShah JennetteArnoldOBE FionaTwycross VictoriaBorwick Vacancy AmeetingoftheCommitteehasbeencalledbytheChairoftheCommitteetodealwiththebusiness listedbelow.Thismeetingwillbeopentothepublic.Thereisaccessfordisabledpeople,and inductionloopsareavailable. MarkRoberts,ExecutiveDirectorofSecretariat Wednesday17October2012 FurtherInformation Ifyouhavequestions,wouldlikefurtherinformationaboutthemeetingorrequirespecialfacilities pleasecontact:JohnJohnsonorAnthonyJackson;Telephone:02079834926/4894;E-mail: [email protected]/[email protected];Minicom:02079834458 FormediaenquiriespleasecontactMarkDemery,Tel:02079835769,email: [email protected] Ifyouhaveanyquestionsaboutindividualreportspleasecontactthereportauthorwhosedetailsare attheendofeachreport. Thereislimitedundergroundparkingfororangeandbluebadgeholders,whichwillbeallocatedona first-comefirst-servedbasis.PleasecontactFacilitiesManagement(02079834750)inadvanceif -

The Campaign to Abolish Imprisonment for Debt In

THE CAMPAIGN TO ABOLISH IMPRISONMENT FOR DEBT IN ENGLAND 1750 - 1840 A thesis submitted in partial f'ulf'ilment of' the requirements f'or the Degree of' Master of' Arts in History in the University of' Canterbury by P.J. LINEHAM University of' Canterbury 1974 i. CONTENTS CHAPI'ER LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES • . ii PREFACE . • iii ABSTRACT . • vii ABBREVIATIONS. • •• viii I. THE CREDITOR'S LAW • • • • . • • • • 1 II. THE DEBTOR'S LOT • • . • • . 42 III. THE LAW ON TRIAL • • • • . • . • • .. 84 IV. THE JURY FALTERS • • • • • • . • • . 133 v. REACHING A VERDICT • • . • . • 176 EPILOGUE: THE CREDITOR'S LOT . 224 APPENDIX I. COMMITTALS FOR DEBT IN 1801 IN COUNTY TOTALS ••••• • • • • • 236 II. SOCIAL CLASSIFICATION OF DEBTORS RELEASED BY THE COURT, 1821-2 • • • 238 III. COMMITTALS FOR DEBT AND THE BUSINESS CLIMATE, 1798-1818 . 240 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 242 ii. LIST OF TABLES TABLE I. Social Classirication of Debtors released by the Insolvent Debtors Court ••••••••• • • • 50 II. Prisoners for Debt in 1792. • • • • • 57 III. Committals to Ninety-Nine Prisons 1798-1818 •••••••••••• • • 60 IV. Social Classification of Thatched House Society Subscribers • • • • • • 94 v. Debtors discharged annually by the Thatched House Society, 1772-1808 ••••••••••• • • • 98 VI. Insolvent Debtors who petitioned the Court • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 185 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE ~ I. Committals for Debt in 1801. • • • • • 47 II. Debtors and the Economic Climate •••••••• • • • • • • • 63 iii. PREFACE Debtors are the forgotten by-product of every commercial society, and the way in which they are treated is often an index to the importance which a society attaches to its commerce. This thesis examines the English attitude to civil debtors during an age when commerce increased enormously. -

Author Title Place of Publication Publisher Date Special Collection Wet Leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 up Cain

Books Author Title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection Wet leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Up Cain London, United Kingdom Cain of London 197? Up and coming [USA] [s.n.] 197? Welcome to the circus shirkus [Townsville, Qld, Australia] [Student Union, Townsville College of [1978] Advanced Education] A zine about safer spaces, conflict resolution & community [Sydney, NSW, Australia] Cunt Attack and Scumsystemspice 2007 Wimmins TAFE handbook [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] [s.n.] [1993] A woman's historical & feminist tour of Perth [Perth, WA, Australia] [s.n.] nd We are all lesbians : a poetry anthology New York, NY, USA Violet Press 1973 What everyone should know about AIDS South Deerfield, MA, USA Scriptographic Publications Pty Ltd 1992 Victorian State Election 29 November 2014 : HIV/AIDS : What [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] Victorian AIDS Council/Living Positive 2014 your government can do Victoria Feedback : Dixon Hardy, Jerry Davis [USA] [s.n.] c. 1980s Colin Simpson How to increase the size of your penis Sydney, NSW, Australia Venus Publications Pty.Ltd 197? HRC Bulletin, No 72 Canberra, ACT, Australia Humanities Research Centre ANU 1993 It was a riot : Sydney's First Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Sydney, NSW, Australia 78ers Festival Events Group 1998 Biker brutes New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Colin Simpson HIV tests and treatments Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia AIDS Council of NSW (ACON) 1997 Fast track New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1980 Colin Simpson Denver University Law Review Denver, CO, -

