Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Thesis.Pdf (PDF, 297.83KB)

Cover Illustrations by the Author after two drawings by François Boucher. i Contents Note on Dates iii. Introduction 1. Chapter I - The Coming of the Dutchman: Prior’s Diplomatic Apprenticeship 7. Chapter II - ‘Mat’s Peace’, the betrayal of the Dutch, and the French friendship 17. Chapter III - The Treaty of Commerce and the Empire of Trade 33. Chapter IV - Matt, Harry, and the Idea of a Patriot King 47. Conclusion - ‘Britannia Rules the Waves’ – A seventy-year legacy 63. Bibliography 67. ii Note on Dates: The dates used in the following are those given in the sources from which each particular reference comes, and do not make any attempt to standardize on the basis of either the Old or New System. It should also be noted that whilst Englishmen used the Old System at home, it was common (and Matthew Prior is no exception) for them to use the New System when on the Continent. iii Introduction It is often the way with historical memory that the man seen by his contemporaries as an important powerbroker is remembered by posterity as little more than a minor figure. As is the case with many men of the late-Seventeenth- and early-Eighteenth-Centuries, Matthew Prior’s (1664-1721) is hardly a household name any longer. Yet in the minds of his contemporaries and in the political life of his country even after his death his importance was, and is, very clear. Since then he has been the subject of three full-length biographies, published in 1914, 1921, and 1939, all now out of print.1 Although of low birth Prior managed to attract the attention of wealthy patrons in both literary and diplomatic circles and was, despite his humble station, blessed with an education that was to be the foundation of his later success. -

The Seaxe Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society

The Seaxe Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society Editor – Stephen Kibbey, 3 Cleveland Court, Kent Avenue, Ealing, London, W13 8BJ (Telephone: 020 8998 5580 – e-mail: [email protected]) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… No.56 Founded 1976 September 2009 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Queen Charlotte’s Hatchment returns to Kew. Photo: S. Kibbey Peach Froggatt and the restored Queen Charlotte‟s Hatchment in Kew Palace. Late afternoon on Thursday 23rd July 2009 a small drinks party was held at Kew Palace in honour of Peach Froggatt, one of our longest serving members. As described below in Peach‟s own words, the hatchment for Queen Charlotte, King George III‟s wife, was rescued from a skip after being thrown out by the vicar of St Anne‟s Church on Kew Green during renovation works. Today it is back in the house where 191 years ago it was hung out on the front elevation to tell all visitors that the house was in mourning. “One pleasant summer afternoon in 1982 when we were recording the “Funeral Hatchments” for Peter Summers “Hatchments in Britain Series” we arrived at Kew Church, it was our last church for the day. The church was open and ladies of the parish were busy polishing and arranging flowers, and after introducing ourselves we settled down to our task. Later the lady in charge said she had to keep an appointment so would we lock up and put the keys through her letterbox. After much checking and photographing we made a thorough search of the church as two of the large hatchments were missing. Not having any luck we locked the church and I left my husband relaxing on a seat on Kew Green while I returned the keys. -

Property from the Portland Collection at Christie's In

For Immediate Release Monday, 8 November 2010 Press Contact: Hannah Schmidt +44 (0) 207 389 2964 [email protected] Matthew Paton +44 (0) 207 389 2965 [email protected] PROPERTY FROM THE PORTLAND COLLECTION AT CHRISTIE’S IN NOVEMBER & DECEMBER Magnificent Jewels, Fabergé, Old Masters and Sculpture The Duchess of Portland in The Combat between Carnival and Lent by Pieter Brueghel II coronation robes, 1902 (Brussels 1564- 1637/8 Antwerp) © gettyimages: Hulton Archive Estimate: £2,000,000–3,000,000 London – Christie’s announce an historic opportunity for connoisseurs around the globe in late November and early December, when a magnificent selection of jewellery, Fabergé, old master paintings and sculpture will be offered from collections of the Dukes of Portland, in a series of auctions in London. 22 lots will be showcased in four auctions over two weeks: Russian Art on Tuesday 29 November; Jewels: The London Sale on Wednesday 1st December; Old Masters & 19th Century Art on Tuesday 7th and 500 Years: Decorative Arts Europe on Thursday 9th. Highlights are led by the re-appearance of The Combat between Carnival and Lent by Pieter Brueghel II (Brussels 1564-1637/8 Antwerp) (estimate: £2,000,000– 3,000,000), illustrated above, a sumptuous antique diamond and natural pearl brooch, with three drops, 1870 (estimate: £500,000-700,000) and an exceptionally rare terracotta bust of John Locke, 1755, by Michael Rysbrack (1694-1770) (estimate: £600,000-900,000). With estimates ranging from £4,000 to £3 million, Property from The Portland Collection is expected to realise in excess of £6 million. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