Grosvenor Prints Catalogue for July 2007

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Catalogue for July 2007 Item 4 The Arts 3. Veduta Indiana. 1. Zacherias. A.Basoli inv e dip. G.Sandri dis. L. e F. Basoli inc. MA Bonaroti Inve. Piroli f. [n.d., c.1810.] Engraving [Italy, 1821.] Sepia aquatint with line. 295 x 390mm, in brown ink, 370 x 260mm. 14½ x 10¼". £130 11¾ x 15¼". £160 The Old Testament Prophet Zechariah, after the fresco The exterior of an Indian fort. One of three designs by by Michelangelo (1475 - 1564) on the ceiling of the Antonio Basoli for the 1813 production of Gioja's Sistine Chapel. ballet, 'Riti Indiani', published in Basoli's 'Collezione di Engraved by Tommaso Piroli (1752 - 1824) in Rome, varie scene teatrali', 1821. probably from a folio of Michelangelo's designs. Stock: 11607 Stock: 11684 4. Drury Lane Christmas Pantomime. 2. [Man tuning a lute while a woman leafs Hop O' My Thumb. through a song book; three other figures.] [n.d., c.1911?] Ink and watrecolour. Sheet 360 x Wateaux P. N Parr f.(?) [n.d., c.1750.] Etching, 90 x 250mm, 14 x 10". £240 100mm. 3½ x 4". Slightly foxed. £75 A painted playbill for a pantomime version of 'Le Petit A familiar theme of figures playing music and singing Poucet', a fairy tale by Charles Perrault (1628-1703). after Antoine Watteau (1684 - 1721). It appears that There were productions at Drury Lane in 1864, 1892 & Nathaniel Parr (1739 - 1751; active), the London 1911. -

Authenticity, Expertise, Scholarship and Politics: Conflicting Goals in Romani Studies

AUTHENTICITY, EXPERTISE, SCHOLARSHIP AND POLITICS: CONFLICTING GOALS IN ROMANI STUDIES Thomas Acton, Professor of Romani Studies, School of Social Sciences, University of Greenwich Introduction Even though I am now a professor, I have decided to leave my driving licence in the name of "Dr Acton". If you arrive at an eviction, or want to stand bail for someone, as more and more people are being locked up for the offence of being foreigners, then I have found that "Dr" goes down very well with the police where "Professor" would be merely puzzling. Provided I am respectably dressed and nicely spoken, they treat a doctorate not as an achievement which they have to scrutinise, but as an ascribed status, which they can respect without thinking twice. Expertise is also such a status. As an expert witness in court cases, I am not required, as I would have to in an academic paper, to make out an evidential case. Rather, I establish my credentials (so many years of study, so many publications) and then offer my opinion, which then, in itself, coming from an expert, becomes evidence. The substance of my opinion will be disputed only if there is also an expert on the other side; and even then the contest will be more of eloquence than of science. So I go to planning cases, and offer my opinion that various appellants against refusal of planning permission for caravan sites are indeed Gypsies, and therefore entitled to Gypsy status under planning law. It is not enough for a Gypsy to say he is a Gypsy in court; it takes a non-Gypsy professor like me to say it convincingly. -

Who Owned Waterloo? Complete Bibliography ©Luke Reynolds, 2020 Complete Bibliography Archives Bodleian Librar

Luke Reynolds – Who Owned Waterloo? complete Bibliography ©Luke Reynolds, 2020 Complete Bibliography Archives Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK British Library, London, UK Hartley Library, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK Kent Archives Office, Kent, UK Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada National Archives, Kew, UK National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK Royal Academy Archive, Royal Academy, London, UK. McGill University Library, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Stratfield Saye House Archive, Stratfield Saye, Hampshire, UK Tate Britain, London, UK Templer Study Centre, National Army Museum, London, UK Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK Toronto Reference Library, Toronto, Canada University Library, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, USA Museums Apsley House, London, UK. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. The British Museum, London, UK. Harewood House, Leeds, UK. National Army Museum, London, UK People’s History Museum, Manchester, UK The Royal Collection Trust, Windsor Castle Luke Reynolds – Who Owned Waterloo? complete Bibliography ©Luke Reynolds, 2020 Surgeons’ Hall Museums, Edinburgh, UK Tate Research Groups, Tate Britain, London, UK Databases 200 Objects of Waterloo, Waterloo 200 Art UK Australian Dictionary of Biography Dictionary of Canadian Biography Grove Art Online Hansard Historic Hansard Measuring Worth Oxford Dictionary of National Bibliography Statistics