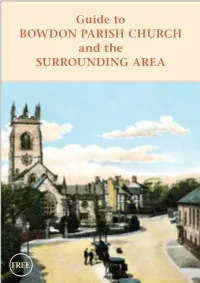

Guide to BOWDON PARISH CHURCH and the SURROUNDING AREA

Guide to BOWDON PARISH CHURCH and the SURROUNDING AREA FREE i An Ancient Church and Parish Welcome to Bowdon and the Parish The long ridge of Bowdon Hill is crossed by the Roman road of Watling Street, now forming some of the A56 which links Cheshire and Lancashire. Church of St Mary the Virgin Just off this route in the raised centre of Bowdon, a landmark church seen from many miles around has stood since Saxon times. In 669, Church reformer Archbishop Theodore divided the region of Mercia into dioceses and created parishes. It is likely that Bowdon An Ancient Church and Parish 1 was one of the first, with a small community here since at least the th The Church Guide 6 7 century. The 1086 Domesday Book tells us that at the time a mill, church and parish priest were at Bogedone (bow-shaped ‘dun’ or hill). Exterior of the Church 23 It was held by a Norman officer, the first Hamon de Massey. The church The Surrounding Area 25 was rebuilt in stone around 1100 in Norman style then again in around 1320 during the reign of Edward II, when a tower was added, along with a new nave and a south aisle. The old church became in part the north aisle. In 1510 at the time of Henry VIII it was partially rebuilt, but the work was not completed. Old Bowdon church with its squat tower and early 19th century rural setting. 1 In 1541 at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the parish was transferred to the Diocese of Chester from the Priory of Birkenhead, which had been founded by local lord Hamon de Massey, 3rd Baron of Dunham. -

Keeping up with the Dutch Internal Colonization and Rural Reform in Germany, 1800–1914

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 Keeping Up with the Dutch Internal Colonization and Rural Reform in Germany, 1800–1914 Elizabeth B. Jones HCM 3 (2): 173–194 http://doi.org/10.18352/hcm.482 Abstract Recent research on internal colonization in Imperial Germany empha- sizes how racial and environmental chauvinism drove plans for agri- cultural settlement in the ‘polonized’ German East. Yet policymakers’ dismay over earlier endeavours on the peat bogs of northwest Germany and their admiration for Dutch achievements was a constant refrain. This article traces the heterogeneous Dutch influences on German internal colonization between 1790 and 1914 and the mixed results of Germans efforts to adapt Dutch models of wasteland colonization. Indeed, despite rising German influence in transnational debates over European internal colonization, derogatory comparisons between medi- ocre German ventures and the unrelenting progress of the Dutch per- sisted. Thus, the example of northwest Germany highlights how mount- ing anxieties about ‘backwardness’ continued to mold the enterprise in the modern era and challenges the notion that the profound German influences on the Netherlands had no analog in the other direction. Keywords: agriculture, Germany, internal colonization, improvement, Netherlands Introduction Radical German nationalist Alfred Hugenberg launched his political career in the 1890s as an official with the Royal Prussian Colonization Commission.1 Created by Bismarck in 1886, the Commission’s charge HCM 2015, VOL. 3, no. 2 173 © ELIZABETH B. -

0 Frances Duchess of Richmond and Lenox Robertson

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ERANCES, DUCHESS OE RICHMOND AND LENOX. 225 FEANCES, DUCHESS OF EICHMOND AND LENOX FRANCES, Duchess of Richmond and Lenox, a daughter of Thomas Howard, Viscount Bindon, was through her grand- mother Lady Elizabeth Stafford (wife of the third Duke of Norfolk) a scion of that great ducal family of Buckingham, which had owned the Manors and Parks of Tunbridge and Penshurst, with vast possessions in Kent. She had a threefold connection with Cobham. William Brooke Lord Cobham married Dorothy Nevill, who was the first cousin of her father Viscount Bindon. Henry Brooke Lord Cobham married Frances Countess of Kildare, who was her own second cousin. She herself married (as her third husband) Ludovic Stuart, Duke of Lenox, to whom his second cousin, King James I, had granted a large portion of Lord Cobham's forfeited estates. When the Duke died, 16 February, 162|, and was succeeded, as third Duke of Lenox, by his brother Esme, the Duchess Frances asserted her claim to a widow's legal "thirds," of Cobham, and of the other Lenox estates, but only for the purpose of handing them over as a gift to her brother-in-law. The list of such things as she thus gave to him is interesting, and will be found in a foot note* below. He did not succeed to * Domcstio State Papers, James I, vol. clxxi, No. 87. A note of such things as my Lady the Duches of Richmond gave to her brother the late Duke of Lenox & his Heire the Lord Darnly which were hers by Lawe being Moveables, but shee gave them freely to him, for the Mainte- nance of him & the Howse of Lenox after him Out of her Dutie to her deceased Lord and her Love & Care of the Howse of Lenox, viz.: Imprimis the proflittes of the Patents of the Olnage after seauen yeares after which time there wilbe fEorty twoe yeares to come: Her Grace hath fioure and twentie hundred pounds by the yeare for it nowe, the Kings Bent being paid : But afterwards yt wilbee a great deale more. -

The Grand Duchy of Warsaw

Y~r a n c v s> Tne Grand Duch} Of Warsaw THE GRAND DUCHY OF WARSAW BY HELEN ELIZABETH FKANCIS THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS Oo CM Z? 191 6 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY 1 ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Jiistru^ySr in Charge APPROVED: ^f^r^O /<a%*££*^+. 343G60 CONTENTS I. Short Sketch of Polish History before the Grand Duchy of Warsaw 1 II. The Establishment of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw 20 III. The Grand Duchy of Warsaw from 1807—1812 37 IV. The Breach of 1812 53 V. The Fate of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw as Decided at 74 the Congress of Vienna, 1815 VI. The Poles Since 1815 84 VII. Bibliography A. Primary Material 88 B. Secondary Material 91 C. Bibliographical Notes 95 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/grandduchyofwarsOOfran 1. I. A Short Sketch of Polish History before THE br&AftU UUUHi UP WAHSAW Among the many problems which demand the attention of the world today is that of Poland, and the outbreak of the ^reat War now going on in Europe has made this problem prominent. Ever since the final partition in 1795, the patriotic poles have held closely in their hearts the idea of a reunited independent country. Uprisings in Russian Poland in 1831, 1 in ualicia in 2 3 1855, and in Russia in 1863 showed that these ideas were alive. -

Stuttgarter Antiquariatsmesse

KATALOG CCXXX 2021 NEUZUGÄNGE ZUR (VIRTUELLEN) STUTTGARTER ANTIQUARIATSMESSE ANTIQUARIAT CLEMENS PAULUSCH GmbH ANTIQUARIAT NIKOLAUS STRUCK VORWORT INHALT Liebe Kunden, Kollegen und Freunde, Aus dem Messekatalog 1 - 12 Stadtansichten 13 - 303 das Jahr 2021 beginnt wie kaum ein anderes in der jüngeren Geschichte. Landkarten 304 - 528 Wir hätten uns vor 12 Monaten nicht vorstellen können, dass die Dekorative Grafik 529 - 600 Stuttgarter Antiquariatsmesse – wie viele andere Messen auch – ausfällt und nur mit einem gedruckten Katalog und virtuell stattfindet. Wir hätten uns aber vor einem Jahr so vieles nicht vorstellen, was in den vergangenen Monaten traurige Realität wurde. Wir werden Ihnen demnach in diesem Jahr keine Auswahl an Stadtan- sichten und Landkarten im Württembergischen Kunstverein präsentieren Allgemeine Geschäfts- und können, möchten aber wie auch in den vergangenen Jahren mit einem Lieferbedingungen sowie die Katalog die letzten Neuzugänge vorstellen. Im Gegensatz zu den vergan- Widerrufsbelehrung finden Sie genen Jahren sind ausnahmslos alle Titel des Kataloges sofort bestell- auf der letzten Seite. bar, auch die ersten zwölf, die Bestandteil des gedruckten Katalogs sind. Den Messekatalog können Sie auf der Homepage der Messe herunter- laden (https://www.antiquariatsmesse-stuttgart.de/de/katalog/katalog- Lieferbare Kataloge als-pdf) und können ihn auch über den Verband Deutscher Antiquare beziehen. Katalog 222 665 Karten und ein Atlas (666 Nummern) Da wohl bis auf weiteres der persönliche Kontakt mit Ihnen unterbleiben muss, wünschen wir Ihnen auf diesem Wege das Beste für 2021. Katalog 226 Unser Ladengeschäft ist derzeit geschlossen, Besuche sind aber nach Deutschland Teil 7: Nachträge persönlicher Vereinbarung in Ausnahmefällen möglich. Wir sind per Mail (1000 Nummern) und während der üblichen Öffnungszeiten (außer Samstags) auch telefonisch erreichbar. -

Hawstead Hatchments 2Page Handout.Pdf

1 2 3 4 5 The Hawstead Hatchments from Left to Right 1. FRANCES Jane Metcalfe, died 1830 aged 36. Frances was the first wife of Henry Metcalfe of Hawstead House (his hatchment is no. 4). On the shield, his ‘arms’ are on the left and the background is white, indicating that he is still alive. This contrasts with the right side of the hatchment (his wife’s side) which is black. The coat of arms on her side is that of her ancestral family which is Whish. NB “Resurgam” = “I shall arise again”. 2. SOPHIA Metcalfe, died 1855 aged 66 OR ELLEN Frances Metcalfe, died 1858, aged 70. It is unclear which of these two unmarried sisters of Henry Metcalfe this hatchment commemorates. The absence of the heraldic shield and helmet and the presence of a ribbon at the top, together with the completely black background, indicate that this hatchment is for a deceased spinster. 3. FRANCIS Hammond, died 1727, aged 38. This is the oldest hatchment, and the only one not commemorating a member of the Metcalfe family. The Hammonds lived at “Hammonds” in Bull Lane, Pinford End (a hamlet within Hawstead). Francis was married to Honor Asty and hence his coat of arms, including the birds and a chevron with scallops, is on the left with the Asty arms, two falcons and a diagonal stripe of ermine on a red background, to the right. The fact that the background is completely black indicates that the hatchment was made in 1758 after she died. NB “Mors janum vitae” = “Death is the doorway to life”. -

Hardinge Giffard, 1St Earl of Halsbury, Lord High Chancellor

st Hardinge Giffard, 1 Earl of Halsbury, Lord High Chancellor Background History Born in London, you are the third son of Stanley Lees Giffard, editor of the Standard newspaper, by his wife Susanna, daughter of Francis Moran. You were educated at Merton College, Oxford, and called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1850.’ You quickly became important within the circuit and went on to have a large practice at the central criminal court and the Middlesex sessions. You even served for several years as the junior prosecuting counsel to the Treasury. You then became Queen's Counsel in 1865 and a bencher of the Inner Temple. As you continued on with your efforts in the legal world you made yourself quite the name in the United Kingdom. You won a great many high profile cases surrounding fraud in the budget and also represented high profile clients in a number of suits against factories for child labor and suits for workers rights. This has made you a hero of the people in many places in the Midlands and in South Wales, where many of the workers benefited from your victories. While you were acting as a barrister, you also began to garner an interest in politics. Using the political capital you had amassed from your legal work both politically and popularly, you tried to enter into the House of Commons. However, ultimately you remained without a seat in the House of Commons, even when appointed to be the Solicitor General by Disraeli in 1875. While in this position you acted as an invaluable font of legal information for the crown, helping provide them legal guidance in the face of rapidly changing laws around workers rights, social norms, and also industrial practices.